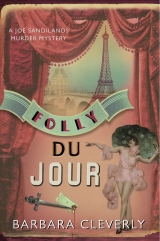

Текст книги "Folly Du Jour"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Chapter Seven

Joe had been aware for some time that shame had been doing battle with disciplined deference in his friend. But the young Inspector was a Burgundian by birth and possessing the Burgundian traits almost to the point of caricature. Merry, deep-drinking, wily and – above all – proud.

Bonnefoye stalked to the desk, seized the Perrier bottle by its elegant neck and proceeded to fill the water glass with the deft movements of a waiter. ‘The Crillon it clearly is not,’ he said affably, ‘nor yet is it the Black Hole of Calcutta.’

He presented the glass to George and watched him empty it with one draught, bubbles and all. George handed it back with an appreciative belch.

‘Eternally grateful, young man.’

‘George, this is my colleague Jean-Philippe Bonnefoye. Inspector Bonnefoye,’ said Joe. ‘Though not for much longer,’ he added to himself with an eye on Fourier. Expressionless, the Chief Inspector had unscrewed the cap of his fountain pen and was making a note on a pad at his elbow.

Was recklessness a Burgundian characteristic? Or was it Gascon? Joe wondered. Whichever it might be, Bonnefoye was demonstrating it with relish. His next act of defiance was to reach over and ring the bell. The sergeant came in at once. ‘We need some chairs in here. Fetch three,’ said Bonnefoye.

‘Yes, sir,’ muttered the sergeant. He looked sideways for a countermanding order, but, receiving none, bustled out.

Another note was scratched on the pad. Fourier’s mouth twisted into an unpleasant grimace which Joe was alarmed to interpret as a smile.

A moment later three stacked chairs made their appearance and Joe and Bonnefoye took delivery, lowering Sir George with creaks and groans down on to one of them. They seated themselves one on each side of him, protective angels. Joe sighed. He feared Fourier’s pad was going to be overflowing with damning comments before the hour was up. He exchanged a grin with Bonnefoye. Ah well . . . in for a penny . . .

‘And now, Fourier, if you wouldn’t mind – your procès verbal. How’s it coming along? The sooner his statement’s in, the sooner we can get it to the clerk’s office . . . le greffe? Is that what you’d say? And then we can all get out of your hair and you can get back to the business of arresting someone for the killing in the theatre.’

‘I have him. The killer sits between you,’ said Fourier in a chilling tone. ‘Here’s what Jardine has confided. Here – why don’t you take it. Read it. Come to your own conclusions.’

Joe was alarmed to hear the certainty verging on gloating in his voice. He took the meagre account, amounting to no more than two sheets of paper, and began to read. He was quick to pass the report to Bonnefoye who ran through it and looked up, disturbed.

‘Sir George,’ Joe began, ‘I’d like you to go through this with me, confirming, if you would, that the Chief Inspector has not misinterpreted anything you had to say. Adding anything you feel has been overlooked. Bonnefoye and I between us ought to be able to hack together something solid. Now . . . you detail your reason for attending this particular performance . . . The gift of a ticket, you say?’

‘Not actually a ticket,’ corrected George, opening in the voice of the meticulous witness, ‘one of those annoying tokens they issue. A sort of ticket for a ticket – you cash the first one in for the real thing when you get to the theatre. It’s a ridiculous system for extracting more francs from –’

‘Sent to you by a cousin, you say?’ Joe set him back on course.

‘No, I don’t say. Not for certain. I kept the note that came with the token. Fourier has it,’ he said.

Fourier passed over a torn envelope and a short note.

‘John? Just “John”? Could be anyone, surely? Does this help?’ Joe asked.

‘No help at all. I must know about two dozen Johns and most of them likely to be passing through Paris sometime during the year. I took it to be my young cousin John who’s posted to the Embassy here though I didn’t at first catch on – always call him Jack, you see. These people,’ George waved a gracious hand in the direction of the Chief Inspector, ‘allowed me a phone call at least though they insisted on doing it for me. They got hold of him at the Embassy and I’d guess it’s due to his efforts on my behalf that you’re here, Commander.’

‘You may also wish to see this,’ smiled Fourier. He passed over a scrawled report on a sheet of Police Judiciaire writing paper. ‘I sent out an officer to interview the gentleman, of course.’

Joe summarized the statement, reading aloud: ‘“Confirm Sir George Jardine my cousin . . . no knowledge of any gift of theatre tickets. Didn’t even know he was in Paris.” Ah. Some mystery there, then. Well, moving on: you arrived at the theatre –’

‘Where he was ambushed by a second mystery,’ Fourier interrupted. ‘Are you now, in this welcome rush of revelation, going to disclose the identity of the lady who joined you in your box, monsieur?’

Enjoying Joe’s surprise, he added, ‘The ouvreuse in attendance on the boxes yesterday evening is a lively young woman and very alert. She it was who discovered your friend in the act of slitting his compatriot’s throat. She identified him as the gentleman from Box A across the theatre. She was able to tell us that, moments before the performance started, monsieur was joined by a woman. A Frenchwoman, she thought, from their brief conversation, and wearing an opera cape. The hood was up and she would be unable to identify her or indeed, remember her face. From the closeness of the chairs in that box, when I examined it, the two knew each other well, I’d say. Or at least were friendly. The bar reveals that both occupants drank a glass of whisky in the interval. And – I would ask you to note – the drinks order was placed before the lady arrived. She was clearly expected. By Sir George.’

‘George? This is nothing but good news! If we can find this lady, she will provide your alibi, surely? Who on earth was she?’

‘No idea! She just turned up moments before the performance started.’ George’s mystification was evident. ‘A lady of the night, I assumed. Well – wouldn’t you? Most probably a gesture from the magnanimous John. Whoever he is. Can’t say I approve much of such goings-on! I say – is this sort of behaviour becoming acceptable in Paris these days? The done thing, would you say?’

His words ran into the sand of their silent speculation. Joe paused to allow him to expand on his statement but George appeared unwilling.

He pressed on. ‘You were not able to furnish the Chief Inspector with a description of the lady?’

‘Sadly no. She was wearing one of those fashionable cape things . . . Kept it on over her head. She came in after the lights went out . . .’

‘The lights went on during the interval?’ Joe objected quietly. He was beginning to understand some of Fourier’s frustration.

‘Jolly awkward! I mean – what is one to say in the circumstances? Any out and out dismissal or rejection is bound to give offence, don’t you know! I chatted about this and that – put her at her ease. She didn’t have much to say for herself . . . comments on the performance . . . the new look of the theatre, that sort of thing. I gave her a glass of the whisky I’d ordered in expectation of a visit from my cousin Jack who’s very partial to a single malt –’

‘The lady,’ said Joe. ‘What do you have to report?’

‘Um . . . didn’t like the scotch but too polite to refuse. She’d probably have preferred a Campari-soda . . . I think you know the type . . .’ He paused. His mild blue eye skittered over Joe’s and then he drawled on: ‘French. Yes, I’m sure she was French. Spoke the language like a native, I’d say. Though I’m not the best judge of accents. Not perhaps a Parisian,’ he added thoughtfully. ‘Cape all-enveloping, as I’ve said, no clear idea of her features. But – average height for a woman. Five foot something . . .’ He caught Joe’s narrowed look and amplified: ‘Five foot five. Slim. Well-educated. Obviously from a top-flight establishment. Suggest you start looking there. I expect the Chief Inspector is well acquainted with these places? In the line of professional enquiry, of course.’

Joe hurried on. ‘Moving to the finale . . . You say there was a commotion when Miss Baker announced the arrival of the Spirit of St Louis . . .’

‘Commotion? It was a standing ovation! Went on for at least ten minutes. Stamping, shouting and yelling! Quite unnecessary and embarrassing display! And that’s when she disappeared, I think. My unknown and unwanted companion.’

‘And at the true finale – Golden Fountain, you call it? – you observed your acquaintance Somerton to be slumped in his box opposite.’

‘I feared the worst. Well, not the worst I could have feared, not by a long chalk, as it turned out . . . Thought he’d had a heart attack. Anno domini, don’t you know . . . Stimulating show and he’d been twining about a blonde of his own . . .’ George bit his lip at his faux pas, hearing it picked up in the energetic scratching of Fourier’s pen, but he ploughed on: ‘A spectacular girl – I’ve given the description.’

‘Yes, I see it. Remarkably detailed, Sir George. She obviously made quite an impression?’

‘The girl thirty metres away was clearly more vivid to Jardine than the one who was practically sitting in his lap,’ offered the Chief Inspector acidly.

‘Opera glasses, George? . . . Yes, of course.’

‘And she disappeared from her box . . . oh, no idea, really,’ said Sir George vaguely. ‘Sometime before the finale, that’s as near as I can say.’

‘And you decided to go over there in a public-spirited way to see if you could render assistance?’

‘Old habits die hard, you know. Taking charge of potentially awkward situations . . . always done it . . . always will, I expect. Interfering old nuisance, some might say.’

‘Sir George has run India for the last decade,’ Joe confided grandly, probably annoying the hell out of Fourier, he thought, but he pressed on: ‘Riots, insurgencies, massacres . . . all kinds of mayhem have been averted by his timely intervention. Adisturbance in a theatre box is something that would elicit energetic action.’

‘As would intent to murder,’ replied the Chief Inspector, unimpressed.

‘Tell us what happened next, will you? I see that this is as far as you got in twelve hours, despite vigorous encouragement from the Chief Inspector. No wonder he’s looking a bit green around the gills.’

George described with accompanying gestures the scene of discovery. The Chief Inspector scribbled.

At last when George fell silent, Fourier put down his pen, a look of triumph rippling across his features. ‘And this story meshes splendidly with the eyewitness account we are given by the helpful ouvreuse, but only up to a point.’

With a generous gesture, he peeled off another police witness sheet and allowed Joe and Bonnefoye to read it.

‘The lady says . . . I say, shall we call her by her name since she seems to be playing rather more than a walk-on role in this performance? Mademoiselle Francine Raissac states that she came upon the two Englishmen in Box B in the course of her nightly clearing-up duties. The man she refers to as “the ten franc tip” – the large good-looking one (Sir George) – was in close contact with the smaller weaselly one (“the five franc tip”) and she took the former to be in the act of cutting the throat of the latter since the blood was flowing freely between the two and Sir George, who turned and looked up on hearing her scream, was covered in his compatriot’s blood.

‘The men were alone in the box, the partner of the five franc tip being no longer present. Mademoiselle Raissac declares she is unable to furnish us with a full description of the lady. She had never seen her before. She remembers she was young – less than twenty-five years old – and had fair hair. Mademoiselle Raissac further declares the girl must have been speaking French since she (Mademoiselle Raissac) was not conscious of any accent. Mmm . . .’

‘A second elusive fair beauty. How they cluster around you Englishmen! I do wonder what the attraction is,’ scoffed Fourier.

As George seemed to be about to tell him, Joe changed the subject with a warning scowl. ‘I should very much like to see the corpse,’ he said, ‘and hear the opinion of your pathologist . . .’

‘But certainly,’ agreed the Chief Inspector. ‘And perhaps you would also like to examine the murder weapon? Oh, yes, it was discovered. At the feet of the corpse on the floor of the box where Sir George dropped it. A finely crafted Afghani dagger.’ He turned and looked for the first time at George. ‘I understand, Jardine, that you were, at one time, a soldier in Afghanistan?’

‘A long time ago,’ said George. ‘As was Somerton. We both served for a spell on the North-West Frontier. The blade was most probably his own. He had a fondness for knives. And a certain skill with them. It definitely wasn’t mine. I have an abiding aversion for them. I favour a Luger these days for self-protection. Though I make a point of never going armed to the theatre. Too tempting to express an over-critical view of the performance. And these closely tailored evening suits – anything more substantial than a hatpin completely ruins the line, you know.’

Joe was reassured to hear a flash of the old Sir George but was becoming more anxious for his safety as the sorry tale evolved. His old friend, the man he admired and trusted above all others, was in serious trouble.

Fourier clearly didn’t believe a word he said and was looking out for a quick arrest. Possibly within the twenty-four-hour limit he prided himself on achieving. If George had killed this man, Joe was quite certain Somerton had deserved it. But he determined to know the truth. His compulsion was always to go after the truth using any means at his disposal; he had no other way of functioning. And having found out the truth? And supposing it didn’t appeal to him? He smiled, recalling the wise words of an old member of the Anglo-Indian establishment . . . what had been her name? . . . Kitty, that was it. Mrs Kitson-Masters.

‘What could be more important than the truth?’ he’d asked her one day some years ago in Panikhat, at a moment when he was being, he remembered, particularly officious, annoyingly self-righteous. And, gently, she’d replied: ‘I’ll tell you what: the living. They’re more important than the dead and more important than the truth.’ And, as long as George was among the living, Joe would lay out all his energy and skill to keep him there.

But there was bargaining to be done. Agreement to be reached. Feathers to be smoothed and arms to be twisted. Joe grinned. He was going to have to discount the pathetic and confused old person sitting next to him and call on all the skills he’d learned from the man he’d first met as Sir George Jardine, Governor of Bengal, Adviser to Viceroys and discreet Spymaster of India.

And the first of these skills had been: never to lose your temper, and the second: to deploy what Joe had always thought of as a type of mental ju-jitsu. Identify and assess your opponent’s strength and, under the guise of accommodation and reason, use its energy against him to propel him arse over tip on to the nearest dung-heap.

He turned a tentative smile of relief on Fourier when he looked up from the notes which were now flowing fast from his pen.

‘I’d say this is going rather well, wouldn’t you, Fourier? But if you’re thinking the magistrate is not going to be happy to accept so much conflicting and inconclusive evidence without the underpinning surety of a confession – well, then, I’d be the first to agree with you.’

Fourier scowled at him suspiciously.

Joe leaned forward in his chair, hands on his knees, fixing his opposite number with a keen stare. He spoke to him with quiet force. They could have been the only two people in the room. ‘I’m an ambitious man, Chief Inspector,’ he confided. ‘You’ve seen my card. You are aware of how I am currently . . . placed –’

‘Poised, I’d have said,’ interrupted Fourier.

Joe smiled. ‘As you say – “poised” will do very well . . . poised for advancement. I make no secret of the fact that I have my eye on the directorship of one of the more interesting divisions at the Yard. “Assistant Commissioner” would not be out of the question. There is much competition, many excellent candidates. Not a few are military men who know how to plan an effective campaign. I expect it’s the same over here? And it’s the man who can forge a reputation for himself who will win out. The one who can make himself stand out from the rest. “Ah, yes – Sandilands. Isn’t he the bloke who cleared up that killing in Paris?” I believe I have a nose for an interesting, attention-grabbing case. And we have one here!’ He paused for a moment to allow his excitement to be caught on the other side of the desk.

Fourier yawned.

‘A front-page, sell-every-copy story that could rival the Whitechapel murders. On both sides of the Channel. It has everything one could ask for! Pretty girls, daggers, gallons of blood spilt in the most spectacular of settings . . . And – cherry on the cake – the victim is a rosbif – an Englishman for whom we need feel no sympathy. Probably got no more than he deserved . . . I challenge you to invent three possible headlines for this case. Go on, man!’

Joe took out his notebook and pencil and began to scribble. Before Fourier had a chance to call a halt to his games, he rushed on. ‘Got it! I’ve got one for the English press. Not sure that it will do much for you. You’ll have to invent your own. Death du Jour,’ said Joe. ‘What do you say?’

‘Not bad. I’d use something a bit longer and more dramatic – that’s the style of our papers. They like to involve a famous person: Did the Black Venus witness the Angel of Death? They’re bound to pick up the fact that the star of the show could well have been onstage at the very moment when Jardine struck the blow – only a few feet away as it happens,’ Fourier speculated.

George tensed, preparing to object, but stayed silent, aware of Joe’s tactics.

‘They might use Throat-slashing at the Folies . . .’ Fourier went on with ready invention and it occurred to Joe that his mind had already been running in just such a direction. He wondered if George, his mentor, had seen it? Joe had rightly guessed the Chief Inspector’s imperative, his motivation. He’d judged Fourier’s craving for advancement to be at the same time his strength and his weakness and, by ascribing the same ruthless ambition to himself, Joe had made it appear acceptable in his eyes. More than acceptable – commendable. He had bracketed them together, two like-minded cynics ready to exploit a situation for their mutual benefit. Somerton, Sir George, even Bonnefoye were marionettes, their strings in the hands of two hard-eyed professionals.

Joe wasn’t quite there yet but he was on his way to using the power of Fourier’s forward rush to kick him into space.

‘Two Englishmen fight to the death for the favours of a mysterious fille de joie. Plea for the blonde beauty to come forward.’ The Chief Inspector was enjoying himself. He shrugged. ‘Well, these news editors – they’ll say whatever they like. Of course, sometimes they respond to a confidential suggestion in their ear.’

He looked at the clock and glared at Sir George. The obstacle between him and his story. ‘Pour the man another glass of water, Bonnefoye,’ he said. ‘It seems to loosen his tongue.’

‘Fourier, may I have a word in private?’ Joe asked.

He left the room with the Chief Inspector, a companionable hand on his shoulder. They returned a minute or two later and Joe went to stand almost to attention by Fourier’s desk, alongside him and facing the other two men.

Fourier cleared his throat and gathered up his documents. ‘Gentlemen,’ he said, ‘the Commander and I have come to a decision. In order to pursue the case further, I will be releasing the prisoner from police custody into police custody. Jardine is to be handed over to Sandilands with the assurance that he will not attempt to leave the city. I retain his passport and his documents. I require him to attend for a further interview as and when I deem it necessary.’

He rang the bell. ‘Sergeant – the prisoner’s clothes are to be kept as evidence. Can you find an old mackintosh or something to cover the mess? And you may bring his shoelaces and braces back. Gentlemen – go with the sergeant. He will walk you through the process of signing out the prisoner. Oh, and Commander – your request to examine the corpse – I grant this and will leave instructions at the morgue accordingly. Now – Bonnefoye! I’m not au fait with your schedule . . . Remind me, will you?’

‘Mixed bag, sir. The suspected poisoning in Neuilly – toxicology report still awaited. The body under the Métro train – no ID as yet. And there’s last night’s floating bonne bouche dragged from the St Martin . . . And the conference, of course.’ He smiled blandly back at the Chief Inspector.

‘Then I recommend that you get yourself back on track at once.’ Fourier added with menacing politeness: ‘Your contribution to the proceedings has been noted.’

Joe thanked him and, taking advantage of the spirit of burgeoning co-operation, asked if he might fix a time to escort Lady Somerton to the morgue for purposes of identification. Fourier was beginning to see the advantages of having an Englishman on hand, Joe thought, as his response was quick and positive. His own response would have been the same. The dreadful scene of the widow wailing over the remains was always the one to be avoided, particularly when the grieving was being done in a foreign language. It added an element of awkwardness to a situation requiring sympathy and explanation. Fourier seemed to have no objection to passing on this delicate duty. They eyed each other with a gathering understanding and a mutual satisfaction.

The unanimous verdict burst from the three men as they reached the safety of the courtyard below:

‘Arsehole!’

‘Qu’il est con!’

‘Fuckpot!’

Without further exchange or consultation, they quickly made their way out on to the breezy quayside where George came to a standstill, content to stare at the river traffic, enjoying its bustling ordinariness. He listened to the shouts, the hoots, the throbbing of the engines; he narrowed watering eyes against the brilliance of the spring sunshine dancing on the water. He waved and shouted something teasing at a small terrier standing guard on a passing barge. It barked its defiance. George wuffed back and laughed like a boy in delight. An escaper from one of the circles of hell, Joe judged. A night in clink with Fourier for company would make anyone light-headed.

With something like good humour restored, Joe began to lay out a programme for the rest of the morning. He was interrupted by Sir George. ‘The hotel can wait,’ he declared. ‘Now we’re free of this dreadful place, I want some breakfast! Some of that soup wouldn’t come amiss. Where did you get it?’

Joe eyed his dishevelled state and was doubtful; George was looking even less appetizing in the bright light of morning. He could have strolled over to join the dozen or so tramps just waking under the bridge a few yards away and they’d have shuffled over to make room for a brother. But at least, the worst of the bloodstains were hidden under a dirty old wartime trench coat two sizes too small.

Bonnefoye was more confident. ‘Excellent idea! Looking as you do, we won’t take you to a respectable café. Au Père Tranquille – that’s where we’ll go. Back to the Halles, Joe. It’s a workmen’s café – they’ll just assume Sir George is a tourist who’s fallen foul of some local ruffians. Or an American artist slumming. Wait here by the gate – I’ll flag down a taxi.’

After his second bowl of soup with a glass of cognac on the side, a whole baguette and a pot or two of coffee, George’s colour was returning and his one good eye had acquired a sparkle.

‘I’m curious! Are you going to tell us, Joe,’ Bonnefoye asked, ‘what precisely you said to the Chief Inspector that made him change his mind? Rather a volte-face, wasn’t it? I could have sworn he was all set to have another go at harrying Sir George. Perhaps closing his other eye?’

‘No, no! You’re mistaken, young man,’ said George. ‘I tripped and banged my head against a corner of the desk. But – you’re right – I have a feeling I was about to execute the same tricky manoeuvre on the other side. What did you say, Joe, to turn him through a hundred and eighty degrees?’

Joe stared into his coffee cup. ‘I merely suggested that if Fourier had it in mind to apply the thumbscrews, he might like to know that Sir George had been for years a soldier in the British forces, battling the bloodthirsty Afridi to say nothing of Waziri tribesmen in the wilderness west of Peshawar. I enquired whether he was aware that George had at one time been captured by the enemy and subjected to torture of an inventive viciousness of which only the Wazirs are capable. Rescued in the nick of time, more dead than alive after three days in their hands, but having divulged no information to his captors. Not a word. Name, rank and number and that’s it. Surely Fourier, during his physical inspection of his prisoner, had remarked the scars on his back, the dislocation of the left shoulder, the badly repaired break to the ulna . . .? I think he decided at that point that any action he was planning against such a leathery old campaigner was a bit limp in comparison.’

‘Good Lord!’ said Bonnefoye faintly, inspecting Sir George with fresh and wondering eyes.

‘Joe! Come now!’ George reprimanded. ‘Ulna? Wasn’t aware I had one . . . Are you quite certain that’s not one of Napoleon’s victories?’ He turned confidingly to Bonnefoye. ‘It wouldn’t do to believe everything this man tells you,’ he advised with a kindly smile for the young Inspector. ‘He enjoys a good story! Keen reader of the Boy’s Own Paper, don’t you know!’

‘Oh, I see!’ Bonnefoye was embarrassed to have been caught out so easily. ‘Well, for a moment, Commander, you had me fooled too! But then, I was always a sucker for tales of derring-do.’ Bonnefoye looked from one to the other, suddenly wary and mistrustful of these two Englishmen who seemed to share the same lazily arrogant style, the same ability to look you in the eye and lie.

He flicked a speculative glance at Joe. Surely he was aware? Could he possibly have been taken in by that performance in the interview room?

‘And now – back to your hotel, George,’ said Joe. ‘Where are you staying?’

‘Hotel Bristol. Rue du Faubourg St Honoré. D’you know it?’

‘Ah, yes. Handy for the British Embassy. Well, a bath and a change of clothes and about twelve hours’ sleep are all on the menu. And when you wake up, there’ll be a policeman by your bedside waiting to take down your statement. Leaving out the invention and prevarication, this time. No more lying! Nothing less than your uncensored revelations will do. And the policeman will be me.’