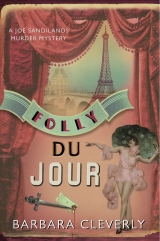

Текст книги "Folly Du Jour"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Chapter Twenty-Seven

‘Sir George! At last! Welcome, sir. How good to see you out and about again . . . Gentlemen . . .’

Beneath Harry Quantock’s bluff greeting Joe sensed a trickle of tension flowing.

‘To see Pollock? Well, of course . . . and yes, he is in the building at the moment. Um . . . look – why don’t you come along to his study and wait for him there? I’ll have him paged. He’s upstairs in the salon dancing attendance on the Ambassador’s lady. Actually,’ he confided, ‘this could be rather a bad moment. They’re just about to take off for the opera. His Excellency can’t abide the opera so John usually undertakes escort duties. Are you quite certain this can’t wait?’ Oh, very well . . .’

They went to wait in the study, choosing to stare at the cricket photographs rather than catch each other’s eye. George was looking confident, in his element. Bonnefoye was looking uncomfortable. Joe was just looking, taking in the neatness and utter normality of everything around him. All papers were filed in trays and left ready for the morning’s work. The flowers in one corner of the desk had been replenished. On the mantelpiece, the photograph frame surrounding his mother’s smiling Victorian features had been polished up. In the bin, a week-old copy of The Times, open at the crossword puzzle. Completed.

Pollock swept in a few minutes later, handsome in evening dress. He surprised Joe by heading at once for George, who had risen to his feet, and enveloping him in a hug. The two men muttered and exclaimed together for a while, holding each other at arm’s length to verify that, yes, both were looking in the pink of good health and Paris was obviously agreeing with them.

He turned his attention to Joe and Bonnefoye, and George introduced the young Frenchman. Pleasantries were exchanged. Joe had the clear feeling that Pollock was trying hard not to look at his watch.

‘I’m sorry to disrupt your evening, Pollock . . .’ Joe began.

‘So you should be!’ he replied with an easy grin. ‘I’m just off to hear René Maison singing in Der Rosenkavalier. A first for me – do you know it?’

‘Yes, indeed. Charming entertainment. Full of disguises, deceit and skulduggery of one sort or another. The police dash in and solve all the problems in the end, I recall. I think you’ll like it.’

George threw him a withering glance and took up the reins. ‘We have a problem, Jackie. Or rather, these two Keystone Cops have a problem. Which you can solve. I want you to tell them you’re not a degenerate and a multiple murderer.’

‘I beg your pardon? I say, George, old man . . . what is going on? I really do have to rush off, you know. Look – can you all come back and play tomorrow?’ He looked uneasily over his shoulder, hearing a party forming up in the foyer.

‘I’m afraid it’s no joke, Pollock,’ said Joe. ‘A certain accusation has been made . . .’ He abandoned the police phrasing. ‘Alice Conyers has shopped you. She’s told us everything. Her – your – organization has been shot to pieces, literally, while you’ve been sipping sherry and humming arias in Her Excellency’s ear. It’s over. The crew in the boulevard du Montparnasse are stretched out either in the morgue or on a hospital bed.’

Pollock tugged at his starched collar and sank on to a chair. ‘Alice?’ he murmured. ‘Is she all right?’

‘Right as rain. Not much looking forward to seeing you again. But she’s gone off into the night – armed.’

‘You know Alice, Jackie?’ George was unbelieving.

‘Yes. ’Fraid I do! Oh, my Lord, I knew all this would catch up with me! Never thought it would be you, old man, who brought the blade down on me, though. I say – is there any way of keeping this under our hats?’ He looked anxiously at the door again. ‘I wouldn’t like His Excellency to find out his aide is a bit of a bounder.’ He grinned sheepishly. ‘I’d have to kiss goodbye to my evenings at the opera and the ballet and the gallery openings. And I enjoy all that sort of thing enormously. I’m sure he’d understand if I explained it all in my own words and in my own time . . . I mean – we’re not Puritans here – we’re men of the world, don’t you know! The gossip would soon burn itself out . . . in fact, my image might even be burnished in some people’s eyes . . .’

Bonnefoye could keep silent no longer. ‘Bloody English! Is this the understatement you are so proud of, Sandilands? Six deaths in three days, your own life in danger, Sir George a candidate for the guillotine and the perpetrator confesses he’s a bit of a bounder! Well – rap him over the knuckles and let’s be off, shall we?’

He got to his feet in disgust.

Joe joined him, shoulder to shoulder.

‘No joke, Pollock,’ he said stiffly. ‘Alice has told us how you took over her business and turned it sour. Used it as a base for a very hideous assassination bureau. I don’t think you were involved in any way in the Louvre murder – except as a man casually caught up by circumstances – but I do believe that you learned from that episode . . . were inspired by it . . . recognized there a service that was not supplied by anyone else. You could name your fee. No client could complain about the outcome without condemning himself. Absolute security. You became Set.’

Pollock slumped in his seat, lost in thought. Finally he waved them back to their chairs. ‘I think you’d better hear this,’ he said, heavily.

‘I fetched up here in . . . what was it, George? . . . 1923. I liked my employment. I’m good at what I do. Round peg in round hole. Ask anyone. Only two things I missed, really.’ He looked shiftily at Joe. ‘Yes, you’ve guessed – the cricket. But apart from that – female companionship. I had a mistress . . . or two . . . in Egypt, my last posting, and I was lonely here in Paris. Yes – lonely. They do things differently here.’ He smiled. ‘Oh, lots of commercial opportunities, street girls, chorus girls available. Not my style. I like women, Sandilands. I mean, I really like them. I like to talk with them, laugh, swap opinions, have a nice hug as well as the more obvious things.

‘I met Alice at the theatre one night. She spilled her drink on my shoes in the bar. Scrambled about on the carpet with her handkerchief, trying to make all well. One of her tricks, I was to discover later. Who can resist the sight of a beautiful, penitent woman at his feet? She took my address, saying she wanted to write a note of apology. She was swept off at that moment by a large and protective gentleman. You can imagine my astonishment when, next day, a box arrived for me. Containing a wonderful pair of shoes. My size – she’d established that much while she was down there. And much more expensive than any I could have afforded. I was flattered, intrigued, drawn in . . .’

Bonnefoye stirred impatiently.

‘Upshot was – I met her for tea. She told me about herself . . . quite openly . . . and the way she made a living. I was interested. I went along and approved. And then I realized what she really wanted me for.’

‘Go on.’

‘Contacts! I was to be her opening into the diplomatic world.’ He paused, reflecting, and then smiled his boyish smile again. ‘Not quite the teeming pool of skirt-chasers she had anticipated, varied lot that we are here! But I liked what she had to offer. I liked Alice! I became a regular customer. And, I had thought, until you burst in here with your hair-raising and ludicrous stories, a friend. I trusted her. I had thought we were very close. How could she? I don’t understand . . .How could . . .?’

To Joe’s horror, he saw the blue eyes begin to fill with tears and looked tactfully away.

‘My poor chap!’ said Sir George. ‘Many suffered similarly in India. Ask Joe! We all learn that the woman keeps no friends. She is totally self-interested. Unscrupulous.’ He turned angrily on Joe and Bonnefoye. ‘Now do you see what we’ve done? Jack is not one of your criminal insen-sitives, you know.’

‘You’re generous to say “we”, George. You should know, Pollock, that your cousin would hear not a word against you. He didn’t believe Alice’s story. And he was right. She used your relationship, the details of her close familiarity with you, to convince us that you were the guilty party behind these crimes.’ He gave a sharp, bitter laugh. ‘She traded a man’s reputation and possibly his life for her freedom. And who knows where the hell she is now?’

‘Out in the mists, armed, calling her Zouave to heel, planning her next murderous display?’ said Bonnefoye. ‘What clowns we are! She’s made monkeys of the lot of us! She’s the one behind it all, isn’t she? There is . . . never has been a Set.’

‘More of a Kali, perhaps,’ muttered George. ‘Indian Goddess of Death.’

‘Look, you fellows, you’ve already ruined my evening. Bursting in here like Ratty and Moley with old Badger brandishing his stick, come to tell me the game’s up . . .’ Jack Pollock grinned at George. ‘Why not come back again tomorrow and ruin my day? I’ve heard only a fraction of what you have to tell me but really – you will understand, George – when Her Excellency calls, the aide comes running. That was her calling and here I am – running.’ Pollock got to his feet. ‘Fascinating story! No – truly fascinating! You could make an opera of it.’

He went over to the desk and plucked a red rose from the vase. ‘Must get into the part, I suppose. Der Rosenkavalier – here he comes!’ He nodded his head to the three of them, stuck the rose defiantly between his teeth and made for the door.

With a sickening vision of the red roses swirling away on the current down the Seine, Joe called after him impulsively: ‘Pollock! If you have to go over a bridge, take care, won’t you? Oh, I’m so sorry! How ridiculous! Do forgive me!’

Pollock, wondering, took the rose from his teeth and threaded it through his buttonhole. ‘No bridges between here and the Opéra, Ratty. It’s a straight dash down the river bank. See you all again tomorrow, then? Harry will show you out.’

‘Bridges?’ said Bonnefoye when the door closed behind Pollock. ‘What was that all about?’

‘Oh, a phobia of mine. Some people fear snakes, some spiders, others heights . . . me – I can’t abide crossing rivers. It was the rose that triggered that display of weakness.’

George wasn’t listening. ‘Look – Jackie’s got the telephone,’ he announced. ‘Why don’t you use it to ring up your mother, Jean-Philippe? She’ll be concerned. Tell her we’re all coming home safe and well.’

‘But I never ring my mother –’

‘Then I think you should start. Not easy being the mother of a policeman.’

Bonnefoye made no move to oblige and, with a snort of exasperation, George seized the receiver and took up the earpiece. He spoke in his Governor’s voice, friendly but authoritative: ‘Hello? This is Sir George Jardine here. I’m down below and I want you to connect me with this number. It’s a city number. Got a pencil to hand, have you?’

After the usual arrangement of clicks and bangs they heard Madame Bonnefoye reply. ‘Hold on a minute, will you, madame? I have your son on the line.’ He beckoned to Bonnefoye and held out the earpiece.

‘Yes, it is me, Maman. Oh – well! Yes, it went well. A waste of our time, I think. False alarm. Nothing sinister to report. Look, we’re all going to climb into a taxi and come back for supper. We’ll need to stop off for a minute or two at the Quai to brief Fourier . . . we don’t want him inadvertently to go laying siege to the British Embassy . . . and then come straight on home. Half an hour.’

As their taxi moved off, a second, which had been waiting across the road and a few yards down, started up and slid into the busy traffic stream behind them.

Chapter Twenty-Eight

They had left George sitting in the back of the taxi in the courtyard while they trudged up the stairs to confess to Fourier that they’d been given misleading information. They emerged fifteen minutes later, silent, dismayed by the Chief Inspector’s glee at their predicament.

Before they could cross the courtyard, they were alerted by the sound of running feet clattering down the stairs after them. Fourier’s sergeant shouted their names and they waited for him to catch up with them. ‘Inspector! Sir! Message just came through to the Commissaire. Emergency down by the Square du Vert Galant. Roistering. There’s been roistering going on. They will do it! Young folk got drunk and someone’s been pushed in the river. You’re nearest, sir. Can you go down and sort it out?’

‘No. I’m busy,’ said Bonnefoye. ‘Do I look like a life guard? We have a two-man detail down there from nine o’clock onwards for these eventualities. This is for uniform. They’ll deal with it.’

‘That’s the point, sir,’ said the sergeant, puzzled. ‘Can’t be found. They’ve buzzed off somewhere. What should I do then, sir? You’d better tell me . . . just so as it’s clear.’ He evidently didn’t want to go back upstairs and report the Inspector’s refusal of an order.

Bonnefoye groaned. ‘I’ll go and take a look. But I warn you – looking’s all I intend to do. I won’t get my feet wet!’

Turning to Joe: ‘Look – not sure I like this much, Joe. It’s . . . irregular. I’d rather deal with it myself. I’m not so quixotic as you – you’d jump in to save a dog! You go on back with Sir George. I’ll grab another taxi when I’ve found those two sluggards who ought to be here.’

‘No – I’ve a better idea,’ Joe replied. ‘I’m coming with you. But we’ll send George home as advance warning that we really are serious about supper. George!’ he shouted, opening the back door. ‘Slight change in arrangements. Something to check on down by the river. You carry on, will you? Jean-Philippe and I will be along in say – half an hour. Driver, take this gentleman to the address he will give you as soon as you’re under way.’

He banged peremptorily on the taxi roof to deny George a chance to argue and watched as the taxi made its way out of the courtyard.

They began to run along the Quai des Orfèvres towards the bow-shaped point of the city island beyond the Pont Neuf. A romantic spot, green and inviting and dotted with willow trees, it was a magnet for the youth of the city with proposals and declarations to make but also for the many drunken tramps who seemed to wash in and out with the tide. A hundred yards. Bonnefoye gave warning of their approach by tooting insistently on the police whistle he kept in his pocket. No duty officer came hurrying up to join them with tumbling apologies.

‘Why us?’ Bonnefoye spluttered. ‘A whole bloody building full of cops behind us and who’s rushing for a dip in this open sewer? We are. Must be nuts. Where are the beat men? I’ll have their badges in the morning!’

They paused to get their breath back on the Pont Neuf. The loveliest bridge, Joe thought, and certainly the oldest, it spanned the Seine in two arms, divided almost exactly by the square. Centuries ago it had been a stage as well as a thoroughfare and market place, a paved space free of mud where comedy troupes could perform. The Italian Pantaloon, the clown Tabarin, uselessly flourishing his wooden sword, had drawn the crowds with burlesque acts of buffoonery. In an echo of the rather sinister jollity, each rounded arch was graced with a stone-carved gargoyle at its centre, grinning out over the river. Joe and Bonnefoye added their own stony profiles to the scene as they peered over the parapet into the gloom, searching the oily surface of the fast-flowing water, the only illumination the reflections of the gas lamps along the quays and a full moon dipping flirtatiously in and out of the veils of mist rising up from the river.

‘Spring surge,’ said Bonnefoye. ‘Quite a current running. If anyone’s fallen in there, they’ll be halfway to Le Havre by now. Hopeless. Listen! What can you hear?’

‘Nothing.’

‘Exactly. No one here. Not even a clochard. At the first sign of trouble they’re off. So there has been some trouble, I’m thinking. Sod it!’

A strangled scream rang out from below in the park and to the right. Male? Female? Impossible to tell.

‘Here we go,’ groaned Bonnefoye. ‘I’ll go down and investigate. You stay up here and be spotter. Give me a shout the moment you see something.’ He clattered off down the stone staircase to the lower level, still tooting hopefully.

Left alone on the bridge, Joe clung with tense fingers to the stonework of the parapet, steadying himself. It always hit him like an attack of vertigo. A combination of height and the insecurity of seeing a dark body of water sliding, snakelike and treacherous, beneath his feet. He closed his eyes for a moment to regain control and heard Bonnefoye’s whistle cut off in mid-blast.

Joe looked anxiously to his left, aware of a slight movement along the bridge. A tall figure was approaching. He moved nearer, coming to a halt ten yards distant, under a lamp, deliberately showing himself. Dark-jawed, unsmiling, chin raised defiantly to the light, right hand in pocket. The Zouave. Waiting.

Angrily, Joe looked to his right to check his escape route and his second nightmare hit him with the force of a bolt of electricity. His body shook and he fought to catch his breath. A figure, also ten yards distant. Not so tall as the first but infinitely more terrifying. He could have been any gentleman returning from a show, shining silk top hat on his head, well-tailored evening dress, white waistcoat, diamond studs glittering in his cuffs. Urbane, reassuring, romantic even, until you noticed the black mask covering the upper half of his face. In a theatrical gesture, he raised his left hand, white-gloved, to cup his chin, looking speculatively at Joe. His right hand, ungloved, went up and slightly behind his back. Slowly enough to show the gleaming zarin it held.

Joe began to breathe fast, steadying his nerves. Two men. He didn’t fancy his chances much. He thought, on the whole, he’d go for the toff first. The leader. Though by the time he’d closed with him, the Zouave would have sunk his knife into his back. Take the Zouave first and the Fantômas figure would be ripping his throat out from behind. He remembered Dr Moulin’s hands in the morgue, clutching his hair, demonstrating the hold, and his skin crawled. That’s how it would happen.

No gun, he’d have to fight with his fists and feet. Then he remembered the doctor’s parting concern and his strange gift. He felt in his pocket, encountering the cold steel of the surgical instrument. Better than nothing and they wouldn’t be expecting it. These creatures only attacked the defenceless and the unready, he told himself. ‘It’s razor-sharp,’ the doctor had warned. But all Joe’s instinct was pushing him to explore, to handle his weapon. To decide – slashing or stabbing? Which would be the more effective? His safety – his life – depended on the quality of the steel implement. By the time he closed with his assailant, it would be too late to find out. Worth a cut thumb to be certain. And the quick flare of pain would jolt his senses fully awake. Tentatively he ran a thumb along the cutting blade. He repeated the gesture, more urgently, pressing his thumb down hard, the whole length of the cutting edge. And moaned in distress.

There was no edge. It was blunt. Not a scalpel. It was as much use to him as a fish knife. He held it in his hand anyway because he had nothing else. It would still glitter in the gaslight. It might fool them into thinking he was armed. And then, with a rush, with a flash of insight that came hours too late, he realized.

He could deceive no one. He was himself the fool. No mistake had been made when he was handed the useless tool. It was a stage prop. He was standing here, gaslit from both sides, at the stone prow of the island, framed up for his audience below, a modern-day Mr Punch. The only thing lacking was the cap and bells on his head and the hurdy-gurdy musical accompaniment.

Strangely, he felt a compulsion to play the part handed to him. To let them know that, however belatedly, he had worked it out. He held up the instrument before his eyes in a parody of a scene from Macbeth. ‘Is this a scalpel which I see before me?’ he mused. ‘Or could it be an earwax remover?’

He looked to the right again and saw the smile start in the masked eyes, the nod that acknowledged his moment of understanding. He looked to his left and the Zouave with panther stride began to close on him. He pushed the scalpel back into his trouser pocket, took a deep breath, put both hands on the parapet and vaulted over, leaping as far out into the void as he could manage, hoping he’d miss the built-up quayside and hit the water.

The cold of the spring surge waters knocked the breath from his body and he struggled to the surface gasping and choking. The stench of the river water was sickening. An open sewer, Bonnefoye had called it. He stared as a dead dog, bloated and disgusting, swept towards him and then bobbed away before it made contact. He struck out for the bank, glad enough to be carried by the current at an angle to the Pont Neuf, away from the two creatures on the bridge. He wasn’t a strong swimmer and his jacket was heavy with the weight of water, dragging him down. He spent a few moments treading water while he struggled out of it. Noises behind him. A gunshot rang out. He ducked under the surface and allowed himself to drift a few more yards.

They could with ease plot his course downstream, he thought, with the treacherous moon now lighting up the river like a satin ribbon. One could remain on the bridge watching for him to break surface, the other could intercept him at any point along the quay, and be there, standing waiting, while he struggled on the greasy cobbles that revetted the quayside. He would have to slip and slide and claw his way up over the green scum only to find a fresh and armed adversary looking down on him. Might as well drift straight down the centre and head for – what had Bonnefoye said – Le Havre?

And then anger took over. He’d been fooled. Completely fooled. He raged. His aggression mounted. He kicked out for the bank again. They could at least only take him one at a time now. And he wasn’t intending to go down easily. Whichever man had run down to confront him there on the quay was going to take his life at some cost. He didn’t want his body to be pulled, leaking water and bodily fluids, from the Seine miles downstream. To fight and die up there in the open air had, in a few short minutes, become his only goal.

A dead rat floated by, brushing his face. Retching with horror, Joe trod water, waiting for it to pass, but then, on an impulse, he reached out and seized it and squashed the swollen body down inside the front of his shirt. A gassy eructation burst from the rat and Joe gagged and spluttered. Then he gritted his chattering teeth. ‘Brother Rat!’ he muttered, knowing he was on the verge of hysteria. ‘More where that came from? Let’s hope so!’ He was as prepared as he could ever be for the confrontation. He just hoped that his enemy would feel impelled, as most villains did, to explain himself. To talk. To give Joe time to get his breath back and plan his retaliation.

If he encountered the Zouave he could rely on no such reaction. His only language was Death and he would deliver it in one unanswerable word.

Taking his time, steadying his breathing, he judged the moment and made for the part of the quay where a set of slippery steps had been made for the use of the river traffic. Panting, he pulled himself together, taking the useless scalpel in his right hand.

‘Thought you’d make for this place. How are you enjoying the show, so far, Commander?’ The remembered voice purred down at him from the top of the steps.

There was the Fantômas pose again. Eyes glittered through the holes in the mask.

Joe responded in short panting phrases, one for each step as he climbed. ‘Not the best evening I’ve spent in the theatre. Never been fond of melodrama. Overacting sets my teeth on edge. Kinder not to look, really. I’ve decided to bale out at the interval.’

He’d got almost to the top. Near enough. This would do. Affecting a gulping cough, he put his left hand to his chest and seized the rat, grasping its slimy fur in his fingers. ‘I was wondering, Moulin . . .’ he began and a moment later had hurled the squashy and stinking corpse into the masked face. The man took an instinctive step back, with an exclamation of disgust, hitting out at the creature with his left hand. In an instant Joe had closed with him, pushing him off balance, a frozen but iron-hard left fist closing over the knife hand and squeezing with the fury of a madman. The zarin clanged on to the cobbles and the man looked down and sideways to find it.

A moment of inattention which cost him the sight of his left eye. Joe brought up the blunt scalpel and drove the point through the nearest hole in the mask.

A yell and a curse broke from him but he struggled on, strong right hand breaking free from Joe’s slippery clutch. He scrambled to pick up his knife. With the scalpel still sticking out of his eye socket, he rounded on Joe, screaming, beside himself with fury, knife once again clutched in his hand. With both his feeble defences used up, Joe crouched and circled, only his fists left and his cunning. He was intending to work his way around his enemy, wrong-foot him and push him into the river.

Just as he was beginning to think he stood a chance, another shot rang out. The nightmare figure was hurled backwards away from Joe by the force of the bullet tearing into his chest. A dark stain was already spreading over the white waistcoat before he collapsed on to the cobbles inches from the drop into the river.

Joe, shaking with cold and effort and shock, could only turn his head and mumble, ‘Bonnefoye? Jean-Philippe, is that you?’ into the darkness.

‘Er, no. It’s me, my boy,’ said Sir George, emerging from the shadows, Luger in hand. ‘Thought you were up to something sending me off like that. Nosy old bugger, as I keep reminding you. Not so easy to shake off. Had to investigate. Who’s your friend?’

He moved over to the body, pistol at the ready, Joe noticed.

‘Who was your friend. He’s dead. Police not very popular in these parts, I see. I had to take strong action to disable the other bloke on the bridge who seemed to be taking too close an interest. Vévé, I’m assuming. He’s dead too, I’m afraid. But, Joe, who was this fool?’

George bent and tugged the mask off the dead face, carefully pulling it away from the scalpel which still projected.

‘No fool! Madman perhaps? Moulin. The doctor. The pathologist.’

‘Pathologist? Is he so short of customers he has to . . . oh, sorry, Joe. It just seems very peculiar to me. So, he’s the one who fancied himself as Set, is he? But why on earth is he got up like this? Was he on his way to a masked ball?’

‘He didn’t have time to explain. I’m just guessing this was his last commission. Someone paid to watch me die, George. But where on earth has Jean-Philippe got to? He was down in the square, whistling . . . Oh, my God! There were three of them!’