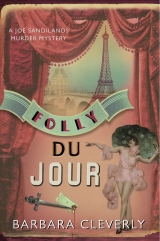

Текст книги "Folly Du Jour"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

A good witness, Joe thought.

‘The one you say died . . .’ Out came the right hand again. ‘I last had a glimpse of him halfway, I suppose, through the finale. I don’t have a lot to do in that routine – just prance around in gold feathers – and I remember being something put out – he was looking at his watch! Turning it this way,’ she held up an arm and demonstrated, ‘towards the stage lights, you know, to get a look at it. And he stared across at the other box. I was beginning to think we were losing the audience. Feller looked as though he couldn’t wait to take off.’

‘Strange behaviour?’ murmured Joe.

‘Well, exactly! Lord! If a hundred naked girls – and me! – can’t knock his eye out, whatever will?’

‘A good question, Miss Baker. What better entertainment can he possibly have wanted?’

Bonnefoye looked curiously at Joe, who had lapsed into silence, and he seemed about to speak but he was interrupted by Josephine who, half-rising, was drawing the conversation to a close. ‘Still, sorry to hear the old goat died.’

‘Don’t be,’ said Bonnefoye, getting to his feet. ‘The man was more of a cold-hearted snake and he got off lightly. Don’t give him another thought.’

Simenon showed them to the side door and said goodbye. ‘You will let me know how all this turns out?’ he said hesitantly. ‘I’ve been most intrigued . . .’

‘And helpful,’ said Bonnefoye. ‘We’ve been interested to hear your insights, monsieur.’ He hesitated for a moment. ‘Look. You’re a crime reporter. You must be keen to see how we live over there at the Quai? Take a peek inside? Have you ever been? Well, why don’t you come over and see me there when this is all over? I’ll fill you in. My turn to give you the tour!’

‘Bit rash, weren’t you?’ Joe commented as they walked away back into the avenue de Montaigne. ‘Fourier won’t like that.’

‘Sod Fourier! I can swing it! Anyway – with the ideas you’ve been stuffing into his head, a newsman might be just exactly what he wants to encourage . . . “Now, my dear Simenon, just take this down, will you?” Chaps like that are very useful to us. They’re a channel. They’re not exactly informers but – well, you heard him – he talks to people who’ll accept a glass from him and open their mouths but who wouldn’t be seen within a hundred yards of a flic. They can pass stuff to the underworld we can’t go out and shout through a megaphone. He seemed to be able to take a wide view of things. Man of the world.’

‘And quite obviously something going on between him and the star, wouldn’t you say?’

‘Oh, yes, of course. Good luck to them! How did he say they met? Stage-door Johnny, didn’t he say? Just turned up on the off-chance?’

‘Yes. But not empty-handed,’ said Joe thoughtfully. ‘Said he brought her a bunch of roses. Roses . . . lilies . . .’ He looked about him. ‘We’re a long way from a florist’s shop here. But there must surely be some enterprising merchant out there catering for star-struck young men on their way to the theatre?’

‘Place de l’Alma,’ said Bonnefoye, turning to the right and walking towards the river.

‘Lilies? Two dozen? Yes, of course. Not every day I shift two dozen in one go! Lucky to get rid . . . they were just on the turn. I told him: “Put them straight away in water up to their necks.” Must be nearly two hours ago. That’s right – the bell on the Madeleine had already rung two. But not the half past . . .

‘What did he look like? Oh, a handsome young chap!’ The fleuriste turned a toothless smile on Joe and cackled. ‘To my old gypsy eyes at least. Rather like you, monsieur. Your age. Young but not too young. Tall, well set up. Dark skin. Southern perhaps? North African even? Mixed probably. Sharp nose and chin. Well dressed. Nice hat. Lots of money.

‘You’d need lots of money to buy all those lilies! His wallet when he took it out to pay for them was stuffed! Wished I’d asked double! He didn’t really seem interested in the price. Some of them haggle, you know. This one didn’t. Paid up, good as gold.

‘Scar? Can’t say I noticed one . . . I did notice the bristles though. He’s growing a beard. It’ll be a fine black one in a few weeks’ time.

‘Where? Oh, he walked back up the avenue towards the theatre.’ The old woman grinned. ‘Probably spotted some young dancer on the front row. He’ll certainly impress her with those flowers anyway!’

Sensing they were about to close up the interview, she recalled their attention: ‘Do you want to know what he was doing before he came to my stall?’

A further five francs changed hands.

‘He was wandering about on the bridge. Looking at the statues,’ she said. ‘Now, gentlemen, I’ve got some lovely red roses fresh in from Nice this morning if you’re interested . . .’

‘Heard enough?’ said Bonnefoye using English, in a voice suddenly chilled. ‘She’s scraping the barrel now.’ And then: ‘He’s not exactly hiding himself, is he? He must have known we’d trace him here to this stall.’

‘He’s watching us at this moment,’ said Joe, managing by a superhuman effort not to look around. ‘Down one of those alleys, at one of those windows. Under the bridge even.’

Bonnefoye carefully held his gaze and Joe added: ‘So, let’s assume that, just for once, it’s we who have the audience, shall we? And give him something to look at.’

He turned to the flower seller. ‘Thank you, madame. I’ll take two dozen of those red roses from Provence.’

The old woman stood and moved a few yards to watch them as they went down to the river. When she saw what they were about, she shook her head in exasperation. Idiots! Mad foreigners! Had they nothing better to waste their money on? They’d taken up their position halfway along, leaning over the parapet, and, taking a dozen blooms each, were throwing the roses, one at a time, downstream into the current.

She pulled her shawl tighter about her shoulders and crossed herself. She watched on as the swirls of blood red eddied and sank. How would those fools know? That what they were doing brought bad luck? Flowers in the water spelled death.

Chapter Twenty-One

Bonnefoye had returned to the Quai des Orfèvres to pass on instructions for the fingerprint section and to check whether they’d made any progress with the Bertillon records of scarred villains. He’d been reluctant to let Joe turn up unaccompanied at the jazz club on the boulevard du Montparnasse, offering, as well as his own company, the presence of a team of undercover policemen in reserve.

Joe had reassured him. ‘Don’t be concerned . . . Just think of it as a visit between two old friends . . . Yes, I think I can get in. I’m prepared.’ He patted his pocket. ‘A bird has led me to the magical golden branch in the forest. I only have to brandish it and the gates to Avernus will swing open. As they did for Aeneas.’

Bonnefoye had rolled his eyes in exasperation. ‘The gates can swing shut as well. With you inside. And I’m not too certain that Aeneas had a very jolly time. Full of wailing ghosts, Avernus, if I remember rightly. If you’re not out by eight, I’m storming the place. I mean it! Now here’s what I’m offering . . .’

Joe waited until six o’clock when the crowds hurrying in through the door made him less conspicuous. He went to the bar and ordered a cocktail. He asked for a Manhattan and threw away the cherry. A Manhattan seemed the right choice. The combination of French vermouth and American bourbon, spiked with a dash of bitters, was in perfect harmony with this atmosphere. Throaty, fast Parisian arpeggios studded a base of slow-drawing transatlantic tones and the band also seemed to be an element in the blend. Setting the scene, in fact, Joe thought, as he listened eagerly. Excellent, as Bonnefoye had reported.

A black clarinettist doubling on tenor saxophone was playing the audience as cleverly as his instruments this evening and there was a jazz pianist of almost equal skill. A banjo player and a guitarist added a punchy stringed rhythm. Not an accordion within a mile, Joe thought happily. Generously, the instrumentalists were allowing each other to shine, turn and turn about, beating out a supporting and inspired accompaniment while one of the others starred. To everyone’s delight, the pianist suddenly grabbed the spotlight, soaring into flight with a section from George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue and Joe almost forgot why he was there.

Damn George! If it hadn’t been for his officious nosiness, Joe could have been here, plying Heather Watkins with pink champagne, relaxing after a boring day at the Interpol conference, just a couple of tourists. She’d have been laughing at the new cap he’d bought and flattened on to his head, wearing it indoors like half the men in the room. Instead, he was crouching awkwardly, sitting slightly sideways on his bar stool to disguise the bulge of the Browning on his hip and hoping that no friendly American would fling an arm around him, encountering the handcuffs looped through his belt at the small of his back.

He glanced around at the crowd. Not many single men but enough to lend him cover. The one or two who appeared to be by themselves had probably chosen their solitary state, he reckoned. He saw two men line up at the bar, released from the company of their wives whom they had cheerfully waved off on to the dance floor in the arms of a couple of dark-haired, sinuous male dancers. What had Bonnefoye called them? Tangoing, tea-dance gigolos. Everyone seemed pleased with the arrangement, not least the husbands. On the whole, a typical Left Bank crowd, self-aware, pleasure-seeking, rather louche. But then, this wasn’t Basingstoke.

He enjoyed the clarinettist’s version of ‘Sweet Georgia Brown’ and decided that when he spiralled to a climax, it would be time to move on.

He ducked into the gentlemen’s room and checked that, as Bonnefoye had said, it was no more than it appeared and waited for a moment by the door he held open a finger’s breadth. No one followed him. A second later he was walking up the carpeted stairs towards the three doors he’d been promised at the top on the landing. And there they were. The middle one, he remembered, was the one behind which the doorkeeper lurked.

The building itself was a stout-hearted stone and rather lovely example of Third Empire architecture seen from the exterior. But it had been drastically remodelled inside. The original heavy wooden features had been stripped away and replaced with lighter modern carpentry and fresh bright paint. Entirely in character with the new owner, Joe suspected.

He fished in his pocket for his ticket to the underworld, thinking it might not be wise to be observed digging about as for a concealed weapon at the moment when the doorkeeper turned up. And the mirrors? Just in case, he offered his face to the fanlight, grinned disarmingly, and waited for Bonnefoye’s promised monster.

A moment later the door opened and he was peremptorily asked his business by a very large man wearing the evening outfit of a maître d’hôtel. Bonnefoye, for once, had not exaggerated. The attempt to pass off this bull terrier as a manservant could have been comical had he not seemed so completely at ease in his role. He was not unwelcom-ing, he merely wanted to know, like any good butler, who had fetched up, uninvited, on the doorstep.

Joe held out the book he’d bought that morning.

‘This is for madame. Tell her, would you, that Mr Charles Lutwidge Dodgson . . .’ He repeated the name. ‘. . . is here and would like to speak to her.’

It’s very difficult to avoid taking a book that someone is pressing on you with utter confidence. The man took it, looked at Joe uneasily, asked him to wait, and retreated, closing the door behind him.

A minute later, the door was opened again. He saw a slim blonde woman, giggling with delight and holding out her arms in greeting.

‘Mr Dodgson, indeed!’ She kissed him on each cheek. Twice.

‘We can all make use of a pseudonym at times,’ he said, smiling affably and returning her kisses. ‘Good to see you again, Alice.’

The giant appeared behind her, a lowering presence. She turned to him and spoke in French. ‘Flavius, my guest will hand you his revolver. House rules,’ she confided. ‘I see you still carry one on your right hip, Mr Dodgson.’

Joe traded steely gazes with Flavius as he handed over his Browning. The man’s head was the size of a watermelon and covered, not in skin, but in hide. Cracked and seamed hide, stretched over a substructure of bone which had shifted slightly at some time in his forty years. Wiry grey-black hair sprouted thickly about his skull but had been discouraged from rampant growth by a scything haircut. It was parted into two sections along the side of his head by an old shrapnel wound. Or a bayonet cut. His hands resembled nothing so much as bunches of overripe bananas. Joe wondered what pistol had a large enough guard to accommodate his trigger finger.

‘Thank you, that will be all, Flavius,’ said Alice daintily. ‘I’ll call you if we need to replenish the champagne.’

‘Or adjust the doilies,’ said Joe.

‘May I just call you, as ever – Joe?’ she said, switching back to English when her guard dog had stalked off on surprisingly light feet. She held up the copy of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, with a peacock’s feather poking out from the pages as he remembered it on her shelf in Simla. The hat maker in the rue Mouffetard had been puzzled and amused by his request that morning and had refused payment for such a small piece of nonsense but it seemed to have worked. Alice was still laughing. ‘Do you know, I never did get further than the page marker! I got quite bogged down in the middle of a mad tea party.’

‘The reason most of us leave India,’ Joe suggested.

‘Yes indeed! But, as you know, it wasn’t boredom that drove me away! I was having a happy time. It was Nemesis in the shape of a granite-jawed, flinty-eyed police commander who chose to delve too deeply into my business affairs.’

Joe decided to bite back a dozen objections to her light summary of a catalogue of murder, theft and fraud. ‘Not sure I recognize him. Shall we just say something came up and you had to leave India in a hurry?’

‘You came up, you toad! And here you are again, doing what toads do! Now the question is – shall I step on you and squash you or invite you inside and give you a kiss?’

‘I think it’s frogs that are the usual recipients of oscula-tory salutations,’ he said cheerfully.

Alice groaned. ‘Still arsing about, Sandilands? Can’t say I’ve missed it! But come in anyway.’

He followed her trim figure along the corridor. Dark red cocktail dress, short and showing a good deal of her excellent legs. Her shining fair hair, which had been the colour of a golden guinea he remembered, was now paler, with the honey and lemon glow of a vin de paille. It was brushed back from her forehead and secured by a black velvet band studded with a large ruby over her left ear. Had her eyes always had that depth of brilliant blue? Of course, but in the strait-laced society of Simla, she had not dared to risk the fringe of mascara-darkened lashes. She still had the power to overawe him. He found himself looking shiftily to left or right of her or down at her feet as he had ever done and was angry with his reaction.

‘Joe, will you come this way?’ She turned and, stretching out her right hand, invited him to enter a salon. Distantly, sounds of the jazz band rose through the heavily carpeted floor and he realized they must be directly over the jazz café. She closed the door and they were alone together.

‘Champagne? I was just about to have a glass of Ruinart. Will you join me?’

‘Gladly.’

She went to a buffet bearing a tray of ice bucket and glasses and began to fill two of the flutes, chattering the while.

‘Cigarette? I’m told these are good Virginian . . . No?’ She screwed one into the end of an ebony holder and waited for him to pick up a table-lighter and hold the flame steady while she half-closed her eyes, pursed her scarlet mouth and drew in the smoke inexpertly. Joe read the message: English vicar’s daughter, fallen amongst rogues and thieves and ruined beyond repair, yet gallantly hanging on to some shreds of propriety. He was meant to recall that, for someone of her background, smoking was a cardinal sin. He smiled. He remembered her puffing away like a trooper at an unfiltered Afghan cigarette in Simla.

‘Five years?’ she asked, her thoughts following his, back into the past. ‘Can it really be five years since we said goodbye to each other on the steamer? You’re doing well, I hear. And I hear it from George of all people. We met at the theatre the other day. Did you know he was in Paris?’

‘Yes, I did. But tell me how you knew he was going to be here, Alice.’

‘No secret! You know my ways! In India I was always aware of who exactly was coming and going. It’s just as easy to keep track of people over here if you know the right man to ask. And the French are very systematic and thorough in their record keeping. A few francs pushed regularly in the right direction and I have all the information I need at my fingertips or rather in my shell-like ear . . .’ She glanced at a telephone standing on a table by the window. ‘Bribes and blackmail in the right proportions, Joe. Never fails. Tell me now – how did you find George? Is he all right? I heard a certain piece of nastiness was perpetrated after I left the theatre. I’m guessing that’s why you’re here?’

Alice shuddered. ‘I blame myself. If I hadn’t shot off like that, he would never have gone over and got himself involved with all that nonsense. Look, Joe, I’d rather not break surface and I’m sure you can understand why but if he’s desperately in need of help, then – oh, discretion can go to the winds – the man’s a friend of mine. I do believe that. I always admired him. If I can say anything, sign anything to get him out of that dreadful prison, then I will. That is why you’re here, Joe?’

‘No, it’s not. And don’t concern yourself about George. No action required – I’m sure I can manage.’

‘I’m assuming he is still over there on the island?’ she asked less certainly. ‘Or have you managed to get him out?’

‘He’s in police custody,’ said Joe, looking her straight in the eye. Alice had, he remembered, an uncanny way of knowing when she was being told a lie. And she was likely to have developed such a skill leading the dubious life she’d led. He wouldn’t have trusted himself to tell her anything but the truth. ‘Still in the hands of the French police,’ he said again. ‘He’s not enjoying the downy comfort of the Bristol which is where he ought to be but I’m pleased for him to be where he is. For the moment. I don’t believe Paris to be an entirely safe place for him. I’ve persuaded Commissaire Fourier, in charge of the case, to go more easily on him – the Chief Inspector seems to think he ought still to have the use of medieval methods of extracting a confession as well as the medieval premises.’

‘Poor, dear George! You must do what you can, Joe!’

‘Of course. I visit every day. I’m happy to report the bruises are healing. He enquired after you when I saw him this morning. Wanted to know that you are well and happy.’

‘Ah? You will reassure him then?’

‘Can I do that? Tell me – what should I report of little Alice in Wonderland? Business good, is it?’

For a moment she was taken aback. ‘My businesses always do well. You know that, Joe. Until some heavy-footed man comes along and stamps them into the mud.’

He decided to go for the frontal attack. ‘So – how do you get on with the management of the Sphinx? Your competitors can’t have been too enchanted when you came along and set up here in their rabbit patch. Have you come to some amicable agreement? Equable share of the lettuces? They have a Paris bank underpinning them financially, I understand. I wonder how you manage, Alice? A single, foreign woman?’ He shook his head. ‘No. Wouldn’t work, would it?’ And, abruptly: ‘Who’s your partner?’

He saw the moment when she made up her mind. Alice hadn’t changed. She was behaving as she had done years ago. Why not? It had deceived him then. Wide-eyed, she was about to plunge into a confession to a sin she knew would revolt him, a sin in his eyes so reprehensible it would distract him from and blind him to the deeper evil she must keep hidden at all cost.

‘Very well. I see you’ve worked it out. I run a brothel. The very best!’ She made the announcement as though she’d just made a fortune on the stock exchange and wanted him to share in celebrating her good luck. ‘Even you, old puritan that you are, Joe, could hardly object. My clients are the cream of society. The richest, at any rate . . . They demand and I supply the loveliest girls, dressed by Chanel, jewels by Cartier, conversation topics from the New Yorker.’

‘I understand. Expensive whores. Is that what you’re dealing in these days? But, of course, you learned a good deal from Edgar Troop, Brothel-Master Extraordinaire, branches in Delhi and Simla.’

‘These girls aren’t whores! They are hetairai – intelligent and attractive companions!’ Pink with anger, she put out her cigarette, creasing her eyes against the sudden flare of sparks and smoke. Calculating whether she was wasting her time in self-justification. ‘You are not in England, Commander. Are you aware of the expression maison de tolérance?’

‘I have it on my information list, just above magasin de fesses and abattoir,’ he said brutally. ‘Knocking shop and slaughterhouse, to translate politely.’

‘Tolerance!’ she replied angrily. ‘These establishments are exactly that – tolerated – not hounded out of existence by hypocrites like you. As long as the ladies succumb to their weekly health check – the doctor visits – we break no rules. So, if you’ve come to threaten me, I’m not impressed. If the Law can’t close down those abattoirs in the rue de Lappe, they’re hardly likely to turn their attention on me. Not with the list of habitués I have . . . députés, industrialists, royalty, diplomats . . . senior police officers,’ she finished triumphantly. ‘You will be seen leaving. You may be sure of that! I may even send your superior a photograph to show how his pet investigator adds to his expenses.’

Her lip curled as she played with an amusing thought. ‘Though, in the manly English way, he’d probably summon you to his office to compare notes.’

‘Probably,’ Joe agreed, the further to annoy her. ‘Tell me – where do you recruit? I can’t see you standing in line with the other pimps at the Gare du Nord?’

‘My girls are top drawer! Your sister was probably at school with some of them . . .’ she added defiantly. ‘Some of them I found in the music hall line-ups, some had just run away to Paris for excitement, some are escaping violent men in their lives . . . Not many openings for unsupported girls in these post-war days, you know. Men have flooded back and elbowed women out of the jobs they’d found in fields, factories and offices –’

‘Spare me the social treatise, Alice!’ Joe growled. ‘You look ridiculous on that soap-box, champagne glass in hand, a hundred quid’s worth of ruby over your left ear and twenty girls on their backs down the corridor, working for you.’

If she attacked him now, as he was hoping, he could have the handcuffs on her without a second thought. He’d find it easier than requesting politely that she extend her hands.

‘Very well,’ she said, ignoring his jibe, and added angrily to annoy him: ‘Starry-eyed romantic that you are, I know you’ll not believe it when I tell you – some of my girls actually don’t at all mind the way of life. They’re paid well and cared for. I care about them and their welfare. They’re fit and happy. See for yourself if you like. An hour or two on the house? No? Well, perhaps you can accept another glass of champagne?’ She put out a hand.

He nodded, looking at her with stony face. ‘Why don’t you let me do that?’ He went to the sideboard and refilled his glass, taking the opportunity of positioning himself between her and the door.

‘And is she well and happy, the little miss who was encouraged to enter the wild animal cage with Somerton the evening before last? The bait you hobbled for the tiger? Did you warn her about the character of the man she was to entertain?’

Alice laughed. ‘Watch out, Commander! Your soft centre’s oozing out of that hard crust! Something you have in common with Sir George. Makes me very fond of the pair of you! My girl wasn’t in the slightest danger. I was on hand.’

‘Because you knew it was never intended that she should finish the evening with him. At a given signal the two of you donned your silken cloaks and disappeared into the Paris night. Or did one of you – both? – lurk behind to ensure the killer had easy access to the box?’

‘How the hell?’

‘A wardrobe of four midnight-coloured cloaks – I’m guessing that your girls, or a small picked unit of them, are actively involved in the other branch of your operation here. A sort of alluring Flying Squad? An undercover ops unit? You were always a showman, Alice. You enjoy playing games. And reading novels. Inspired by The Three Musketeers, were you? Well – listen! – this is where it all gets terribly serious.’

He put down his glass on a low table and stood ready to knock her to the floor if she tried to get past him or move towards the bell. To his surprise, she retreated away from the door and went to stand, a hand on the mantelpiece, at the other end of the room. He followed her, careful to position himself ready to block her exit.

‘I’ve got handcuffs in my pocket. Real, steel ones, not forgiving flesh and blood ones. They’ll be round your wrists and I’ll be pulling you with me down the stairs and out into the street before you can say knife. And I’ll hand you straight over to the lads of the Brigade Criminelle who are waiting below. You can sample the accommodation at HQ for yourself. Not sure which of the murders you’ll confess to but eventually you will confess. I don’t imagine even your partner’s influence spreads as far as the inner reaches of the Quai des Orfèvres. He wouldn’t be trying hard to ride to your rescue at any rate, I’d guess. And you’ll have lost again, Alice, to a man who’s made use of you. He’ll wait, knowing you won’t give him away, because by doing so, you implicate yourself. He’ll sit it out until the storm’s blown over . . . until the guillotine at La Santé has silenced you permanently and then he’ll start up again. Madames are ten a penny. He can probably raise one from the ranks with no bother at all.’

‘I’m not sure what you expect me to say. How can I respond to these maunderings? Partner? Who is this partner you rave on about?’

‘The head of the assassination bureau. The undertaker of delicate commissions. Murder with a flourish. That partner. Or should I say – boss? Two compatible services under one roof. The White Rabbit, the jazz club, and its escape hole up here into Wonderland – your part of the organization, I would expect – and then there’s the other. The Red Queen, I suppose we could call it. Wasn’t she the one who rushed around calling “Off with his head”? Or didn’t your perusal of the text take you that far? She was quite insane, you know, and incapable of discriminating. Innocent or guilty, it didn’t matter to her. Heads rolling was all she cared about. And so it is with your partner in crime.’

His voice hardened. ‘I’ve seen his handiwork. Somerton’s head was damned near severed. A youth of sixteen had his living lips stitched together. His sister had her neck broken and her mouth stuffed with banknotes because someone thought she’d spoken to me. Three deaths in as many days! You’re sheltering Evil, Alice!’

‘By God! You haven’t had time to put all this together! Who’ve you been talking to?’ She looked wildly around the room.

‘You’ll be safer with me in my handcuffs, so stop looking at the bell. Every street urchin, every tramp under the bridge will know by this evening what you’ve been up to. It’ll make the morning editions. The authorities may turn a blind eye to whoring but they still disapprove of murder. From this moment, you’re a liability. Perhaps if I left you running loose he’d devise in his twisted, sick mind a way of bumping you off in a spectacular and appropriate way. Let me think now! What could it be? Found strangled with a silk stocking in the bed of Commissaire Fourier? I like that! I’m sure I’d be amused by the headline. Kill two nasty birds with one stone. Alice, you’re finished here. Yes, you’re safer with me.’

She was looking at him in horror. Distanced. Shocked. But still calculating. ‘Safer with you? You’re mad!’

‘Possibly. Leaves you with a narrow choice, Alice. You walk out of the front door with a mad puritan and negotiate your future career or stay behind with a mad sadist and die. Which is it to be?’ He looked at his watch. ‘A taxi arrived just a minute ago in front of the jazz club. I expect your sharp ears picked it up?’

She turned her head very slightly to the window. The thick cream and black curtains and closed shutters reduced the traffic noise on the boulevard to a low murmur.

‘It’s sitting there with the engine idling. We can be inside it and away into the night in thirty seconds.’

Alice had never been indecisive. The last decision he’d seen her take had been witnessed by him down the barrel of a gun. A gun trained on him.

‘Top left drawer of the sideboard,’ she said. ‘There’s a Luger in there. 9 mm. It’s loaded. Eight rounds. Safety’s on. You’re going to have to use it.’