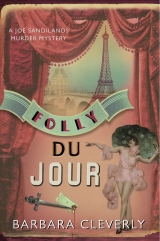

Текст книги "Folly Du Jour"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Joe doubled over and vomited up a litre of river water before he was ready to run on unsteady legs back along the bank, up on to the bridge and then down again to the level of the small park, calling out Jean-Philippe’s name. In his exhaustion, he found that George was well able to keep stride with him. They paused by the statue of Henry IV. The dashing young monarch, Le Vert Galant, the Green Sprig himself, peered majestically down from his horse at the panting old man and the drowned rat as they battled to get their breath and take their bearings.

‘There was a third man on the loose. One of the wolves. Got away during the raid. I heard Jean-Philippe whistling down here on this side. We’ll split up and search.’

‘No we won’t,’ said George firmly. ‘You stay by me. I’m not losing sight of you again. No telling what you’ll get up to. Fancy dress balls . . . midnight swimming parties . . . some fellows live for pleasure alone,’ he muttered, checking his pistol. ‘Six left. Should do it. And in the dark I don’t want to put one of them into you by mistake. Eyes not what they were, you know.’

Back to back, they quartered the ground, working their way out towards the pointed tip of the park.

They found them under a willow tree.

Bonnefoye had had no time to draw his revolver, his hands were empty, thrown out one on either side of his body. The handle of a zarin gleamed in the half-light, sticking out of his back.

George groaned. ‘Ambushed. Taken from behind.’ He expressed his grief and rage, cursing in a torrent of Pushtu.

Joe was on his knees, feeling for any sign of life. ‘George, do shut up! He’s trying to speak! He’s alive . . . just. It’s all right, old man. We’re here. Look, try to stay still. You’ve been stabbed . . . I expect you noticed . . . yes. What we’ll do, if you can bear it, is leave the blade where it is – it’s actually stopping the blood from flowing. We’ll summon up a stretcher party and get you to the hospital . . . it’s only a step or two away.’

He bent his ear to the chill mouth which was barely able to move, yet determined to convey something. ‘What’s that? Oh, yes, you got him. Or someone got him . . . The wolf. He’s lying here right beside you.’ Joe glanced down. ‘Shot through the back of the head. Small calibre bullet, I’d say. .22? But well placed. Not you, I take it? No? Ah, there’s a puzzle . . . Sorry, what did you say? . . . Yes. I’ll send George in a taxi to tell her. I’ll stay by you . . . What day? It’s Monday, old fruit . . . We’ve just had what we call in England a long weekend.’

He was grateful for the soldierly presence of Sir George, still covering the pathways with his Luger. Gently, Joe removed Bonnefoye’s police revolver from its holster and held it at the ready. But he knew the flourish was in vain. The wolf’s killer had made off into the night and was a mile away by now.

The next three days gurgled their way down life’s plughole, barely distinguishable from each other by Joe. A day of sickness and shivering, spent in Bonnefoye’s room in the rue Mouffetard, being Amélie’s replacement son while her own boy was in hospital, passed like a bad dream. He remembered the bowls of chicken soup, the cool hands on his forehead, George’s gruff voice from the doorway: ‘Just back from the hospital. Thought you’d like to hear – the lad’s going to be all right. Blade went in at an angle – the thought is that the attacker was disturbed before he could place his blow more accurately. No vital organs damaged but he lost a lot of blood. He’s on his feet already and clamouring to come home.’

The day after, which must have been a Wednesday, he spent in Fourier’s office making statements, colluding in the fabrication of various pieces of subterfuge. Nodding in agreement as the Commissaire outlined the dashing attack of the Brigade Criminelle officer (trained and directed by Fourier himself) who had gone in against great odds to the rescue (from an attack by a gang of Apaches) of two theatregoers, one a visiting tourist, his companion a Parisian and a distinguished doctor. Sadly, the latter had succumbed to a bullet fired by one of the gang, the former was lucky to survive being hurled into the river by his assailants.

This lively scene was, as they spoke, being worked up by an artist into a cover for Le Petit Journal. Under Fourier’s direction, of course, he reassured them. These creatures were attacking in the very heart of the city now! But thanks to the bravery of the aforementioned police officer, two had been shot dead and would trouble the peace of the city island no more. Patrols on the Square du Vert Galant had been doubled.

‘Seems to be paying off, Fourier,’ said Joe. ‘Though I’d have preferred on the whole not to be summoned down to the river on a wild-goose chase on Monday night.’

‘Ah, yes. Clever devils! Some bugger diverted the two agents on duty down there. And rang directly through to my office, someone knowing my number, leaving a message so official-sounding my sergeant passed it straight on. Moulin. He knows . . . knew the numbers, knew the tones that get attention. Probably expected to catch you while you were still up here sitting in front of me.’

He frowned and fiddled with his pen. ‘I can make this sound convincing enough, Sandilands, for general consumption, I mean, on paper. But I can’t make any sense of it –’ he gestured to his head – ‘up here. What in hell did the stupid bugger think he was doing? Clever man. Reliable. Thorough. My best.’

‘Well placed to cover up a whole crime wave of his own creation?’ Joe suggested. ‘You’ll never know now.’

‘And who’s going to take his place? Good Lord! He’s down there on the slab as we speak! I haven’t been to see him yet . . . I don’t suppose . . .? No?’

‘Who’s going to perform the pathology on the pathologist?’

Fourier burst out laughing. ‘Quis medicabitur ipsum medicum?’ he said, surprisingly. He rose to his feet to show Joe to the door.

‘And I’ll add a second thought on similar lines,’ said Joe cheerfully. ‘Who will police the policeman? I’ll tell you – I will!’

In a moment his foot had come out to trip up the Commissaire and his hand simultaneously pushed him hard between the shoulder blades. Fourier’s head banged against the corner of his desk as he went down and he swore in pain and confusion.

‘Bad luck,’ said Joe. ‘You really ought to have that rug tacked down, Fourier. There was a loose end there somewhere, I think.’

‘Poor old thing! You look jolly peaky still,’ said Heather Watkins, pouring out a cup of tea for Joe at Fauchon’s. ‘But I can’t understand why that woman would do such a thing . . . I mean . . . Well, I can just about see why she would undertake . . . um . . . the profession she undertook . . .’ Heather blushed and hunted about for the milk jug. ‘But how could she have let herself be led into a life of crime by that appalling villain?’

‘I think what she gave me and Bonnefoye was a true bill. Ninety per cent of it. The client who insinuated himself into her establishment probably had some strong hold over her . . . blackmail . . . contrived involvement in one of his early excursions . . . I think he took over her life like a cancer, eating it away. He was using her girls as agents in his schemes. Alice was left only nominally in charge and beginning to realize she was herself replaceable. Good liars tell the truth as far as they possibly can and slip in one big falsehood. She told us truthfully what happened – just gave us the wrong name. Picked an entirely innocent Englishman, knowing he would be able to talk his way out of it – and anyway, Jack Pollock was safe enough behind the walls of the Embassy. The worst thing that could have happened to him in the event of an enquiry was a rap on the knuckles from Her Excellency! And a suspension from opera escort duties. But I believe Alice was truly alarmed by the sadistic nature of the man she found herself tied to. By his complete ruthlessness. It defies explanation, Heather! A professional man, clever, sharp, kind to me when in role. And the other side of him, dark, greedy and murderous.’

‘But why? I know men murder others for the satisfaction, even enjoyment it can bring them.’ She shuddered. ‘But his victims were not known to him in a personal way. Where was the satisfaction in that?’

‘I think he was a bit mad. Working in that place – it would send any man off the rails. And I believe he sensed this was happening to him. He made an effort to keep the stone walls, dripping with sorrow, at bay. It didn’t work. The corpses kept piling up and he kept on slicing and carving and witnessing the very worst man can do to man.’

‘He lost his sensitivity? Like a knife losing its edge?’

‘I think so. He had been a sensitive man. He enjoyed the theatre and the opera – he had posters and programmes all over his room and, Heather, the strangest thing – I’d noticed a photograph on his desk. A pretty dark girl. Her face was vaguely familiar. I checked his room yesterday – I went to return a book he lent me . . .’ Joe’s turn to shudder. ‘I thought it might be his girlfriend. I asked one of the assistants if they knew who she was. They looked a bit shifty, I thought, but one of them spoke up. “Don’t you know her, sir? That’s Gaby Laforêt. The music hall star. Nuts about her, he was! Went to every show. Used to joke that one day when he’d made his fortune he’d . . . Well, we all need our fantasies, working in a dump like this, don’t we?”’

‘But why would he want you dead, Joe? How did you figure in his fantasies?’

‘He overrated my insight, I think. Thought I was nearer to putting it all together than I actually was. After all – I’d confided in him, shown him my cards, in fact. One professional to another. And if you see your opponent is holding a Royal Flush, you assume he’s going to play it. He never suspected that I hadn’t recognized the significance of what I had. So – I had to be eliminated. And – possibly as his grande finale – he couldn’t resist stepping on stage himself for a change. I think no one paid him for that display on the bridge. He treated himself to a private performance. He fancied himself as Louis XIV perhaps, that ardent supporter of the theatre, the Sun King, strolling on in the final scene.’

‘Horrid notion! All the same, it’s doubly depressing to think that a man got his thrills by carrying out another fellow’s fantasies! I expect the money was the more important element, you know. But, there, you survived! And so did Jean-Philippe. That’s all that matters. Is he back at work again?’

‘Oh, no. He’s been given a week’s leave. But he’s back at home, firing on all cylinders, driving his mother to distraction. Claims he’s fully fit and she must stop fussing over him. She’s given up on him and decided to go and spend a few days with her sister in Burgundy. George went back to the Bristol to put up his feet for a bit, get his heart rate down and then start on his packing.’

‘Poor soul! Has he had enough of France then?’

‘Not a bit of it! He’s bought a first class ticket on Friday’s Blue Train to Nice. The overnight express. Paris seems to have lost its charm but he’s not quite in the mood for Surrey yet. I think his cousin has cause for concern there! George is showing every sign of going off the rails as soon as he can get up the right speed. He’s booked himself in at the Negresco! Best food in the world, he tells me. And I’m dug in again at the Ambassador for the next day or two. Lively scene! I say, Heather, they’ve got a dinner dance and jazz band on tonight if you’d be interested?’

‘Oh, Joe, I have to leave on Friday – that’s tomorrow! – for the Riviera myself. First game of the tournament on Sunday morning. Must be fresh for that. So, if you can guarantee you won’t step too heavily on my feet and break a toe or try to get me drunk – yes, I’d love to! And then you can wave me goodbye on Friday – I’m on the same train as Sir George. Joe, why don’t you try to get a few days off and come down and watch me play? You look as though you could do with a bit of southern sun . . .’

The Gare de Lyon was bustling with smartly dressed travellers, porters hurrying along behind carts piled high with luggage. Trains whistled and panted and whooped. Joe and Bonnefoye struggled with Heather Watkins’ hand luggage and packages, hunting for her compartment. Finally settled, she leaned out of the window to talk to them.

‘Well, here we are . . . Oh, good grief! Joe! Jean-Philippe! Do you see who that is – down there, thirty yards off, just getting in. Crikey! Shall we pretend we haven’t seen them?’

Joe looked along the train, puzzled. ‘George! It’s George! I said goodbye to him this afternoon at the hotel . . . I don’t need to show my grinning face again.’

‘The last thing he’d want to see at this moment, I think,’ said Heather mysteriously. ‘Look! He’s with a woman.’

Bonnefoye saw her at the same moment. With one hand she picked up the hem of her dark blue evening cape and with the other grasped the hand of Sir George standing gallantly at her side. Laughing, she stepped nimbly up into the train, turned and pulled him up after her into her arms.

‘They’ve gone into a sleeping compartment,’ said Bonnefoye, astonished.

‘That’s what people do on the Blue Train,’ said Heather, giggling. ‘What fun! How smart! She’s very pretty! And – I have to say – what a lucky lady!’

‘That was no lady – that was my mother!’ spluttered Bonnefoye. ‘What the hell! Visiting my aunt Marie indeed! And she has the nerve to go off wearing my birthday present.’

‘Glad to see it got there on time,’ said Joe, smiling.

‘It was you, wasn’t it?’ Bonnefoye rounded on Joe. ‘Duplicitous fiend! It arrived with a card – Amélie, with eternal gratitude from an English Gentleman. She thought it was from George!’

‘If he’d been aware, I’m sure it would have been,’ said Joe. ‘I didn’t quite like to disillusion her. Delphine in the rue de la Paix was very understanding when I nipped in with my cheque book and a disarmingly salacious story. Let’s hope they’re as understanding at Scotland Yard when I present them with my expenses! So that’s what you earn in a month, Jean-Philippe? You’re really doing rather well, aren’t you?’