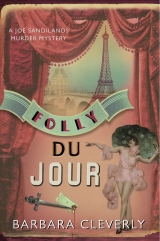

Текст книги "Folly Du Jour"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Chapter Eight

As they approached the hotel, George became increasingly agitated. In his hatless, beaten-up state he had been receiving some questioning looks from the smartly turned-out inhabitants. One lady had even crossed the road to avoid encountering him.

‘I say, you chaps,’ he said fifty yards short of the Bristol, ‘better for everyone if I don’t cross the foyer looking like this. I’d be an embarrassment to the management as well as to myself. There’s a side alleyway they use for deliveries to the kitchens. I’ll use that. I know my way about. I’ll nip up in the service lift. See you in my room. That’s 205.’

He would listen to no argument and slipped away without a further word.

Joe and Bonnefoye pressed on to the Bristol and requested the key. Bonnefoye produced his badge and asked the maître d’hôtel to summon a doctor and send him up with the utmost discretion.

Once over the threshold of his own room, George rallied and tried again to dismiss his attendants. ‘No need to wait on me, you chaps. No need at all. I can manage. I’ll see the medic if he appears, for form’s sake, but – really – no need of him. Let’s keep the fuss to a minimum, shall we?’

‘No khitmutgars here,’ said Joe cheerfully, pushing past him into the room. ‘Not even a valet. You’ll have to make do with us. Jean-Philippe – run a bath, will you, while I hunt out his pyjamas and dressing gown. Is this what you’re using, George? This extravagantly oriental number? Good Lord! Now, just sit down will you, old chap . . . you’re teetering again . . . and you can start peeling off that disgusting vest.’

Bonnefoye returned from the bathroom lightly scented with lavender to catch sight of Sir George in his underpants, slipping a purple silk dressing gown around his shoulders. He stood still and exchanged a startled look with Joe. When George had disappeared into the bathroom he hissed: ‘Sandilands! That mess on his back! Scars? Weals? What in hell was it?’

Joe was recovering from his own astonishment at the brief glimpse he had caught. ‘Good Lord! It seems I wasn’t exaggerating. I was just retelling an old story that does the rounds in India. I had no idea it was accurate.’

‘Tough old bird,’ murmured Bonnefoye. ‘Fourier had no idea what he’d run into.’ And then: ‘He never would have signed a confession, would he?’

‘No,’ said Joe. ‘But that doesn’t mean he has nothing to confess. There’s something wrong with all this. He’s hardly begun to explain what he’s involved in. I think he’s been lying to the Chief Inspector but, if he has, there’ll be a damned good reason for it. Fourier couldn’t beat the truth out of him and we, my friend, must use other methods. As soon as we’ve got him settled I’m going back to the morgue to take a look at the man at the bottom of all this – our mystery man, Somerton. No – no need to come with me – I’ll report back. You should go back to your duties, Jean-Philippe – I’ve taken up too much of your time already.’

‘No one will notice. I was given a couple of days to prepare for the conference. Unfortunately, I can’t get out of that and I’ll have to turn up and show my boss my grinning face, I’m afraid. You can telephone me at the number you have at any time – if I’m not there someone will take a message. It’s pretty central . . . Left Bank . . . nothing very special but my mother’s happy there. The rue Mouffetard – do you know it?’

Joe knew it. A winding medieval street of old houses, market stalls, cafés and student lodgings, one of the few to escape the modernizing hand of the Baron Haussman.

‘Just south-east of the Sorbonne? Near the place de la Contrescarpe?’

‘Exactly. You need the place Monge Métro exit. Let me write the address on the back of the card I gave you.’

Joe was amused. ‘You don’t give out your address to all and sundry?’

‘Matter of security,’ said Bonnefoye. ‘Mine!’

‘You have an apartment?’ Joe asked.

‘No. It’s my mother’s apartment. On my salary it will be some time before I can afford to rent one of my own. You have to pay fifteen thousand francs a year for a decent place in Paris. It’s the foreign invasion that’s put up prices.’

‘Invasion? You’d call the tourist influx an invasion, would you?’

‘Hardly tourists! Ten thousand semi-permanent residents have flooded in, mostly American, some British, all keen to take advantage of what they consider the low prices in France and all able to pay more than an ordinary copper for a decent place. Do you know how I’ve spent my time, this last month? Sorting out cases of grievous bodily harm and damage to property on the Left Bank. The indigènes of Montparnasse have started to show their resentment of the way the Yanks have taken over whole quartiers. They don’t like the way they buy up cafés and turn them into cocktail bars, they don’t like the food they consume or the way they consume it . . . they don’t like their loud voices . . . they don’t like the way they look at their girls . . . You know the sort of thing. It’ll only take a spark to blow the lid off. Might try raising that with Interpol.’

The hastily summoned doctor examined Sir George and passed him as perfectly well – suffering from shock, naturally, as one would, being the victim of a street robbery – and from the obvious contusions but otherwise nothing to be concerned about . . . Nothing broken. No – a very fit specimen for a man of his age, was the reassuring verdict. All the same, the doctor grumbled, attacks like this were growing more frequent. And on the Grands Boulevards now? Tourists to blame, of course. A honey pot. Too easy and tempting a target for the local villains. It was quite disgraceful that a respectable gent like the patient couldn’t return from the theatre to his hotel along the most civilized street in the world without being beaten up. Where was the police presence in all this, the good doctor wanted to know.

A complete rest with plenty of sleep was his prescription. Of course, there was always the danger at any age of a delayed reaction to a head wound. Was there someone they could summon to sit with him . . . just in case . . . a compatriot perhaps would be most suitable in the circumstances. He left his card and took his leave.

‘A nurse?’ Joe, eager to dash off to the morgue was impatient at the doctor’s request. ‘Is that what he’s suggesting? Where on earth do we dig up a nurse at a moment’s notice?’

Bonnefoye grinned. ‘This you can leave to me, Joe. I think I can work my way around the problem.’ He took out a small black notebook and began to flip through the pages. ‘You go off and interrogate the corpse. You’ll find all well when you get back.’

On the ground floor a lean-faced man in his mid-thirties, unremarkable in sober city clothes, was waiting for a friend. He watched Joe step out of the lift, cross the lobby and greet the doorman. He looked at his watch, shrugged and decided to abandon his assignation. Following Joe outside, he stood patiently by, next in line. He heard Joe speak to the driver of the cab: ‘Ile de la Cité. Institut Médico-Légal.’ The man smiled and walked back into the lobby.

Joe was admitted with courtesy into the Institut. Sombre, forbidding and dank, the building was everything Joe expected of a morgue and forensic pathology department combined. He was going to have to return in the evening escorting Somerton’s widow and he wanted to be certain that he could find his way about, to be prepared to answer any questions she might have. The usual run of grieving relatives tended not, on first confrontation with the corpse, to be particularly searching with their queries. A combination of feelings of loss and the oppressive atmosphere of the viewing room was enough to reduce them to an inarticulate silence, a nod or a shake of the head or, at best, a few muttered words, most frequently: ‘Did he (or she) suffer?’

Somerton certainly suffered. But not for long, Joe estimated, staring down at his corpse. The pathologist in charge of the case who had officiated at midnight the night before had returned, he now told Joe, straight after breakfast to continue his examination. Le docteur Moulin was wearing the white overall, cap and gloves of a surgeon and was as cheerful as the depressing circumstances allowed. His intelligent brown eyes were the only source of warmth in the whole building, Joe thought. He was expecting Joe and looked only briefly at his identification before leading him past three other livid corpses laid out in a row to a marble-topped, channelled table where the body of the Englishman was laid out.

‘Were you gentlemen acquainted?’ asked the doctor, extending a hand to Somerton.

‘Not in the slightest. I’m here to investigate, not identify. He has been named by the man who discovered the body and his papers confirm his identity. The widow, Lady Somerton, is on her way and will attend this evening to sign any documents you may present. Before she turns up, I’d like to familiarize myself with the details, so that I can guide her through it, if you have enough to go on . . .’

‘Oh, yes. More to do, of course, but peripheral to the police enquiry, I’d say. I shall be obtaining a toxicology report, checking stomach contents – the usual – but the cause of death I think you’d agree is pretty obvious.’

Joe stared with pursed lips at the body laid out on the slab. He was struck by the way in which the hair and moustache, retaining their luxuriance and dark colour, were at odds with the waxen flesh from which the humanity seemed to have drained away. What was the dead man telling him? What could he possibly learn from the already decaying features of a man he’d never seen alive, had never heard speaking? Joe recalled a phrase the usherette had used in her statement: ‘Visage de fouine.’ Weasel-faced. Yes, he could see why she might say that. The sharp nose and chin in a narrow face offered a contrast with George’s broad and handsome features. The expression and animation of the living man would also most probably have coloured the girl’s impression of him and on this Joe would never be able to form an opinion. The eyes were closed, the thin, well-shaped lips set in a tight line.

The five franc tip, Joe remembered. What a frightful epitaph!

The knife slash that had killed him went from ear to ear. Cleaned and closed, it was still a fearsome sight. Joe could only imagine the shattering effect on George of discovering his friend – dead? dying? – with blood pumping by the pint from the gaping wound.

‘Have you any views on how the wound was administered?’ Joe asked.

‘I have. Dealt from behind, I’d say. I understand the victim was watching a performance at the Folies? In a box either by himself or accompanied by a young lady? A question for the police to clear up. Obviously, if she were sitting or standing next to him the lady would be drenched in blood. When she went to the vestiaire to retrieve her coat, someone would have noticed her state.’

‘He’s quite a tall man, the victim?’

‘About five feet ten inches and, though he must be in his mid-fifties, his musculature is in good condition.’

‘Difficult to subdue a man of that height unless you are yourself taller and more powerful, you’re thinking?’

‘As are you, Commander. He’s hardly likely to oblige by standing there, sticking out his chin and closing his eyes! A man like this would have fought back against a perceived assailant.’ The pathologist pointed to the hands and forearms. ‘No signs of wounds received during self-defence, you see. No attempt to repel a knifeman. It’s my theory that his attacker came up behind him while he was still seated, seized him – possibly left hand over his mouth – and slashed and sawed his throat from ear to ear. Standing behind your victim, you would not be showered by his blood which would be projected out and down. You then allow the body to flop forward on to the padded edge of the booth where the obliging upholstery absorbs most of the litres of blood. Velvet, quilted over cotton wadding, I understand.’

‘And if you’re a careful killer,’ added Joe, ‘and I’m sure our man was just that, you’d have taken off your opera cloak and put it on the peg by the door, murdered your victim and then put your concealing cloak on again before leaving. If you’ve timed it just right, your exit will coincide with the moment everyone was streaming out of the theatre.’ He knew that moment. Everyone preoccupied with his or her own immediate plans . . . taxis, supper, romance. No one wanted to catch the eye of a stranger in the crowd.

Joe went to fetch a chair, placed it at the foot of the marble slab and sat down on it. ‘Doctor, would you mime the action of the killer as you judge it to have been carried out? I’ll be the victim.’

‘Of course. And, in the pursuit of authenticity – a moment – I’ll just fetch the weapon.’

Moulin bustled away into his office, returning with a cardboard box filled with material conserved from the corpse. ‘We’re holding all this until the police and the magistrate are satisfied. You know the routine?’ He waited for Joe’s nod and went on: ‘The personal effects will be returned to the next of kin. Not sure they’ll want to keep this as a souvenir though,’ he said, producing from a paper bag a dagger with an eight-inch blade and a carved ivory hilt.

‘I’d like the lady to take a look, if she can bear it,’ Joe said. ‘Just in case she can identify it as her husband’s own property.’

‘You can take hold of it,’ said Moulin, offering it by the point of the blade. ‘It’s been tested for fingerprints and cleaned up. No prints, by the way. It had been wiped clean – just some unusable smears left.’

Joe took the object with distaste. ‘Afghan.’ He turned the blade flat and slid it over the back of his hand, slicing through a few hairs. ‘Sharp as a razor.’

‘It would need to be to go quickly through such an amount of muscle and gristle. The throat is not an easy option. But it is quick and sure. Think of pig-killing. In my village they always go for the throat. And a pig’s flesh has more or less the same density and resilience as a man’s. This knife went upstairs to the laboratory for inspection. Under the microscope you can see the signs of the use of a sharpening implement on the blade. Very recent sharpening was done. Perhaps with the killing in mind?’

‘Ah? A workmanlike tool. Not a cheap blade but not lavishly produced for display, I’d say. It’s not as ornate as many I’ve seen. An inch or so shorter than most. Discreet. An efficient killing blade.’

‘Indeed. Now this is what I think happened. For the record – I’m five foot eight inches tall, so we’re possibly looking for someone two to four inches taller. And almost certainly more powerfully built.’ The doctor took the knife in his right hand. He mimed taking off his cloak and hanging it up then he moved silently behind Joe who leaned slightly forward in the attitude of someone engrossed in the performance on the stage below.

‘Ah! In the dark and with your head tilted forward like that it’s not so easy to get a hand around your mouth. I’m going to change my plan slightly,’ said Moulin.

He grasped Joe by the hair and pulled his head back, applying the dagger blade to his exposed throat. Joe could not repress a shudder as the cold steel gently touched the skin behind his left ear.

‘Yes, that’s how it would have been done!’

‘What about the noise, doctor? Would he have had time to let out a scream?’

‘Oh yes. Think of any pig you’ve ever heard being slaughtered. They manage a few seconds of hideous squealing before their voice box is cut. It must have been done at a moment of intense surrounding noise.’

‘I agree. The finale?’

‘Yes. Clapping and cheering and, these days, with such a large foreign element in the audience, you tend to hear whistles and squeals of a very un-French nature. And that theatre is the largest in Paris. There must have been close on two thousand people creating a din. Now, if his companion for the evening had been there during the murder she would have been an accomplice or – if a witness – would have been, I presume, made off with – eliminated? – by the guilty party. In some other place, at some other time, as there were no signs of further violence in the box, I understand. I would fear for the young lady’s safety, wouldn’t you?’

‘Accomplice? Witness? Not necessarily,’ said Joe. ‘She might have been the killer. What would you say?’

‘A woman?’ The doctor was taken aback. ‘Physically it’s certainly possible, I suppose . . . if she approached him from behind as I’ve demonstrated. You’d need a considerable rush of energy – determination, hatred . . .’ His voice tailed off doubtfully.

‘You don’t like the theory?’

Moulin smiled. ‘No more than I observe you do, Commander! We both know this is not a woman’s method.’

‘True. In my experience, when women plan a murder – and from whatever rank of society they come – they choose more subtle methods. Poison and the like. Anything from rat poison to laudanum. When the killing is done on the spot and the result of an overriding urge, or a desperate attempt at self-protection, they use the nearest weapon to hand – usually a domestic tool which, depending on their circumstances, may be a frying pan . . . a silver sconce . . .’

‘Contents of a theatre box not much use, I’d have thought. Could you throttle someone with all that gold braid?’

‘I wouldn’t want to try it. No. Someone chose to take this dagger into the box and use it. And leave it behind for all to see. This particular dagger. It’s distinctive. Meaningful. Personal, I’d say. The victim had fought in Afghanstan, his fellow soldier tells me. There’s a possibility that it may be from his own collection. Carried there by the victim himself and turned against him in an unpremeditated attack?’ Joe sighed. ‘Much work to be done yet, I’m afraid.’

Rising from his chair, Joe was struck by a sudden thought. He walked over to the corpse and lowered his head to sniff the improbably dark hair. He looked up and said: ‘Pomade?’

Moulin joined him and repeated the process. ‘Certainly,’ he agreed. He sniffed again. ‘Unpleasant. Not French. Much too heavy. I’d say something like Bay Rum, wouldn’t you? And it’s sticky.’ He took off a glove and tested a strand of hair between thumb and forefinger.

Joe did the same. He peered at the crown of the man’s head. ‘Well-barbered hair though a little long for most tastes, I’d have thought. Plentiful and would give a very good grip to anyone choosing to sink his fingers into it. As you demonstrated. Left parting and – look – it’s disordered on top. Could have happened involuntarily at any moment after the death of course, during the manhandling of the body by the authorities. But if your theory’s right, doctor, the killer must have had a disgustingly sticky left hand – and not sticky with blood. It’s not much but . . .’

He accepted Moulin’s offer of soap and water and towel in a side room and they washed their hands in a companionable silence together, each deep in thought. ‘I thank you for working through all this with me, doctor,’ Joe said, walking back to pick up his briefcase. He hesitated and then made up his mind to ask: ‘Shall I hope to see you later on today when I bring the widow Somerton? Or will you have handed over to a colleague by then?’

Moulin smiled. ‘I shall arrange to be here, Commander. More dead than alive myself by that hour but . . .’ He shrugged. ‘You’ll find me here. I’m very bad about delegating. Particularly when a case has caught my attention as this one has.’

Emerging from the depths of the stone Palais de Justice building, Joe experienced again a rush of relief and pleasure. He took a minute or two to raise his face to the sun, to breathe in the not-unpleasant river smell, to be thankful that he wasn’t laid out on a slab or filed away in one of the steel drawers that lined the walls. He’d taken a liking to Moulin – an admirable man, professional but not stuffy. A brother. But he did wonder how he managed to stay sane working in that chill, haunted place. Above all he asked himself how bearable would be the claustrophobic effect of those thick walls on a recently widowed Home Counties lady. He looked at his watch and calculated that she was in mid-air over the Channel, delicately refusing the oysters most probably.

Lunch! Suddenly hungry, Joe decided to make for a café and find something he could eat within half an hour. The place St Michel was just over the river. Food over there on the Left Bank was cheap and quickly prepared. The were mostly students and Joe enjoyed the informality, the laughter and the sharp comments he heard all around him. He settled at a pavement table on the square and decided to order a croque-monsieur. Always delicious and quick to produce. He wondered what to drink with it and thought his usual beer might finally send him to sleep. A bottle of Badoit or a plain soda water might be more –

Soda! Campari-soda! The shock of realization was so intense he looked furtively around him to see if anyone was conscious of his reaction to the sudden thought. Ridiculous! These chattering strangers, even if they’d been looking in his direction, wouldn’t have given a damn for an Englishman whose startled expression was that of a man who’d just remembered – too late – his wife’s birthday.

‘Campari-soda’! George had been trying to pass on a message and he’d missed it. Pink and decadent, light but lethal. And always, for him, to be associated with that woman.

George had been attempting to let him know he’d spent the evening trapped in a box with a viper.

Joe, all appetite vanished, chewed his way through his sandwich and planned his next move. Looking around him, he remembered that he was just a few steps away from the rue Jacob and he frowned.

Good Lord! It seemed a week ago he’d met that redhead on the plane. What was her name? Heather, that was it. And she was staying at a small hotel down there. Raking his memory, he had a clear impression he’d promised to meet her again, though he’d left it all a little vague. He doubted she was the kind of girl to sit in her room waiting for him to contact her but, all the same, it would be too rude to do nothing. He could at least explain that he’d run head-first into the most frightful bit of trouble and wouldn’t be at liberty to enjoy Paris with her as he’d hoped. Paying his bill, Joe strode off down the rue St André des Arts and crossed over into the rue Jacob. He wandered along until he found a pretty, flower-bedecked hotel whose name rang a bell.

The receptionist at the Hotel Lutèce admitted he had a guest of that name but Mademoiselle Watkins had gone out over an hour ago and – no – she had not said at what time she expected to return. With some relief, Joe scribbled a note and left it in her pigeon-hole.

And now, he was free to concentrate on a second lady who’d caught his attention. He took out his notebook and checked the address he’d hurriedly memorized from the Chief Inspector’s interview sheets and copied down later. An address in Montmartre. He looked up and north, seeking but not finding, for the press of rooftops, the gleaming white dome of the Sacré Coeur, presiding over the huddle of cottages, mills and cabarets that made up the old village on the hilltop. Too far to walk in the time he had. Joe went back to the place St Michel and picked up a taxi.

‘Montmartre. La rue St Rustique,’ he said. ‘Le numéro 78.’

‘Another liar!’ he thought and began to plan how best he could lay a trap for her.