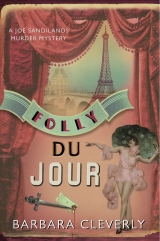

Текст книги "Folly Du Jour"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

‘I say! However did you know I was there? Clever of you to find me! I shall have to hope my wife is less vigilant than the French police, eh? What? I read about this sorry affair in the papers. Fellow Englishman knifed to death, they’re saying. And that’s the extent of my knowledge, I’m afraid. I’ve never met the dead fellow. I was in the stalls. Thought you might like to see my ticket stub.’

Fourier looked carefully at the number on the ticket. He took a pencil and a sheet of paper and in a few quick strokes sketched out a floor plan of the theatre. He placed it on the desk in front of Jennings. ‘Can you confirm you were sitting where I have marked an X?’

‘Yes. You’ve got it exactly!’ said Jennings. ‘I say – you know your way about, Chief Inspector! A regular yourself at the Folies, are you then?’

Joe didn’t attempt a translation.

‘I now add two boxes,’ said Fourier, supplying them. ‘Take my pencil and mark in the box where you understand the murder to have taken place.’

Jennings obliged.

‘Well done! Quite correct! Box B.’ Fourier’s attempt at bonhomie was unconvincing. ‘Now, tell us who and what you observed in that box.’

Jennings’ account was disappointing. He was quite obviously doing his best but his best was not pleasing Fourier. An unknown man (dark-haired), an unknown girl (fair-haired), had been noted before the lights went out and again when the lights came on again in the interval. Between and after those times – nothing of interest.

‘Of course, had one only known, one would have . . .’ Jennings burbled. ‘Tell you what, though! Why don’t you ask the chap opposite? May I?’ He took the pencil again and marked Box A. ‘Now, if you can find me, I’m jolly certain you can find him. He had a perfect view of the deceased. And he knew him,’ he announced.

‘And I understand the witness in Box A was known to you also?’ said Fourier with mild interest.

‘I say! This is impressive! Yes, he is known to me. Only seen him once or twice since we were at school together – reunions and so on – but there’s no mistaking that nose. Jardine. It was George Jardine. I’ll bet my boots. Something important in India, I believe. Showing off as usual. In the Royal Box. But where else? Wouldn’t find him rubbing shoulders with hoi polloi in the stalls.’

‘And you think he was acquainted with the man opposite?’

‘Oh, yes. Undoubtedly. They were talking to each other.’

Fourier stirred uneasily. ‘Across the width of the theatre, sir? Talking?’ His strong witness was showing signs of cracking. He looked to Joe to correct his interpretation but Joe shook his head.

‘“Communicating”, I ought perhaps to have said. Exchanging messages. Just the sort of showy-off Boy Scout stuff Jardine would have indulged in. He always enjoyed an audience, you know. Incapable of fastening his shoelaces without turning round to acknowledge the plaudits of the crowd.’

Joe summarized this and added, ‘Fourier, may I?’

Fourier spread his hands, amused to delegate.

‘Would you mind, Jennings, demonstrating the form this communication took?’

‘Certainly. As the lights were being lowered . . .’ Jennings got to his feet and went to stand, back to the wall, looking down at an imagined audience. His face froze in a parody of George’s lordly style. ‘He put on his white gloves . . .’

On went the gloves.

‘And then he did this sort of tick-tack nonsense with his hands.’

The hands flashed rhythmically, fingers stabbed, thumbs were extended.

‘You’d have thought he was leading the Black and White Minstrels in the show at the end of the pier. People were beginning to think he was the first act.’

‘And did the man opposite take any notice? Did he reply?’

‘Yes. Same sort of thing but a shorter response and he wasn’t wearing gloves so it wasn’t so obvious. I thought, at that moment, it was a game. Yes, I was sure it was a game. He was laughing, joining in the fun.’

‘You thought?’ asked Joe, picking up the tense.

‘Yes. Changed my mind when I saw the last gesture though!’

‘Describe it,’ said Fourier.

‘He did this,’ said Jennings.

Face twisted into a threatening mask, he gave a flourish of the hand and trailed the forefinger slowly across his throat.

No one spoke. The sergeant stopped writing. Fourier turned to him and advised: ‘Sergeant, why don’t you put down – “The suspect was observed at this point to make a life-threatening gesture announcing his intention of cutting the victim’s throat.”?’

The sergeant noted it down.

Jennings knew enough French to take alarm at the twist Fourier had put on his words. ‘Look here! That’s a bit strong, don’t you know! Sandilands, put him right! I wasn’t implying that . . . Oh, Good Lord! He wasn’t in my House but I didn’t come here to drop old Jardine in the quagmire . . .’

‘Did you not?’ drawled Joe. ‘Well, you’ve made a very good fist of it. But before we ask you to check and sign your statement, just tell us, will you – what was the reaction of the second man playing this game? Did he appear alarmed? Did he seem menaced by Jardine’s gesture?’

‘Well, no. Not at all. Most odd. He laughed. Damn near slapped his thigh, he thought it was so funny.’

* * *

When Jennings had been thanked and escorted from the premises by the sergeant, Fourier turned to Joe and Bonnefoye with a pitying smile. ‘The case firms up, it seems,’ he said. ‘And unless you two are about to produce some late entrant like a jack-in-the-box to surprise me . . .’ He left a pause long enough to annoy the younger men. ‘No? Well, there is one more amusing little excursion I’ve laid on for you.’

He gestured to his sketch of the theatre layout. ‘Forget the audience. What no one else seems to have observed is that there were a hundred or so other potential witnesses and all much closer to the scene of the murder at the moment of the murder. The cast! Lined up for the finale, their eyes would have been on their audience. They say that Miss Baker herself is always acutely aware of the reactions of the crowd before her and responds to their mood. Dark, of course, out there, I should imagine. Up to you to see how much you can make out. How close the boxes are to the stage. Which performer was standing underneath.

‘I’ve arranged with the man in charge – Derval’s his name, Paul Derval – for you to be given an hour to scrounge around before the matinée performance this afternoon. I guaranteed you wouldn’t get in anyone’s way. He’ll send someone to open up for you if you present yourselves at the stage door. That’s about it . . . Jardine behaving himself, is he?’

He started to collect up his papers. As they reached the door he said: ‘Oh, I fixed a ten-minute interview for you with Mademoiselle Baker. Thought you’d make a better impression on her than I would. She wants to help, apparently. Tender-hearted girl – keeps a menagerie of fluffy animals in her dressing room backstage, I’m told. She was upset to hear some admirer had bled to death while she was singing her heart out a few metres away. See what you can do.

‘We may be getting closer to that headline,’ he added with a chuckle they left.

Chapter Eighteen

‘Some time to kill before our two o’clock tryst in the avenue Montaigne.’ Joe emerged with relief into the sunshine. ‘The theatre’s not all that far from my hotel . . . Why don’t I take you to lunch there first – Pollock assures me the cuisine is excellent. And I think we’ve earned it! But first – a short walk. What is it about this place –’ he stabbed a thumb backwards over his shoulder – ‘that makes me want to burst out and run ten miles in the fresh air?’

‘Fourier?’ grunted Bonnefoye. ‘Medieval architecture . . . medieval mind? Know what you mean, though. Which direction do you want to take? I’ll gladly trot alongside.’

‘Let’s cross over into the Tuileries, cut through the gardens and make for the place Vendôme.’

‘Why would we want to do that?’

‘Off the place Vendôme, running north towards the Opéra, we’ll find the rue de la Paix. Not a street I’ve frequented much. Wall to wall with modistes, I’m told.’

He took Francine’s scrap of blue fabric from his inside pocket. ‘Well, you never know. This is from the House of Cresson, according to Mademoiselle Raissac. It’s a lead we ought to follow up. It may take us to the beauty who showed a clean pair of heels before the show ended. Think of it as Cinderella’s slipper, shall we?’

‘Not we, Sandilands. They would be instantly suspicious of two men arriving with a strange enquiry.’ He looked at Joe then tweaked the sample from his fingers. ‘I’ll deal with this. You can loiter outside, window shopping. I suggest the jeweller’s. That’s safe enough. You’re choosing a ring for your girlfriend.’

It took a considerable amount of confidence to put on a routine such as Bonnefoye was demonstrating, Joe thought, in this smartest, most exclusive of streets. There were men to be seen entering the salons but they followed, dragging their heels, in the slipstream of their smartly dressed wives. Their role was clear: parked in a little gilt chair, they were required to smile and admire everything they were shown until, finally catching a nod and a wink from the vendeuse, they would come to a decision and pull out their wallets. The solo flight Bonnefoye was contemplating was daring. Professional, well-disciplined and having the sole aim of charming large sums of money from rich and fashionable women, the elegant assistants Joe caught glimpses of through the windows were truly daunting. They moved about with the easy arrogance of priestesses tending some vital flame.

Bonnefoye looked smart enough – he wore his good clothes well – but he would be entering hostile territory. He watched the young Inspector’s reflection in a shop window opposite the gold and black façade of Maison Cresson as he straightened his tie, tilted his straw boater to a less rakish angle and strolled inside, humming an air from Così fan tutte.

He was in there a very long time, Joe thought suspiciously. He saw Bonnefoye emerge finally, scribbling on a page of his little black book. He slipped it away into his breast pocket. Joe sighed. An address had been added to his list. But whose?

‘Another success, Inspector?’ he asked. ‘How did you manage it?’

‘Two successes!’ Bonnefoye gave a parody of his best slanting Ronald Coleman smile to indicate method. ‘But the one that concerns you, my friend, is the identification of the fabric. It wasn’t easy. Sacrifices had to be made! There’s a good café just around the corner. Why don’t we walk on and have our second coffee of the day?’

They moved off out of the sight lines of the salon.

‘A charming girl greeted me . . . Delphine . . . I told her I was desperate. I wished to buy something special for my mother – for her birthday. And the trouble with rich spoiled old ladies . . . I was quite certain Mademoiselle Delphine would understand . . . was that they had everything. I had noted (sensitive son that I am!) on a recent visit to the theatre that she had been very taken with a certain evening cape being worn by a blonde young lady. I produced the swatch at this point. A dear friend of mine – the Comtesse de Beaufort – had advised me that such a garment might be found at the Maison Cresson.’

‘A moment, Bonnefoye . . . the Countess? You’ve lost me! Who’s this? Does she exist?’

‘Of course. And I know the lady to be a devoted patron of this establishment – Cresson labels right down to her silk knickers! I arrested her husband two months ago for beating a manservant nearly to death. The Countess was duly grateful for the brute’s temporary removal from the family home. And the suggestion of intimacy with a valued customer impressed Delphine. She was very helpful. She identified your scrap – though claims the stuff they use to be of better quality. Twice the weight and a richer dye, apparently. She remembered the garment for a very particular reason. They had designed and sold no fewer than four as a job lot, a highly unusual procedure, and all in the same size and fabric. The capes had been commissioned by a certain customer with whom they do a good deal of business. To reproduce a copy for my mother, it would be only polite to seek permission, of course.’

‘Understandable. The thought of five examples of a designer piece out and about in Paris would horrify your Delphine. Suppose the ladies all chose to wear it at the same occasion? The reputation of the House for exclusivity would be ruined! Have you noticed, Bonnefoye, that we men all try to look alike, toe the fashion line, cringe at the thought of looking different, but a woman would die rather than be seen in the same get-up as one of her friends?’

‘Exactly! So why on earth would they want so many cloaks? Not kitting out a nunnery, do you suppose?’

Bonnefoye produced his book again and flipped it open. ‘Delphine was very happy to undertake the negotiations on my behalf. I’m certain she didn’t take me for an haute couture pirate or anything of that nature but, all the same, the training prevailed. No address was forthcoming, I’m afraid.’ He grimaced. ‘And I even went to the length of ordering one of those things. There on the spot! I heard myself selecting twilight blue silk. Grosgrain. Lined with pigeon’s-breast grey.’

‘Shantung?’

‘Of course. Have you any idea of the cost? A month’s pay! But I thought I ought to underline the urgency. Birthday next Thursday, I said. It seemed to work!’

‘That – or the appeal in your spaniel’s eyes, liquid with filial affection?’ said Joe.

‘We have a saying – A good son makes a good husband. Perhaps that’s what Delphine was thinking? But whatever it was, it did the trick. She swayed over to the telephone and asked for a number. I memorized it.’

They settled at a café table outside on the terrace and ordered coffee.

‘The temptation,’ said Joe, ‘of course, is to nip straight inside and use their phone. See who answers . . . but . . .’

‘We could do that. I have ways of tricking identities out of people who answer their telephones. Ordinary, innocent people, still slightly bemused by the new device on their hall tables. I wouldn’t expect any success if we’re dealing with a criminal organization. And if I mumbled, “Sorry, wrong number,” or “Phone company – just checking,” and cut the connection, it might alert them.’

‘I don’t want to be boring,’ Joe began tentatively, ‘but in London –’

‘And here in Paris!’ said Bonnefoye. ‘We have the same facility. It’s not so exciting as establishing a direct contact with a suspected villain but I’m about to go inside and ring up a department on the fourth floor at the Quai. They hold reverse listings of all the numbers in Paris.’ He took out his book again. ‘Won’t be a moment.’

Joe was drinking his second cup of coffee before Bonnefoye emerged again. In silence he passed the notebook across the table to Joe.

‘Ah! I think we might have been expecting this,’ said Joe, smiling with satisfaction. ‘Let me teach you another London expression, mate: Gotcha!’

Vincent Viviani strode smartly down the avenue Montaigne towards the Pont de l’Alma. He was glad that his schedule had led him back to this part of Paris. He’d make time in his day to go and have a look at his favourite bridge over the Seine. Not being a theatre-goer, there was little to bring him to this increasingly smart area. Like everyone else passing by, he gave a swift, unemphatic glance at the three-storey, art nouveau façade of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. Overblown, sweet-toothed, but perfect for its purpose, he supposed. Offering rich men the chance of parting with large sums of money for the privilege of gawping at acres of jiggling, gyrating female flesh – of all colours now, it seemed. He flicked an interested eye sideways, following the two men on the opposite side of the road. They ducked into the alley that led to the side door of the theatre. Stage-door Johnnies? Yes, they looked the part. At least the boater was a good attempt. Vincent wasn’t sure the grey felt would open many doors.

He pressed on without a break in his stride down towards the bridge. The bridge itself wasn’t much but he’d always been fascinated by the four stone figures that decorated it. Once, when he was a small boy, his father had brought him here and pointed them out. He’d thought that’s what a soldier’s grandson would like to see. He was right. Vincent had been enchanted by the four Second Empire soldiers. The Zouave was his favourite. He stood, left hand on hip, neatly bearded chin raised defiantly against the current, swagger in his baggy trousers, tightly cinched jacket and fez.

His father had been pleased with his reaction. ‘Les Zouaves sont les premiers soldats du monde,’ he’d said. ‘That was the opinion of General St Armaud after the Battle of Alma when we licked the Russians. And your grandfather was one of them. A real Zouave. Not one of the ruffians they recruit from the east of Paris these days – no, he came straight from the mountains of Morocco . . . Kabili tribe. Second regiment, the Jackals of Oran. No finer fighters in the world.’

Vincent had signed on as soon as they would take him. He’d managed to see action in North Africa before the war broke out in Europe. He’d been a seasoned hand-to-hand fighter like the rest of his men, wearing just such a flamboyant uniform. A lieutenant by then, he’d slashed, burned and bayoneted his way through the forests of the Marne at the beginning of the war, realizing that he and his regiment were finished. The red trousers, the twelve-foot-long woollen sash, the red fez all cried, ‘Here I am! Shoot me!’ And the Germans, lying holed up in every village, wasted no opportunity. He’d witnessed the arrival of the British gunners, coming up late to their aid. Not creeping or dashing along – marching as though on the parade ground, camouflaged in their khaki clothing, stern, calm, standing firm when the sky above them was exploding. Machines of war.

And, of course, his regiment had adapted. They’d been kitted out in bleu d’horizon, issued with more suitable weapons. He’d survived until Verdun. He’d been there at the storming of the fort of Douaumont. He’d been collected, one of a pile of bodies, and sorted out at the last minute by an orderly more dead than alive himself, into the hospital cart instead of the burial wagon. Months later, he’d come back to his old mother in Paris and she’d seen him through the worst of it. And he was flourishing. Not for Vincent a nightly billet under a bridge with the other drunken old lags. He had his pride and as soon as he had his strength back he’d got himself a job. It had taken a stroke of luck to get him going but he was in full-time employment. Employment that demanded all his energy and used all his skills. What more could a retired soldier ask? The pay was better than good, too, and his mother appreciated that. She had a fine new apartment. When he’d told her he was in the meat industry, she’d not been impressed but she’d accepted it. Something in Les Halles – a manager in the transport section – she told her friends. Out at all times of night, of course. She didn’t know he was still soldiering.

He smiled and strolled the few metres down to the place de l’Alma where he greeted the old lady keeping her flower stall by the entrance to the Métro. He spent a few rare moments idling. Paris. He never took it for granted. After the grey years of mud and pain, the simplest things could please him. The walnut-wrinkled face and crouched figure of the flower seller, surrounded by her lilies and roses, beyond her the glinting river and the Eiffel Tower, so close you could put out a hand and scratch yourself on its rust-coloured struts, this was pleasing him.

His smile widened. He’d buy some flowers. And he knew exactly which ones to choose.

‘Two inspectors and both speaking French? Monsieur Derval understood that we were about to receive a visit from a gentleman of Scotland Yard. I was sent along in case there were language problems. I do not represent the theatre, you understand, but I speak English. Simenon. Georges Simenon. How do you do?’

Joe handed his card to the young man. ‘Monsieur Simenon? You are French?’ Joe asked.

‘No. Belgian.’ The man who greeted them at the stage door was reassuringly untheatrical, Joe thought. Of medium height and soberly dressed in tweeds with thick dark hair and a pale complexion, he looked like a lawyer or an accountant. Although not far into his twenties, Joe judged, he had already developed a frowning seriousness of expression. But the lines on his forehead were belied by a pair of merry brown eyes, peering, warm and interested, through heavy-framed spectacles. A strong, sweet smell of tobacco and a bulge in his right pocket told Joe he’d been passing some time at the stage door waiting. He seemed genuinely pleased to see them.

‘Everyone else is doing what they usually do an hour before the matinée. You may go wherever you please in the building – just try to keep out of the way as far as you can. I’ll come with you. You’ll be needing a torch, I think. And a guide. I know where the light switches are. Front of house is empty – the orchestra drag themselves in at the very last minute. The cast are thumping about backstage. Clattering up and down stairs and being drilled by Monsieur Derval. Soon they’ll be screaming and yelling, tearing each other’s hair and stealing each other’s lipstick! Oh, and you’re expecting to see Josephine?’ He paused for a second, and continued with a slight awkwardness. ‘Can’t promise anything as far as she’s concerned, I’m afraid. Not the most reliable . . . In fact, she’s usually late. She’s not arrived yet and may well drift in, still eating her lunch, and go straight onstage. We’ll just have to wait and see. I’ll give you a call when she gets here.’

He seemed to tune into the two policemen’s puzzlement. ‘You must be wondering what I’m doing here, answering for the star? Wonder myself sometimes! I’m not an employee of Josephine’s – more of a friend. I’m a journalist in fact. I met her last year when she arrived, fresh off the boat. I was a stage-door admirer, I’m afraid, turning up with a bunch of roses. She talked to me. I discovered she knew not a word of French.’ He smiled. ‘Her English isn’t wonderful either! She was an instant success and, as you can imagine, began to receive sacks full of mail. Every day there were invitations from some of the grandest people you can imagine, offers of hospitality of one sort or another, gifts, proposals of marriage – thousands of them. And, of course, the poor girl was unable to answer a single one of them. Couldn’t even manage a thank-you note for a diamond necklace or a De Dion-Bouton! I began to help her out. She’d tell me how she wanted to reply, I’d put it into suitable French – or English – and see that the notes were sent off.’

‘You’re her secretary?’

‘It’s not that formal. No. As I said – I’m a news reporter. And I’m a friend who writes for her. But – to business. I expect you’d like to inspect the scene of the crime first? The box? It hasn’t been used since the killing. Nor has the other one. All entry barred. The police squad didn’t spend a great deal of time up there . . .’ His voice was slightly quizzical. ‘Commissaire Fourier in attendance. The big gun! They hauled off the corpse and the weapon – and a suspect they claim to have caught red-handed – gave firm instructions to leave the site alone and that’s the last we’ve seen of them. Wondered when you’d be back . . . There must be much still to discover . . . Have they made an arrest? Have they charged their Englishman with murder? Did they have any success with the fingerprinting, do you know?’

‘Which branch of journalism are you employed in, monsieur?’ asked Joe with the air of one who knew the answer.

‘Crime,’ he replied, smiling.

‘Then you’ll never be without material in Paris,’ said Bonnefoye acidly.

‘And we’re working on the assumption that the suspect they carted off is an innocent man,’ Joe felt bound to assert.

‘I never thought otherwise,’ Simenon said graciously.

Their guide switched on the house lights and the inspection began. Joe and Bonnefoye opened up the two boxes and tick-tacked rude messages to each other over the void, agreeing that Wilberforce Jennings’ account was probably entirely accurate. The reporter went obligingly to occupy a position centre stage, confirming that he had a clear and close view of Joe in one and Bonnefoye in the other box, sight limited only by the available light. With nothing of note in Jardine’s box, the three men gathered at the murder scene and looked about them. The grey upholstery with its sinister dark stain was witness to the exact spot on which Somerton had breathed his last.

Simenon waved a hand at the walls where patches of graphite from the fingerprinting brush stippled the paintwork. ‘Dozens, you see! Not one of them bloodstained. I expect the ones they’ve taken belong to the world and his wife – and his mistress; everyone who’s been in here since it was last cleaned. And the knifeman could have been wearing gloves. Not much of a tradition with us, I understand, Inspector – fingerprinting? Chances are, if they can pick up the murderer’s prints on these surfaces, they’ll have no records to compare them with. You’ll have to catch him first and then match them up.’

Joe took the torch he was offered and trained it systematically along the walls, since it seemed to be expected of him. He wasn’t hopeful that this murderer had left a trace of himself behind. He wasn’t likely to have paused to decorate the walls with his calling cards, but he had to come and go through the door. Yes, the door, if anything, would be the most revealing, Joe thought and said as much.

‘Unless he had the forethought to leave it ajar,’ murmured Simenon. ‘And shove it open with his foot. That’s what I’d have done. He was right-handed, I assume? Is it known?’

Bonnefoye nodded. ‘And Somerton’s lady friend who nipped off early could have ensured it was left open when they entered – had to have a draught of air or some such excuse – so he could push it open with an elbow.’

‘Indeed? Mmm . . . So he’s in and out with no need to touch anything with or without bloodied hand or bloodied glove?’

‘Wouldn’t he have closed the door behind him in anticipation of his private moment? Instinctive, you’d think,’ said Joe, ‘covering your back?’

‘A man with cool nerves would chance it. With the finale going on . . . star on stage . . . no one’s going to be prowling about the corridors. And his back could have been covered by his blonde conjurer’s assistant keeping cave outside, holding his cloak ready to slip over any bloodstains he might have on him.

‘You know – I think the man probably wasn’t wearing gloves . . .’

Joe was enjoying the man’s musings. ‘Yes. Go on. What makes you say that?’ he asked.

‘Not their style. It’s a tricky manoeuvre slicing through flesh – muscle and gristle. They like to have complete control of the blade in their fingers. I’ve witnessed a demonstration.’ He shuddered. ‘They’ll tell you a gloved hand can slip. And why bother when it’s easy enough to wipe the blade afterwards? It had been wiped clean?’

‘It had,’ said Bonnefoye.

‘There you are then. No gloves.’

‘But tell me, monsieur: they? Who might they be? Do they have a name and number? An address, perhaps? Where they might be reached?’

‘The professionals. You must be aware of them, Inspector. You clear up their nasty little messes often enough.’

‘The gangs of the thirteenth arrondissement? The Sons of the Apaches, I’ve heard a romantic call them.’ Bonnefoye grinned at Joe.

‘No, no! Those buffoons are window-dressing! Practically a sideshow for the tourists. Did you know you can hire them by the hour to stage a knife-fight in the street, right there on the pavement in front of whichever café is opening that week? They even have stage names: Pépé le Moko, Alfrédo le Fort, Didi le Diable, La Bande à Bobo. Two rival gangs will fight it out with blood-curdling oaths and threats, egged on by their molls. And all to an accompaniment of delighted squeals from the clientele. Then, after a suitable interval,’ he looked slyly at Bonnefoye, ‘on they come – the hirondelles, the swallows flashing about in their shiny blue capes. The boys in blue sweep up on their bicycles and confront both gangs who, miraculously, always seem to turn around and join forces against the flics. Oh, it’s a pageant! You could put it on at the Bobino! The bad boys always know exactly the moment to disappear down the dark alleys, leaving really very little blood behind them. Just a few spots for the patron to point out to his customers. These – as you might expect – are perfectly unscathed but have worked up quite a thirst in their excitement. No, this is not their work. And no, I can’t give you any names. They have none.’

‘Is what we’re hearing your theory or your evidence, monsieur?’ asked Joe, intrigued.

‘I’ve told you what I do for a living. To report on crime you have to be close to the criminals. As close as they will allow you to approach. I know, or think I know, a good many people who are known to you also – by reputation. I’ve shared a drink with them . . . talked to them . . . drawn them out. I have friends in some pretty low places! Brothels, opium dens, absinthe bars . . . Sometimes they shoot me a line for their own benefit. But even their lies and false information can give much away if you’re not taken in by it . . . are prepared to analyse it. I’m aware of what they can do – of what they have done – but I have no name to offer you and would not offer if I knew it . . . The last man who let his tongue run away with him was found two nights ago in the canal with his mouth stitched up. They have a brutal way with those who would . . . vendre la mèche . . .?’

‘Sell the fuse?’ said Joe, puzzled. ‘Oh, I see . . . Give away the vital bit? Squeal. Inform.’

‘The warning is reinforced periodically. Whether it’s called for or not, I sometimes think,’ he added with chill speculation.

‘Is that all you have for us? Aportentous warning empty of any substance?’ Joe’s voice was mildly challenging.