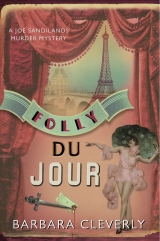

Текст книги "Folly Du Jour"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

‘When he could be looking at la belle Josephine and a hundred chorus girls wearing not so much as a bangle between them? Worth a try, I suppose. You never know your luck,’ said Joe doubtfully. ‘Can you oblige, Bonnefoye?’

‘Easy. We have access to records of every foreigner using accommodation in the city. There are about six hotels the English prefer to use. We’ll try them first.’

‘And now, George, we’ve got you in your box . . . The chairs – pulled into a companionable huddle . . . the tray of convivial drinks served and consumed. Tell us about your mystery guest. Who was she? Why are you twisting about in an effort to keep her identity from Fourier?’

Irritated by George’s dogged silence, he tried a full assault. ‘Alice Conyers paid you a visit, did she? Yes, I knew she’d survived. Though I had no idea she was in France.’

‘It’s hard to imagine, eh, Joe? You’re expecting your cousin and there bobs up at your elbow a girl you thought had died in terrible circumstances five years ago. I was never more surprised! She seemed well and happy and sent you her fond regards.’

‘She has good reason to remember me with fondness,’ said Joe bitterly. ‘But why did she show herself to you? I always thought the two of you were pretty thick but . . . all the same . . .’ Too late he heard the tetchiness amounting to jealousy in his voice. ‘A risky manoeuvre on her part, I’d have thought,’ he said more firmly. ‘You could have arrested her!’

‘I did. She escaped.’ George was breezily defiant.

Joe snorted in exasperation. ‘Sir, are you saying you had the woman in your grasp and you let her loose?’

‘That’s about it. Yes. And, Joe, that’s exactly where I want her – on the loose. At liberty, to go where she pleases.’

Into the astonished silence he set about his explanation. With rather less than his usual confidence he spoke: ‘I’ve resigned my position, you know. I’m free for the first time in my life of duty, protocol, intrigue, politicking of any kind. I’m not so old I can’t enjoy the rest of my life. Got all my faculties and bags of energy. Knees not wonderful but I hear they can do amazing things in Switzerland with knees. Funnily enough, at the very moment when you might say my life was hanging by a thread, I’ve realized the value of it. It came to me on the bank of the Seine this morning. I’m going to make good use of whatever years are left to me and I’m not starting on them by taking the life or liberty of another. Especially not a woman like Alice whom you rightly surmise I have always held in esteem and affection.’

The expression in the blue eyes he turned on Joe was, for once, not distorted by guile, amusement or cynicism. The eyes were direct and piercing and Joe found it hard to meet them. How could he accuse George of negligence in letting Alice Conyers go free when he’d done exactly the same thing himself five years before?

‘And lastly, before you fall asleep, my boy, you’ll be wanting to hear about the rascal Somerton. Do try to concentrate. You really ought to know what it was he did to make a mighty number of people want to stick a dagger in him. Including yours truly!’

Chapter Fifteen

George took a fortifying swig of his brandy and lapsed into thought.

‘Look here, chaps,’ he said finally, ‘I know you’re both men of the world and violence is your stock in trade, so to speak, but what I have to tell you is shocking and offensive. In the extreme. You must be prepared. It may be that, when you understand the kind of man he was, you’ll be less eager to pursue his killer. A plague-infested rat . . . a striking cobra . . . Somerton . . . the world would always be well rid of them.

‘He was commanding officer of a military station in the north of India. Before the war. Known to me – we’d met briefly during a tour on the Frontier and I’d formed a dislike for the fellow then. The affair I’m about to mention was hushed up to avoid bringing disgrace on the British Army at the time so – if you’ll excuse me – I’ll respect that and give you no names, no pack drill.

‘You’ll know, Joe, that when outfits turn rotten, you always find the cause of it is the commanding officer. And Somerton’s was a rotten outfit. Oh, outwardly crisp – their drill and appearance could never be faulted. Indeed, in the way of such men, he was a stickler for detail, regimentation. So, the fact that he was running a brutish, bullying crew, moulded by him in his own image, was likely to be overlooked. They were never seriously tested militarily – I’m speaking of the period before the war when there was always the danger of units turning soft through inactivity and boredom – so I can’t speak for their fighting qualities. After the event, the whole corps was broken up and dispersed. I presume they went to France and many must have perished on the battlefields, along with the rest of the army of the day. I’m probably the only man left alive who would be willing to tell the tale but there must be many more who remember and will always stay silent.

‘There was a native village on the outskirts of the station . . . usual arrangement. Many of the local men undertook work for the army. One day the rubbish collectors, going about their business, found a body on the rubbish tip. It was the corpse of a young girl from their village. They all recognized her. She was the daughter of the dhobi – the laundryman.’ Sir George was uneasy with his story, his delivery flat and deliberately uninvolving. ‘They thought at first she’d been torn apart by jackals. The station doctor was summoned. Fast turnover of doctors in that unit. They never stayed long before asking for a transfer and this one was newly arrived. He involved himself before consulting the commanding officer. Had the body brought in for examination.

‘The girl had been the victim of multiple assaults. Of a sexual nature. She’d been raped. Many times. Also beaten and cut with a dagger and, finally, strangled. She was twelve years old.’ George’s head drooped and he seemed unable to carry on.

Joe and Bonnefoye could find no words to encourage him.

‘Somerton tried to cover it all up. No need of a report for such a matter. Who was lodging a complaint? The father? Pay him off! A few rupees would close his mouth. But the medical officer was made of stern enough stuff to stand up to him. He sent in a full report to Somerton’s superior officer and he sent a copy to me.’

‘Was a proper investigation conducted?’ asked Joe.

‘I insisted on it. I put my best men in to get to the bottom of it and when I heard what they’d discovered I took steps. They found that the girl had been sent – against her will and against custom – into the camp to deliver items of laundry urgently needed by the CO. Women never ventured near the place as a rule – the men had a reputation for savagery of one sort or another. The poor child must have been terrified to be given the errand but girls in that country obey their fathers. She’d delivered it to Somerton’s quarters. She’d been seen going inside and coming out again. This was the story my men picked up from every witness. A word-perfect performance, they judged. Too perfect. Rehearsed. They went to work and after some days finally found sitting before them at interview a young chap fresh out from England and as yet untrained in the ways of that regiment. He spilled the beans.

‘Put his own life in danger, of course, by his assertions and we had to take him away directly to a place of safety and hold him in reserve for the trial. He stated that the girl had indeed come out of the CO’s quarters but thrown out screaming and bleeding and in great distress – by Somerton himself. Some of his men had gathered round on hearing the din and our recruit had been horrified to hear his instructions: “She’s all yours, lads, if you can be bothered!”

‘Our chap ran away and hid and no one was aware that he’d seen anything, but he was able to give a full list of those involved. We had the names and rolled it up from there. The men had bragged about it to each other openly afterwards. They never knew exactly who had shopped them. It wasn’t difficult to get a confession from most of them.’

‘And you left him alive, George?’ said Joe quietly.

‘A court martial was held and he was found guilty. Kicked out of the army with every ounce of parade and scorn they could muster. A pariah for the rest of his days. I thought that was punishment enough. At the time. I wish now I’d had the bugger shot. I could have arranged it.’

‘Why did you hold off?’ Bonnefoye wanted to know.

‘The fellow had a wife and young son back home. And, on the whole, a cashiering makes less of a splash than an execution.’ He sighed. ‘Discretion, always discretion.’

Suddenly angry, he burst out: ‘And now see where discretion and pity have landed me! In danger of losing my head because the silly bugger’s got his comeuppance! And I didn’t even have the satisfaction of plunging a dagger into his snake’s heart! It’s a thankless task you two fellows have got on your hands. If you find out who ordered up this assassination I shall have to ask you to congratulate him before you slip the cuffs on.’

‘He didn’t kill Somerton, did he?’ Bonnefoye commented when Sir George, finally exhausted, had excused himself and gone off to his room.

‘What makes you change your mind?’

‘At the end, when he lost his temper and spoke without restraint . . . I believed him when he said he would have plunged the dagger into the man’s heart. He would have done just that. Quick and soldierly. He’d quite forgotten for the moment that Somerton had died from a gash from ear to ear. I can’t see Sir George sawing away like a pork butcher to bleed a man to death, can you?’

‘No, I can’t. But I’ll tell you what, Bonnefoye – the wretched man’s gone off to bed leaving us with a mass of things to do tomorrow. I say, will you . . .?’

‘Yes. I’ve arranged for a deputy to take my place and bring me notes of the conference afterwards. I’ll be of far better use to international crime-fighting if I pursue this case actively. We’ll allocate tasks in the morning . . . Though I leave the Embassy to you – I think you have the entrée!’

‘And, speaking of entrées – your evening, Bonnefoye. How did you get on in the boulevard du Montparnasse?’

‘Ah, yes! Mount Parnassus, home of Apollo and the Muses! Well, there was music and verse, certainly, but it wasn’t at all classical. The address Francine Raissac gave you turned out to be a jazz café. And, you know, Joe, I’d have gone in there anyway! The music I heard as I was passing was irresistible. The performers were a mixture of black and white. There was a guitar but a guitar played very fast, a violin and a clarinet and something else I can’t remember . . . a saxophone? Odd assortment of instruments – you’d swear they only just met and put it together. But brilliant! And the crowd was loving it.’

‘Did it have a name, your café?’ asked Joe, intrigued.

‘Oh Lord! Some animal . . . they’re all called after birds or animals, have you noticed? Le Perroquet . . . Le Boeuf sur le Toit . . . L’Hirondelle . . . Le Lapin Agile . . . And here’s another one – Le Lapin Blanc – that was it. It’s a bit further out than the Dôme and not as far as the Closerie des Lilas.’

‘What sort of people were in the crowd? Did you know any of them?’

‘No one on our books, if that’s what you mean. Upright citizens, I’d say. Large number of Americans – you’d expect it in that part of Paris. Poets, painters, photographers and their models and muses all packing the place out. Sixth arrondissement bohemian, to use an old-fashioned word! But living up to it – you know, a bit self-conscious and not the real thing. Every client looking over his shoulder spotting the latest outrageous artist. And every outrageous artist looking over his shoulder spotting the mouchards from the police anti-national department. Who’s likely to be snitching on them? The local commissariat is still on the alert for extreme views of one sort or another. Marxism, Fascism, intellectualism. Dadaism. Is that a word? They especially don’t like that! We’re supposed to be on the watch for it. Not sure what we’re expected to do with it if we find it . . .’

‘Anyone spot you?’

‘No, indeed! I thought I blended in rather well. And no one was making inflammatory statements. The clientele weren’t annoying anyone when I was there. Usual mixture of thrill-seekers and thrill-providers. Well-heeled but quirky. Silk scarves rather than ties, two-tone shoes, little black dresses and cocktail hats – you’d have felt very much at home, Joe.’

‘I’d never wear a cocktail hat to a café,’ muttered Joe.

‘Unless you were going on somewhere. No . . . the seediest customers were a couple of gigolos . . . nothing too flamboyant . . . and a pair of politicians. The rest were businessmen, rich tourists and poseurs, I’d say. It’s obviously the place to be seen this month.’

‘Nothing unusual? No dope? No under-the-counter absinthe?’

‘None that I noticed and I notice more than most. The only odd thing, and it didn’t occur to me until I was on the point of leaving, was that two of the men had gone off into the back quarters, separately, and neither had come out again. I followed the second of them after a discreet interval. Cloakrooms, as you’d expect. The gentlemen’s accommodation was impressive – as good as a top hotel – and I’d assume the ladies’ was of equal comfort. Nothing untoward going on. The man I was pursuing was not in the room. He’d disappeared. Alongside the cloakrooms was a carpeted staircase.’

‘You didn’t resist?’

‘Whistling casually, I followed on up to a landing. A table with a lavish display of flowers and three closed doors. No numbers. They each had a – fanlight? – a pane of glass over the top. Well, I judge the management have some sort of mirror system in place because the middle door opened at once, before I’d even knocked, and a maître d’hôtel type appeared. Large, ugly, unwelcoming but exquisitely polite. Well trained. He sent me straight back downstairs. I was trespassing on private property, apparently.’

‘Some sort of house of ill repute, are you thinking? A house of assignation?’

‘Yes. Something in the nature of the Sphinx which is close by – just off the boulevard by the cemetery. There’s a call for it. Tourists seeking thrills and well able to pay over the odds for their indulgence. And citizens come over from the affluent Right Bank into the Latin Quarter in search of a slight frisson of danger, a whiff of spice, but not the out and out dissolution on offer round every corner in Montmartre. Another attraction is that the maisons d’illusion of this type guarantee anonymity. From a perfectly innocent meeting place, thronged with people – like the jazz club – clients present themselves, are checked and gain entrance through an antechamber. They leave through a different door. All very discreet. You could run into your brother-in-law who’s an archdeacon and you needn’t blush for your presence there. You’d be just another fan of that wonderful saxophonist.’

‘This Sphinx you mentioned . . .?’

‘. . . is generally reckoned the top of the tree. It’s reputed for the calibre of its girls. They started with fifteen and now have about fifty. Beautiful of course but also well-educated and charming – good conversationalists. Many of them – or so it’s said – have aristocratic pretensions: Russian princesses, Roumanian countesses, English nannies.’

‘Top drawer stuff!’

‘And it’s fresh and modern. Forget the red plush decadence of the Chabanais and the One-Two-Two! The Sphinx is avant-garde, art deco . . . Good Lord! It’s even air-conditioned! It’s the sort of place where responsible fathers take their sons for their first serious experience with the fair sex.’

‘And our nameless establishment over the White Rabbit jazz club may have set up as a rival?’

‘Perfectly possible. There’s an increasing demand. Every luxury liner disgorges thousands of eager sensation-seekers. Restaurants, theatre, night spots – they’ve never been so busy. And of course the brothels are going to cash in too. The Corsicans who used to run this side of life have suddenly lost authority and the market’s ripe for the taking. The North Africans are moving in but there’s a strong challenge from the lads of the thirteenth arrondissement. They’re flexing their muscles, getting Grandpa’s zarin down from the attic, and are ready for the fight.’ Bonnefoye became suddenly serious as he added: ‘But more than knives. Some of them have guns they didn’t turn in after the war ended. And the men themselves . . . they’re not untried lads. They survived the war. They’re trained killers. Killers who perhaps got used to the excitement of war and miss it?’

‘But if the guard dog was told not to admit a clean-cut and clearly solvent chap like yourself – well, that’s a bit strange, isn’t it? I’d have expected them to have dragged you in the moment you stuck your head over the parapet.’

‘Yes. I was quite miffed! I went back down into the bar and got myself a drink. Found myself next to the two I’d marked down as politicians – I vaguely recognized one and, since they were talking about government grants on animal fodder in Normandy, I think I got that right. I’d parked myself next to the two most boring men in the room! I knocked back my vermouth and was on the point of leaving when the conversation next to me started to break up. It’s always worth while listening when goodbyes are being said. People say things with their guard down that perhaps they ought not to – and more loudly.’

‘Like – “Remember me to your brother and tell him to count on my help. The Revolution’s next Tuesday, is it? I’ll be there!”’

Bonnefoye grinned. ‘In fact, my man said, “Remember me to your wife. Her soirée’s next Saturday, isn’t it? I’ll be there!” It was the bit he added that was worth hearing. At least I think it was worth hearing. You must be the judge. He leaned over and in a hearty, all-chaps-together voice said: “I’m just off to the land of wonders . . . interested? No?” And he walked out through the back door.’

‘Say it again – that last bit,’ said Joe uneasily. ‘The bit about wonders. Where did he say he was going?’

Bonnefoye repeated his words in French: ‘. . . au pays des merveilles . . .’

‘Au pays des merveilles,’ murmured Joe. He was remembering a book he’d bought for Dorcas the previous summer to help her with her French reading. It hadn’t been well received. ‘Gracious, Joe! This is for infants or for grown-ups who haven’t managed to. It’s sillier than Peter Pan. I can’t be doing with it!’ His mind was racing down a trail. He was seeing, illuminated by a beam of hot Indian sunshine, a book, fallen over sideways on a shelf in an office in Simla, the cover beginning to curl, a peacock’s feather marking the place. The same edition. Alice au pays des merveilles. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Alice.

Surely not. He knew what Dorcas’s judgement would have been if he’d confided his mad notion: ‘Sandilands in Fairyland.’

The idea would not go away. Alice Conyers, fleeing India, Gladstone bag stuffed with ill-gotten gains of one sort or another, stopping over in Paris – might she have used her formidable resources to set herself up in a business of which she had first-hand knowledge? She might well. Bonnefoye waited in silence, sensing that Joe was struggling to rein in and order his thoughts.

‘Tell you a story, Bonnefoye! At least Part One of a story. I think you may be about to make a bumbling entrance with me into Part Two. As the Knave of Hearts and the Executioner, perhaps?’

Bonnefoye was intrigued but scornful. ‘That’s all very fascinating but it’s as substantial as a spider’s web, Joe!’

‘But we’ll only find out the strength by putting some weight on it, I suppose. Your face is known there now. My turn to shoot down the rabbit hole. It’s my ugly mug that they’ll see leering in their mirrors next time! And, if madame’s there, I think I know just the formula to persuade her to let me in. There’s something I shall need . . . Two items. Didn’t I see a ladies’ hat shop down there in the Mouffe? Two doors north of the boulangerie? Good. What time do they open, do you suppose?’