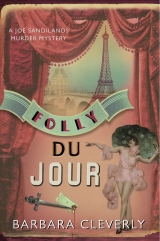

Текст книги "Folly Du Jour"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Chapter Nine

Joe decided to tell the driver to drop him in the place du Tertre in the heart of Montmartre. The cab moved off easily northwards, threading its way according to Joe’s directions, along the Right Bank, taking a westerly route through Paris’s most spectacular streets and on up the rue d’Amsterdam. They turned on to the boulevard de Clichy which wound like a necklace along the wrinkled throat of the ancient village on the hill.

As they crossed the place de Clichy, he glanced at the billboards of the Gaumont Palace cinema with its imposing Beaux Arts façade. Le plus grand cinéma du monde, it announced. Today they were offering a matinée pro-gramme, a repeat showing of a pre-war thriller: Fantômas III. Le mort qui tue.

Fantômas, Part Three. The Murderous Corpse. One of a series of horror stories that had swept France. Joe was not a fan. He’d stopped reading them after the second book when he’d worked out that the Emperor of Evil whose sadistic exploits were recounted always escaped the law. At the end of every story one implausible bound set him free from the clutches of the tenacious policeman who’d vowed to bring him to justice. Joe lost patience with the good Inspector Juve. But he was a human like Joe, overworked, mortal and fallible and fighting a hydra-headed, super-human essence of wickedness. A completely implausible villain, for Joe. He much preferred Professor Moriarty. Though he had shown a tendency to survive unsurvivable plunges into waterfalls.

They attacked the hill by way of the rue Lepic, lined with market stalls. Progress up the cobbled streets was slow. They were impeded every few yards by two-man push-and-pull handcarts whose pushers and pullers stared in disdain at any motor vehicle attempting the steep incline, taking their time, demonstrating defiance. The worst blockage was caused by a two-wheeled cart being pulled along by an ambling old horse. His sole interest was in the contents of the nosebag he wore and he eventually ground to a halt outside a grocer’s shop. La Bordelaise looked prosperous, its windows bright with bottles of wine and oil, baskets of olives and dangling saucissons. Sticking his head out to assess the delay, Joe was caught by the scent of roasting coffee beans. On impulse he called to the driver to wait and dashed into the shop. A moment later he climbed back into the taxi with a fragrant bag of beans in his hand.

He paid off his taxi in the place du Tertre and looked about him, getting his bearings. He strolled off along the north side of the square, getting a feeling for his surroundings. More strident than it had been in its heyday half a century ago when Pissaro, Cézanne and Renoir had sat at their easels on exactly this spot, painting the crossroads scene. More self-consciously colourful, tricked out, alluring, completely aware that it had something valuable to sell. Itself. Montmartre was a tart. But people fell for her charms every time. And he was gladly allowing himself to be seduced.

The gaudy square was surrounded by poor streets. He turned left into one of them. Here, the children playing in the street were ragamuffins like the ones in the East End of London. Barefoot some of them, all scrawny but cheeky enough to shout rude comments at a stranger. He brushed aside offers to shine his shoes, take him to a jazz bar and other more dubious propositions. He skirted around ball games and dodged urchins swinging out across the pavements on ropes suspended from gas lamps – a dangerous game of bar skittles in which the passer-by risked losing his hat or, at the least, his dignity. Joe, in a moment of playfulness, could have wished he was wearing a top hat for them to aim for and quickly took himself in hand. Such a spurt of frivolity was not appropriate. He blamed it on the freshness of the air up here on the hilltop, the blossom, the new leaves, the wad of bills in his pocket and a feeling that all was possible. He gave the lads his police stare, put on a show of knowing exactly where he was going and they left him alone.

Every narrow street he looked down called to mind a scene already captured in paint or waiting to be captured. He turned a corner into the rue St-Vincent and found himself following a few paces behind a figure from the last century. In baggy black suit and wide-brimmed gypsy hat, guitar slung across his back, a chansonnier strolled on his way to perform perhaps at the Lapin Agile. Conscious that he was wasting time, Joe tracked him until he disappeared into the dilapidated little cottage, his entrance marked by raucous cries of welcome and a burst of song. For a moment Joe paused, tempted to go into the smoky depths. He remembered that in an earlier age it had been known as the Cabaret des Assassins.

Who would he see in there if he slid inside and took a table? He narrowed his eyes and pictured the scene. Letting his fancy off the leash, he saw: Picasso . . . Apollinaire . . . Utrillo . . . Jean Cocteau . . . and he grinned. He probably wouldn’t understand a word of the conversation! Avant-garde, fast-living, arty . . . But he knew who would understand and almost turned to share his thoughts with young Dorcas. He felt a stab of regret that his adopted niece who’d trailed through France with him last summer was not by his side. She’d have felt at home here. She’d have greeted the gypsy guitarist and talked to him in his own language. Her raffish father, Orlando, must have spent hours drinking and yarning with his fellow painters in this picturesque hovel, judging by the quantities of canvases it had inspired. And his daughter was probably on first-name terms with half the clientele!

He looked at his watch. Better left for another day. Yes, he’d come back some other time. With Dorcas. Why not? He reminded himself to find a suitable postcard to send to her in Surrey. But a different girl was higher on his agenda today.

He had work to do. A self-imposed task but tricky and not one to be attempted light-heartedly. Not heavy-handedly either though. He looked around and caught sight of a flower seller’s stall on a corner of the square. Five minutes later, armed with half a dozen of the best red roses the seller could provide, done up in a silver ribbon, he locked on to his target.

Everyone who could be outside on that May afternoon was out on the pavement. The concierges of the lodging houses had settled in chattering groups, shelling peas, their chairs obstructing the pavements. From open doors behind them drifted the fragrant smell of dishes cooking slowly in some back room. Mothers fed babies or crooned them to sleep.

Around a corner to the north of the square he came upon the faded blue sign he was looking for: rue St Rustique. The oldest street in the village and quite probably the narrowest. The three– and four-storey houses had known better days. Shabby grey façades retained interesting architectural features: elegantly moulded architraves graced doorways, Second Empire wrought-iron grilles added dignity to windows whose shutters stood wide open on to the street. Bourgeois net curtains gave seclusion and an air of mystery to the interiors.

Joe located number 78. The patch of pavement in front of the house and the cobbled road as far as the central gutter were freshly cleaned. Abroom was propped against the wall to the right of the open door, two large pots of daisies stood to attention and an eye-watering waft of eau de javel leapt from the interior and repelled him. Joe read the sign painted in art nouveau letters above the door’s architrave: Concierge.

He froze. There she was, filling the doorway, barring his entrance. Redoubtable. Cerberus? The Cyclops? He reckoned he had about as much chance of getting past her and into the building as he would have had facing up to one of those monstrous guardians. She stood, four-square, bulldog face peering at him over gold half-moon spectacles. She was holding a pile of letters to the light and shuffling through them. Sorting out the residents’ afternoon post, he guessed, and she was not counting on being disturbed. She was dressed like a badly done-up parcel; her clothes were all in shades of brown, shapeless and hanging in layers to her mid-calf. Here the tale of sartorial disaster was taken up by a pair of drooping socks and bulging slippers.

Joe did not often find himself at a loss for words and was angry with himself for hesitating to address her. He regretted now the bunch of roses in his hand. What a twerp he must look.

‘Yes? Who are you?’ Her voice would not have disgraced a sergeant major.

The challenge provoked a military response. He stood at ease in front of her with what he hoped was an air of languid confidence and managed a tight smile. ‘An English gentleman to see Mademoiselle Raissac. I understand she lives here.’ He began to reach into his pocket for his warrant card.

She stopped him with a gesture. ‘She’s not seeing callers today. She’s not well. Come back tomorrow.’ The concierge turned and, as an afterthought, seized her broom as though she thought he might run off with it. She made to go back inside.

‘Police! Wait!’

That claimed her attention. She came towards him. ‘Shh! Keep your voice down! This is a respectable street,’ she hissed at him. ‘Police? Again? She’s given a statement. Can’t you leave her alone?’

‘I will see her here, discreetly, in her own room, for half an hour or I will haul her off to the Quai des Orfèvres for a rather lengthier interview. I’m quite certain neither you nor the young lady would relish the appearance of a panier à salade outside your front door, madame.’ Joe was not at all certain that one of these sinister motorized cells would be deployed at his request for the conveyance of one suspect but the old dragon appeared impressed by the threat.

‘You’d better come in then . . . sir. And you can show me your proof of identity.’ Her voice would never be capable of expressing deference but at least it was now verging on the polite. ‘You can wait in my parlour while I go up and see if she’s prepared to see you. Through here.’

She took him to her two-roomed loge on the ground floor off the hallway and offered him a hard-backed chair. The small room which served as both kitchen and living room was sparsely furnished but neat and well polished. A few ornaments twinkled on the mantelpiece above an open fire on which a blackened pot had been left to simmer. Monsieur’s supper no doubt.

She wiped her hands on her pinny and reached for the warrant card he held out to her. Every aspect of it came under her searching eye and finally: ‘Well, it’s good that the flics are taking a serious interest in this tragedy. Bit unusual, isn’t it? Not something we’re used to round here – courtesy visits from the Law with roses in its hand. Have a glass of water while you’re waiting, young man. You look overheated,’ she said, surprising him, and poured a glass from the tap. ‘Don’t pull that face! No need to be fussy! Paris water is good water.’

Joe drank gratefully, puzzled but relieved by her change of attitude. On a whim, he reached into his pocket and took out the bag of coffee beans. ‘For you, madame. I hope you can drink coffee?’

The tight lips twitched slightly and she took the bag from him, squinting at the label. ‘From La Bordelaise! I can certainly drink that! Thank you very much.’ She set it down on a dresser beside the polished copper funnel of a coffee-grinder and went to summon her lodger. In the doorway, she turned and spoke to him over her shoulder in her clipped, machine-gun phrases. ‘Francine is a good girl. Never been in trouble with the law. She works every hour God sends. As good as a daughter to me. And she’s still reeling from the shock. You’re to treat her with respect.’

Joe’s saluting arm twitched in automatic response to the tone.

As her slippered feet thudded up the staircase, he eyed the coffee. A sop to Cerberus? It still seemed to work.

A sleepy face peered round the door at him, focused blearily on his card and, after a delay calculatedly long enough to register her protest, she opened the door with a grudging: ‘You’d better come in, I suppose.’

Her room was untidy and, Joe thought at first glimpse, perfectly charming though he would not have relished the task of carrying out a detailed search of the premises. The afternoon sun streamed in through the window illuminating, on the opposite wall, an open armoire densely packed with dresses of all colours and fabrics. They spilled out to hang in bunches on hangers along the picture rail. A treadle sewing machine with a piece of work still clamped across the needle plate stood under the window to catch the light. Against one wall of the single-roomed apartment was a bed, made up and covered with a gold brocade eiderdown. A low table held a row of unwashed coffee cups and one or two baker’s shop wrappers covered in crumbs and patched with grease.

Once he was inside, she rounded on him. ‘Two interviews in as many hours? What’s going on? I’m a witness not a suspect! Couldn’t you leave me alone to get over it? And why are they sending me the handsome inspectors? Is this a new tactic? Are there any more of you lurking round the corner? I’m not in the chorus line, you know! Though you seem to think so – are those for me?’ She seized the roses and went to put them in a jam jar that she filled with water from the wash basin in a corner of the room. ‘Doesn’t it cross your mind that you might be ruining my good name? Arriving here with flowers? Wish I’d got dressed . . .’

Francine Raissac was wearing a creased white silk dressing gown embroidered – and rather richly embroidered – with black and red dragons. Her eyes were puffy and last night’s mascara smudgily outlined her dark eyes, giving her the comical air of a cross panda. Joe said as much and she looked at him first in astonishment, then with a flash of amusement. He rushed on while he had this slight advantage. ‘Handsome inspectors, did you say? I thought I was the only stunner they could field . . .?’

‘The previous one was better,’ she said, looking closely at him, giving the question her serious attention. Her response told him the light approach was probably the effective one. ‘You’re very nearly handsome. But you’re older and you don’t have a Ronald Coleman moustache.’

‘Ah! I think I recognize my colleague, Inspector Bonnefoye?’ said Joe, trying to keep a tetchy note out of his voice.

‘Jean-Philippe.’ She managed a tease and a confirmation in one word. ‘You mean you didn’t know he was coming here?’ she asked. ‘Doesn’t the right hand know what the left’s getting up to at the Sûreté? Or aren’t you speaking the same language?’

‘We have different roles,’ Joe said, recovering from his surprise. ‘My questions will not be the same as his. He has other fish to fry.’

‘Ah, yes, of course. I understand that.’

‘I am, as you’ve noticed, English. I’m representing the interests of the gentleman who was taken in as a suspect.’

‘Not the interests of the murdered Englishman, then?’ she asked sharply.

‘His interests also,’ Joe hurried to add. ‘Indeed, I am shortly to meet his widow and conduct her to an identification of the body. An inconvenience to the French authorities and an embarrassment to us that what may prove to be a quarrel between two of my countrymen should be played out on French soil. I am doing what I can to assist the Police Judiciaire and working under the auspices of the British Embassy, of course. Interpol also, of which –’

‘All right . . . all right! You’re a big shot! Got it! Will Your Eminence deign to take a seat?’ She heaved an armful of fabrics off a sofa and Joe lowered himself on to it. ‘Oh . . . carry on then! I’m listening. I suppose I should be grateful they’ve not sent old sourpuss . . . the Chief Inspector . . . um . . .’

‘Fourier?’

‘That’s the one!’ She rolled her eyes. ‘He interviewed me at the theatre. Looks and talks as though he’s sucking an acid drop.’

‘You take, I detect,’ he said with a grin, pulling a straight pin from under him, ‘more than an amateur interest in couture?’

‘I’m sure you’re not here to count my dresses and check their provenance.’ She sounded slightly on her guard. ‘I’ll tell you straight, Mr Detective, that every last frock you can see has been acquired legally. Working in a theatre, they’re easy to pick up, if you know the right people. Did you know there’s a whole workshop underneath in the basement, sewing away day and night? I go down there sometimes and chat to the girls. They’re always pleased enough to hear news from the world above! The show clothes aren’t much use to me, of course – all ostrich feathers, tulle and lamé – but the girls pass on the occasional remnant that I can use.

‘The stars are my best source. Now – Josephine! She’s incredibly generous and if you know just when to show your face – as I do – she’ll shower you with stuff she doesn’t want or gowns she’s only worn once. We’re much the same size and sometimes she asks me to model a gown for her to help her make up her mind.’

So that accounted for the head-hugging hairdo with the over-sized curl slicked on to her forehead. Francine had a dark complexion for a Frenchwoman, Josephine had a light skin for a black American. The two girls met somewhere in the middle. But the conscious attempt to mirror the looks of the star was more than just flattery. Josephine must have found it useful to see herself from a distance in this bright young woman. And the thought came to him: ‘Probably enjoys her company, too.’

‘You get on well with the star?’

‘Yes, I like her. We French do like and admire her. It’s the Americans – her own countrymen – and the English who give her a rough time. Her dancing is too scandalous for some and she’s black. There are those – and some are influential people – who’d like to see her closed down and put on the next liner home. Not the French. We don’t care at all about her colour. And her morals . . .’ Francine shrugged. ‘Well, that’s up to her, isn’t it? She’s entertaining and stylish and we love her for it.’

‘I expect she suffers professional jealousy – one so successful at such a young age? What’s the name of the Queen of Paris Music Hall? She must be feeling a bit miffed!’

‘Mistinguett? Yes, she’s a rival but she’s big-hearted, you know. Reaching the end of her career . . . she must be in her fifties, though she still has the best legs in Paris. She can afford to rise above it. But there are two younger stars, French, both, at the Casino de Paris and the Moulin Rouge, who hate Josephine’s guts. She’s rather stolen their thunder. Either one might have hoped to inherit Mistinguett’s ostrich feather crown as meneuse de revue. And one of them has a very wealthy protector. A banker. You’d know his name. He sends his Rolls Royce to the stage door for his little mouse every night.’

‘Does Josephine mind? All this antipathy?’

‘Too busy enjoying herself. I’d say she doesn’t give a damn! In fact,’ she added dubiously, a sly, slanting question in her eyes, ‘those close to her think she doesn’t care enough. For public opinion or her own safety.’

Joe seized on the word: ‘Safety?’ he murmured.

‘Everyone thought when she had her accident last year –’

‘Accident?’

‘Not actually. It could have been nasty . . . In one of her acts, she’s lowered in a flowery globe down over the orchestra pit. A breathtaking bit of theatre! Luckily she’d decided to rehearse in the damn contraption before the actual performance.’ Francine shuddered. ‘She was on her way down from the roof in this thing when one of the cables jammed. That’s what they said. A mechanic was sacked afterwards and everyone heaved a sigh of relief. The globe suddenly tilted over and swung wide open. She ought to have been thrown out into the pit. But she’s a strong girl with fast reactions. She jumped for one of the metal struts and hung on like a trapeze artist until someone could get up into the roof and haul her up again.’

‘Good Lord! What would have happened if she’d fallen?’

‘She’d have been dead. Or so badly injured she’d never have walked again.’

‘Dangerous place, the theatre.’

And a breeding ground for all kinds of overheated nonsense, he reckoned. Scandal, exaggeration, petty jealousies. He was allowing his own tolerance of gossip to put him off track and guided Francine Raissac back on to the subject he wanted to pursue. ‘These clothes the generous Miss Baker gives you – where do they come from?’

‘Gifts. They arrive at the theatre in boxes for her to try. If she doesn’t like something, she’ll tell me to take it away. I found her knee deep in Paul Poiret samples the other day. Wonderful things! She’d just had an almighty quarrel with him and was throwing the whole lot away. Before she’d even tried them on!’ The girl was filling the space between them with irrelevant chatter, taking her time to get his measure, he guessed. And, unconsciously, going in exactly the direction he’d planned to lead her.

‘Does she have a preferred designer?’

‘Hard to say. I doubt if she can tell one style from another. She hates turning up for fittings so they take a chance on what she’ll like and send her lots of their designs, hoping she’ll be seen about town wearing them . . . I think Madame Vionnet suits her best and Schiaparelli . . . her bias cut is very flattering . . . Lanvin . . . of course . . .’

‘And your outlet for these dazzling couture items?’ he asked. ‘I’m assuming you don’t acquire them simply to decorate your room.’

‘I send them on to my mother. She has a little business in Lyon. We started it together when my father died. Location de costumes – but not your usual rag and bone enterprise. We’re building up a well-heeled client list – plenty of money about down there. Industry’s booming and it’s a very long way from Paris. Everyone wants a Paris model for her soirée!’ She indicated her sewing machine. ‘I can undertake adjustments here at source if I have a client’s measurements. Then the lady’s box is delivered and she tells her friends it’s straight from Paris – just a little confection she’s had specially run up for the Mayor’s Ball or whatever the event . . . And the label – should her friend happen to catch a glimpse of it – has a good deal to say about the success of her husband’s enterprise. And her taste, of course. We rent out things by the day, the week. A surprising number we sell.’

‘I’m talking to someone with a keen eye for fashion then? Someone acquainted with the work of the top designers of Paris?’ he said, raising an admiring eyebrow.

‘I’m sure you didn’t come here to talk fashion,’ she said doubtfully, ‘but – yes – you could say that. I could have been a mannequin if I’d been three inches taller. If I’d been five inches taller I could have been a dancer. But I’m not really interested in “could have been”. I’m a going-to-be,’ she said with emphasis. ‘Successful. Rich. I haven’t found my niche quite yet. But I will.’ And, angrily: ‘It won’t, of course, be in the professions or politics or any of the areas men reserve for themselves. We can’t vote . . . we can’t even buy contraceptives,’ she added, deliberately to embarrass him.

‘But some girls have the knack of attracting money and don’t hesitate to flaunt it . . . Does it annoy you – in the course of your work – to be seen in rusty black uniform dresses when the clientele are peacocking about in haute couture?’

‘No. Why would it? The black makes me faceless, invisible. The work is badly paid – no more than a starvation wage – but the tips are good. Men are so used to being greeted by old harridans with scarlet claws whining for their petit bénéfice, they are rather more generous to me than they ought to be. Sometimes, I flirt with the older ones,’ she said with a challenge in her look. ‘And, before you ask – no, I don’t take it any further. But they toy with the illusion that it might develop into an extra item on the programme and tip accordingly. No man wants to be perceived as a tight-wad.’

‘A five franc tip?’ he reminded her.

The eyes rolled again. ‘I pitied that girl!’

‘Ah yes. Now tell me . . . the dress she was wearing . . .’

She put her hand over her mouth and stared at him over it. ‘Ah! So you really did come here to talk fashion! Well, I talked myself into that, didn’t I?’

‘You did rather,’ he agreed. ‘So, come on! Expert that you are – I think we’ve established that much – tell me all. You divulged almost nothing to the Chief Inspector. What was it now . . .? Under twenty-five and fair? Oh, yes? Bit sketchy, I thought. Huh! Your poor old ten franc tip with his rheumy old eyes gave a fuller description of the disappearing blonde from thirty yards away! A seam by seam account of her gown! And he wouldn’t know his Poiret from his Poincaré . . . I want to know everything about her appearance and – perhaps more importantly – why you chose to pull the wool over Inspector Acid Drop’s eyes.’

She went to sit at the bottom of her bed, demurely adjusting the belt of her Chinese gown, tucking up her bare feet under her. Joe swallowed. ‘Man Ray, where are you? You should be here with your camera, fixing this moment,’ he was thinking, seized and dazzled by the theatricality of the scene. This girl with her high cheekbones, sleek black hair, snub nose and huge, intelligent eyes made Kiki of Montparnasse look ordinary. He reined in his thoughts. She was also deliberately distracting him, making time to weigh his question, possibly to plan a deceitful answer. After a further diverting shrug of the shoulder, she began her account.

‘Well, for a start, it was expensive – eight hundred francs at least, probably more. That shot silk fabric – there’s not a great deal of it about yet and the designer who’s been using it this season is Lanvin. Her shoes were Chanel T-straps. Blue satin. Her opera cloak was silk. Midnight blue. She shopped about a bit, this girl, but it was all well put together. She was carrying it under her arm – the cloak. When she came up the stairs. Her escort hung it up at the back of the booth. They often do that. Sometimes it’s to avoid tipping at the vestiaire but with the box clientele it’s usually to avoid the queue to pick it up at the end.’ She gave a twisted smile. ‘The gentlemen don’t like to be kept waiting at this stage of their evening. Now I did manage to catch a glimpse of the label on her cape. It was a Cresson. Rue de la Paix.’

‘Are you able to give me a description of this garment – an idea of the fabric?’ he asked unemphatically, pencil poised.

She thought for a moment, and deciding apparently that the information was routine and could not harm her in any way, chose to co-operate. He noted the details. In a show of helpfulness which told him he was almost certainly heading down a cul-de-sac, she even got up and walked to a basket overflowing with fabric remnants. Stirring them about, she finally produced, with an exclamation of triumph, a piece of heavy silk. Dark blue silk.

‘Not this exact fabric but – very nearly. Her cloak was made of some stuff like this.’

He thanked her and put it away in his pocket.

‘And – Cresson . . . Lanvin . . . Chanel . . . you say. These are all impressive names you mention, I think?’

‘The very best.’

‘With a distinguished client list?’

‘Of course.’

‘And if I were to traipse along the rue de la Paix to the boutiques of those you’ve mentioned and apply a little pressure or charm or cunning I might find the same name coming up?’

‘If you choose to waste your time like that . . . I wouldn’t bother. Some of these houses are hysterical about piracy. And they’re always wary of having their clients snatched by a rival. The vendeuses are well trained and they have a nose for wealth.’ She looked at him critically then smiled. ‘You’re an impressive man but you don’t look like the kind who’d spend a fortune indulging his girl!’

Joe regretted his meagre half-dozen roses.

‘Far too clever. I think you’d have considerable trouble extracting the information.’

‘So – you’re going to point out a short-cut?’

‘Why should I? The girl had nothing to do with the murder. And this answers your second question. It wasn’t her I found covered in blood. She was working for a living. If she’d been willing to give evidence she’d have hung about, wouldn’t she? But she had the sense to leg it. I’m not going to make her life difficult for her by involving her with the flics. They’re shits! And they have a hard way with filles de joie. There but for the grace of God and all that . . . If things don’t go so well for me – well, that might be the next step. Who knows? Cosying up to old farts like the five franc tip isn’t my idea of a career but I’m not stupid. I see lots of girls making a lot of money that way. I’ve had my propositions! And I see it sometimes as an easy option. A good deal of unpleasantness for a short time but the rewards are good.’

‘Francine, don’t think of it!’ Too late to snatch back the instinctive exclamation.

While he looked at his feet in confusion and she smiled in – was it triumph or understanding? – the attention of both was caught by plodding footsteps on the stairs. The concierge’s peremptory voice called out: ‘La porte!’ and Francine went to open it. Joe got to his feet, fearing that his interview was about to be cut short, ready to repel the intrusion, but instead he hurried forward to take the tray she was carrying from the old woman’s hands. He carefully balanced the weight of the silver coffee pot, two china mugs, a jug of milk and a plate of Breton biscuits, adding his own thanks to those of Francine: ‘Oh, Tante Geneviève, you shouldn’t have!’

The dragon looked around and, apparently happy with what she saw or didn’t see, cleared the top of the table to make way for the tray, gathering up the dirty cups and wrappers, grunted, and went out.

‘I don’t have much experience of concierges,’ said Joe, ‘but I’d have thought room service of this kind is a bit out of the ordinary? Did I hear you claim that lady as a relative?’

‘I call her “Aunty” and I’ve known her forever, but she’s my godmother. Her husband was wounded in the war. Has never worked since. They scrape a living. My mother would only agree to my continuing to live alone in the wicked city if I was under someone’s wing.’ She smiled and added thoughtfully: ‘And she was quite right. It’s not always convenient to have a mother hen clucking after you, but the advantages are considerable. My rent is fair, not extortionate as it can be for most young girls trying to live by themselves. No spirit stoves allowed in the rooms, of course.’ She looked around at the quantities of fabrics festooning the room. ‘And this would be a fire hazard if I attempted to use one. So – occasionally, she brings me coffee. Inspector Bonnefoye rated one too.’ Francine sniffed the coffee as she poured it out. ‘But not as good as this! Mmm! Moka? And no chicory!’ She looked at him with fresh speculation. ‘The old thing’s brought out her best for the English policeman. Now what on earth did you do to provoke this attention?’