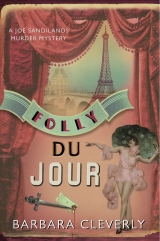

Текст книги "Folly Du Jour"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

His conflict was cut short by an arresting fanfare of notes on a trumpet followed at once by a blaring blue jazz riff from the orchestra pit. He was aware of a simultaneous dimming of the electric house lights. The blonde girl across the way opened her mouth in anticipation and wriggled forward in her seat with the eagerness of a six-year-old at a pantomime. George sighed and came to a decision. In the seconds before the light faded, he did what he could. Oblivious of the hush descending on the crowd, he rose to his feet and slipped on his white gloves. He sought out and held the eye of his opposite number.

Imperious, imperial and impressive, over the width of the auditorium, Sir George Jardine delivered a command.

Chapter Two

Abandon target! Withdraw at once!

The soldier’s silent hand language flashed, eerily blue in the dimming house lights, across to the opposite box. Unmistakable to a man who had been a fellow officer. On the Frontier, grappling often in hand-to-hand combat with lethally savage tribesmen, officers had learned from their enemy that in close proximity you communicated in silence as they did or you got your head shot off. Would Somerton remember and respond? Or would the man summon up what vestiges of self-respect he still had, to affect ignorance or rejection of the old code? George calculated that he could not depend on touching any finer feeling, on awakening any sense of regimental pride across the void. No – ugly threat was the only weapon left in his armoury. To emphasize his point, he added a universally recognized gesture. He drew the forefinger of his left hand slowly across his throat. Do as I say or else . . .

At that, Somerton threw back his head and laughed. Shaking with amusement and hardly able to keep his hands steady, in the moment before the last light went out, he returned the signal: Message received and understood.

Bloody French audiences! George remembered they always took their time settling. But the musicians seemed to be well aware of this and mastering the situation. The trumpet solo had silenced most and there now followed, as the last mutterings faded, the last shuffling subsided, a clarinet performance which stunned George with its fluency. Not his style of music at all. Jazz. But he could see the point of it and had been made to listen to the quantities of recordings that had filtered through to Simla and Delhi along with the ubiquitous gramophone. It was one of his party tricks to discuss in an avuncular way the latest crazes with his young entourage. And this was an experience he would want to share with them on his return. What he was hearing, all his musical senses were telling him, was exceptional. He rummaged in his pocket and took out his cigar-lighter. A discreet flick of the flame over his programme gave him the name: Sidney Bechet. English? French? Could be either. Even American perhaps? He’d file the name away. The chap was an artist. Could take his place in the wind section of the Royal Philharmonic any day. Given the right material to play.

He was so absorbed by the music, leaning forward over the edge in an attempt to get a clearer view of the almost invisible soloist, he didn’t hear her enter. The presence of a stranger in his box was betrayed by a rush of remembered scent carried towards him on a sudden air current as the door opened quietly and closed again. The effect on George was instant. Memories had ambushed him before he could even turn his head.

The scent of an Indian garden at twilight . . . L’Heure Bleue he’d been informed when he’d dispatched some gauche young subaltern to make discreet enquiries. The aide had returned oozing information, parroting on about vanilla, iris and spices. George had been gratified and amused that the young man had been received with such voluble courtesy by the wearer. Amused but not surprised; she had always been able to charm . . . enslave wouldn’t be too strong a word . . . his impressionable young men.

The name said it all. The Twilight Hour. He didn’t need to listen to accounts of top-notes and bases. It spoke, for him, in a voice soft as velvet, of the swift, magical dark blue moment between sunset and starlight. But, intriguingly, it brought with it an undertow of something sinister . . . bitter almonds . . . the scent of death. George shivered. The scent of a woman long dead. A woman he had mourned for five years. Silently in his heart, never in his speech.

And here, in this gaudy box, in frenetic Paris, the scent seemed as out of place as he was himself. He whirled angrily to confront whoever had invaded his privacy and – idiotically – with a thought to challenge the invader for daring to wear a perfume which for him would forever be the essence of one woman: Alice.

‘Alice?’

George’s voice was an indistinct croak expressing his disbelief, his raised hand not a greeting but an exorcism, an instinctive gesture of self-protection, as he peered through the gloom, focusing on the dark-clad figure standing by the door. An elegant gloved hand released the hood of the opera cloak allowing it to slide down on to her shoulders. He could just make out, with the aid of the remaining dim light from the orchestra pit, the sleek shape of a blonde head but the face was indistinguishable. Her finger went to her lips and he heard a whispered: ‘Chut!

’ In a second, the woman had slid into the chair at his side and had grasped his hand in greeting. She leaned and whispered into his ear: ‘George! How wonderful to see you again! And how touching to find you still recognize me – and in the dark too! Alice? Am I then still Alice for you?’

‘Always were. Always will be. Alice,’ he mumbled, struggling for a measure of control. He hunted for and caught her hands in his, pressing them together, moving his grasp to encircle both her slim wrists in one of his great hands, his gnarled fingers closing in an iron and inescapable grip.

‘And, Alice Conyers, you’re under arrest.’

Chapter Three

She laughed and winced but made no attempt to struggle. ‘Let’s enjoy the performance first, shall we? And . . . who knows? . . . perhaps I’ll surrender to you later, George?’

Her purring voice had always, for him, spoken with a teasing double entendre in every sentence. He had dismissed it as a delusion, the product of his own susceptibility, a fantasy sprung from overheated and hopeless senile lust. No one else had ever remarked on it. But the voice he was hearing again, the style, the breathed assumed intimacy – all this was telling him that it was indeed Alice he held in his grasp.

‘I do hope you’re prepared, George? This can be rather stimulating! The show, I mean! Elderly gents carted off, blue in the face and frothing at the mouth, every evening, I hear. Got your pills to hand, have you? Last will and testament in order? Perhaps you should tell me whom to ring just in case . . .’ She broke off at the first twitch of the pearl-grey curtains. The lightly insolent tone was unmistakable and he remembered how he’d missed it. George swallowed painfully, unable to reply.

With a thousand questions to ask the woman at his side, a thousand things to tell her, he was reduced to silence by the swish of the curtains as they swung back revealing a brilliantly lit scene. George stared at the kaleidoscope of vivid colours filling the stage, a controlled explosion of fabrics and patterns. The set conjured up the interior of a sumptuous Parisian department store – or was it meant to be a boutique on the rue de la Paix? Silks, velvets, chiffons and furs hung draped about the stage, arranged with an artist’s eye for effect. After the minutes of darkness, the assault on the sense of sight was calculatedly overwhelming. Another surprise followed swiftly. Set here and there against the background colours, a number of dressmakers’ dummies – mannequins, they called them over here – gleamed pale, their pure, sculpted nakedness accentuated by the profusion of clothes behind them. At a teasing spiral of sound from the orchestra the figures came to life and began to parade about the stage.

They were actually moving about! Dancing! George could hardly believe his eyes. He released Alice’s wrists at once and cleared his throat in embarrassment. A scene of this nature could never have been staged in London. He tensed, wondering whether he should at once set an example and make noisily for the exit, tearing up his pro-gramme and tossing it into the audience like confetti in the time-honoured tradition, snorting his disapproval. Writing off the remainder of what promised to be a disastrous evening. Apparently catching and understanding his sudden uncertainty, his companion put a hand on his arm, gently restraining.

George watched on. Was it his imagination . . . or . . .? No. He had it right. The girls, without exception, were tall and lovely and – yes – one would expect that of chorus girls. Rumour had it that they were all shipped in from England. But this bunch were all blonde or titian-haired with alabaster-white skin. After the years of exposure to Indian-brown limbs, this degree of paleness struck him as exaggeratedly lewd. While he was pondering the reasons for this blatant piece of artistic stage management, the girls started on their routine.

To his bemusement the chorus-girl-mannequins were beginning to act out a scene of shopping. They were selecting garments held out for their inspection by a group of vendeuses whose sketchy notion of uniform appeared to be a pair of black satin gloves and a black bow tie. Their clients inspected the garments on offer and saucily began to put them on, layer by layer, tantalizingly and wittily not always in the expected order. It was a while before George realized what was going on and when he did he began to shake with suppressed guffaws.

Alice leaned close and whispered: ‘A striptease in reverse. They start naked and end up in fur coats. Different, you’d have to admit! You’re to think of this as an aperitif,’ she murmured.

The girls, fully clothed at last, eventually took a bow to laughter and applause and swayed off, flirtily trailing feather boas, silk trains and mink stoles, leaving the stage empty.

The lights went out at once and a backdrop descended. A single spotlight was switched on, illuminating in a narrow cone of blue light marbled with tobacco smoke, an area of stage front right. It picked out what appeared to be the contorted limbs and trunk of a tree. The drums took up a strong rhythm and a tenor saxophone began to weave in and out, offering a flirtatious challenge to the beat, tearing free to soar urgently upwards.

The shape on stage began to move.

George could have sworn that a boa constrictor was beginning to ripple its way down the trunk then he gasped as the tree straightened. A second light came on from a different angle, compelling his eye to refocus. He now saw a massive black male figure carrying on his back, not a boa, but a slim, lithe and shining black girl. George forgave himself for his failure to make sense out of the contorted figures: the girl was being carried upside-down and doing the splits. Her limbs were distinguishable from the man’s by their difference in colour – hers, by the alchemy of the blue-tinted spotlight, were the colour of Everton toffee, his gleamed, the darkest ebony. She twined about lasciviously, her body moving in rhythm with the pounding drumbeat, naked but for a pink flamingo feather placed between her legs.

The athletic undulations continued as the spotlight followed the black giant to centre stage. Once he’d mastered his astonishment, George decided that what he was seeing was a pas de deux of the highest artistic quality. Yes, that was how he would express it. But he wondered how on earth he could ever convey the shattering erotic charge of the performance and decided never to attempt it. The relentless sound of the drums, the stimulation of the dance and the overriding pressure of the enigmatic presence by his side were beginning to have an effect on George. He ran a finger around his starched collar, harrumphed into his handkerchief and breathed deeply, longing for a lung-ful of fresh air – anything to dispel this overheated soup of tobacco, perspiration and siren scents.

On stage, the dancing pair were writhing to a climax. The giant, at the last, determined to rid himself of his unbearable tormentor, plucked the girl from his back, holding her by the waist in one great hand, and spun her to the floor. He, in turn, collapsed, twitching rhythmically.

‘Thank God for that! Know how you’re feeling, mate!’ George thought and knew that every man in the audience was experiencing the same sensation. He watched, with a smile, for any sign of Alice’s predicted rush for medical attention for the elderly but saw none. To enthusiastic applause and shouts the lights went out, allowing the pair to go offstage, and the curtains swished closed again.

‘Would you like me to loosen your stays, Sir George?’ Alice asked demurely. ‘No? Well, tell me – what do you make of her, the toast of Paris? The Black Venus? La belle Josephine?’

‘Miss Baker lives up to her reputation,’ he said, ever the diplomat. ‘A remarkable performance. I’m glad to have seen it.’

‘And you’re lucky to have seen it. This was the first act she impressed the Parisian public with when she arrived here two years ago. Her admirers have pressed her to repeat it for some time and at last they’ve persuaded her partner – that was a dancer called Joe Alex – to perform with her again. The order of performance, for various reasons, has been changed this evening, you’ll find. Word got out, which is why the theatre is packed tonight.’

‘Is she to reappear?’ he asked, trying for a casual tone. ‘Or have we seen all of Miss Baker that is to be seen?’

‘She’ll be back. Once more in this half – doing her banana dance – and then again in the second. We’re to hear her singing. She has a pleasant voice and an entertaining French accent. Now, George, why don’t you sit back and enjoy the rest of the acts?’

George could well have directed the same question at her, he thought. He felt he could have better entered into the spirit of the entertainment had his disturbing companion herself been at ease. But she was not. He hadn’t been so distracted by the spectacle that he’d failed to notice the tremble of her hand, the bitten lower lip, the anxious glances around the auditorium. Troubling signs in a woman he had always observed to be fearless and totally confident. And if Alice Conyers had no fear of the influential Sir George Jardine with his powers to effect her arrest for deception, embezzlement and murder, culminating in repatriation and an ignominious death on an English gallows, then whom did she fear? He concluded that there must be, lurking somewhere in this luxuriously decadent space – in her perception at least – someone of an utterly terrifying character.

He followed her gaze. Her eyes, under lowered lashes, were quartering the theatre like a hunter. George sighed with frustration. This refurbished and enlarged theatre now housed, on a good night, up to two thousand souls. And of those, all but two were strangers to him. He wondered how many were known to Alice. And in what dubious capacity? Everything he knew of the woman’s past suggested that her associations were likely to be of a criminal nature, after all. And he’d never been aware of a leopard that could change its spots. Good Lord! Could it be that the woman might actually be thinking herself safer in his custody than running loose in Paris? That the grip of his improvised handcuffs about her wrists was not threatening but welcome?

Chapter Four

London, 21st May 1927

Croydon Aerodrome. Gateway to the Empire, the hoarding announced.

‘Arsehole of the Universe, more like,’ Joe Sandilands corrected.

It was fear that, eight years after the war, still reduced him to the swearing and mechanically filthy reactions and utterances of the common soldiery. He looked about him, distracting himself from his terror by examining the other lunatics queuing up to experience three hours of danger and discomfort.

Rich, expensively dressed and unrestrainedly loud, they smiled when they showed their passports and plane tickets, keen to be off. They waved goodbye to their Vuitton luggage, their hat boxes, golf clubs and tennis racquets, as a uniformed employee of Imperial Airways wheeled it all away on a trolley to be stowed in the hold. Joe clutched his Gladstone bag and briefcase firmly when his turn came to face the booking clerk, his steely expression discouraging any attempt to wrest them from him.

‘My luggage has gone ahead. I’ll be keeping these with me,’ he said firmly, flashing his warrant card. ‘Work to do during the flight, you understand.’

‘As long as the light lasts, sir,’ the clerk agreed reluctantly. ‘Will you be requiring supper during the flight, may I ask? I believe we have Whitstable oysters and breast of duck on the menu this evening, sir.’

Joe tried to disguise an automatic shudder. ‘Thank you but I shall have to decline.’ He smiled. ‘Late dinner plans in Paris.’ The reciprocal smile showed complete understanding.

‘Full complement of passengers tonight?’ Joe enquired politely as his tickets were checked and chalk scrawls made on his bags by a second employee.

‘No, sir. By no means. Thirteen passengers. You’re the thirteenth. We can take twenty at a push but the season isn’t in full swing yet. You’ll find it pleasantly uncrowded. Fine clear skies reported over the Channel,’ he concluded encouragingly.

‘This lot must be first-time flyers,’ Joe decided as he shuffled along in file with the chattering group ahead of him to take a temporary seat in a room equipped as a lounge. ‘They won’t be grinning and giggling for much longer.’ One of his friends, like-minded, had summed up the short flight: ‘They put you in a tin coffin and shut the lid. You’re sprayed with oil and stunned with noise. You’re sick into a bag . . . twice . . . and then you land in Paris.’

The passengers, who all seemed to know each other, swirled around the quiet, dark man absorbed by his documents, offering no pleasantries, attempting no contact. Something about the stern face, handsome if you were sitting to the east of him, rather a disaster if you found yourself to the west . . . war wound, obviously . . . kept them at arm’s length. The men sensed an implacable authority, the women glanced repeatedly, sensing a romantic challenge. Everything about him, from the set of his shoulders to the shine on his shoes, suggested a military background though the absence of uniform, medals, regimental tie or any other identifying signs made this uncertain. His dark tweed suit was of fashionably rugged cut and would not have looked out of place on the grouse moor or strolling round the British Museum. The leather briefcase at his feet was a good one though well-worn, and spoke of the businessman hurrying to Paris. But there were disconcerting contradictions about the man. The black felt fedora whose wide brim he’d pulled low over his eyes gave him a bohemian air and the gaily coloured silk Charvet scarf knotted casually about his neck was an odd note and, frankly . . . well . . . a little outré. An artist perhaps? No – too well dressed. Architect? One of those art deco chappies? Bound no doubt for the exhibitions that came and went along the Seine.

Apretty redhead wearing a sporty-looking woollen two-piece and a green cloche hat changed places with one of her friends to sit beside the stranger. She leaned slightly to catch a glimpse of the papers which were so absorbing him. Joe wondered what on earth she would make of the learned treatise he was scanning: Identification of Corpses by G. A. Fanshawe, D.Sc. (Oxon) with its subheadings of Charred Bodies, Drowned Bodies, Battered Bodies . . .

Aware of her sustained curiosity, Joe mischievously shuffled to the top a printed sheet of writing paper. Under the bold insignia of Interpol, and laid out in letters so large she would have no difficulty in reading them, was an invitation to The Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Scotland Yard, London, to attend the second conference of Heads of Interpol in Paris. A detailed programme of lectures and events followed. Joe took out a pencil and began to make notes in the margin.

She addressed him with the open confidence of a fellow passenger aboard a boat, all companions for the duration of the voyage. ‘I see you’re not on pleasure bent in the capital of frivolity? Er . . . Commissioner? Should I address you as Commissioner? Is that who you are?’

He grinned and passed her a card. ‘Not Commissioner, I’m sorry to say. He’s the villain who’s deputized me to come along in his stead. This is me. I’m Joseph Sandilands. How do you do, Miss . . .?’

‘Watkins. Heather Watkins.’ And she read: ‘Commander Sandilands. DSO. Légion d’honneur. Ah, I was right! I took you for a military or naval man of some sort. But Commander sounds very impressive!’ And she added in a tone playfully inquisitive: ‘May we look to see “Commissioner” on your card one day?’

‘I do hope not! Annoying my boss is one of my chief recreations. I should hate to find myself at the top of the pyramid keeping order. Who would there be to keep me in order? I should have to do it myself!’ Good Lord! That was the first time he’d given words to any such feeling. And he’d expressed it in unbelievably artless words to a complete stranger. It must be the fear of the next few hours that was sweeping away his defences, making him reckless.

The arrival of a steward in Imperial Airways livery made unnecessary any further revelations and they were called for boarding. The group, jostling and joking with each other, surged forward. But, at the point of putting her foot on the ramp, the lively and confident Miss Watkins, who had trailed behind finishing a conversation with Joe, balked. She shook her head like a horse refusing a fence, turned pale and began to breathe raggedly. Joe, close behind, recognized the symptoms and put a comforting arm under hers. ‘Don’t worry,’ he said. ‘And, above all, don’t be concerned if the wings appear to wobble alarmingly. They’re supposed to do that. Watch them carefully and, should they stop wobbling, then you may start to worry. These big planes are perfectly safe, you know, and the company has an unblemished record. Look – do you see – it’s an Argosy. That means it’s got four wings, three engines and two pilots. That should be enough to get us through.’ He wished he could believe all this rot himself. ‘And, look, Miss Watkins . . . Heather . . . take this. I find it really helps.’ He passed her a lump of barley sugar.

A second steward in spanking white mess jacket and white peaked cap welcomed them aboard what he proudly called ‘the Silver Wing service’ and, taking them for a couple, ushered them towards a pair of seats alongside at the rear of the plane.

‘Every passenger has a window seat, you see,’ said Joe, helping her to settle. ‘Though you can always draw the curtain across, should you have vertigo.’

They braced themselves for take-off. It came with the usual terrifying snarls of the engine and bumps along the runway and then there was the stomach-clenching moment of realization that the machine had torn itself free of the earth and was soaring at an impossible angle upwards. A glance through the oil-spattered glass showed the grey blur of London disappearing below them. Higher up, the sunlight brightened and they caught the full glow of the westering sun gilding the meadows and woods of southern England.

‘It will be dark before we arrive, won’t it?’ Heather Watkins asked, suffering a further pang of apprehension.

‘Yes,’ Joe admitted. ‘This is technically the night flight, after all. We should touch down just before ten o’clock.’

‘But how will the pilot . . .?’ Hearing the naïveté of her question, Heather fell silent.

‘Beacons all the way along the flight route,’ said Joe confidently. ‘But while the light lasts, he’ll just follow the railway lines. Look – over there!’ He pointed out a group of buildings below. ‘You can see exactly where we are. Do you see – it’s Ashford. That was the railway station. They paint the names of the main stations on the roof in big white letters all the way to Paris. They have emergency landing strips every few miles. And even in the dark the pilot can’t mistake the Eiffel Tower. It’s lit like a Christmas tree!’

Miss Watkins checked every few seconds to see that the wings were wobbling satisfactorily, the railway lines still beneath them, and finally began to relax.

‘Doing anything interesting in Paris?’ Joe asked when he judged she was capable of a sensible reply.

‘Oh, the usual things,’ she said. ‘Shopping and shows for a few days then we’re all off to the south of France. For the tennis tournament.’ She fell silent.

‘Do you observe or compete?’ he asked.

‘Oh, I play. Not very well. I mean I’m not in the Suzanne Lenglen or Helen Wills league yet but I’m improving. The boys,’ she indicated the four young men sitting ahead of them, ‘are all players. My brother Jim – that’s him with the red hair – is the team captain and general organizer. The other two girls are team wives. I’m the odd one out.’

‘Very odd,’ Joe agreed. ‘Most unusual. I’ve never met a lady tennis player before. One who plays seriously.’

‘There aren’t many of us in England. In France it’s thought rather dashing and quite the okay thing to be! We’re even allowed to wear skirts up to our knees over there.’

She rummaged in her handbag. ‘Look – here’s where we’re staying . . . well, you never know. It’s a little hotel on the Left Bank. In the rue Jacob. Handy for the bookshops. And a stone’s throw from the police headquarters, funnily enough . . .’ she added with a gurgle of laughter. ‘It’s right opposite the Quai des Orfèvres!’

‘I’m booked in at the Ambassador on the Right Bank, handy for the Opéra,’ he said lightly. ‘And a few steps away from the department stores. Au Printemps . . . Galeries Lafayette, funnily enough . . . One way or another, I think it’s very likely in the way of business or pleasure our paths will literally cross again. And if my mental map of Paris serves me well, that’ll be just about at Fauchon’s, Place de la Madeleine. In time for what they call “the five o’clock tea”.’

So that was the way to conquer a fear of flying – sit yourself next to a beautiful, athletic redhead and flirt your way there – Joe thought as they began to circle Paris, preparing to land at Le Bourget airfield just to the northeast. He wished he’d suggested something a little less staid than a salon de thé. The Deux Magots in St Germain would have struck a more adventurous note. Well, it was just a few stops on the electric tram and taxis were everywhere.

‘How are you getting in to the city?’ Joe asked. ‘It’s quite a few kilometres distant . . .’

‘Oh, Jim’s ordered a couple of taxis. You?’

‘A colleague from the Quai des Orfèvres is coming to collect me. In a police car, I expect,’ said Joe. ‘All screeching sirens and flashing lights – that would be his style!’

He smiled at the mention of his colleague and relished the thought of the warm greetings they would exchange. Inspector Bonnefoye. Late of Reims. Now, thanks to his undeniable talent and his great charm, promoted to the Police Judiciaire squad in Paris. A useful contact. Relations between the English and the French police departments were not often easy. Joe had made known his plans for attending the conference and Bonnefoye, with Gallic insouciance, had set about pulling strings and calling in favours, making promises – who knew what? – to get himself appointed to the French contingent at the Interpol jamboree. Not that Bonnefoye seemed prepared to take it seriously. His telephone conversations had been full of plans of an entertaining nature which had little to do with international crime fighting.

The Argosy circled the Eiffel Tower, Joe judged for the satisfaction of the passengers rather than in response to any navigational imperative, then headed off to the northeast and lined itself up, head into the wind facing an illuminated landing strip, and made a delicate touchdown. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief.

It was the stewards’ odd behaviour that warned Joe. Suddenly unconfident, they advised the passengers to remain seated: ‘. . . until we have taxied up to the hangar. There appears to be an impediment on the runway,’ one of them improvised. The other climbed the stairs communicating with the cockpit to confer with the crew and he returned looking no less puzzled. The doors remained closed. No staff came forward to open the door and release them. And something was going on outside the plane.

Peering through the gloom, Joe saw, to his astonishment, shadows moving on the tarmacked runway, lights from torches and flares skittering everywhere. The passengers sat on, docile and puzzled.

Joe got to his feet and, with a calming gesture to the two stewards, made his way down the gangway to the front of the plane. With a bland smile he murmured: ‘I speak a little French.’ They nodded dubiously and made no attempt to remonstrate with him. No one ever challenged a man confident enough to make such an assertion on foreign soil, he found. He nipped up the steps and located the two pilots seated in the open cockpit.

‘Captain! Commander Sandilands here. Scotland Yard. What’s the problem?’

‘Problem? I’ll say!’ came the shouted reply. ‘People! It’s worse than a football crowd. Look at them! They’re standing ten deep up there on the viewing gallery. And they’re milling around everywhere, all over the runways. Damned dangerous, if you ask me! And where are the airport staff? Can’t move until they’ve cleared this mob away. What the hell’s going on? Some strange French Saturday night entertainment?’

‘Oh, no!’ Joe groaned. ‘I think I can guess what’s going on. It’s Charles Lindbergh! Attempting the transatlantic crossing. It was on the wireless – he was sighted over Ireland this afternoon. Made much better time than anyone expected and I’d guess this mob’s gathered to watch him land. We must have beaten him to it by a few minutes. Dashed inconvenient! And we’re a huge disappointment to all these idiots on the runway. It’s not us they’ve come out from Paris to see. Ah, look! At last – they’ve twigged. They’re pushing off, I think. They’ll leave us alone now.’