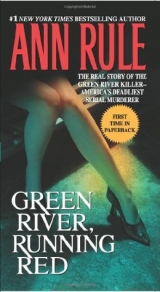

Текст книги "Green River, Running Red. The Real Story of the Green River Killer - America's Deadliest Serial Murderer"

Автор книги: Ann Rule

Жанр:

Маньяки

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

12

THREE DECADES LATER in Seattle, 1983 lay just ahead. Few were sad to see the old year end. It had been a terrible time for a lot of people, but an exceptionally newsworthy era. In January 1982, Wayne Williams had been convicted of killing two of twenty-eight murdered black children in Atlanta. Claus von Bülow was found guilty in March of the attempted murder of his wife, heiress Sunny von Bülow, who went into a permanent vegetative state after he allegedly injected her with an overdose of insulin. (His conviction was later overturned.) Comedian John Belushi died of a combination of speed and heroin that same month. In happier news, Princess Diana gave birth to her first son, William, in June. But Ingrid Bergman died of cancer in August, and Princess Grace of Monaco drove off a cliff in September, suffering fatal injuries. In October, Johnson & Johnson took Tylenol off the market after eight people were fatally poisoned by strychnine-laced capsules. Pierce Brooks had flown to Chicago to try to help in that investigation. The Excedrin poisoning case was still open in Kent, although it didn’t get much national media play.

It got a lot more, however, than the Green River Killer cases, which were virtually unknown beyond Washington and Oregon. They had gripped Northwest residents and captivated the regional media, but nothing seemed to be happening in terms of an arrest or charges that would lead to a trial—or trials.

FRESH AIR, views of Elliott Bay, and even windows had never been perks for detectives in the King County Sheriff’s Office. Their offices were located on the first floor of the King County Courthouse, an antique building with marble hallways and a foundation so shaky that structural engineers warned that a substantial earthquake could bring it tumbling down. Major Crime Unit investigators’ desks filled one big room and the overflow was squeezed into small side rooms that held only three supervising officers. Command officers had offices, but they were tiny and had no windows either. Rooms where suspects were questioned were cramped.

Now, the Green River Task Force met in the same hidden space in the King County Courthouse where the “Ted” task force had worked back in the midseventies. Its narrow war room was across the hall from the Narcotics Unit, both half a floor up the back stairs at Floor 1-A. Two detectives could barely stand side by side with their arms outstretched without bumping into the walls. About the only thing 1-A had going for it was that it was private; no outsider could approach it without being stopped.

Maps and charts and victims’ photographs were tacked on the walls. Stacks of paper piled up, waiting to be sorted. The phones rang constantly. It was a “boiler room” in every sense of the term.

Fae Brooks and Dave Reichert were fielding most of the calls that were coming in. Reichert still looked as if he were in his early twenties; he grew a small mustache that made him look only slightly older. Most people close to the sheriff’s office still called him Davy, because it fit him.

Fae Brooks had made her bones in the sex crimes unit. She was a slender, classy black woman with a café au lait complexion. Intelligent and soft-spoken, she wore the big spectacles that were popular in the early eighties.

Some of the phone calls they answered were from anxious families or boyfriends of young women who hadn’t been heard from. More were from tipsters who were sure their information was vital. There were dozens and dozens of calls, and trying to respond to them all and even hope to follow up was like putting one finger in a dike that threatened to burst at any moment.

A number of tips and referrals were impossible to say “yes” or “no” to in terms of their possible connection to the Green River Killer. In late January 1983, a man laying water pipes along a shallow ditch only a hundred yards from Northgate Hospital was removing some brush when he was horrified to see what appeared to be a human skeleton beneath the branches. The location was almost on the north Seattle boundary line, so it was handled by the Seattle Police Department.

The desiccated remains were of a small human. The King County Medical Examiner’s office removed the bones carefully, but an autopsy failed to reveal any cause of death. The body had no soft tissue left; the young female could have died from any number of causes.

The teeth, however, matched Linda Jane Rule’s, the blond girl who had been missing for four months after she left her motel room to walk to the Northgate Mall. Sergeant Bob Holter and Captain Mike Slessman of the Seattle Homicide Unit were fully aware of the Green River murders, but they could find no absolute link between them and Linda Rule. Lifestyle? Yes. Location? Not really. Most of the missing women had last been seen in the south county area, not in the north end. “Technically,” Holter said, “we’re not calling this a murder—we don’t have enough to go on for that—but the results are the same. She is dead, and we don’t know why or how.”

BY early March 1983, the dread that there was still someone out there on the highway grew. The women who fell into the endangered category counted the possible victims and had to fight back panic. Still, almost all the young women who worked the SeaTac Strip or along the dangerous blocks on Aurora Avenue North believed that they would be able to recognize the killer. He must surely be giving clues that the missing girls hadn’t picked up on. Each working girl had a picture in her mind about who she would not go with. Many of them worked on the buddy system with other prostitutes, saying “Remember who I’m with” as they got into cars. Some would not accept car dates, others wouldn’t go into a man’s motel room, or his house.

ALMA ANN SMITH was working the corner of S. 188th Street and the highway on March 3, 1983. The huge and expensive Red Lion Inn was located there, across the street from the airport. This was no “hot bed” motel; the Red Lion was one of the nicer places to stay in Seattle, with its richly carpeted corridors, hand carvings, and exterior elevators that echoed the Space Needle’s. There was a pricey gourmet restaurant on the Red Lion’s top floor. If the Green River Killer was scruffy-looking, he would be noticed immediately at the Red Lion and quickly hustled outside by hotel security.

Alma came from Walla Walla, Washington, a world away from Seattle. Brook Beiloh, her best friend in seventh grade, remembered her as an extremely generous girl who “didn’t have a malicious bone in her body.”

Brook recalled the childhood days they had shared. “Walla Walla was still untouched by crime twenty years ago. Kids played in the streets till dark. We rode our bikes to every corner of that small town without fear and without supervision. This was the place where a latchkey kid didn’t need a key because who locked their doors? After seventh grade, I didn’t see Alma very often. She would be in class one day, and then you wouldn’t see her again for three to six months. When she came back from wherever she went—or maybe ran away to—she always made an effort to contact me. We would hang out for a day or two, and then she’d be gone. I don’t know the story behind this behavior, although I asked her one time where she always took off to, and she simply replied, ‘Seattle.’ Alma was a couple of years older than me, but I still remember thinking how terrifying it would be to be alone in the city!”

Once, Alma sent Brook an eight-by-ten picture of herself, a studio shot, with a letter on the back. Alma’s hair was blonder than when she was in the seventh grade, but she still had great eyes with arching brows. “I don’t know where she got it, because Alma never had a lot, so this gesture touched me deeply,” Brook recalls. “I saw her last in December 1982, just three months before she was murdered.”

Alma had a lot of friends, and she and some of the other girls who plied their risky trade along the Strip agreed to try to protect each other. Alma and her roommate and best friend, Sheila,* were both looking for johns on March 3. Sheila left with a man first, returning to the bus stop about forty-five minutes later. Alma wasn’t there, and Sheila figured she’d found a trick.

“Anyone know where Alma went?” she called to young women nearby.

“She left with some guy in a blue pickup truck.”

“White or black?”

“White—just an average-looking guy. You know…”

Sheila grew concerned when an hour passed and Alma didn’t come back. She had a “hinky” feeling, but she couldn’t say why. She wished she had been there to get a license number or something. She waited nervously for Alma to come back.

Alma never did.

DELORES WILLIAMS was another girl who found the bus stop in front of the sumptuous motel a good place to meet wealthy johns, and to take shelter from the rain, too. Delores had a lovely smile, and she was tall and slender. She was only seventeen. The storms of March whipped and keened around the towering wings of the Red Lion, and the bus stop with its partial paneling was cold, but business was usually brisk.

Still, by March 8, Delores didn’t wait there any longer. Her friends thought maybe she’d found a better location.

BOTH DAVE REICHERT and Fae Brooks still felt that Melvyn Foster was a good suspect. It was hard for them to write him off because he had, it turned out, known some of the first six victims, however briefly. And he did fit into the part of the John Douglas profile about suspects who liked to hang around the investigation and savor their memories. Foster continued to brag that he’d be glad to punch the killer out if he ever ran across him, and claimed that the police were wasting time concentrating on him when they should be out looking for the real killer.

Dick Kraske could see that two detectives couldn’t possibly keep up with the overload, and he transferred four more investigators in to help: Elizabeth Druin, Ben Colwell, Pat Ferguson, and Larry Gross. Detective Rupe Lettich, who had been the head narcotics detective in King County for a long time, was right across the hall and he helped, too. But the twenty-five-person task force was no more. Morale was low and the public didn’t seem to care all that much about young prostitutes out on the SeaTac Strip. They weren’t their daughters.

But silently and stealthily, more of them were being trapped like rabbits in a snare.

Spring arrived with daffodils, tulips, cherry blossoms, and Scotch broom bursting as they always have from rain-sodden earth. Hopes, however, did not. The girls who had gone missing in the fall and winter apparently weren’t in Portland or Yakima or Spokane or any other city on “the circuit.”

SANDRA K. GABBERT was seventeen on April 17 when she strolled along the Strip near what appeared to be the most dangerous corner—Pac HiWay and S. 144th. The Church by the Side of the Road was three blocks away, the 7-Eleven was a block away, and the motels that catered to four-hour occupancy for only $13 and cheap weekly rates were clustered around that intersection. Although she’d been a star on the girls’ basketball team, Sand-e had dropped out of school because she was bored, and now she was living with her teenage boyfriend. They were barely able to afford motel rooms and fast food. Her mother, Nancy McIntyre, knew that Sand-e was selling herself to make enough money for that, but she couldn’t stop her. Sand-e’s street name was “Smurf,” and she had a kind of insouciant charm, as if she didn’t take herself all that seriously.

Maybe Sand-e didn’t remember where the other girls had vanished, or maybe she didn’t care. She had the untested confidence common to the young; she was indestructible.

Nancy had been on her own with Sand-e since her divorce when her little girl was two. Only forty-one, Nancy had worked as a bar-maid for years and life was tough. Now she made minimum wage as a maintenance worker for the Seattle Parks Department. She didn’t even try to debate the moral issues of prostitution with Sand-e; she was worried about her daughter’s survival. “I said, ‘Sand-e, you could get yourself killed doing this,’ and she said, ‘Oh Mom, I’m not going to get killed.’ She didn’t want to hear about it or talk about it because she knew I was so scared. She could turn one trick, take half an hour, and make as much as she made when she worked for Kentucky Fried Chicken for two weeks. Now, you try to show someone the logic of getting a legitimate job,” Nancy said with a sigh. “I realized if I tried to force her to stop, I’d have alienated her from me. And I’d go through anything before that—even prostitution.”

The last time Nancy saw Sand-e, they ate at a Mexican restaurant, and Sand-e talked about her plans to go traveling to San Francisco and Hollywood. “I put my arms around her,” Nancy recalled as tears coursed, unbidden, from her eyes. “I said, ‘I love you, baby. Please be careful.’ She said, ‘I love you, too. I am careful.’ I watched her walk along the front steps, and I knew I wasn’t going to see her for a long, long time.”

Four days later, Sand-e was gone.

WITHIN only a few hours, Kimi-Kai Pitsor, who was sixteen, got into an old green pickup truck on 4th and Blanchard in downtown Seattle. By taking the I-5 Freeway, it was possible to travel the fourteen miles between the two locations in under half an hour, unless someone tried to do it during rush hour when traffic backups were the norm.

Could the same man have taken both teenagers in one night? Bundy had taken two victims on one Sunday afternoon eight years earlier. But those young women were sunbathing at the same park. Was it imaginable that this man was trying to break some dark record?

Kimi-Kai and Sand-e looked somewhat alike, youngish for their age, with dark hair and bangs. Sand-e had been alone just before she disappeared, although she and her boyfriend had walked together to the 7-Eleven only a few minutes before. She had left him behind as she crossed Pac HiWay. And Kimi-Kai was walking with her boyfriend/protector when she signaled a man in a truck to turn around the corner so she could get into his vehicle without being seen.

Kimi-Kai, whose street name was “Melinda” had tried working down in Portland for a short time, but the girls there pegged her as “very innocent and naive.” With her boyfriend, she had headed for Seattle, along with several other young women who’d been in Portland, because the word was you could make more money there. But the word was wrong; Portland wasn’t where it was happening. So they returned to Seattle.

For the second time, detectives had the description of a vehicle (beyond the small white car Barbara Kubik-Patten said she saw by the Green River). Again, it was a pickup truck. Kimi-Kai’s boyfriend described an older green truck with a camper on the back and primer paint on the passenger door. He thought it was either a Ford or a Dodge.

Halfway into April 1983, and two more teenagers had failed to come back or to call anyone they knew. The trucks’ descriptions were printed in Seattle papers, but the investigators weren’t too hopeful that it would help. There were a lot of older trucks, some of them green, some blue, some brown and tan, and a whole lot of them with primer spots.

FOR SOME REASON murder victims and most serial killers are often referred to in the media by their first, middle, and last names. Is it, perhaps, to give the victims dignity? As for the killers, is it to distinguish them from other men with similar names? Or does it, unfortunately, imbue them with extra infamy? Theodore Robert Bundy, Coral Eugene Watts, Jerome Henry Brudos, Harvey Louis Carignan, John Wayne Gacy.

Hearing the full names of the hapless teenagers who encountered the Green River Killer could not help but evoke thoughts of how short a time had passed since they were tiny babies, whose parents lovingly picked out enchanting names, with carefully chosen middle names, in the hope that their daughters’ lives would unfold like flowers. Even parents whose own lives had been bruised with disappointment hoped for a better future for their children.

Kimi-Kai Pitsor’s mother, Joyce, loved her baby’s name so much that she embroidered it on her sheets and blankets. In Hawaiian, it meant “golden sea at dawn.”

Talking with veteran Seattle Post-Intelligencer reporter Mike Barber, Joyce Pitsor described Kimi-Kai as a petite girl who loved unicorns and anything purple. Like many girls her age, she hit a defiant streak almost at the very moment she entered puberty. She fell in love with a boy and wanted to be with him more than her mother thought prudent. Railing against curfews and rules, Kimi left home in February 1983 to move in with her boyfriend, but she called her mother every week.

“Kimi was very adventurous,” Joyce remembered. “She wasn’t afraid. She wanted to see how life worked and never took anyone’s word for anything. She had to see for herself. I remember telling her, ‘Be a little girl for a while. Enjoy yourself. You have all the time to be a grown-up with all those problems.’ But she wanted to be an adult so bad.”

And now, Kimi-Kai was gone. If anyone had ever viewed her as tough, her mom knew better. “She could put on the most bravado routine, especially if she was terrified. What it really was was bordering on hysteria.” Joyce Pitsor had seen that when she rushed down to juvenile court to stand by Kimi-Kai when she was in trouble.

Now, waiting for word was torturous for her mother, who had already lost two of her children—one at birth and one as an infant. She was a woman who loved kids; she had adopted three biracial children because she did care so much. But she hadn’t been able to convince her own daughter to wait just a few years before she plunged into the adult world.

And within only two months of “freedom,” Kimi-Kai was gone, too.

THE NEW WEST MOTEL was on the Des Moines end of Pac HiWay across 216th to the north of the Three Bears, with a convenience store between them.

SOMETIME in the third week of April, Gail Lynn Mathews, twenty-four, registered at the New West. Gail was an exotic-looking woman with luxuriant black hair. Her most distinctive feature was her extremely full, lush mouth. She was living with a thirty-four-year-old man from Texas named Curt, whom she’d met at Trudy’s Tavern near the airport in 1982. At that time, she’d had a little apartment across from Trudy’s, but she lost it when she couldn’t make the rent in February 1983. For weeks after that, Gail lived a week or two at a time with friends of friends of friends.

Except that she was older than most of the Green River victims, Gail Mathews’s lifestyle was similar to theirs. She had been married, but she was either divorced or separated by the spring of 1983, and she was down on her luck.

Neither Gail nor Curt had much money or permanent jobs; they drifted while he gambled in card rooms and she nursed a beer in the bar, waiting to see if he’d win enough for a meal and motel. Curt’s extensive vocabulary reflected his intelligence and education, but either drugs or alcohol had sidetracked him. His regular haunts were the White Shutters, Trudy’s, and the Midway Tavern. Now and then, Gail contributed money to the kitty. She never told Curt where she got it, and he never asked. Their lives had become a day-to-day existence. They had no car and no permanent residence.

On the last night Curt saw Gail, things were normal—for them. They had stayed in the New West for a few days, but their rent was up and they were both broke. On the night of April 22, they were in the VIP Tavern a few blocks north of their motel. They shared a couple of beers while Curt played Pac Man. Gail watched him, not talking to anyone else in the tavern.

Finally, Curt decided to head to the Midway Tavern, which was across the Kent–Des Moines Road from the Texaco station and the Blockhouse Restaurant. He hoped they had a poker game going there, and he’d have a lucky night.

Gail told him she would try to find a way to keep their motel room for another night or two. He walked away from the VIP Tavern, leaving her there alone; she knew the woman bartender. It was more than a mile to the Midway, so Curt decided to catch a bus. He waited at the familiar intersection at 216th and the Pac HiWay. Idly, he watched traffic and noted a blue or possibly green Ford pickup passing. It wasn’t new by any stretch of the imagination, but it was noticeable because it had so many sanded “circular” marks on it, as if it was primed for a paint job.

Curt was startled to see Gail sitting in the passenger seat beside a man with light hair who appeared to be in his early thirties. He was wearing a plaid shirt that made him look like an “outdoorsman.”

Curt’s arm was half lifted to wave at Gail when he was surprised by the way she looked. “She seemed dazed,” he would tell F.B.I. agent “Duke” Dietrich later. “She was staring straight ahead. It was bizarre. She was looking right at me, but it was as if she didn’t see me. I’m sure she could see me—it wasn’t dark out yet.”

He waved harder, but Gail didn’t respond. If she was trying to signal him that she was in some kind of trouble, he couldn’t decipher it. She was sitting far away from the driver, right next to the passenger door. He watched as the truck turned left and disappeared. “I don’t know how to explain it,” Curt said, “but I felt fear—fear for her because I sensed she was in danger. I ran across the road toward the truck and tried to catch up with it, but the driver made a left turn and sped up.”

Curt had watched helplessly as the truck disappeared. The bus came by and he got on, telling himself that he was overreacting. He spent an hour at the Midway Tavern, but nobody wanted to play poker, so he trudged back to their motel room. He watched the highway for a long time, waiting for car lights to turn into the motel or the sound of Gail’s footsteps scrunching the gravel. There were a few cars, but Gail didn’t come back that night.

Curt called 911 to report her missing. He said later that he was told that he couldn’t make an official missing person’s report because he was not related to her.

Curt waited for Gail to come back or leave a message for him at the motel office, but there was nothing. He stopped at all the places along the highway where they’d gone together. No one remembered seeing Gail recently. He couldn’t help it; his mind turned to thoughts about the Green River Killer. Both he and Gail were aware of the missing and murdered girls, but she had never been afraid. He’d warned her about hitchhiking, too, but she told him not to worry about that—she could take care of herself.

He wondered now why Gail had looked so strangely at him—or, rather, through him—when he waved at her. Somehow, the man behind the wheel must have been controlling her. Maybe he was holding a knife against her body so she didn’t dare cry out. Maybe a gun. Why else would she have not even waved or smiled at him?

They’d been together for almost a year, and they’d become close. Curt didn’t buy the idea that Gail would simply leave him with no explanation. It was true they hadn’t had much money, and life was tough for them, but they had always believed that if they pulled together, they could get out of the hole they were in and build a better life. But drugs were important to Curt, too, and eventually he moved on, unsure of what had happened to Gail.

By the time an investigator knew what had become of Gail and tracked Curt down, he was an inmate in a Texas prison. When he was returned to Seattle to be interviewed by Dr. John Berberich, the Seattle Police Department’s psychologist, Curt agreed readily to be hypnotized. Maybe there was something hidden in his subconscious that would help catch her killer. A license number or a more complete description of the truck and driver.

Despite their best efforts, Curt could recall nothing beyond the odd, frozen look on Gail’s face the last time he saw her.

EIGHT DAYS after Curt saw Gail Mathews in a stranger’s truck, that same intersection was the scene of an apparent abduction. Marie Malvar was eighteen, a beautiful Filipina, the cherished daughter of a large family. They didn’t know she was out there on the highway at S. 216th, near the Three Bears Motel, trusting that she was safe because her boyfriend, Richie,* was with her to note which cars she got into and to make sure she came back safely in a reasonable time.

The young couple watched as a dark truck approached the intersection from the south. As it pulled over, they could see a spot on the passenger door that glowed lighter than the rest of the truck, a coat of primer paint. Marie spoke to the driver, nodded, and then got in and the stranger’s vehicle pulled onto the highway again.

As he usually did, Richie followed, keeping pace, and then pulling alongside. From her gestures, it appeared to him that Marie was upset. He couldn’t hear what she was saying, but it looked as though she wanted to get out of the truck. The driver slowed down, but only to turn around in a motel parking lot and then accelerated as he headed south. Richie did the same, but he didn’t make the light at S. 216th. It turned red and he had to stop. He watched as the pickup truck turned left and headed east—in the direction of the Green River. As soon as the light changed, Richie turned left, too.

Because he was less than a minute behind the pickup, Richie thought it was strange when he saw no taillights ahead, neither going down the Earthworks hill on 216th, nor headed north or south on Military Road, which ran parallel to the highway. Tossing a coin in his head, he drove south on Military, but there were no vehicles at all between the intersection and the Kent–Des Moines Road a few miles south. There didn’t seem to be anyplace the truck could have turned off, because Military and the I-5 Freeway were so close together and there were no on-ramps along that section.

Richie didn’t see the almost invisible street sign that led to a narrow cul-de-sac on the right side of Military Road. It was easy to miss, especially in the dark. Bewildered, he drove back to the parking lot to wait for the guy in the truck to bring Marie back.

But he never did.

Because he and Marie had been engaged in prostitution, Richie was hesitant to go to the police. He was just as nervous about telling her father, Jose, because he feared his wrath when he learned that Richie had let Marie take such chances. Still, when four days went by with no word from her, Richie went to the Des Moines Police Department. There, he talked to Detective Sergeant Bob Fox. Richie reported Marie as missing, but he didn’t tell the whole truth about what he and Marie had been doing out on the highway. If he had, Fox, who had investigated many homicides in the city of Des Moines, and who was well aware of the Green River cases, would have reacted differently. Instead, Richie’s evasiveness made Fox wonder if he hadn’t harmed his girlfriend himself, or, more likely, Marie Malvar and Richie might have had a fight and she’d left him on her own.

Jose Malvar was very concerned. Marie wasn’t a girl who stayed away from home for long, and she called frequently. Now there was only silence. Jose picked up Richie and said they were going to find her, demanding to know just where she and Richie had been when she disappeared.

Jose, Richie, and Marie’s brother, James, started at the intersection where Richie had seen the pickup truck pull away. They inched east on 216th, down the long winding hill, and then back and forth along Military Road. They were looking for some sign of Marie, or the truck with the primer spot on the passenger door. They checked driveways and carports. There weren’t many houses on the west side of Military Road going north—only a new motel sandwiched in a narrow slice of land just off an I-5 Freeway ramp. But when they headed south, there were many modestly priced homes on both sides of the road.

On May 3, the trees were all leafed out and dogwood, cherry, and apple trees were blooming. After making several passes, they finally spotted a street sign on the right side of the road: S. 220th Place. Turning in, they found an almost hidden residential street, a cul-de-sac with eight or ten little ranch houses. In the driveway of a house near the north end of the street, they all saw it: an old pickup truck. They got close enough to look at the passenger door. It had a primer splotch on it.

They immediately called the Des Moines Police Department, and Bob Fox responded. He and another detective knocked on the door while Marie’s father, brother, and boyfriend watched. Fox was talking to someone, nodding, asking another question, and nodding again. Finally, the front door shut and the Des Moines detectives walked slowly down the walk.

“He says there’s no woman in there,” Fox told Jose Malvar. “Hasn’t been a woman in there.”

The man who said he was the owner had struck the police as straightforward enough, and he hadn’t been nervous, just curious about why the police were knocking on his door. Fox didn’t even know if his was the same truck Richie had seen, and he hadn’t pushed his questioning very hard. There was no probable cause to search the small house whose rear yard backed up to the bank that sloped to the freeway. The guy who lived there was friendly but firm when he said he lived there alone, had just bought the house, in fact.

Her boyfriend and relatives who were searching for Marie Malvar watched the house for a while, frustrated and anxious. Was Marie in there? Had she ever been? They fought back the urge to go up and pound on the door themselves, but, finally, they drove away. Still, they came back at odd times to check. It was the closest they could be to Marie, or at least they thought so. Where else could they look?

DETECTIVES were inclined to believe that none of the men who had driven battered pickup trucks was likely to be the killer they sought. With both Kimi-Kai Pitsor’s and Marie Malvar’s last sightings, the girls’ boyfriends were positive that the drivers had seen them watching. It didn’t make sense that a killer would be brazen enough to take that kind of chance. It was more likely that Kimi-Kai and Marie had met someone else after they got out of the trucks.