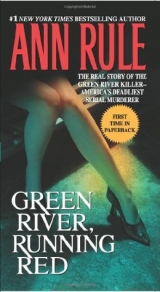

Текст книги "Green River, Running Red. The Real Story of the Green River Killer - America's Deadliest Serial Murderer"

Автор книги: Ann Rule

Жанр:

Маньяки

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

Also by Ann Rule

Heart Full of Lies

Every Breath You Take

…And Never Let Her Go

Dead by Sunset

Everything She Ever Wanted

If You Really Loved Me

The Stranger Beside Me

Possession

Small Sacrifices

Kiss Me, Kill Me

Without Pity

Last Dance, Last Chance

Empty Promises

A Rage to Kill

The End of the Dream

In the Name of Love

A Fever in the Heart

You Belong to Me

A Rose for Her Grave

The I-5 Killer

The Want-Ad Killer

Lust Killer

FREE PRESS

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright © 2004 by Ann Rule

All rights reserved,

including the right of reproduction

in whole or in part in any form.

FREE PRESS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Designed by Karolina Harris

Library of Congress Control Number: 2004056338

ISBN-13: 978-0-7432-7641-2

ISBN-10: 0-7432-7641-8

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.Simonandschuster.com

In memory of all the lost and murdered young women who fell victim to the Green River Killer, with my profound regret that they never had the chance to make the new start so many of them hoped to achieve.

Introduction

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Part Two

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Part Three

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Afterword

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Cast of Characters

THE VICTIMS, IN ORDER OF THEIR DISAPPEARANCE

Wendy Lee Coffield, Debra Lynn Bonner, Cynthia Jean Hinds, Opal Charmaine Mills, Marcia Faye Chapman, Giselle Lovvorn, Terry Rene Milligan, Mary Bridget Meehan, Debra Lorraine Estes, Denise Darcel Bush, Shawnda Leea Summers, Shirley Marie Sherrill, Colleen Renee Brockman, Rebecca Marrero, Kase Ann Lee, Linda Jane Rule, Alma Ann Smith, Delores LaVerne Williams, Sandra Kay Gabbert, Kimi-Kai Pitsor, Gail Lynn Mathews, Andrea M. Childers, Marie Malvar, Martina Theresa Authorlee, Cheryl Lee Wims, Yvonne Shelly Antosh, Constance Elizabeth Naon, Carrie Ann Rois, Tammy Liles, “Rose,” Keli Kay McGinness, Kelly Marie Ware, Tina Marie Thompson, Carol Ann Christensen, April Dawn Buttram, Debora May Abernathy, Tracy Ann Winston, Maureen Sue Feeney, Mary Sue Bello, Pammy Avent, Patricia Anne Osborn, Delise Louise Plager, Kimberly Nelson, Lisa Lorraine Yates, Cindy Ann Smith, Mary Exzetta West, Patricia Michelle Barczak, Patricia Yellow Robe, Marta Reeves, Roberta Joseph Hayes, Jane Doe C-10, Jane Doe D-16, Jane Doe D-17, Jane Doe B-20.

VICTIMS LATER ELIMINATED AS

GREEN RIVER KILLINGS

Leann Wilcox, Virginia Taylor, Joan Conner, Theresa Kline, Amina Agisheff, Angelita Axelson, Patty Jo Crossman, Geri Slough, Oneida Peterson, Trina Hunter.

THE INVESTIGATORS: 1982 THROUGH 2004

Green River Task Force Commanders: Dick Kraske, Frank Adamson, Jim Pompey, Bob Evans, Mike Nault, Jim Graddon, Bruce Kalin, Terry Allman.

Green River Investigators: Sheriff David Reichert, Lt. Greg Boyle, Lt. Jackson Beard, Lt. Dan Nolan, Sgt. Harlan Bollinger, Sgt. Rupe Lettich, Sgt. Frank Atchley, Sgt. Bob “Grizzly” Andrews, Sgt. Ray Green, Sgt. Ed Streidinger, Sgt. D. B. Gates, Sue Peters, Tony McNabb, Bob Pedrin, Bob LaMoria, Fae Brooks, Ben Colwell, Elizabeth Druin, Larry Gross, Tom Jensen, Jim Doyon, Bruce Peterson, Ralf McAllister, Nancy McAllister, Spence Nelson, Pat Ferguson, Ed Hanson, Chuck Winters, John Blake, Carolyn Griffin, Mike Hagan, Rich Battle, Paul Smith, Rob Bardsley, Mike Hatch, Jerry Alexander, Ty Hughes, Randy Mullinax, Cherisse Luxa, Bob Gebo, Matt Haney, Kevin O’Keefe, Jake Pavlovich, Raphael Crenshaw, Katie Larson, Jon Mattsen, Denny Gulla, Cecil Ray, Norm Matzke, Robin Clark, Graydon Matheson, Ted Moser, Bill Michaels, J. K. Pewitt, Brent Beden, Malcolm Chang, Barry Anderson, Pat Bowen, Rick Chubb, Paul Griffith, Joe Higgins, Rick Jackson, Gene Kahn, Rob Kellams, Henry McLauchlin, Ross Nooney, Tom Pike, Bob Seager, Mick Stewart, Bob Stockham, Walt Stout, John Tolton, David Walker.

EVIDENCE SPECIALISTS

Tonya Yzaguerre, Cheryl Rivers, Terry McAdam, George Johnston, Chesterine Cwiklik, Jean Johnston, Beverly Himick; Skip Palenik, microscopist, Microtrace; Marc Church; Kirsten Maitland.

OTHER POLICE JURISDICTIONS

Investigators from Washington State: Des Moines Police Department, Tukwila Police Department, Kent Police Department, Thurston County Sheriff’s Department, Snohomish County Sheriff’s Department, Pierce County Sheriff’s Department, Tacoma Police Department, Spokane Police Department.

Oregon: Portland Police Department, Multnomah County Sheriff’s Office, Washington County Sheriff’s Office, Clackamas County Sheriff’s Office.

California: San Diego Sheriff’s Department, San Francisco Sheriff’s Department, San Francisco Police Department, Sacramento Police Department.

Nevada: Las Vegas Police Department.

MEDICAL EXAMINERS

Dr. Donald Reay, Medical Examiner, King County; Bill Haglund, Ph.D., Chief Investigator, King County Medical Examiner’s Office; Dr. Larry Lewman, Oregon State Medical Examiner.

THE PROSECUTORS

Norm Maleng, King County Prosecutor; Marilyn Brenneman, Al Matthews, Jeff Baird, Bryan McDonald, Ian Goodhew, Patricia Eakes, Sean O’Donnell.

THE DEFENSE TEAM

Tony Savage, Mark Prothero, Fred Leatherman, David Roberson, Suzanne Elliott, Todd Gruenhagen, James Robinson.

INTERESTED OBSERVERS

Barbara Kubik-Patten, psychic; Melvyn Foster, unofficial consultant; Cookie Hunt, spokesperson for the Women’s Coalition; Dale Wells, public defender in Spokane.

TASK FORCE CONSULTANTS

Pierce Brooks, former Homicide captain, Los Angeles Police Department, former police chief in Lakewood, Colorado, and Eugene and Springfield, Oregon, serial murder expert; Robert Keppel, Ph.D., serial murder expert; Dr. John Berberich, psychologist; Chuck Wright, Washington State Corrections probation and parole supervisor; Dr. Chris Harris, forensic psychiatrist; Dr. Robert Wheeler, psychologist; Betty Pat Gatliff, forensic artist; Dr. Clyde Snow, forensic anthropologist; Linda Barker, victims’ advocate; Prof. Fio Ugolini, soil scientist; Dee Botkin, phlebotomist.

F.B.I. special agents: John Douglas; Dr. Mary Ellen O’Toole, Behavioral Science Unit; Gerald “Duke” Dietrich, Paul Lindsay, Walt LaMar, Tom Torkilsen, John Gambersky, Ralph Hope, Bob Agnew.

Introduction

AS I BEGAN this most horrifying of all books in my long career as a true-crime writer, I found myself faced with the same dilemma I encountered some twenty-five years ago. In the early 1970s, I worked as a volunteer at the Crisis Clinic in Seattle, Washington. Two nights a week, I worked an all-night shift with a young male psychology student at the University of Washington as my partner. Together we fielded calls from suicidal and distraught people. I hadn’t published a book yet, but by 1975 I had a contract to write one if the nameless killer of at least seven young coeds in Washington and Oregon was ever caught. As many readers know, that murderer turned out to be my partner: Ted Bundy. By the time I learned that, however, he had left the Northwest and continued his murderous rampage in Utah, Idaho, and Colorado. Convicted of attempted kidnapping in Utah, Ted was extradited to Colorado in 1976 to await his murder trials for eight victims in that state, but he escaped from two jails, making his way to Florida after his second—successful—escape on New Year’s Eve, 1977. There he took the lives of three more young women and left another three for dead in Tallahassee and Jacksonville before he was finally arrested, convicted of murder in two trials, and sentenced to death. After nine years of appeals, Ted was electrocuted on January 24, 1989, at Raiford Prison.

How many women did Ted Bundy kill? No one really knows for sure, but when Florida detectives told him that the F.B.I. believed his toll was thirty-six victims, he said, “Add one digit to that, and you’ll have it.” Only he knew if he meant 37, 136, or 360.

Throughout his years of imprisonment, Ted wrote dozens of letters to me, and sometimes made oblique statements that could be construed as partial confessions.

Initially, I tried to write the Ted Bundy saga as if I were only an observer, and no part of the story. It didn’t work because I had been part of the story, so after two hundred pages, I started over on The Stranger Beside Me. There were times when I had to drop in and out of the scenario with memories and connections that seemed relevant. Stranger was my first book; this is my twenty-third. Once again, I have found myself part of the story, more than I would choose to be in some instances. Many of the men and women who investigated these cases are longtime friends. I have taught seminars at law enforcement conferences with some of them and worked beside others on various task forces, although I am no longer a police officer. I have known them as human beings who faced an almost incomprehensible task and somehow stood up to it and, in the end, won. And I have known them when they were relaxed and having a good time at my house or theirs, setting aside for a short while the frustrations, disappointments, and tragedies with which they had to deal.

Was I privy to secret information? Only rarely. I didn’t ask questions that I knew they couldn’t answer. What I did learn I kept to myself until the time came when it could be revealed without negatively impacting the investigation.

So, the twenty-two-year quest to find, arrest, convict, and sentence the man who is, perhaps, the most prolific serial killer in history has been part of my life, too. It all began so close to where I lived and brought up my children. This time, I didn’t know the killer, but he, apparently, knew me, read my books about true homicide cases, and was sometimes so close that I could have reached out and touched him. As it turned out, varying degrees of connection also existed between his victims and people close to me, but I would learn that only in retrospect.

There were moments over the years when I was convinced that this unknown personification of evil had to appear so normal, so bland, that he could have stood behind me in the supermarket checkout line, or eaten dinner in the restaurant booth next to mine.

He did. And he had.

Looking back now, I wonder why I cut a particular article out of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. It wasn’t headline news, and it was so brief that it would have been easy to miss. By the summer of 1982, I had moved on from covering six to eight homicide cases for True Detective and four other fact-detective magazines every month and was concentrating on writing books. I was under contract to do a novel at the time and I wasn’t even looking for true-crime cases to write about. But the short item in the “Local News” section was very sad: Two young boys had found the body of a young woman snagged on pilings under the Peck Bridge on Meeker Street in Kent, Washington. She had floated in the shallows of the Green River, her arms and legs entangled in a rope or some similar bonds.

The paper wasn’t specific about the cause of death, but police in Kent suspected that she had been strangled. Although she had been in the river for several days, no one had come forward to identify her.

The woman was white, estimated to be about twenty-five years old, and at five feet four, she weighed about 140 pounds. She had no identification on her body, and she wore unhemmed jeans, a lace-trimmed blue-and-white-striped blouse, and white leather tennis shoes.

Her clothing wasn’t distinctive, but King County medical examiner Dr. Don Reay noted that she had five tattoos on her body: a vine around a heart on her left arm, two tiny butterflies above her breasts, a cross with a vine around it on her shoulder, a Harley-Davidson motorcycle insignia on her back, and the unfinished outline of a unicorn on her lower abdomen. The delicacy of four of the tattoos warred with the motorcycle-gang mark, but Kent detectives still thought that it might be the likeliest lead they had in finding out who she was—if any members of local motorcycle organizations would admit to knowing her.

I clipped out the coverage of the woman’s death, being careful to save the upper margin of the page with the date. It was published on July 18, 1982. She had actually been found on Thursday, July 15.

The victim hadn’t drowned; she had been dead when she was placed in the river. When a description of her tattoos was published in area papers, a tattoo artist recognized his work and came forward to identify the victim. She wasn’t a grown woman at all; she was much younger. He knew her as Wendy Lee Coffield. “I think she lives in Puyallup with her mother,” he added. “She’s only sixteen.”

Detectives located her mother, Virginia Coffield. Although she appeared to be in shock, the woman murmured, “I kind of expected it.” She explained that she suspected Wendy had been working as a prostitute and might have been attacked and killed by a “john.”

“I know that was the kind of life she chose for herself,” Virginia Coffield said with a sigh. “We taught her the best we could.”

Wendy Lee’s mother said her daughter had been a good little girl when they were living in the country, but that her “trouble” had started when they moved to Auburn and Kent, both of which were still very small towns compared to Seattle and Tacoma.

Wendy and her mother never had much money as Virginia struggled to support the two of them after Virginia and her husband, Herb, divorced; they lived in one low-rent apartment after another. There had even been times in the warm summer months when they had to live in a tent, picking blackberries to sell so they could buy food.

“Wendy dropped out of school—way back in junior high,” her mother said wearily.

She didn’t say, but Wendy had been caught in an all too familiar vicious circle. Virginia herself was only thirty-six, worn and discouraged beyond her years. Her own childhood had been a miserable time where many of the adults who were supposed to be caring for her were more interested in the fuzzy escape of alcohol. She had come from “a big family of drinkers.”

Virginia had become pregnant at sixteen and given that child up for adoption. Then she spent two teenage years at Maple Lane, Washington’s juvenile corrections facility for girls. “I felt like I was a misfit; nobody understood me. She [Wendy] was seeking help just like I did, but they put her out [of juvenile detention] when they should have given her supervision. She just needed a couple of years off the street to grow up.”

By mid-1982, Virginia and Wendy were living in another rundown apartment in downtown Puyallup. Photographs of Wendy showed a smiling girl with a wide, open face. She could have passed for eighteen or nineteen, but she was only a few years past childhood. After she stopped going to junior high, she had been enrolled in Kent Continuation School in the hope that she could catch up. But she was a chronic runaway, perhaps wanting to leave behind a home where she wasn’t happy, or simply looking for excitement out in the world—or both.

Her mother had lost control of her. “Wendy just started having trouble,” Virginia Coffield said, explaining that her daughter was known to police for minor offenses in both King and Pierce Counties. “The last thing she did was she took $140 in food stamps from one of our neighbors.”

One night, when Wendy was fourteen or fifteen, Virginia recalled, she had come home disheveled and upset. “She said some guy raped her while she was hitchhiking. That’s the way she got around. Hitchhiking. I told her that’s what happens.”

Wendy changed after that and her problems grew. Her theft of the food stamps landed her in Remann Hall, the Pierce County juvenile detention center in Tacoma, and then into a foster home. She became a runaway from there on July 8 when she didn’t return from a twenty-four-hour pass to visit her grandfather.

Wendy and her mother had lived a hardscrabble existence, and neither seemed to have met the other’s expectations. Fathers drift away and single mothers despair of ever making enough money to keep going. Rebellious teenage daughters make it more difficult as they act out of their own pain. And so it continues. Wendy Lee got caught in the centrifugal force of it. She wanted the things she didn’t have and she took terrible chances to get them. Somewhere along the way, she had met someone who was angry enough or perverted enough to consider her survival in the world insignificant.

Since Wendy’s body had been found within the Kent city limits, her murder would be investigated by the Kent Police Department. Chief Jay Skewes said that the last time anyone had seen Wendy alive was shortly after she had slipped out of Remann Hall, a week before her corpse was discovered in the Green River. She had been listed as a runaway, but no one had been actively looking for her. There were so many runaways that it was hard to know where to start.

And now Wendy’s sad little life was over before it really began. Her blurry photo appeared over and over in the media as the story of her murder was updated and details added. She was an attractive blond-haired girl, and I had written about hundreds of homicide cases in the dozen years before Wendy was killed, a number of them about pretty blondes who had been strangled.

But she was so young, and I learned she had been violently choked with her own panties. I had teenagers myself, and I remembered the girls I’d known when I was in college and worked summers as a student intern at Hillcrest, the juvenile girls’ training center in Salem, Oregon (a facility once known as a reform school). The Hillcrest residents ranged in age from thirteen to eighteen, and they tried to act tough, although I soon realized just how frightened and vulnerable most of them were.

Maybe that’s why I saved the clipping about the girl in the Green River. Or maybe it was because Wendy’s body had been found close to where I lived in the south end of King County, Washington. At least a thousand times over the forty years I’ve lived here, I’ve passed the very spot where someone threw her away.

To reach this stretch of the Green River from my house, I had to cross Highway 99 and head about four miles down the long curving hill that is the Kent–Des Moines Road. The Green River coursed south from Eliott Bay and the Duwamish Waterway, irrigating the floor of the Kent Valley. In the days before the Boeing Airplane Company expanded and the Southcenter Mall mushroomed, the valley was known for its rich loamy soil and was home to family farms, many of which supplied produce to Seattle’s Public Market, or who simply put up their own stands along the road. When my children were small, I took them every summer to one of the U-Pick strawberry patches that abounded in the valley. We often took Sunday drives through Kent, Auburn, and Puyallup.

I had also driven along Frager Road on the Green River’s western bank in almost total darkness any number of nights, coming home from dinner with friends or from shopping at the Southcenter Mall. The lights of the huge mall faded within minutes as the road became indistinguishable from the river.

North of the Meeker Street Bridge, Frager Road and the rushing river frightened me a little at night because there were hardly any houses nearby, and winter rains made the Green River run so deep that it nudged the shoulders of the road. Drivers under the influence or inexperienced or reckless often missed turns on the narrow road and sailed into the river. Few of them survived. Sometimes they floated in the depths for a long time, because nobody was aware that their cars and bodies waited there beneath the surface.

In the moonless dark, the lonely road along the river seemed somehow sinister, although I could never come up with a good reason why I felt that way. It was just a river in the daytime, running past fields, tumbling-down farmhouses, and one tiny park that had two rickety picnic tables. There were usually a few dozen fishermen huddled in little lean-tos made of scrap wood, angling for steelheads along the river.

Despite my foreboding, I often took Frager Road home after midnight because it was a shortcut to my house on S. 244th Street. When I came to S. 212th, I drove away from the river, turning right and then left up a hill, past the “Earth Works Park,” which was not really a park at all but a huge pile of dirt that had been bulldozed into oblique ascending levels and then thinly planted with grass. The City of Kent had commissioned it as an art project. It wasn’t pretty, it didn’t seem like art and it, too, was faintly threatening as it loomed beside the secluded road that wound up a hill that became steeper and steeper.

I was always relieved when I reached the top and crossed Military Road onto S. 216th. Highway 99—the SeaTac HiWay—where the lights were bright again, was only two blocks ahead and I was almost home.

I rarely had occasion to drive on Frager Road between S. 212th and Meeker Streets, and Wendy’s body had drifted south of where I always turned off. In the summer months when she was found, the water wasn’t deep beneath the Meeker Street Bridge. She would have been in plain sight of anyone who drove across it into Kent. Kent was a small town twenty-two years ago, without the block after block of condos and apartment houses it has now. The place in the river where Wendy’s body floated didn’t abut a golf course or a joggers’ trail two decades ago because they hadn’t been built yet. Kent’s city council hadn’t voted in 1982 to make the city’s entrance picturesque.

Kent was mostly a blue-collar town and Seattle comedians were quick to make jokes about it. Bellevue and Mercer and Bainbridge Islands were the white-collar bastions, but Kent, Auburn, and Tukwila were fair game. Almost Live, the most popular local comedy show, even coined a euphemism for sexual intercourse, calling it “Going to Tukwila” after a local couple claimed the championship for “making love the most times in one year.”

Close to where Wendy’s body was left, there was a restaurant called The Ebb Tide that had moderately good food and served generous drinks in its smoke-filled lounge. A block or so east of that was a topless dancing spot, a two-story motel, and a handful of fast-food franchises.

The Green River was running low in July 1982, and much of the rocky shore with its reedy grasses was exposed. It wouldn’t have been difficult for a man—or men—to carry Wendy from a vehicle down to the river, but it would have had to be done in the hours of darkness. Someone pushing a bike or walking across the bridge, or anyone driving along Frager Road, could have seen what was happening. No one had. At least no one came forward to report any sightings.

The chances were good that the person—or persons—who had murdered Wendy Lee Coffield would never be found. She had quite probably met a deadly stranger who had no ties that might link the two of them with physical or circumstantial evidence. Stranger-to-stranger homicides are traditionally the most difficult to solve.

Even so, I saved the small pile of newspaper articles about Wendy. I drove to the Green River and stood at the spot where she had been found, wondering how she had come to get in a car with the worst person possible. Had it been someone she knew and trusted not to hurt her? Homicide detectives always look first at a victim’s friends, co-workers, and family. If Wendy Coffield had known her killer, the Kent police had a reasonable chance of finding him. If she had encountered a stranger with violence in mind, her case might very well end up in the unsolved files.

ALONG WITH THE NEWSPAPER clippings I saved, I began to receive letters from women with terrifying memories to share.

I don’t remember what month it was, or even what season. I do remember that it was in 1982 or 1983. I was nineteen, maybe even twenty at the time. It’s hard for me now to be sure because it’s been a really long time ago. I was “working,” because I didn’t have much choice—I had a big hassle with my mother and I didn’t have a place to live or a way to eat except to be on the streets. In those days, I pretty much worked in downtown Seattle and my street name was “Kim Carnes”—I got that from the song about “Betty [sic] Davis Eyes”—because, you know, none of us liked to use our real names. We knew we’d be out of “the life” pretty soon and we didn’t want any connection to…you know…

This particular john picked me up at the Greyhound bus depot on Eighth and Stewart. He was driving kind of a clunker of a car. I’m pretty good on details ’cause it was safer I figured to pay attention. It was a light blue Ford sedan with four doors, and it had vinyl seats. He told me that he was taking me to a party, and I believed him and said that was okay, but I knew that it was a “date” for money.

He got on the I-5 Freeway right there close to the Greyhound station and headed south, but it seemed like we were going a long, long way. I mean, I knew the south end of the county pretty good because I’d had this job where I delivered parts to Boeing at the plant out in the Kent Valley. I was starting to get a little bit suspicious. I kept asking him where we were going, and he seemed like he was getting nervous. He just said we’d be there “Soon—soon.”

I was trying to make conversation, but he was getting really antsy. One time he pointed kind of over toward the east and he told me that he worked over there “across the river.” That would have been the Green River and I thought he meant he worked in Kent.

I kept asking him how far the party was and he started to get angry and he was rude to me. But then he turned off on the Orilla Road South exit that’s just past Angle Lake and it goes down to the county dump there, and on down the hill into the valley. I thought that was where we were going, but then he made a turn and we were going up a hill, and through some streets where there were a lot of houses. I figured that’s where the party was supposed to be, but he didn’t stop—not until we came to this field or maybe it was just a big vacant lot. It was really lonesome out there with trees all around it. You couldn’t see any lights, only the moon.

I was really scared by this time because we were so far from the freeway and we weren’t near any houses, either. On the way out, I’d been memorizing everything I could about his car and I’d noticed that the glove box didn’t have a lock on it—only a button. He reached over me and popped it open and I saw that there was a stack of Polaroid pictures in there. He made me look at them. The first one was of a woman with red lingerie wrapped all around her neck and her face seemed kind of swollen. She looked scared. The thing I remember about all the pictures was that the girls in them had the same look in their eyes, like they were trapped. I didn’t ask him who they were because I was too afraid.

By this time, I knew I had to think really fast and not let him know I was scared, so I pretended that we were just out there to have sex and didn’t give him any fight because it wouldn’t have done any good, anyway. I asked him what his name was, and he said it was Bob, but didn’t give me his last name. He reached in the back seat and pulled out a brown paper bag—like a grocery bag. I could see it was stuffed with all kinds of women’s underwear, like you can buy at Victoria’s Secret. He held up the bras and panties and stuff and lots of the things were torn or dirty. He wanted me to put some of it on and I said I couldn’t do that.

I don’t know where he got it from, but he was holding a gun. It was a “short” gun, like I guess you call a hand-gun. He held it up against my head behind my ear. He made me give him a blow-job. I didn’t want to because he had these weird bumps or something all over his penis, but he kept the gun to my head all the time I was trying to get him off. It seems like it was forty-five minutes that I kept trying, but I kept gagging because of the bumps. That made him real angry.

I was sure he was going to shoot me. He never lost his erection and he didn’t ejaculate. Finally, I just started talking as fast as I could and somehow I convinced him to take me back to Seattle. I told him I had this friend who was really lonely and that she had been looking for a guy just like him and she would be a perfect date for him and he wouldn’t have to pay her or anything. I gave him her phone number, but it wasn’t really her number—I just made it up.

All the way into town, I kept talking and talking, because I was afraid he was going to pull off someplace and try again, but he took me back to the bus station. I didn’t call the police because I didn’t trust them. One time I got arrested for prostitution and this one cop opened up my shirt and just looked down at my breasts, and there was no reason for him to do that. So when this happened to me, I decided I wasn’t going to tell them anything. I wasn’t hurt and I wasn’t dead.

The nightmares didn’t go away, though, for a long time. See, when I was younger, my stepfather fooled around with me and then he raped me. I told my mother but she wouldn’t believe me. I found out then that nobody believes you when you tell the truth. Especially the cops. I just kept it to myself for all these years. I’m in a straight life now and I have been for a long time. I’ve got a good husband, and I told him what happened. When I saw this guy’s picture in the paper, I recognized him. I knew that I had to tell somebody.

What did he look like? Pretty average. Not too tall. Not too heavy. Just a guy. But I still feel that I came this close to getting killed, and the funny thing is that when I got into his car, I had him pegged as harmless…. I never would have believed that he could murder all those girls.