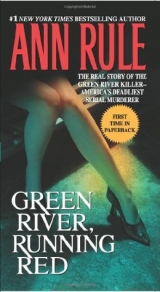

Текст книги "Green River, Running Red. The Real Story of the Green River Killer - America's Deadliest Serial Murderer"

Автор книги: Ann Rule

Жанр:

Маньяки

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 37 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

Afterword

THE GREEN RIVER TASK FORCE, much diminished, continues to follow up unsolved crimes and unidentified bodies that may be linked to Gary Ridgway. The consensus is that there will be more corpses surfacing in the months and years to come. In the meantime, the world moves on without him.

Dave Reichert is still the sheriff of King County, but perhaps not for long. Ridgway’s capture made Reichert a media star. For two years, rumor had it that Reichert would run for governor. Instead, he set his sights on Washington, D.C., and, in 2004, became a Republican candidate for Congress representing the Eastside of King County. If he should go to Washington, it is likely that Tom Jensen and John Urquhart will go with him.

Sue Peters went to Africa on safari in early 2004, about as far as she could get from the cloistered interview room at Green River headquarters where she spent six months in 2003. She continues to work on the Green River cases, hoping, especially, to find an answer to Keli McGinness’s fate.

Some years ago, Peters and Detective Denny Gulla, determined to save as many young women as they could, put together a program called the Highway Intelligence Team (H.I.T.). With detectives Jesse Anderson and Christine Bartlette, they go back once a month, to the Strip and other locations where prostitution is rife, looking for the working girls of a new generation. They are not there to arrest them but rather to check on their welfare.

“I give them my card,” Peters says, “and tell them they can call me twenty-four hours a day if they need help. I do my best to put them in touch with services they need and, hopefully, to get them off the street.”

Peters and the other three detectives are available all the time, and she has received phone calls from desperate girls at all hours of the day and night. “When I get to know them, I ask for the names of the motels where they usually stay, for their dental information, and if they have any significant scars,” Peters says. “Sometimes they ask me why I need to know that, and I tell them the truth: ‘So we can identify your body if something happens to you.’ That shocks them and makes them realize how dangerous it is to be out there.”

A few of Peters’s and Gulla’s “regulars” call once or twice a week just to check in. It gives them a lifeline and a connection to someone who cares about them. Although gathering information is definitely not the primary purpose of H.I.T., many of the young women report “bad dates” and their license plate numbers. Some of their warnings have led to the arrests of serial rapists.

Randy Mullinax has put together a comprehensive seminar on the Green River investigation that is much in demand with law enforcement agencies all over the country.

Bob Gebo, Ed Streidinger, and Kevin O’Keefe have returned to the Seattle Police Department. Frank Adamson has retired. Richard Kraske has retired. Cherisse Luxa has retired. Ben Colwell has retired. Medical Examiner Dr. Donald Reay has retired, and lives on an island in Puget Sound where he recently completed a class on repairing boat motors—as far from forensic pathology as he could get.

Bill Haglund continues to aid in identifying victims of terrorist slaughters in foreign countries.

Danny Nolan, Paul Smith, Ralf McAllister, Jim Pompey, Dr. John Berberich, and Tonya Yzaguerre are deceased.

Matt Haney is the chief of police of Bainbridge Island, Washington. Robert Keppel is a professor at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas, teaching criminology and investigative techniques.

Judith Ridgway lives in seclusion, but has told friends that she plans to write a book about her marriage to Gary Ridgway.

Chad Ridgway is in the marines in California.

Judy DeLeone, Carrie Rois’s mother, broke her ankle a few years after Carrie’s remains were found. An undiagnosed blood clot formed, and she died suddenly from a pulmonary embolism.

Mertie Winston suffered a stroke shortly after Tracy Winston’s remains were identified, but has fought her way back to complete recovery.

Suzanne Villamin lives with her little dog in an apartment in downtown Seattle, surrounded by memories of her daughter, Mary Bello.

Looking through a two-foot-high stack of emails, letters, and phone notes I received over twenty-two years, I was once more amazed at the diversity of Green River Killer suspects: doctors, lawyers, psychologists, cops, pilots, writers, blue-collar workers, students, cultists, salesmen, cabdrivers, bus drivers, parolees, ministers, teachers, politicians, actors, and businessmen. In the end, it came down to the realization that the Green River Killer could have been almost anybody.

Almost anybody but a boring little man of seemingly predictable habits, a penny-pincher, miser, a collector of junk, and a target for jokes and demeaning nicknames. And yet it was Gary Ridgway’s protective coloration that let him stay free for more than twenty years. That and his uncommon ability to mask what lay beneath his bland facade and to hide his rage and frustration from his ex-wives, numerous girlfriends, his family, and even the woman who became his third wife. Judith Ridgway appeared to have truly believed that she and Gary “did everything together.” She was confident that neither of them had a need for friends or other diversions.

Gary Ridgway was good at only one thing. He was an efficient killer who was so inept at everything else that it was easy for him to hide in plain sight. In a way, he achieved what he had sought for most of his life. At last, people noticed him and he got his name and picture in the paper and on television.

For six months, he spent his time with detectives who, although they were much smarter than he, were obliged to come to him for answers. He got to go on field trips, and if their body site searches continued over a mealtime, he got to order fishwiches or hamburgers and french fries at fast-food drive-throughs.

In January 2004, when Ridgway was transferred, secretly of course, to the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla, he fully expected that he would continue to be a celebrity. He was taken first to the M.H.U.—the Mental Health Unit—where he would stay until May undergoing various tests.

“He had a cocky attitude,” an observer said. “You could tell that he thought he was superior to the other prisoners—that he was special.”

He soon learned that he was not. The stream of detectives he had expected to visit him did not appear, although he was flown once to Snohomish County, just north of King County, to go on field trips there. Nothing significant was found. The media was unaware of the quick trip.

Ridgway is considered prey in the Walla Walla prison for several reasons: most prisoners despise him for his crimes against women—rapists and child abusers are on the very bottom rung in the penitentiary; some convicts are related to the victims or their friends and would jump at the chance to wreak vengeance. Perhaps most of all, the prison hierarchy would reward any man who killed Ridgway. It would be a real feather in the cap of the con who managed to accomplish such a difficult feat. Wisconsin serial murderer Jeffrey Dahmer didn’t survive long in prison; he was murdered in the shower room. In 2003, a Catholic priest convicted of child abuse was strangled shortly after he entered the General Population.

During Ridgway’s first few months in the M.H.U. in Walla Walla, one prisoner managed to get very close to him before he was spotted, quickly restrained, and hustled away. Ridgway will, indeed, have to keep his back to the wall—even when he is in solitary.

In May 2004, Ridgway was transferred to the I.M.U.—the Intensive Management Unit—where the most dangerous and difficult prisoners are housed in single, boxlike cells, shut off from the General Population of the prison. There, he is confined to his cell twenty-three hours a day. His accommodations are spartan, and it is rare to see a woman in the I.M.U. He is housed with the worst of the worst: women killers, sexual perverts, convicts whose crimes once made sensational headlines but who have long since been forgotten—shut off from the world with no hope of parole.

One of the other inmates on his tier laughed as he told a visitor about Gary Ridgway’s first night in the I.M.U. He had activated the emergency signal. When a guard responded, Ridgway complained loudly that there was a “hole in my blanket.”

“Then put your toe in it,” the guard responded. “And never ring that alarm again unless you have a real emergency.”

Just before Ridgway was sentenced to forty-eight life terms, he said that his worst fear was that he had forgotten some of his victims and the places where he left them. There is every likelihood that he has not yet revealed everything he has done. He knows full well that his plea bargain will be voided if it can be proved that he purposely held back information. And he has no plea bargains with other jurisdictions; he has admitted to leaving bodies or parts of bodies in Oregon, but insists that he committed all his murders in King County, Washington.

The geographical location of murders still undiscovered may yet see Gary Ridgway die in the death chamber.

Acknowledgments

OVER the past twenty-two years, scores of people have helped me with various aspects of my research, writing, and preparing this book to go to the printer. I am so afraid I will forget someone, but I’m going to try to go back to July 1982 and thank everyone who played a part. In some instances, I will use an alias or only a first name. The reasons, I think, will be obvious, and I know readers will understand.

It hasn’t been easy for grieving families to answer some of the questions I asked them, and I am forever grateful that they were willing to talk to me about the good days and the sad days of their lives.

Bill Aadland, Frank Adamson, Mike Barber, Linda Barker, David Bear, Brook Beiloh, Moira Bell,* Bren and Sharon, Marilyn Brenneman, Darla Bryse,* Lorrie C.,* Lynne Dickson, Gerald “Duke” Dietrich, Val Epperson, Families and Friends of Violent Crime Victims, Gene Fredericksen, Betty Pat Gatliff, Bill Haglund, Matt Haney, Ed Hanson, Jon Hendrickson, Maryann Hepburn,* Edward Iwata, Robert Keppel, Jean Knollmeyer, Dick Kraske, Katie Larson, Pat Lindsay, Lorna, Cherisse Luxa, Rebecca Mack, Norm Maleng, Josh Marquis, Al Matthews, Bruce McCrory, Dennis Meehan, Garrett Mills, Randy Mullinax, Kevin O’Keefe, Princess Oahu, John O’Leary, Sue Peters, Charlie Petersen, Barbara Potter, Don Reay, Barbara and John Reeder, Dave Reichert, Robert Ressler, Elizabeth Rhodes, Cheryl Rivers, Ruby, Mike Rule, Austin Seth, Paul Sherfry, Norm Stamper, Anne Stepp, Tenya, Kay Thomas, Kevin Wagner, Don White, Don Winslow, Mertie Winston, Chuck Wright, Suzanne Villamin, and Luanna Yellow Robe.

I APPRECIATE my friends who have forgiven me for staying glued to my computer these past six months: my always dependable first reader Gerry Brittingham Hay; my organizer Kevin Wagner; Betty May Settecase and the rest of the “Jolly Matrons,” a secret—but friendly—society who have known each other since we were seventeen, Joan Kelly, Sue Morrison, Sue Dreyer, Patricia Potts, Shirley Coffin, Gail Bronson, Alice Govig, Shirley Jacobs, Joyce Schmaltz, and Val Szukovathy. To my fellow writers Donna Anders and Leslie Rule, and all my old pals with whom I’m going to go out to lunch again: Shirley Hickman and Rosalie Foster, Claudia House, Chirlee House, Margie McLaughlin, Cece Coy, Jennifer Heimstra, Marnie Campbell, Bonnie Allen, Elisabeth Fredericksen, Janet West, Patty Greeney, Gretchen DeMulling, Dee Grim, and Maureen Woodcock.

I am very lucky indeed that I still have my editorial and publishing team at Free Press/Simon & Schuster/Pocket Books as we work on our seventeenth book together. Authors need editing and more editing, a clear legal head to advise them, production people, proofreaders, designers in the art department, an enthusiastic marketing department, creative publicists, and accurate printers. This is my writing home, and I am glad I found it! Thank you all for so many years of support and friendship: Carolyn Reidy and Martha Levin (publishers); Fred Hills and Burton Beals (editors); Kirsa Rein (editorial assistant); Isolde Sauer, Jane Herman, Betty Harris, and Eva Young (copyediting); Jennifer Weidman (legal); Carisa Hayes and Liz Keenan (publicists); Karolina Harris (text design); Hilda Koparanian (production); and Eric Fuentecilla (cover design).

I chose the best literary agents in the world—at least for me—thirty-five years ago, and Joan and Joe Foley are, happily, still with me. Thanks to Ron Bernstein of International Creative Management for representing my theatrical rights.

There is also an irreplaceable team in Seattle who never let me down as the deadlines creep up: Roadrunner Print and Copy, Entre Computer, and the FedEx folks at the SeaTac Airport who hold the door open as I come racing up with finished manuscript pages due in New York City overnight.

And, finally, to my “writing dogs”—Lucy and Willow—and the cats who sit on my warm computer—Fluffbutt, Beanie, Bunnie, and Toonces. They all keep me from getting lonesome when days go by without my seeing human beings.

About the Author

ANN RULE is the author of twenty-one New York Times national bestsellers, all of them still in print. A former Seattle police officer, she has a B.A. in Creative Writing from the University of Washington, an A.A. in Criminal Justice from Highline Community College, and a Ph.D. in Humane Letters from Willamette University. She is a certified instructor for police, probation, and corrections officers, and for CLE and CME, and has taught seminars to many law enforcement groups, including the F.B.I. Academy, for many years. She has been an active advocate for victims’ rights organizations for three decades. She has testified before U.S. Senate judiciary subcommittees twice, and was one of the five civilian advisers on the VICAP (Violent Criminal Apprehension Program) Task Force to set up its program to track and trap serial killers. Ann is currently at work on two new books. She lives near Seattle, and can be contacted through her website pages at www.AnnRules.com.

Ann Rule, standing beneath the Peck Bridge on the edge of the Green River in Kent, Washington, at the exact spot where Wendy Lee Coffield’s body was found in July 1982. No one could imagine then that Wendy was only the first of more than fifty victims.

Debra Lynn Bonner, 22, was found in the Green River a month after Wendy Lee Coffield. Although she rarely had a permanent address, Debra was deeply loyal to her family and always carried their photos and mementos.

A King County police diver holds Debra Lynn Bonner’s dress, found in the Green River near her body in August 1982.

An aerial photograph of the Green River as it winds through a fertile valley in southeast King County, Washington. After the summer of 1982, the name Green River triggered thoughts of deadly violence instead of serenity. The bodies of five young women floated there, hidden by the tall grass.

The Robert Mills family, 1972 (REAR: Robert and Kathy; FRONT: Garrett and Opal). Opal and Garrett suffered from racial prejudice in school and stuck together fiercely. Garrett always felt responsible for his little sister’s safety and his ultimate failure to protect her haunts him still.

Because Garrett Mills had survived delicate heart surgery at age five, he and Opal collected money to give to the Childrens’ Orthopedic Hospital. Opal, whom her brother called “The Little Peanut,” was still safe then.

One of the last photographs of Opal Charmaine Mills, at 14 or 15, 1981. As a teenager, Opal lived a rich fantasy life, fancying herself in love with boys and men she hardly knew. Gullible and vulnerable, she, too, was left at the Green River.

A brown truck with a camper shell didn’t stand out as suspicious on the Pac HiWay “Strip” in the early eighties. Later, witnesses would remember this pickup, along with similar vehicles that patrolled the highway.

The Strip where prostitution proliferated from 1982 to 1985, the busy Pac HiWay that runs past Seattle’s SeaTac Airport. It became the prime hunting ground for a serial killer who targeted teenage girls.

Sheriff’s Lt. Dick Kraske confers with his detectives at the North Bend body-cluster site where several Green River Killer victims were found.

Lt. Dick Kraske after his retirement. He was at the center of both the “Ted” (Bundy) murders in the midseventies and the Green River probe seven years later.

In 1983, the first Green River Task Force posed for a photograph in the cramped office between floors in the King County Courthouse. FROM LEFT: Elizabeth Druin, Pat Ferguson, Sgt. Bob “Grizzly” Andrews, Ben Colwell, Dave Reichert. SEATED IN FRONT: Lt. Dan Nolan. Despite questioning hundreds of people about the murders, there were no easy answers.

Giselle Lovvorn, 17, traveled America following The Grateful Dead, but the freckled blond teenager with a genius I.Q. had decided to go home to her California family when she vanished from the Strip in July 1982. Her body was found in late September, the first victim of the GRK to be left away from the river.

Melvyn Foster, a taxi driver, knew the Strip and its habitués well. When he came forward to offer his advice to the task force, he instead became a “person of interest” as he revealed startling knowledge of the young prostitutes along the highway.

Detective Dave Reichert (LEFT) and Detective Mick Stewart during an extensive search of Melvyn Foster’s father’s home near Olympia, Washington, in September 1982.

Mary Bridget Meehan, 18, was a bright Irish adventuress, much loved by her family. She was a rebel who longed for a safe harbor, babies, and music, but she wandered too far to come home again.

Mary Bridget and her longtime boyfriend Ray. She was 8½ months pregnant with Ray’s baby when she disappeared from the Strip on September 15, 1982.

Detectives and medical examiners remove the remains of Mary Bridget Meehan and her unborn child from a shallow grave only a few blocks off the Strip in November 1983. She was one of the few victims who had been buried rather than just dumped.

Constance Elizabeth “Connie” Naon lived in her car, worked at a minimum-wage job, and occasionally on the streets, trying to make it on her own.

Green River Task Force detectives look for physical evidence at the site where Connie Naon’s, Mary Bridget Meehan’s, and Kelly Marie Ware’s bodies were found near SeaTac Airport.

Shawnda Leea Summers at the beach in a happier time. Missing for a long time, her remains were finally identified as those found in an apple orchard south of the SeaTac Airport, not far from those of Giselle Lovvorn’s.

Frank Adamson led the Green River Task Force longer than any other command officer. He had high hopes of closing the cases, but after seven years the killer was still elusive.

Sandra Kay “Sand-e” Gabbert, 17, was a free spirit full of life. She told her mother that she could make more in one night on the Strip than she could in two weeks at a fast-food restaurant. In the spring of 1983, Sand-e promised her, “I’ll be careful,” and walked away into the night…forever.

Carrie Ann Rois, 16, wanted to be a model and actress but she met the wrong man. Once, he let her go, and she trusted him. In the spring of 1983, he didn’t.

Carrie, age five, opens her Christmas presents. Her happy childhood days evaporated as she entered her teens and became a truant and runaway.

Carrie Ann Rois ended up in a dank ravine at this Star Lake body-cluster site. A dirt biker thought her skull was a football before realizing what it really was. Six victims were found here, and Carrie was the last to be discovered.

1985. Ann Rule stands at the Star Lake Road site next to a tree still emblazoned with a bright red “1” to mark where the first body was found. It was Gail Lynn Mathews, whose boyfriend had seen her last riding with a stranger in a pickup truck on the Pac HiWay.

Kimi-Kai Pitsor, 16, vanished within a day of Sand-e Gabbert, but her remains were found far away in a different cluster—at Auburn’s Mountain View Cemetery. This stolen Lincoln Town Car, pushed over a ravine, was unconnected to the four murder victims, but led searchers to the remains found nearby. Kimi-Kai was the only one identified.

Four witness drawings—individuals’ memories varied greatly. Were any of them the Green River Killer?

Randy Mullinax spent many years on the Green River Task Force. A young detective here, he would become both a shrewd investigator and a tremendous comfort to grieving families.

Mary Sue Bello, 25, tried to help the Green River Task Force stop the roving killer when she reported a suspicious John.

While Mary Sue Bello had her wild side, she was also a loving daughter and granddaughter who was turning her life around when she disappeared. This is her mother’s favorite picture of her.

The small house on 32nd Street South looked much like others. Friends, neighbors, and the owner’s girlfriends who were invited inside had no idea what horrors took place here.

The Green River Killer’s fortunes rose steadily as he moved to a better house and neighborhood during the two decades he eluded detectives.

The Green River Killer took his un-suspecting prey to his master bedroom in his first house to have sex, knowing what would happen afterward. Ironically, he chose a wall mural that resembled the lonely woods where he planned to leave their bodies.

Ann Rule helped Forensic Artist Betty Pat Gatliff rebuild a face on the skull of an unknown Green River victim found at the Star Lake cluster. It took X-rays of Gail Lynn Mathews’s broken bones from a boating accident to confirm her identity.

Matt Haney joined the Green River Task Force in the mideighties, and partnered first with Randy Mullinax. Haney honed in on one suspect, but it would take almost fifteen years to prove he was right.

Delise Louise “Missy” Plager in one of her rare happy moments. A twin, she had to be resuscitated at birth and survived despite great odds. The space between her front teeth helped to identify her skeletonized remains.

Randy Mullinax (LEFT) and Fae Brooks (RIGHT) dig and sift dirt near where Missy Plager’s remains were found in the forest near Highway 18 and I-90.

Tracy, age 7, grew up in a happy suburban family. She was only ten years past her childhood days when she vanished in September 1983.

Tracy Ann Winston trusted everyone and tried to help them. Sadly, her perception of evil was flawed, and she mistook a killer for a friend.

Tracy always loved baseball and, due to her powerful throwing arm, was one of the first girls ever allowed to play on a boys’ Little League team. Here she hugs her mom, Mertie Winston, with whom she had a special bond.

In March 1986, Green River Task Force members and Explorer Search and Rescue Scouts prepare to search Cottonwood Park on the bank of the Green River. Lt. Jackson Beard, fourth from left in green jumpsuit, directed this search as he had many others. It would be thirteen years before they identified the remains as Tracy Winston.

William J. Stevens II, a Gonzaga University law student, led a secret life for many years. His collections of police paraphernalia and pornography and his hatred of prostitutes triggered the Green River Task Force’s suspicion. Entering a King County courtroom in 1989, he was now the prime suspect.

Gary Ridgway, who grew up near the Strip, was a familiar commuter as he drove the highway to the job he held for more than thirty years. Here he poses with his second wife, Dana,* with whom he had a son, but they divorced in 1981.

Gary’s first two wives had issues with his mother, Mary, who continued to dominate her grown son’s life.

The newly single Gary Ridgway was arrested in 1982 for soliciting a prostitute, a minor charge.

Sue Peters and Randy Mullinax, Green River Task Force veterans, stand next to evidence folders. Along with Tom Jensen and Jon Mattsen, Peters and Mullinax were the detectives who questioned the prime suspect almost daily throughout the summer of 2003.

One prime suspect, a truck painter at Kenworth Trucks, denied that he had any connection to the victims. Even so, Green River Task Force detectives searched the rafters in the Kenworth plant for possible mementos—photos or jewelry—taken from the dead young women.

During their many years together, Gary Ridgway and his third wife, Judith, had gone from a camper “with a coffee can for a bathroom” to a sumptuous motorhome.

Judith laughingly called Gary and herself “pack rats,” because they spent their weekends at garage sales, swap meets, and even dumps.

Gary Ridgway, 52, under surveillance, looks around nervously as he approaches his pickup truck on November 30, 2001.

Gary Ridgway after his arrest on November 30, 2001. He was stunned to find Detectives Jim Doyon and Randy Mullinax waiting for him when he left work on that stormy Friday.

When Ridgway was arrested, he wore jeans and a plaid shirt, the clothes described by abduction witnesses—but also the clothes worn by half the men in south King County.

Gary Ridgway wears coveralls after task force detectives bagged and labeled all his clothing, so it could be searched for trace evidence on November 30, 2001.

Dave Reichert, now the sheriff of King County, called a news conference with Prosecutor Norm Maleng on November 30, 2001, to announce the arrest of Gary Ridgway. Now a grandfather, Reichert was a detective for only a few months in August 1982, when he was assigned as lead detective in the murders of Debra Lynn Bonner, Cynthia Jean Hinds, Marcia Faye Chapman, and Opal Charmaine Mills.

King County Task Force investigators in the backyard of the Ridgways’ property in early December 2001. With a suspect in custody, they finally had good reason to smile. LEFT TO RIGHT: John Urquhart, Tom Jensen, and Steve Davis.

Task force investigators dug up the yard behind the house in Auburn, looking for the remains of victims still missing. After excavating the land around three of Ridgway’s houses, they replaced the dirt and plants, having found nothing at all.

Washington State Patrol crime scene investigators processed the interior of Judith and Gary Ridgway’s present and former houses. They wore booties and latex gloves to avoid cross-contamination with evidence, but found nothing of evidentiary value.

Patricia “Trish” Yellow Robe, a beautiful member of the Chippewa Cree tribe, was found dead in 1999. An autopsy found her death to be accidental—the result of an overdose—but, shockingly, the killer admitted to her murder. He had not stopped killing in 1985 as he previously claimed.

There are dozens of young women still missing in Washington and Oregon, including Keli Kay McGinness, who disappeared in the spring of 1983. Detective Sue Peters is still actively seeking Keli. The Green River Task Force continues and probably will for many years.