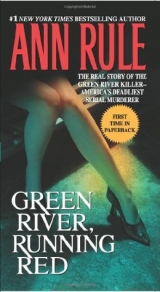

Текст книги "Green River, Running Red. The Real Story of the Green River Killer - America's Deadliest Serial Murderer"

Автор книги: Ann Rule

Жанр:

Маньяки

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 33 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

Except when they were in deep woods, Ridgway was never allowed to get out of the police units; that might have allowed someone to recognize him. But he was there, an interested spectator as well as a guide who led detectives back to where he’d left the bodies of his victims more than twenty years earlier. In order to learn what they needed to know, detectives had to allow him to revisit these sites that he had returned to often over the years of his freedom. He brightened, smiling in anticipation, as they got closer to his trophy areas.

And no one outside the investigation ever suspected.

Ridgway was guarded on every side and hampered by handcuffs with chains attached to a chain on his waist, along with leg irons. There was no chance he could escape. He rode in a locked police vehicle with two detectives accompanying him and two more in a car following. Prosecutors and his own attorneys were also in the search parties.

“He never knew when we were going,” Sue Peters recalled. “We might wake him up before the sun rose, or take him in the middle of an interview. He had no forewarning. He liked the field trips, but we couldn’t help that. Whatever he was reliving, it was something we had to know.”

For the most part, the interviews themselves were handled by four Green River detectives: Randy Mullinax, Sue Peters, Tom Jensen, and Jon Mattsen. Occasionally, psychiatrists spent hours with Ridgway, and Dr. Mary Ellen O’Toole from the F.B.I.’s Behavioral Science Unit flew in to talk with him in her soft, feminine voice, her eyes unblinking as he spoke of his perverted fantasies. “We were relieved when the F.B.I. or the doctors talked to him,” Peters remarked. “It gave us some time away from him.”

That was understandable. A long time later, it was hard enough for me to watch the interviews, caught on DVDs, without having to have been there, masking the revulsion that came with his unfeeling recitation of his crimes. The questioning was usually accomplished in an hour-and-a-half to two-hour segments.

A team of two detectives sat at a round, Formica-topped table across from Ridgway, who was manacled even inside the task force headquarters, although he could move his hands enough to take notes or drink from his bottle of artesian water. He wore jail “scrubs,” usually bright red, sometimes white. At a rectangular table, just out of camera view, members of Ridgway’s defense team listened and watched. A wrinkled gray painter’s tarp covered the wall behind the prisoner, although other detectives could observe and hear what was going on through the closed-circuit television system.

“We quickly learned how to deal with him,” Peters recalled. “He would have enjoyed talking for sixteen to eighteen hours a day, but none of us wanted to listen that long. At first he seemed to think he was running the show. When we gave him a choice of what he wanted for breakfast or lunch, he got the wrong idea and thought he was in some kind of control, so after that he ate whatever we decided he should get.”

If he was particularly forthcoming, Ridgway realized small rewards—a salmon dinner, or extra pancakes, something he wanted to read—although his dyslexia made that difficult for him.

They established a routine. Most of their morning interview sessions began shortly after eight with a recitation of what the prisoner had eaten for breakfast: “Pancakes, an egg, sausage,” Ridgway would say with a smile. And then he evaluated the quality of his sleep during the night while the detectives feigned interest. He appeared to be sleeping remarkably well, given the ghastly imprints laid down in his memory. But since this was all about him, the memories of the dead didn’t disturb him.

They never had.

WATCHING the videotapes that caught every word of the interrogations of Gary Ridgway during those four months of 2003 would have been an unsettling experience for anyone, hundreds of hours of grotesque recollections from a man who looked totally harmless as he described killing dozens of women in a halting, dispassionate voice. Like all criminals, he minimalized his crimes initially, only slowly admitting the monstrous details. While he had ample motivation for telling the truth—his life—he said he knew he was a pathological liar.

“Ridgway also suggested another reason why he would lie or minimalize his conduct,” Jeff Baird, the chief trial deputy, wrote in the prosecutor’s summary of evidence. “He believes that a popular ‘true crime’ author will write a book about him, and he wanted to portray himself in the best possible light.”

In the beginning, Ridgway denied any premeditation to murder, claiming that he killed when he was in a rage. It was the victims’ fault because they didn’t seem to be enjoying sex with him or they made him hurry. “When I get mad, I shake. Sometimes I forget to breathe and things get all blurry,” he said.

Of course, the anger wasn’t his fault either; he blamed his failure to be promoted at Kenworth on women, who got the best and easiest jobs. His first two divorces were his ex-wives’ fault, as were the child support payments he’d had to make for Chad even though he hadn’t wanted a divorce in the first place. Small things enraged him; when he bought his house, the sellers were so cheap they had taken all the lightbulbs. All these things made it difficult for him to sleep, and he said the only way to release the “pressure” had been to kill women.

That wasn’t true, and his specious reasoning soon faltered. He had wanted to kill for the sake of killing, although even he may not have known why. Again and again, he would repeat, “All I wanted to do was have sex with them and kill them.”

It was obvious early on that Ridgway could remember neither his victims’ faces nor their names. His memory wasn’t all fuzzy, but it was compartmentalized. He recalled every vehicle he’d ever owned, houses he’d lived in when he was a child, his various shifts at Kenworth—basically inanimate objects. (Ted Bundy had been like that, too. He could cry over a dented Volkswagen or an abandoned bicycle, but not a human being.)

Gary Ridgway had maps in his head and sharp recall of where he had left bodies, but the dead girls were apparently interchangeable in his mind. Who they were or what they might have become made no difference to him. They had existed only to please him sexually for a short time and they were then disposable.

Some he had deliberately let go, saying, “You’re too cute for a guy like me.” But that, he explained, was only so he would have witnesses, if he should ever need them, that he was a good guy.

“A couple of times the urge to kill wasn’t there. It could have been where I had a real good day at work. Somebody patted me on the back, ‘You did a good job today,’ which was a rarity. It could have been maybe on my birthday…or maybe I just didn’t have time to kill them and take them someplace.”

The detectives worked out ways to stimulate Ridgway’s memory. They did their best to keep him on track, and to recall one victim at a time. When his train of thought began to wander away, they brought him back. Sue Peters often showed him photographs of the living girls, and he shook his head. They didn’t look familiar to him. He had never really bothered to look at them in the first place. He recognized photos of locations, however, saying that fences, trees, or road signs helped him pinpoint them.

The investigators used innovative ways to reach the stuttering, expressionless prisoner. He seemed cowed by the strength of the male questioners, perhaps more responsive to the female interrogators, but there wasn’t a vast difference in his response from one to the other. He may have felt powerful with his victims, but they were such pathetically easy targets. He seemed a mouse now.

“Think of it as a paint job,” Tom Jensen said, as he attempted to trigger Ridgway’s recollection of his crimes. “What do you do first?”

“Well, you prep it. Do the taping and all.”

“So, how did you prep taking the women?”

“I asked if they were ‘dating,’ and told them what I wanted and I waved money at them, and we decided that.” He said he offered them more than they usually got, but that didn’t matter because he knew he wouldn’t have to pay them anyway.

Some of the victims were killed out of doors on the ground after he had spread a blanket he carried in his truck. Some died in the back of his truck. During the times when he lived alone in the little gray house off Military Road, his preference had been to take the women, whom he ironically referred to as “ladies,” to his house. He set their minds at ease in different ways. “A lot of them asked me if I was the Green River Killer when I picked them up,” Ridgway said. “I told them ‘No, of course not. Do I look like the Green River Killer?’ And they says, ‘No, you don’t.’ They always thought it was a big tall guy—about six three, 185 pounds.”

There were women who refused to “date” Ridgway because they were afraid he was an undercover cop. He alleviated their concerns by keeping beer in his truck and offering it to them, and they relaxed because a police officer wouldn’t do that.

He had most of his bases covered. To allay the fears of the frightened girls, he kept some of Chad’s toys on his dashboard. He wanted to appear as an ordinary Joe, a good guy who was a single father. He kept cartons of cigarettes to give away. Sometimes he groomed girls by dating them a few times, offering to help them get jobs, to become a regular customer they could count on, or let them use his car. “And they think, you know, ‘This guy cares,’ and…which…I didn’t. I just wanted to get her in the vehicle and eventually kill her.”

Even when he had the girls in his house, he showed them his son’s bedroom with its toys and souvenirs, keeping up his pretense of normalcy. Once in his house near the Pac HiWay, Ridgway said he usually asked the women to go into his bathroom to wash their “vaginas” while he watched through the open door. Aside from crude slang, he didn’t know how to describe the female anatomy. He used the word vagina when he meant vulva. He insisted that none of the young prostitutes objected to his watching them through the open bathroom door.

He also urged them to urinate before sex. That way they wouldn’t be as likely to wet his bed when he killed them. Indoors or outside, he had discovered that having intercourse “doggy style” gave him a physical advantage. Entering them from the rear—but never, he insisted, for anal penetration—gave him a physical advantage. After he ejaculated, he sometimes told them “I hear someone,” and they lifted their heads to listen. Or they tilted their heads back as they reached for their clothing. With their throats exposed and extended, it was easy for him to press his right forearm against their larynxes and cut off their breath, choking them.

“If we were outside near the airport, they would look up as a plane went over, and that was when I did it,” he said matter-of-factly. “If my right arm got tired, I used my left, and if they really fought, I would put my legs around them. I told them if they stopped fighting, I would let them go. But I was always going to kill them.”

It was an eerie experience for anyone watching and listening. Ridgway’s voice was tight, as if it was emerging under great pressure, and his words came out in bursts. Even so, he seemed quite comfortable about answering probing questions.

Because the victims meant nothing at all to him, he apparently had no preference about race or body type. He had “dated” some of the women before, but knowing them made no difference to him. “I just wanted to kill them. If they told me to hurry, that made me angry. And I would kill them.”

Many of the girls had pleaded for their lives, telling him they had children at home, a family to take care of, or, quite truthfully, “I don’t want to die.” Of course, it didn’t matter to him. Nothing that the hapless women could do dissuaded Ridgway from his goals. “Some went easily,” he recalled, “and some fought hard, but they all died.” He estimated that even the most violent struggle didn’t last longer than two minutes.

He had never used a gun to kill, or a knife. “It would have been messy, and they still might be able to scream.”

“Why did you choke them?” he was asked.

“ ’Cause that was more personal and more rewarding than to shoot her.”

He was indignant about the young women who had fought him, leaving bite marks or scratches. He had switched to ligatures that gave his arms more protection—anything that was handy or something he had prepared: towels, belts, extension cords, ropes, his necktie, socks, jumper cables, even his T-shirt.

Only one of the girls Ridgway brought to his house had fought him hard enough to escape his bedroom, managing to reach the front door. She was inches away from freedom when he caught her and killed her in his living room. Although it was impossible to know which victim that had been, it was likely that it was Kim Nelson, who was also known as Tina Tomson.

Had they not been attacked when they were completely off-guard, some of the women he killed might well have bested him. Tina Tomson was many inches taller than he was and weighed as much. Marie Malvar was small but she had hurt him badly, scratching him until he bled and leaving scars that he’d had to pour acid over to hide. Marie had made him very angry—so angry that he said he decided to leave her body all alone in a different place from the other girls. Later, he had tried to find her but he’d been consumed with such blind rage when he left her that he couldn’t find her again for a long time.

Even though Ridgway claimed his anger was a natural reaction to having been cuckolded by his second wife, his interviewers knew that during the time after his divorce from Dana, he had had many consensual sexual partners. It hadn’t mattered. He’d still roved along the highways, continually looking for prostitutes.

He described how he planned in advance how he’d get rid of the still-warm bodies of the victims he choked in his bedroom, protecting his mattress with plastic in case they urinated or evacuated their bowels as they died. “If that happened, then I would have to clean up,” he said mildly, “and do laundry. I never closed their eyes or touched their faces. I dragged them out of the house on plastic or an old green rug I had, and put them in my truck. I got rid of them right away.”

Once, he’d put a small woman into a blue metal footlocker that belonged to his son, Chad.

“What did you do with that trunk?”

“Afterward I sold it at a swap meet.”

Wherever he had formed his ethics—or lack of them—about sex, he was alternately lewd and prim. He explained that he considered masturbation a greater sin than going to prostitutes. Sometimes, he’d had no choice but to seek out the women on the street. He didn’t like “labels,” and took offense when any of his questioners called him a serial rapist. “I’m not a serial rapist,” he complained. “I’m a serial killer.”

Ridgway’s stalking hours depended on what shift he was working at Kenworth, his vacation time, or whether Kenworth employees were on strike. He could verify dates by checking his job schedules. His own memories were precise only in his recall about whether the weather was warm or cold, wet or dry, when he picked up his prey.

53

ONE MORNING a few days after Gary Ridgway began his confessions to Green River Task Force detectives, Jon Mattsen and Tom Jensen were puzzled to find a man whose attitude was much changed. As if by rote, Ridgway gave them his breakfast menu, but rather than smiling at them and saying good morning, he turned away and sat with closed eyes, his back to them.

It was June 18, 2003, and his voice was tinged with anger as he said he’d awakened in the night and begun to think. “The Other Gary came into my mind,” he said.

They wondered who the “Other Gary” was, but it soon became obvious that he was referring to a stronger, angrier persona than he had demonstrated so far.

The Other Gary, he told them, was enraged because of the power and control the detectives had over him. “You guys are trying to control me, but I never slept with a dead woman. Sure, I screwed them a couple of times. The ‘New Gary’ wants me to candy-coat this.”

It was apparent that the man they had talked to until this morning was the “New Gary,” a reasonable man who was pleasant and cooperative. The “Other Gary,” who was also the “Old Gary” didn’t want to talk about the murders and resented being controlled.

“I killed them because I wanted to,” the Old Gary said. “I was mad. I killed forty-nine or fifty people between 1982 and 1985. I killed a lot of them because of my rage and anger at my ex-wife.”

Now the Old Gary wanted to go out and find the bodies of his victims. He would call the shots about where they would go. The man with closed eyes stuttered as he said, “I hated ’em—hated ’em.”

It had started, he said, with Wendy Coffield. “I don’t give a shit about where I killed ’em. I didn’t give a shit about them or their jewelry. Carol Christensen meant nothing to me. The fish I put on her were to attract animals. I dragged ’em by their feet. All of them didn’t piss me off. Some I wasn’t mad enough to kill.”

Either this was another personality fighting its way out of the “New Gary” of 2003, or it was a clumsy attempt to present himself as a multiple personality. “I had sex with them afterward. They weren’t human, I guess. I didn’t give a shit. I bit [one of them] on the breast. I didn’t know Mary was pregnant. The New Gary is a wimp.”

Ridgway seemed genuinely angry as he spouted out filthy admissions for half an hour, his eyes squeezed shut. Jensen and Mattsen picked up on the dual method of interrogation the prisoner was suggesting. Perhaps even he couldn’t tell them everything he had done unless he could hide behind “the Old Gary.” That was fine with them. They pretended to respond to this angry man.

“The man who talked to us yesterday, the New Gary, was a real man,” Tom Jensen said, but the personality now onstage wasn’t buying it. The Old Gary was in charge and he insisted that he didn’t let women control him. “I had sex with every one of them but the pregnant one. I dumped a bag with cans [off the bridge] on 216th. Maybe they had prints on them.”

He continued to talk about how much he hated women, interspersing his monologue with details about evidence. “I left some jewelry by a tree near IHOP. I’m in charge now and I’m not gonna take it. I took three or four pictures of women under the Red Lion, and then I tore them up. I did write to the Times or the P.I. Don’t waste your time looking under my houses.

“I killed two ladies after I met Judith.”

Ridgway, whichever version this was, swore frequently although his grasp of scatological words wasn’t very extensive. “Old Gary” or “New Gary,” he had a limited vocabulary. He recalled killing one victim on the floor of his white van, using a cord pulled tight. “They’re all pieces of trash to me—garbage.”

“Why?” Jensen asked.

“Women always had control of me. They used me. I did cry after sometimes, but that was the good part of me. I’m the Old Gary now. The jewelry’s gone. I left it at Kenworth or in the airport and some Laundromat. I left some in a covered part of a light pole, and in a seam in some concrete beside the Safeway, and then I peed in a corner by the fence.”

They let him vent as he jumped from one subject to the next, not sure if this was an act. “That ‘burn’ on my arm isn’t acid,” he said. “It’s where Marie Malvar scratched me. I had scratch marks on my back…. Once I dropped [a victim] on her head off the tailgate.”

Jon Mattsen asked him about the cluster site near Exit 38 near North Bend, but Ridgway wasn’t sure. “I did roll one down the hill at Star Lake,” he said. “I didn’t kill no damn dog. I had control of those bitches. I didn’t have no love. Nobody loved me. So fuck ’em all! The New Gary is too soft. He’s not gonna hurt anyone.”

“What’s the Old Gary gonna tell us?”

Still turned away from the detectives questioning him, Ridgway’s eyes remained closed. “I killed a black lady in Ballard and one by a hospital. I took two to a graveyard by Washelli, and there’s one by Kmart, one by Leisure Time. I did take a head to the Allstate parking lot in Oregon. There was blond hair on the head. There’s three separate parts of bones on that funny-sounding road [Bull Mountain Road in Tigard], but I had a head that I lost.”

This seemingly furious Ridgway told them that he’d worn gloves and switched his shoes from tennis shoes to his Kenworth shoes in an effort to throw them off. He’d replaced the tires on his 1975 Ford pickup so they couldn’t be traced. He’d cut out some newspaper clips for information on what the task force was doing, and said he’d read four pages of a book that had information on evidence. He’d given two earrings to a girlfriend’s daughter. Now he moved on to the girl who got away: Penny Bristow.

“There was one lady I strangled without killing—on 188th. Nice lady. Dark hair. I left her there, naked, and took her purse, but she didn’t have any money. Sometimes I took their wallets and put their money in my pockets.”

He mentioned a woman he’d talked to near the airport, and had “motel sex” with. “I picked her up later and I took her someplace and I killed her. I know that for sure.”

He was probably referring to Keli McGinness, who had never been found. It may have been her severed head he took to Oregon with him, losing it in a culvert near the Allstate building.

The Old Gary was on a roll of rage, but it was sporadic now. “I didn’t hug ’em and kiss ’em at all. I didn’t give a crap about ’em. I had sex with a dead body [near where Connie Naon was found]. The other Gary’s [the New Gary] all screwed up. If you want to know what I did, talk to me. I’m the one who did it. Sometimes I tore up I.D. on the highway and threw it out. For that short time, I was in control. I’m the one with the devil in my head. The New Gary didn’t want me to come out. I don’t have rage anymore, but I got mad last night. I don’t have no rage no more.

“I’m in control now. You put words in his mouth. I didn’t give a shit about sleeping with them. The numbers of victims came from me. I don’t know if the New Gary can get back in. I killed ’em at S.I.R. [Seattle International Raceway], Green River College, 410, Riverton, Highway 18. I didn’t shoot no women. Two on Black Diamond Road, Carnation Road…”

He faltered. “The old one…The new one just flipped back in.”

Gary Ridgway’s voice was softer, tired sounding, but he hinted he had more to say. Mattsen and Jensen tried to bring the Old Gary back, but he wouldn’t come out. It was doubtful that Ridgway was a multiple personality. It seemed more believable that he had seen too many movies about multiples. And, in the Northwest, there had been massive coverage of the tapes of the “Hillside Strangler”—Kenneth Bianchi, arrested in 1980 for serial murders of young women in Los Angeles and Bellingham, Washington. Bianchi had done a very convincing double-personality. Ridgway’s acting wasn’t even in the ballpark.

Still, the session was very productive, if repugnant. Whether it was the Old Gary or the New Gary, he had admitted countless murders provoked by his fury at women in general. He had planned the murders and the disposal of the victims’ bodies.

It wasn’t yet nine thirty in the morning and he had filled the interview room with ugly admissions. The man Mattsen and Jensen had encountered at first seemed to have had his say, but the New Gary wanted to tell them things. He wanted to talk about the death of Giselle Lovvorn, the seventeen-year-old genius whose body was found at the south end of the deserted airport property.

“Chad was with me when I picked her up,” he said. It had been on a weekend, and his son was staying with him.

Jensen and Mattsen exchanged a quick glance. This seemed so far outside the pale of what any father would do. But Ridgway went on talking, and he was currently “the New Gary,” at that. But he assured them that he had left Chad—eight or nine at the time—in his truck while he walked the woman he called “LaVerne” well out of sight. The sex was over quickly, he explained, and then he had choked her with his forearm as a plane flew over.

“To be sure, I tied my black socks together and around her neck, and twisted the knot with a twig until it broke.”

“Did she fight you?” Mattsen asked.

“I can’t remember.”

“How could you kill a woman right in front of your son?” Jensen asked.

“I was in charge,” Ridgway said, but in the New Gary’s mild-mannered voice. “We were out of sight.”

“How long were you gone from Chad?”

“Probably five or ten minutes. When I came back, Chad asked where did the girl go. I just told him she lived nearby and she’d decided to walk home.” He remembered that he took his son someplace, then came back alone to move the girl’s body deep into the weeds.

They took a break. If Ridgway didn’t need one, the two detectives certainly did.

Facing his questioners, the regular Gary was still with them. He apparently didn’t get that whatever persona he affected, his confessions were odious. They had to convince him that nothing shocked them, but that wasn’t true. However experienced Ridgway’s questioners were, it was virtually impossible not to be taken aback by the complete and utter lack of feeling he demonstrated.

He did seem uncomfortable about giving the details of his intercourse with the corpses of the women he’d killed, and, for once, talked around his perversions, avoiding questions he seemed to anticipate.

“We have evidence of necrophilia,” Mattsen said calmly. “You wouldn’t be the first person, or the last, who did that.”

“Yes…I did lie about that. I had to bury them and take them far away so I wouldn’t go back to have sex with them. I had an urge to do that. It was a sexual release that I didn’t have to pay for. Maybe it gave me power over them.”

Ridgway admitted to returning to the bodies of about ten of the women he had left close to the Strip. “That would be a good day, an evening when I got off work and go have sex with her. And that’d last for one or two days till I couldn’t—till the flies came. And I’d bury them and cover them up. And then I’d look for another. Sometimes, I killed one one day and I killed one the next day [and] there wouldn’t be no reason to go back.”

He had returned to one victim to have intercourse with her body even though his eight-year-old son was asleep in his truck thirty feet away. When he was asked what would happen if his son remembered that and threatened to tell, he wasn’t sure.

“Would you kill him?”

“No…I might have.”

Penny Bristow, the one girl who got away from Gary Ridgway, had always felt that he only wanted her dead, and that live sex hadn’t mattered. Even though he’d demanded fellatio, he had no erection. “I don’t even know why he took his clothes off,” she said. “His face looked white, clammy, cold. His arms and everything were cold. His hands. He was a totally different person and he kind of made me think that, if he did kill me, since he wasn’t interested in me sexually before that, he probably would have tried to have intercourse if I was dead.”

DR. MARY ELLEN O’TOOLE may have come the closest to uncovering the early childhood events that had the devastating impact on the way Gary Ridgway viewed women and why he developed the aberrations that consumed him. O’Toole had initially explained that the F.B.I.’s Behavioral Science Unit didn’t have time to consider the cases of every serial killer referred to them, and they didn’t even care about how many victims a man might have taken. “They’re not all equally interesting to us,” she said. “I would need to put you through what I refer to as a ‘verification process.’ ”

It was a challenge Ridgway could hardly have resisted. He had always wanted to be interesting, and he’d been anxious to present his perversions to her.

“At what age did you realize that there was something wrong with you?” O’Toole asked.

He thought it was when he was about ten. His “red flags” were his forgetfulness, his breathing, his allergy problems, and his depression. Dr. O’Toole said that was not what she meant; she was more interested in his paraphilic behaviors, a term she had to explain to him, starting from “personality disorders,” which he seemed to grasp, and linking that to the abnormal sexual desires he had practiced: frotteurism, exposing himself, stalking, voyeurism, rape, murder for sexual release, and, finally, necrophilia.

Although he would deny it for a long time, Ridgway felt that the bodies of his victims “belonged” to him. As long as they weren’t discovered and removed by the Green River Task Force detectives, they were his. “A beautiful person that was my property—uh, my possession,” he told O’Toole, “something only I knew, and I missed when they were found or where I lost ’em.”

“How did you feel, Gary, back in the eighties when the bodies were found and taken away, those times they were discovered,” O’Toole asked. “How did it feel?”

“It felt like they were taking something of mine that I put there.”

That was, he explained later, why he had taken some of the skeletons or partial skeletons to Oregon. It was to confuse the task force detectives because he didn’t want them to find and remove any more of his possessions. He’d often wished he could find some of the old “bottomless” mine shafts that still existed in southeast King County so he would know he had a secure place to leave the corpses of his victims. The bodies were both a burden to get rid of and treasures he wanted to keep.

O’Toole was particularly interested in his relationship with his late mother, and it proved she had good reason to be suspicious. Gary Ridgway had, indeed, had an inappropriate relationship with Mary Ridgway. When he was thirteen or fourteen, she had both humiliated him and sexually stimulated him after he wet his bed, something that happened at least three times a week and sometimes every day. “She said to me, ‘Why aren’t you like [your brothers]—they don’t wet the bed. Only babies wet the bed. Aren’t you ever going to grow up?’ She degraded me. I didn’t feel much love at that time.”