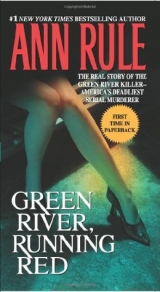

Текст книги "Green River, Running Red. The Real Story of the Green River Killer - America's Deadliest Serial Murderer"

Автор книги: Ann Rule

Жанр:

Маньяки

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

15

THE PATTERN of abduction was moving south—down to S. 216th and Pac HiWay. Both Debra Bonner and Marie Malvar had vanished near the Three Bears, albeit months apart. And those of us who lived in Des Moines didn’t feel nearly as distanced from criminal violence as we once had, perhaps smugly sheltered in our little town that curved around Puget Sound.

Keli Kay McGinness was a striking blonde, a buxom eighteen-year-old with a heart-shaped face and blue eyes with a thick fringe of dark lashes. She divided her time between the Camp in Portland and the Strip in Seattle, sometimes even traveling to southern California. In the early summer of 1983, she and her boyfriend had left Portland to see how things were going in Seattle, hometown to both of them.

WHEN they worked Portland, Keli usually started on Union Avenue early in the evenings, and then moved to the downtown area around eleven PM. She was very self-assured and seemed older than she actually was. “She was at the top of the ladder of the girls on the street,” a woman who had worked in the Camp in the eighties remembered. “Keli wore this white rabbit-hair coat and I could never tell if she wore a wig or whether her hair was just bleached and she used lots of hair spray. She was really friendly with a girl named Pammy Avent, whose street name was ‘Annette.’ Keli had a lot of street names.”

My correspondent, who was a mature woman in a completely straight career when she contacted me, asked that her identity not be revealed as she looked back at the way the Camp was twenty years before. Of course, I assured her that it would not be.

“A lot of the girls were out there for the social aspect besides [being there] to make money—playing video games and visiting with each other at the Fun Center—but not Keli. She was focused on making money. She usually walked alone while the other girls walked in pairs. Keli had this strut and she stared into every car that passed her.”

The last time anyone who knew her remembered seeing Keli McGinness was at seven thirty PM on June 28, 1983, at the now-familiar corner of the Pac HiWay and S. 216th. That night she was wearing a tan short-sleeved sweater, blue jeans, a long camel-hair coat, and very high heels. The Three Bears Motel was on that corner, and the desk clerk’s register showed that she checked in at ten PM.

Keli’s boyfriend reported her missing the next day, but Des Moines police detective sergeant Bob Fox wasn’t convinced that she had met with foul play. He had seen too many adults and older teenagers leave of their own accord. He told a reporter, “There’s no law against a person saying, ‘I’ve had it. I’m leaving.’ I just don’t know, and I don’t think we will know, until we hear from her one way or another.”

Keli was so attractive that people who saw her remembered her, but like Marie and Gail and so many girls before her, nobody along the Strip saw her.

THERE WERE OTHER CASES that might or might not be connected to the series of disappearances in 1983, and the murdered victims in the last half of 1982, enough cases that it set investigators’ teeth on edge, wondering just who might be out there, always alert to vulnerable females.

On July 9, 1983, King County patrol officers took a report from an eighteen-year-old secretary who had been violently raped. She was a classic victim: a little intoxicated, upset over an argument with her boyfriend, so upset that she stomped away from their table at Anthony’s Homeport restaurant at the Des Moines marina. She’d been served alcohol because she carried fake I.D. Crying and angry, she was in a phone booth calling friends for a ride home when a stranger in a pickup truck pulled over and asked if she needed a ride.

She shook her head and tried to pull the folding door closed, but the man grabbed her and forced her into his truck before she could react.

“I’ll take you anywhere you want,” he said, now oddly polite.

She gave him her boyfriend’s address in tony Three Tree Point, hoping against hope that she would spot him on his way home and he would save her. The driver followed her directions but he drove right by the address, ignoring her protests. He headed toward the small town of Burien, grabbing her hair in his fist and telling her he would kill her if she tried to escape. In Burien, he parked on the grounds of a boarded-up school and raped her. Fighting him, she was finally able to hit the door handle and tumble out of the truck. She ran, and a nearby resident responded to her frantic knocking.

Treated in a hospital’s emergency room, the frightened girl could tell officers only that the man told her his name was “John.”

“What did he look like?”

She shook her head. “I don’t know. It was too dark.”

There was no suggestion that this victim was working the streets. She had simply been in the wrong place at the very wrong time. Her description of the pickup truck was similar to the trucks seen on Pac HiWay.

Keli McGinness’s last-known location was about two miles from the Des Moines marina. Two disturbing incidents nine days apart. Ironically, the articles about both eighteen-year-olds shared space on the front page of the Des Moines News.

ON MAY 8, 1983, King County detectives had quietly investigated the discovery of a woman’s body in a location some distance from the Green River and the Strip. The circumstances surrounding this body site were so bizarrely ritualistic that they had first thought it had to be an entirely different killer. And the investigators were scrupulous about not releasing full information on what they found. Should they encounter either the actual murderer or a compulsive confessor, only they and the true killer would know these details.

Carol Ann Christensen, twenty-two, was the single mother of a five-year-old daughter, and she’d been excited on May 3 because she had finally landed a job after a long time of looking for work. Carol Ann lived near the Pac HiWay, and she shopped there, on foot because she had no car—but she was definitely not a prostitute. Her new job was as a waitress at the Barn Door Tavern at 148th and the highway. It was close to the White Shutters, the restaurant/bar that attracted singles, and only two or three blocks from the small mobile home park where Carol Ann lived, close enough that she could walk to work.

CAROL ANN had worked only a day or two when she failed to come home one night. Her mother was frantic. Carol adored her little girl, Sarah, and would not have deliberately left her. If she could get home to Sarah, she would have.

The terrible answer to where Carol Ann had gone came within a few days. Carol Ann Christensen’s body was discovered in an area known as Maple Valley, which is about twenty miles east of the airport Strip. Much of Maple Valley would be built up in the next twenty years, but it was heavily wooded when Carol Ann disappeared. A family searching for edible mushrooms had to go only a short distance off the road into a shady patch of salal, ferns, and fir trees to find the precious morels and chanterelles bursting from the woods’ leafy floor.

They forgot all thoughts of mushroom-hunting when they came upon a grotesque tableau. A woman lay on her back in a half-sitting position, but they could not see her face. Someone had pulled a brown grocery bag over her head. Her hands were folded across her belly, and they were topped with ground sausage meat. Two dead trout, cleaned and gutted, lay vertically along her throat. A wine bottle that had once held Lambrusco had been placed across her lower abdomen.

This was a “staged scene,” not uncommon to sexual psychopaths. It is a way to taunt detectives, silently saying “Catch me! Catch me!” And at the same time, announcing, “Look at how clever I am, and you don’t even know who did this. You can’t catch me!”

Carol Ann wasn’t in the river, and she hadn’t been left close to the Pacific Highway. She was not a prostitute. Still, like the first Green River victims, she had been strangled by ligature, in her case with a bright yellow, braided plastic rope, which her killer had left behind.

She was fully clothed in jeans; a Seattle Seahawk shirt; a white, zippered, polyester jacket; and blue-and-gray running shoes. The grocery bag said “Larry’s Market” on it, the high-end supermarket located on the Strip.

Carol Ann Christensen’s murder was originally investigated by the Major Crimes Unit of the sheriff’s department, rather than the Green River Task Force, because both her lifestyle and the M.O. in her death were so different. Later, when her address and employment indicated she had lived and worked right in the kill zone, it was quite possible that she might well belong on the list with the other victims.

Although it is rare for serial killers—and by 1983, the Green River Killer was referred to that way—to murder someone they know personally, it is not unheard of. Carol Ann Christensen might have believed that she was going on a date, a picnic, with someone she knew and trusted. She was dressed for a picnic and the Maple Valley woods where she was found were pleasant in the spring. But even though her body was not that far from the road, the woods were dark and there weren’t that many people around. If the man she was with took off his deceptively friendly mask and began to hurt her, her screams for help would not have been heard.

Eventually, Carol Ann’s name went on the ever-growing list of possible victims of the Green River Killer.

It was fortunate that the King County investigators had followed their usual triangulation measurement routine in the Maple Valley woods. No one would recognize them now. They have become a sprawling neighborhood of modern homes called Patrick’s Faire.

There would be no more bizarre staged body sites. Whatever point the killer had wanted to make had evidently been accomplished. As Pierce Brooks always did, the task force investigators kept trying to put themselves into the mind of the killer, to think as he thought, to walk where he walked, but it was very, very difficult.

He didn’t think like anyone they could ever imagine. He wasn’t crazy, of that they were sure. If he was insane, he would have made some misstep by now, flipped out and done something to make them notice him. Instead, he was still playing his bizarre, malignant games.

16

ALTHOUGH her boyfriend insisted that Keli Kay McGinness would have contacted him if she was okay, out of all the young women who had disappeared, the task force and her own girlfriends figured that Keli had made it out safely. She had sometimes hinted that she might just change her lifestyle and go for something more rarefied, and she had told her mother that if she ever really got out of Seattle, she wouldn’t be back.

She had the looks and the brains to accomplish that. And, surprisingly, Keli had the background that would let her slip easily into an upper-class milieu. Her whole life had been a study in contrasts. She’d grown up too fast, though, maybe because she had too many father figures, perhaps because she had gone from hard times to wealth and back again.

Keli’s birth parents were attractive, personable, and doing well financially. Her father was a handsome and garrulous car salesman, well known in the south end of King County, who earned good money. Her mother was a beautiful singer with high hopes of becoming a star.

In 1984, Elizabeth Rhodes, a Seattle Times reporter, did a remarkable reconstruction of Keli’s life. Rhodes, who is now the Times’s reigning expert on real estate, hasn’t forgotten the young woman she wrote about two decades ago: “Keli isn’t easy to forget,” she told me. “You have to wonder where she is now.”

Like my own daughter, Leslie, Keli was born in Virginia Mason Hospital in Seattle. Keli would use many street names and many birthdates, but her real birthday was April 17, 1965, and if she is alive, Keli would be in her late thirties now.

Her parents’ union lasted until she was two and a half and her mother was twenty-seven. By accepting small gigs in local venues, Keli’s mother was able to support the two of them, and they grew very close. Like the popular song by Helen Reddy, Keli was one among many of the missing girls who had bonded early with their mothers—“You and Me Against the World.”

Two years later, Keli’s mother married an entrepreneur whose fortunes were soaring. He was more than willing to share his wealth with his bride and new stepdaughter. They all lived on Queen Anne Hill in a virtual mansion, a home that would cost well over two million dollars today. Keli Kay had sixteen rooms to romp through, and she could sit on a padded window seat and gaze through bay windows at downtown Seattle and the ferry boats on Puget Sound.

The pretty little girl had her own horse and riding lessons, music lessons, weeks in exclusive summer camps where other rich girls went, and orthodonture that corrected her slight overbite. Her hair was brown then, and her grade school pictures show her smiling carefully so her braces wouldn’t show.

As her stepfather’s business acumen increased, both of Keli’s parents worked long hours. She often spent more time with a babysitter and housekeeper than she did with her mother and stepfather, but she was a bright child and she got A’s in school and won spelling bees. She was lonely a lot of the time, but she adored her mother and was especially happy when they were together.

“We were very, very close,” her mother told Elizabeth Rhodes many years later. “I loved her as a daughter, but she was also fun to do things with. The best thing about Keli was her wonderful personality. She had a witty personality, quick and sharp.”

The small family had lots of good times—trips to Hawaii and Mexico, cruising on their fifty-foot yacht from Elliott Bay to the San Juan Islands—and mother and daughter had all the wonderful clothes they wanted. It was a lifestyle few Seattleites enjoyed. It lasted only five years. Then her mother and stepfather divorced, and the life that Keli Kay had thrived in was over, a quick curtain dropping down on her world of privilege. She and her mother went back to an ordinary existence.

She was almost eleven then, a particularly disturbing time for young girls. More than the wealth and all that came with it, Keli Kay had to feel that her stepfather had divorced her, too. Her father had left her, and now another father figure walked away from her. To salve her own feelings, she blamed her mother for the divorce.

Quite soon, her mother married again. This stepfather wasn’t rich and he wasn’t very nice. Her mother came home from work early one day and caught him throwing a rocking chair at Keli. Her leg was already bruised from a beating with a wooden coat hanger. That was the end of that marriage; her mother would not allow anyone to hurt Keli.

Keli was thirteen, an age when even girls in stable families act out and become “different people.” Any parent of a teenage daughter can attest to that. And Keli had lost too much, too rapidly. Her grades dropped and she began to run away from home—but only for a day or two. She, who had always been an obedient and fun child to be around, became sullen and defiant. She was still smart and still creative, but she saw the world through a dark cloud now. Life had betrayed her.

Keli had also suffered the worst experience any young teen can. She was babysitting when she answered the door without checking to see who was there. It was five teenage boys, drunk and rowdy. They pushed their way in and Keli went through a horrendous ordeal of sexual attack—a gang rape.

At three AM, her mother got a call to come to a Seattle hospital and found her thirteen-year-old daughter traumatized to the point that she couldn’t speak. Keli had known some of the boys and was afraid of them, because they were leaders in the wilder crowd at a local high school. If she agreed to testify against them in court, she thought they would hurt her more. And besides, she was ashamed.

Keli wrote a poem a little while later, a poem her mother didn’t find until she had run away from home for good. Elizabeth Rhodes quoted it in her article:

“Looking back through the pages of yesterday,

All the childhood dreams that drifted away

Even the box of crayons on the shelf

Reflect bits and pieces of myself…

She was only fourteen when she wrote that, regretting that she “had to grow up.” Her life as she knew it was over, and there were hints that growing up hadn’t been the usual maturation that the years bring. She ended her poem:

“But I know now in my heart and mind

I had to leave it all behind

And as a tear comes slowly to my eye,

I stop and ask myself,

Why?”

–Keli K. McGinness

And then Keli McGinness was on the streets, as if somehow the pain would lessen there. She bleached her hair and wore clothes that played up her D-cup bust. If you can call it that, she was a success, working the Sunset Strip in Hollywood, The Camp in Portland, and coming home to Seattle’s Strip. She fell in love with an African American boy two years older than she, and she was pregnant at fifteen.

Keli Kay carried two babies to term before she was eighteen. Unlike Mary Bridget’s, both of Keli Kay’s babies survived.

Did Keli herself survive? Probably not; her status is still in limbo. Her first baby, a boy, was born in California. She brought him home to Seattle to show to his two grandmothers. His paternal grandmother offered to look after him, but Keli decided that he should be adopted, and he was.

But both teenage parents regretted that, and within six months, Keli was pregnant again. They had planned this baby as much as they were capable of planning in a lifestyle that involved constantly moving and living in cheap motels. Somehow they thought that keeping this second baby would make their love stronger and impress their families that they were mature.

It was a little girl, a lovely baby girl who combined the most attractive features of both her young parents. Again, the father’s mother was willing to help raise her, but Keli’s mother had never been able to accept her daughter’s boyfriend. She blamed him for Keli’s lifestyle, and she was opposed to a biracial union. Keli told her she was prejudiced, which she was, but only because of what she felt Keli’s lover had done to her.

She had pleaded in vain with Keli to leave the streets. She didn’t have to have a pimp/boyfriend. Her mother would help her. They were still friends as well as mother and daughter, although Keli was the worldly-wise one as her mother struggled to cope with what Keli had become. Still, they stayed in touch with each other, talking in the way people do whose experiences with life barely touched. They loved each other, but they couldn’t help each other.

Keli tried to explain, “I’m a prostitute, Mom. How could I ever make the kind of money I am making now doing anything else?”

As her acquaintances from The Camp recalled, Keli did make top dollar. When it wasn’t raining and cold out, the girls in Portland and Seattle could bring in more than $3,000 a week, although most of it was turned over to their pimps. Ironically, Keli’s childhood, when she had moved easily among the wealthier members of Seattle society, gave her a polished image that attracted the richest johns.

But she couldn’t do that and take care of her four-month-old baby girl, too. She was doing fine so far, and between Keli and her boyfriend, someone was always with her. But Keli knew she wasn’t in a position to be a full-time mother. She took her baby to a religion-based child-care agency. No, she did not want to put her up for adoption. Keli asked that she be placed in a foster home, but just long enough for her to serve some jail time for an earlier prostitution arrest that was hanging over her head. She couldn’t say exactly when she would be back to pick up the baby, but she insisted she was coming back. There was no longer someone in either her family or her boyfriend’s family who was able to care for the infant, although they all said they loved her.

Keli McGinness showed up at the jail on May 25 and served her seven days, secure in her knowledge that her baby was already safe in a foster home.

Although both their parents disapproved—his mother was unable to even say the word prostitution—Keli’s boyfriend picked her up from jail in his six-year-old Cadillac convertible and they drove to Portland, a regular pattern along “the circuit” for them. He waited in a restaurant lounge, as he always did, for Keli to come back with the money she had earned. As all the “boyfriends” of the missing women have said, he “really loved her” and worried about her, afraid she might meet some weirdo.

Keli herself felt fairly safe, even though she knew about the Green River Killer. She would not get into cars; she took tricks to motel rooms that she rented. She told people who loved her and cops who arrested her that “It won’t happen to me.”

Keli considered arrests part of the cost of doing business, and she was philosophical about fines and the jail time she occasionally had to serve. By adroitly changing her names, birth dates, and identification, she managed to skate free many times because the arresting officers couldn’t find her current name in their records. But sometimes she got caught, and she would shrug her shoulders and accept the law’s edicts, laughing as she said, “You got me!” She knew most of the vice detectives and she was polite with them, accepting the fact that sometimes it was their turn to win.

The vice cops did win in Portland on June 21, 1983, and Keli spent three days in jail in Oregon. Her legal schedule was crushing, though, and she had to be back in Seattle for a court appearance on June 28. She told her attorney that she would be back in time for that, but she didn’t show up, and the judge ordered a bench warrant for her arrest. According to her boyfriend, they had come back to Seattle, but for some reason Keli didn’t want to go to court. Instead, they spent that day together.

And then Keli checked into the Three Bears Motel. The desk clerk verified that. Her room cost about $22. A little after nine, she was on Pac HiWay, strolling down toward the Blockhouse Restaurant where the clientele, mostly Des Moines residents attracted by the prime rib, fried chicken, and the senior citizen discount, were having dessert, or sitting in the crowded bar as the live entertainment began. She wouldn’t have found any johns there, but cars coming off the I-5 Freeway at the Kent–Des Moines exit would slow down at the sight of her.

Keli McGinness never returned to pick up her baby girl from the church agency. The baby’s father said he didn’t get any of the messages that the agency left for him. Their fourteen-month-old daughter was too young to know that her mother was gone, and there was no one else in the family who could take care of her. Keli’s baby girl was adopted when no one came for her.

Keli’s mother hadn’t seen her since Mother’s Day, 1981, when Keli drove to eastern Washington to see her. She hoped against hope that her daughter had decided to get lost somewhere far away. At least that would mean she was alive.