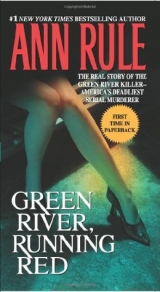

Текст книги "Green River, Running Red. The Real Story of the Green River Killer - America's Deadliest Serial Murderer"

Автор книги: Ann Rule

Жанр:

Маньяки

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

DEBRA LORRAINE ESTES disappeared on September 20, 1982. She had just passed her fifteenth birthday. The last time her family saw her, she had dark hair permed in a Jheri curl close to her head, and wore little makeup. Debra had run away from home many times, and her mother, Carol, worried herself sick over her while her father went out looking for her. She was a wild child who was impossible to rein in. One of her relatives, who sometimes let Debra stay a few days when she was upset with her parents, tried to explain. “Life was a game to Debra.”

Although her parents didn’t know it, Debra had gotten a prescription for birth control pills at Planned Parenthood when she was only ten. She routinely added four years to her age, and there was no law requiring that parents be notified when teenagers asked for birth control advice.

The last time Debra’s parents had reported her as a runaway was in July 1982. They were never really sure where she was or whom she was with, although that wasn’t for lack of trying on their part. That July, she had come home with a friend who was a few years older than she was, Rebecca “Becky” Marrero. Debra asked if Becky could move in with the Estes for a while, but Carol Estes had to say no, that wasn’t possible. That angered Debra and the two girls left.

Becky found an apartment in the Rainier Vista housing project, and Debra moved in with her. Through Becky, Debra met a number of men in their twenties. Some were even older, including her boyfriend in the summer and fall of 1982. Actually, “boyfriend” was a euphemism. Sammy White* was a pimp. He and Debra stayed at most of the familiar motels along Pac HiWay: the Moon-rise, Ben Carol, Western Six, and the Lin Villa in the south end of Seattle. Whether Sammy knew she was only fifteen isn’t known.

The Esteses had had three children, but they’d lost their son, Luther, in an automobile accident. And now Debra was missing. Their other daughter, Virginia, worried with them.

As young as Debra was, she had nevertheless been booked at least twice into the King County Jail, and her mug shots looked like two different people. The most recent one showed a girl with golden blond hair, wearing very heavy eye makeup and bright red lipstick. Even her own mother would have had trouble recognizing her. Blond or brunette, Debra was extremely pretty and very petite, but her young life was troubled.

She went to a King County deputy some time in September 1982, telling him that she had been hitchhiking on the highway when a man in a white pickup truck opened his door and agreed to take her to the SeaTac Mall on S. 320th Street. Instead, he had driven to a lonely road and forced her to perform oral sex and then he raped her. He had stolen what money she had. But when Debra Estes reported the sexual assault, she used her street name: Betty Lorraine Jones. She told detectives Spence Nelson and Larry Gross that the rapist was about forty-five, five feet eight inches tall, and had thinning brown hair and a small mustache.

When the two detectives located witnesses who had seen the truck going in and out of the wooded area Debra described near 32nd Avenue South and S. 349th Street, she agreed to file charges. It was about September 20 when Larry Gross picked her up at the Stevenson Motel in Federal Way and took her to the sheriff’s office to view “lay-downs” of mug shots of suspects. Spence Nelson drove her back to the motel. Neither detective knew Debra by her real name. She was “Betty Jones” in the pending case, a witness who had suddenly bailed on them.

Sammy White was in the motel when she got back. They were a couple now, but it was the usual setup where Debra made the money and he “protected” her. She dressed that night to go to work. White would recall that she wore dark slacks, a dark gray or black V-necked sweater shot with glittering gold or silver threads, and a dark pink thong. She told him she hoped to make enough to pay for a larger unit with a kitchenette so she could cook supper for them.

Debra’s hair was newly dyed jet black, and she wore earrings but he couldn’t describe them. When Debra didn’t come back, Sammy waited around the Stevenson Motel for two or three days and then moved out. The owner cleaned the room, put Debra’s clothes into a plastic garbage bag, and moved them to a storeroom until she could come to pick them up.

As the months passed with no word at all from Debra, her father prowled the seamy streets near the airport. Tom Estes even tried to infiltrate the world that had snatched his daughter away, desperate to find someone who might have seen her. He was alternately angry with the police and despairing, afraid he would never see her again.

Fae Brooks and Dave Reichert would eventually contact more than a hundred people who knew Debra Lorraine Estes/Betty Lorraine Jones. They learned she had been in way over her head, spending her days and nights in some of Seattle’s highest crime areas, appearing to be eighteen or twenty when, in reality, she was only fifteen. They managed to list some possible witness names, but more often the two detectives were given the runaround by people who wanted nothing to do with the police.

Sammy White was the shiftiest. He was living here, there, and everywhere. They finally caught up with him while he was living with his sister. Like most of the pimps they had questioned, Sammy put on a sanctimonious face as he bragged that he’d managed to get Debra off Ritalin (speed). “I warned her that being out on the streets was dangerous,” he said.

The big question was: Was Debra Estes really missing? Or had she simply decided to move on to California or some other place? She was young and capricious; if, as her aunt said, she saw life as a big game, then new adventures might have seemed exciting. Still, Debra had Sammy White’s initials tattooed where they would always show. She must have cared about him to get that permanent mark. Would she have left him without saying good-bye?

Fae Brooks sometimes felt that Debra was still in the area, especially when new information came in on sightings. Someone registered at the Western Six Motel in her name as late as December 2, 1982. She was apparently with her friend Rebecca Marrero at that time.

LINDA RULE turned up missing six days after Debra Estes. But she had been living in the far north end of Seattle, near the Northgate Shopping Mall, more than thirty miles from where Debra was last seen.

LINDA JANE was sixteen years old when her family virtually disintegrated. Her father, Robert, and her mother, also named Linda, divorced and Linda turned to life on the streets. Her younger sister, Colleen, who idolized Linda, stayed with their mother. The girls looked nothing alike; Colleen was tall and hearty-looking with pink cheeks—like their father. Linda was a petite, fragile girl who resembled their mother, except that she was a little taller and she bleached her hair a very light blond.

Sometime between two and four in the afternoon on Sunday, September 26, Linda left the room she shared with her boyfriend at a small brick Aurora Avenue motel. She wore pin-striped blue jeans and a black nylon jacket. She walked north, headed for the Kmart, where she planned to shop for clothes. Linda’s street name was “Ziggy,” after the cigarette papers used to make marijuana joints. It never seemed to fit her; she was softer and more feminine than that.

Linda’s boyfriend wasn’t particularly upset when she didn’t come home that night. “I assumed she’d been arrested,” he told Seattle police detective Bob Holter. “It was daytime, and she wouldn’t have been ‘working’ on Aurora in the afternoon.”

Linda had a lamentably familiar background. She’d dropped out of junior high school, and she was a moderate drug user—marijuana and Ritalin—but she was happy the day she left the motel. She and her boyfriend, Bobby, twenty-four, were planning to get married and she hoped they could have a regular, “normal” life.

Bobby looked for Linda in all the places he figured she might be. She wasn’t in jail—she hadn’t been arrested for prostitution or for anything else—and none of her friends had seen her. He kept careful notes on his search for her, and made a missing persons report.

DENISE DARCEL BUSH, twenty-three, was from Portland originally, and she sometimes traveled to Seattle to work for a few weeks. Portland is 180 miles south of Seattle, less than a three-hour drive. Young prostitutes were a little frightened in Oregon, but they figured that the killer was striking only in Seattle.

In Portland, the street girls called their work area “The Camp.” They worked downtown between 3rd and 4th to the east and west, and Taylor and Yamhill to the north and south. Now that vagrants had taken over much of Burnside Street, most of the women rented motel-apartments by the week up on Broadway.

“All they had to their names,” a onetime prostitute recalled, “was a pack of cigarettes, the motel key, and some change. Their pimps would wait for them down in the Lotus Bar, and they got the real money. They had Jheri curls and Adidas outfits and real leather coats. A lot of the girls wanted to go to Seattle because they heard the money was better up there.

“I was older so I usually worked the hotel lounges. When a girl was gone for a while, I didn’t pay attention—because I figured they’d gone to Seattle or Alaska. Funny how we assumed they just went on with their lives when, in reality, they were missing or dead….”

Denise Darcel Bush had gone to Seattle in the fall of 1982. She had a “boyfriend,” but she was alone the last time anyone saw her on October 8. She was crossing the road on Pacific Highway South and S. 144th, a corner that was proving to be the epicenter of the ballooning number of cases. Like so many of the girls who were disappearing, Denise left in the middle of life. She was going on a short errand to a convenience store to buy cigarettes. In the past, Denise had suffered bouts of epileptic seizures, but they were controlled with medication. At some point, she’d had a medical procedure involving her brain and her skull had a small hole in the bony process there, but she rarely thought about it. Only people close to her knew about it.

Denise was seen on one side of the highway, but she never made it across, or, if she did, no one who knew her ever saw her after that.

So many young women were disappearing, yet it was impossible to verify that they were gone against their will.

SHAWNDA LEEA SUMMERS, eighteen, went missing on October 7 or October 8 from the very same intersection—either the same night as Denise or the next day. The date was fuzzy since no one reported Shawnda missing for almost a month. Alarms were not really sounded yet because it was so difficult to tell the missing from those who had taken to the road to find better turf.

And then Shirley Marie Sherrill seemed to have evaporated from her usual haunts, too. She was nineteen, a lovely looking girl with light brown hair and hazel eyes, who was five feet nine and weighed 140 pounds. Shirley sometimes worked The Camp in Portland, Oregon, but her home city was Seattle. And that was where one of her close friends and co-workers saw her just before she disappeared on October 18. They had lunch before they set out to work—Chinese food in Seattle’s International District. But they weren’t secretaries or lawyers, and their “work” was out on the street.

“THE LAST TIME I saw Shirley,” her friend remembered, “was in Chinatown. She was talking to two men in a car. She looked really nice that day, and I assumed that she was going to go with them, but then I got picked up. And I never saw her after that.”

On Christmas Eve, 1982, a young woman named Trina Hunter went missing from Portland. Trina’s cousin would recall that she never wanted to be on the streets, but older male step-relatives had forced her into it. “They kept her locked up in the attic—one of those where you had to put a ladder up to get out of,” the cousin said. “They beat her, and only let her down to go to work. She tried to go to the police but nobody ever believed her.”

The landslide of human loss was accelerating, but it continued to be sub rosa. The people the lost girls associated with didn’t particularly like or trust police and were reluctant to approach them with missing reports.

BACK IN KING COUNTY, Washington, dark-eyed Becky Marrero, twenty—Debra Estes’s good friend—had been gone from White Center, a district west of the SeaTac Strip, since December 2. Becky often left her year-old baby, Shaunté, with her mother, and she sometimes said that it would be better for the baby if her mother adopted Shaunté. On the day Becky left she turned back to her mother and said somewhat inscrutably, “I’m going to be gone for a long time, and where I’m going, I can’t take a baby.”

Her mother thought she was joking or lying, and besides, Becky didn’t pack a suitcase, but took only a small blue carry-on-type bag with an extra pair of slacks, a blouse, and her makeup. She asked her father for twenty dollars to pay for a room for one night, and he gave it to her.

Becky Marrero was planning on taking a bus, her usual mode of transportation. Her mother believed that she had gone out to make some money for Christmas, but she never came back. Detective Fae Brooks established that Becky had registered at the Western Six Motel through December 1, 1982. And, of course, someone had signed Debra Estes’s name in the guest log as being in the same room with Becky.

Even though there were reported sightings of Becky Marrero after that, none of them could be validated.

IT IS LIKELY that the last Washington State disappearance of 1982 occurred on December 28, when Colleen Renee Brockman vanished. Colleen was only fifteen, a rather plump and plain girl whose photographs show her in jumpers and turtleneck tops. In one, she is wearing braces and holding a stuffed doll.

Colleen lived with her father and brother near the Lake Washington Ship Canal in the north end of Seattle. She had run away a couple of times before, only to come back within a few days. This time, there was no question that she meant to go. No one was absolutely sure why she had left; she had a crush on some boy, and she may have wanted to be with him.

Colleen took a lot of things with her, enough so that her father filed charges against her in the hope that it might bring her to the attention of law enforcement more quickly, and that she might get some juvenile court–required counseling. All of her clothes were gone, all of her Christmas gifts, and also her family’s stereo and some money.

One of Colleen’s friends, Bunny, had run away a few years earlier, when she was only thirteen. “I was abused,” Bunny remembered a long time later. “I had to leave. I had no choice.”

Colleen’s father always felt that Bunny had somehow lured his daughter away. That wasn’t true. Bunny had nothing at all to do with Colleen Brockman’s leaving home. She hadn’t even been in contact with her. But Bunny considered herself lucky; she never had to walk the streets, and always found a place to stay. “God was good to me,” she said gratefully.

Bunny hadn’t seen Colleen Brockman for about three years when she ran into her old friend. Colleen had told other friends that she was miserable at home, but she hadn’t gone into specifics, or if she had, they were not forthcoming with detectives about her reasons for leaving. She didn’t tell Bunny either, but she seemed thrilled to be out on her own. Bunny realized that Colleen was prostituting herself.

“I was about seventeen the last time I saw her,” Bunny said. “She told me what she’d been doing and I was instantly terrified for her. She seemed very happy with her new life, though, and she said most of the guys were really nice to her—buying her presents and taking her to dinner. She was pretty naive. I think she thought that meant they loved her in some way. I told her she shouldn’t do that because she might get hurt. She admitted to me that one guy raped her. He told her that if she did everything he told her to do, he wouldn’t hurt her, so she did, and he let her go. She said it would never get worse than that.”

But just before the dawning of the new year—1983—it looked as if something much worse had happened to Colleen Brockman. Despite her father’s missing-person’s report and his criminal complaint, she was not found immediately and she didn’t come back home.

The other girls who were working the highway didn’t really miss Colleen because they didn’t know her very well. “She didn’t fit in,” one of the Strip regulars said. “The guy she was with wasn’t really…ahh, he didn’t know—They were just trying out the lifestyle, and it was a much bigger sacrifice than she was prepared for.”

Christmas of 1982 was such a sad and anxious time for so many families. Some knew their daughters were dead; others had no idea where they were. Were they being held captive somewhere? Were they being tortured? Maybe they’d been sold into white slavery. In a sense, it was easier for the families who had held funerals and knew where their daughters, sisters, and cousins were buried. The ones who waited agonized, but occasionally they could still feel a small glimmer of hope.

There wasn’t an extended “official list” yet because no one knew just how many names would be on it. And most of the girls who had escaped with their lives in late 1982 considered themselves just plain lucky, yet still nervous about making a police report.

Penny Bristow* had been working at a minimum-wage job near the SeaTac Airport in November. When she ended her shift, it was dark and looked like rain and she dreaded the walk to her apartment. She was in the early stages of pregnancy and didn’t feel very well, anyway. She could have hailed a cab, but that would take more than half of what she’d made that day. So she stuck out her thumb.

A man in a pickup truck stopped to pick her up near S. 208th Street, and she could tell he was looking at her speculatively, wondering if she was a working girl. She knew that world, and she was trying to avoid it. But when he offered her $20 for oral sex, she agreed. She needed the money. Artlessly, she asked him if he was the Green River Killer, and, of course, he said he wasn’t. He even showed her his wallet with money sticking out, and flashed various pieces of I.D., one from his job.

She agreed to go into a nearby woods with him.

Though it was November and chilly, he wore shorts instead of trousers. She knelt to perform oral sodomy, but he was apparently impotent and didn’t become erect. That angered him, and he suddenly reached down and knocked her into the dirt and leaves with his fist, trying to push her face into the ground. She felt suffocated and fought back with everything she had, at the same time pleading with him to let her go. She wished mightily that she had walked home in the rain because now she feared she was going to die.

He was shouting at her that she had bitten him on the penis, which wasn’t true. Somehow, he had gotten behind her and she felt his arm, surprisingly strong, around her neck in a choke hold. She kept struggling and begging him not to kill her.

For an instant, he loosened his grip to get an even stronger pressure against her neck arteries and Penny managed to duck and twist away from him. She ran faster than she had ever run before. He tried to follow her but his shorts, around his ankles, tripped him up. By the time he pulled them up, she had raced up to a mobile home and pounded on the door, screaming. She was hysterical and sobbing as the people let her inside.

When Penny finally did tell the Green River detectives about what happened to her, her memory was still very precise.

The man had been white, in his thirties, with brown hair and a mustache.

11

HE WAS A STRANGE LITTLE BOY who seemed half-formed, a newt in a world of stronger creatures. It wasn’t that he was missing any features or limbs, but his face was like a bland pale puppet’s with deep-set, painted-on eyes. His dark hair flopped lank across his forehead and there was already a faint vertical dent above his nose. He was a slow child who took a long time to commit most things to memory, his recall full of gaps.

He often felt that he didn’t fit into his family because there wasn’t anything special about him. His parents had other kids and they always had dogs and so many cats that he couldn’t remember all their names. School was very, very difficult for him. He could not understand how anyone was supposed to read when all the letters were jumbled around. Other kids in his class saw words, but he didn’t.

He was one of those students who sat either in the back of the class where he wouldn’t bother the other kids, or in the front where the teacher could keep an eye on him.

Although he couldn’t actually remember it himself, his father sometimes talked about the time he had almost drowned, or at least his parents thought he had drowned, and how scared and upset everyone was, and how grateful they were to find him alive and not drowned in the water at all. That made him feel somewhat better—that they must really care about him, although it didn’t seem like it. His mother was very efficient and busy, and his father came home from work and sat in his easy chair and watched television.

The boy was a bed wetter and that was humiliating. It wasn’t so bad when he was really little because other kids wet the bed, too. Probably even his brothers did. But he couldn’t seem to stop, even after he was out of grade school and into junior high.

After a while, his mother got annoyed with him and told him she couldn’t understand why he made so much work for her. She didn’t yell at him, but she set her mouth in a tight, annoyed grimace so he knew she was displeased. He helped her strip his bed, and then he had to go sit in a tub full of cold water while she washed his legs and bottom and his pee-pee.

He had allergies, too, and his nose was always running. If he wiped it on his sleeve, his parents told him that was filthy, but he didn’t always have a tissue.

They usually lived in nice enough houses, but they moved so often that he always felt unsettled. He never really got to know the other kids in his class at the Catholic elementary school. Sometimes he had fun playing, but he always felt kind of sad or maybe angry because it seemed he had so many things wrong with him. He remembered that when he was seven or eight, he was always getting lost. That was mostly when they lived in Utah. He didn’t know why but he couldn’t seem to orient himself when he wandered too far away from home—and had trouble finding his way back.

One time, he had a “big, huge side ache,” and he literally thought he was going to die. There was no one around where he was, and his side hurt so bad that he just had to lie down and rest for at least two hours. And when he was finally able to walk home, he was in trouble for being so late, and no one would listen to him when he tried to tell them that his belly hurt him so much he couldn’t move.

He often thought that he was going to die of something before he was twenty-one. Everything he did turned out bad: his school-work, his bed-wetting. He didn’t fit in anywhere, not even in his own family. He suspected that his parents had brought the wrong kid home from the hospital because he wasn’t like his brothers. If he didn’t come home at all, he figured nobody would miss him much.

Somewhere around this time they moved up to Pocatello, Idaho, but things weren’t any better. He wasn’t very big and bullies picked on him. There was one boy at his new school named Dennis who used to wait for him in an alley after school and beat him up. When he came home with his clothes torn, his nose bloodied, and his face scratched, his father got angry. Not at Dennis, at him.

“If you come home one more time beat up,” his father warned, “I’ll beat your ass myself.”

Then his father softened a little and taught him how to fight. He showed him how to put his hands up and to jab and punch, so he didn’t just have to stand there and let Dennis hit him.

“I got Dennis down on the ground once,” he said, “and held his arms, and I could tell my dad was watching and he was smiling.” He and Dennis were both crying by then, but his father seemed pleased as he walked back to his gas station a block away.

But, somehow, he was still angry. He would think about things he could do to other people to hurt them. He was a pretty good fighter now. He learned he could hold his opponents on the ground and keep them from moving if he put his feet or his knees on their shoulders.

Then he flunked school and was held back. That made him so mad that he pegged rocks at the school’s windows and smashed a lot of them.

More and more, he fantasized about violence. It had been so satisfying to beat up Dennis and to hear the school windows shattering, and to get away with it.

He started setting fires when he was about eight—not houses, but garages and outbuildings. He found some newspapers stacked in a garage a few houses away from their house on Day Street, and he was playing with matches and set the fire. He heard the fire engines coming as he hid in his basement at home. He didn’t come out for a long time, not until after dark. Nobody knew he did it.

When he was older, he was playing with matches in a dry field at Long Lake where his grandfather owned some property. He lit the grass, and then tried to stomp it out, but it quickly got away from him. He didn’t mean to do it, but fire always fascinated him.

That boy grew up in the fifties, seeming to be such a nonentity that no one beyond his small circle would ever know his name. It would be decades before his entire story was told through interrogations and interviews and a full-scale investigation the like of which had never been seen before. His every secret thought would be exposed, studied; each facet turned and held up to the light of day so that the mundane became horrendous, the salacious channeled to the deep perversion that it was.