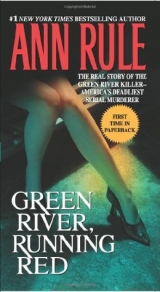

Текст книги "Green River, Running Red. The Real Story of the Green River Killer - America's Deadliest Serial Murderer"

Автор книги: Ann Rule

Жанр:

Маньяки

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

Dennis, who was home for Christmas vacation from college, remembered his sister then. It would be one of his final memories. For most of her pregnancy, she barely showed, but she was close to term in December and she was “very pregnant and awkward.” She had always been so slender, strong, and agile that it seemed strange to see her that way. He agreed with his parents and siblings that she was in no position to try to raise a newborn. Ray couldn’t be counted on.

In the end, Bridget probably made the right choice, the unselfish choice, for her baby. She knew she couldn’t take care of herself, much less a baby. She decided she would give it up for adoption.

On Christmas day, Bridget, her mother, and her brother, Dennis, went to Providence Hospital. Her family was with her as she gave birth to a baby boy, whom she named Steven. Dennis took pictures of Steven, and they memorized his face. They all loved the infant, but they had no other choice.

Ray’s father paid the hospital bill at Providence. For her own reasons, Bridget chose to tell her friends that her baby had died right after being born. On New Year’s Eve, Dave received a phone call and he recognized Bridget’s voice instantly, even though he heard only a bone-chilling wail that became a high-pitched shriek or maybe hysterical laughter. And then she hung up.

He would always believe that her call was a cry for help after her baby “died,” but he didn’t know where she was or how to reach her. Bridget was now at least two intermediaries removed from him, and he had heard she and the man she lived with were doing harder drugs.

In actual fact, Bridget didn’t do drugs during her pregnancy, and it’s possible that she never used again. But she felt so empty after Steven was given up for adoption, and said she was going to move back with Ray despite all the discussions she had with her mother. In an unusual reversal of stances, it was Bridget who said that she “needed a man in her life,” and her mother, caught up in the new philosophy of Women’s Lib, who argued that Bridget was smart and strong and didn’t need to settle for any man who came along. She didn’t need Ray or anyone else. She had earned her GED and she could go to college and be whoever she wanted to be.

But Bridget waffled, even though she stayed in her parents’ home until the end of January 1982, and they hoped that maybe she would remain with them until she really got on her feet. Tragically, she moved back with Ray in early February, and they continued their migrating lifestyle—from motel to motel.

All of them missed the baby, even though they knew they had made the right decision. Dennis Meehan was reading a Seattle paper ten days after Steven was born and he came across an article about a foster family who had taken in dozens of children, even adopting children who were disabled. The mom held a baby in her lap, and he recognized Steven, who looked happy and healthy and safe.

Dennis called his mother over and showed her the article, saying, “Look, Steven’s on his way—he’s okay!”

Bridget conceived again within a month to six weeks. Again, it was Ray’s baby, and, again, she was living a lifestyle where she couldn’t care for a child. Still, she called home regularly.

Bridget and Ray moved to Chehalis, Washington—eighty-two miles south of Seattle—to stay with a friend of Ray’s. Ray himself had no visible means of support.

In May 1982, Mary Bridget Meehan turned eighteen. She was legally an adult, but she was still lost, no matter how many hands were held out trying to rescue her, and she carried within her another life that would need love and care. She visited a clinic in Chehalis for a pregnancy test on June 8, 1982. According to the doctor there, her baby was due on November 27. She never returned to the clinic, although she did reach out to a battered women’s shelter, where she complained that Ray was hitting her again.

The couple moved back to Seattle, and Ray’s father, who owned a nightclub, paid for their lodging frequently. Once again Bridget was very pregnant and Ray’s father worried about her. She and Ray stayed at a motel on the highway and then at the Economy Inn, and finally at the Western Six. In some ways, she was the same Mary Bridget that she’d been as a little girl. She smuggled three cats and a dog into their room, hoping the manager wouldn’t find out.

And now, in September, she had disappeared. Ray would not admit to Port of Seattle detective Jerry Alexander that Bridget was working as a prostitute, but Alexander found others who said she was. Sometimes she took her dog with her, walking along the highway near Larry’s Market, the gourmet supermarket. On the day she disappeared, Bridget had brought the dog back to the motel room she shared with Ray and left again. Ray said he had been working on the old car that belonged to Bridget, and he’d had his head in the engine compartment when she called “Good-bye” to him.

Where she had gone after she walked away from the Western Six Motel, nobody knew. When Ray reported Bridget missing, even he was confused about how pregnant she was; he thought it was either seven or eight months. The task force detectives doubted many of his answers. They learned from people who knew the couple that he often tried to persuade his friends to “get a girl to work the streets for you, too.”

“Bridget seemed too sweet and too intelligent to get talked into that,” one man told Jerry Alexander, “but I can’t say for sure.”

Her brother Dennis had difficulty believing that she would have been involved in prostitution so far into her pregnancy, but he could visualize her accepting a ride from a stranger. She liked to put on a tough veneer, but she still had her basic trust in the goodness of people.

It was herself that she didn’t really like.

Those who loved Bridget searched for her, but they didn’t find anyone who had seen her after that last day: September 15, 1982. Nor did the task force. Ray moved out of the motel, leaving Bridget’s cats behind. Animal Control picked them up. Ray threw away Bridget’s drawings and possessions, and stopped calling her parents. He found another girlfriend.

WHEN DAVE, Bridget’s long-ago soul mate, was forty, he had a dream about her, an intense dream. In the dream, he and Alison, who had been with him for years, were living in a nice little farmhouse somewhere and Bridget and a guy who seemed “okay” came to visit at the farm and they had a nine-year-old boy and a dog with them.

“We all visited and it was very pleasant, and then they had to leave. I walked them out a long drive, but something went wrong between me and her friend and we started yelling at each other. At the end of the dream, she had gotten the child out of there, and it was just me and him. I was going to go back in the house and get a gun—very strange because I’ve never owned one. I was very upset when the dream ended.”

Awake, he had the unshakable impression that the woman in the dream really was Bridget and he was being visited by the part of her that still lived. She looked as she would have looked twenty years later.

“I found myself thinking that I really needed to call her and ask how she’d been…and then I remembered.”

Dave still felt Bridget’s presence and wondered how to tap into that. He turned on his computer and typed “Bridget Meehan Green River” into the search engine.

There were, of course, several articles that popped up. He had never known exactly when Bridget vanished or when she had died—if, indeed, she had. He looked absently at the date and realized that this early morning was exactly twenty years since Bridget walked down the highway into some dark oblivion.

“I actually got scared. I knew I wanted to talk to somebody about Bridget. I don’t think I’ll ever get over it.”

7

THE KING COUNTY public’s reaction to a yet unknown number of murdered “prostitutes” reflected views that ranged from disapproval and distaste to sympathy and sorrow. Rigidly judgmental editorials popped up in a number of small-town papers in the south end of the county. Essentially, the writers blamed the victims for being out on the street and taking such foolish chances. Beyond that, they accused lawmakers of being lax in controlling sex for sale. Interestingly, nobody blamed the johns who patronized the young women in short skirts, high heels, and, now that the weather was cooling, little rabbit-fur jackets. It seemed somehow more politically correct to condemn the dead girls themselves.

I LIVED in Des Moines, a little town where the victims were both disappearing and being found, and I passed too many young women who stood on the fog lines along the Pacific Highway. “Fog line” is a literal term; by late September in the Northwest, there is a great need for reflective strips along the side of the road because the wet black asphalt disappears into the thick mist that falls after sunset.

Sometimes over the years ahead, I would pull over and attempt to talk with the very young girls, trying to warn them of the danger all around the Strip. A couple of girls nodded and said, “We know, but we’re being careful. We use the buddy system and we take down license numbers.” Others said they didn’t care, that only dumb amateurs got caught. One or two stared at me coldly as if to say “Mind your own business.”

I had known any number of working girls in my life. I met dozens of them when I was a student intern at Hillcrest. There were absolutely beautiful girls as well as sad, homely girls there. A few years after that summer I spent “in reform school,” I ran into one of my Hillcrest girls in the bus station in Portland. She hugged me as if we were sorority sisters, and told me she had gone back to “the life.” Irene was still gorgeous and assured me she was doing well and making a lot of money. She had an older “boyfriend” who had set her up in an apartment.

Another Hillcrest alumna was a resident in the Seattle city jail while I was a policewoman, and she shouted my name as I booked in another prisoner. Janice asked me how much I was making, and I told her “Four hundred a month.” She grinned and said, “You could make more than four hundred a week if you did what I do.”

“But you’re in jail,” I said, “and I’m free.”

She shrugged and smiled wider.

It wasn’t just being free, and we both knew it. They were all living through bad times, no matter how much they protested. I think the saddest was the girl I had to arrest because a senior policewoman spotted her going into a hotel with a sailor and ordered me to follow her. I didn’t want to, because it didn’t seem fair; why should we arrest her and not him, too? The young woman limped badly and she was very pregnant. By the time we reached the room and the manager slipped his key in the lock, the sexual act, whatever it had been, was over. The “scarlet woman” was sitting in bed, eating a hamburger. She had sold herself because she was hungry. But she had broken the law, and while tears ran down her face, I took her down to be booked into jail.

I have never forgotten her.

On the opposite end of the spectrum was a woman in her late thirties who used the name “Jolly K.” Jolly K. had transcended a decade or more of prostitution to establish a nationwide support group for parents who battered their children. A striking woman with auburn hair and impeccable grooming, she had become highly respected when I interviewed her for a magazine article in the seventies.

“Weren’t you ever afraid to be alone with men that you didn’t know?” I asked her, after she explained that she usually met her johns in the cocktail lounges of hotels.

She shook her head, “No, I could tell if they were safe after talking to them for five minutes or so. I was only beaten up twice…”

Only twice.

DICK KRASKE’S detectives expanded their efforts and covered more and more ground as they followed up both tips and witnesses’ statements. Each missing girl had family, friends, and associates, and even if talking to them led nowhere, there was always the chance that it might.

Dick Kraske noted that there was a positive side to the investigation, as frustrating as it was. Police and those involved in prostitution are not really natural enemies, but they view each other warily. “Usually, our people are out there trying to arrest them,” Kraske commented. “The women have their own communication system, and that’s where a lot of our information is coming from. We have been getting more help—quite a bit more—from the prostitutes than from the pimps. Some of them are very credible, and they’re very concerned.

“They talk to each other. ‘That guy is kinky. That one is weird. I saw a gun in the pocket of the guy’s car. Stay away from him.’ They know and recognize the weirdos.”

Now the prostitutes were running scared, and as widely diverse as their mutual goals were, the frightened women and the frustrated cops were cooperating with one another.

There were a lot of weirdos out there. Some of the earliest theories speculated that it might be significant that the SeaTac International Airport was right in the middle of the “kill zone.” Could the killer be someone who flew in and out of Seattle? Perhaps a businessman—or even a pilot. Exploring that premise, Kraske said that his task force had issued bulletins asking for information about prostitutes who might have been murdered near other major airports in the country. If a frequent flyer was killing girls in Seattle, wouldn’t it make sense that he was doing the same thing near other airports?

It was a good idea, but Kraske said, “We didn’t get anything back on that at all. So we still feel it is probably someone in this state.”

Officially, there were still only six victims.

AS SEPTEMBER turned into October, there was an obvious decline in the number of young women strolling the Pacific Highway. A lot of them were frightened, particularly when their network said that there were more missing girls than the police were talking about. It wasn’t just the Green River, which seemed distant from the SeaTac Strip to many of the girls; Giselle Lovvorn had been found murdered only a block or so off the Strip.

AND THEN acquaintances of two more teenagers realized that they hadn’t seen the girls in their usual haunts for quite a while. One was sixteen-year-old, five-feet-seven, 125-pound Terry Rene Milligan. She had been living with her boyfriend in a motel on Pacific Highway near S. 144th Street. He reported her missing and then promptly disappeared before detectives could ask him questions. The motel manager where Terry lived said the last time she’d seen her she was arguing with another girl, allegedly over a pimp, but the witness couldn’t describe the man or the other girl. Four of the dead and missing women were white, and four, including Terry, were black.

Terry shouldn’t have been out on the highway; she’d had so much going for her. She had been a brilliant student, and had dreams of going to Yale and studying computer science. She’d been active in her church, too, but when she became pregnant while she was still in middle school, her dreams got sidetracked. She adored her baby boy, but she dropped out of school and never went back.

Pierce Brooks had listed characteristics he deduced about serial killers as he urged police all over America to recognize the danger. One of his findings was that serial killers murdered intraracially—that is, whites killed whites, and blacks killed blacks. There weren’t enough Asian or Indian serial killers to gather statistics. Oddly, the Green River Killer didn’t seem to have any preference about the race of his victims. No one knew yet what race he was, but his preferred victims so far were young, vulnerable women he apparently encountered on the highway. He hadn’t broken into homes to rape or murder women in the SeaTac area.

But he had been more active in a shorter time in taking victims than any killer in the Northwest to date, including Bundy. The investigators learned that another girl had vanished only one day before Terry Milligan went missing. Kase Ann Lee, who happened to be white, was gone. She was sixteen, too, but the only picture available of her made her look thirty-five. Kase had once lived in the same motel as Terry Milligan, but that might be only a tenuous connection. Certain hotels and motels clustered around the airport were temporary homes to many young prostitutes.

Kase’s husband told police she was gone from the $300-a-month apartment they shared at S. 30th and 208th South. Both Terry’s and Kase’s addresses were right in the circle where the Green River Killer prowled.

KASE LEE was a pretty little thing, although her eyes looked old and tired in the photograph the task force had. She had strawberry blond hair and blue eyes, and weighed only 105 pounds. Even as defenseless as she was, somebody had been mis-treating her. Members of her loosely knit circle of friends told detectives that she often had cuts and bruises on her face as if she had been badly beaten. She wouldn’t tell them who had done this to her.

Two weeks earlier, police had been called to the motel where she lived in response to a fight, which did not involve Kase, and that alarmed many of the residents, most of whom avoided direct contact with law enforcement whenever possible. The task force detectives got all the information they could in their first contact, knowing that most of the witnesses would have moved on when they came back. They were right; strangers occupied the motel rooms when they returned.

Both Kase’s husband and Terry’s boyfriend were quickly eliminated as viable suspects. It could have been anyone the teenagers had met along the SeaTac Strip, some faceless wraith who killed them and then disappeared into the fog.

Since Mary Bridget Meehan, Terry Milligan, and Kase Lee hadn’t been found, they were not officially listed as Green River victims. There was always the chance they were alive and well in some other city.

Their families could only hope that was true.

8

THE OFFICIAL GREEN RIVER toll remained at six, as investigators Dave Reichert and Bob LaMoria continued to seek out witnesses or suspects. One suspect, however, planted himself firmly in the focus of their attention. Far from avoiding detectives, an unemployed cabdriver named Melvyn Wayne Foster was anxious for the media to know that he was central to the Green River investigation. Foster, forty-three, had a rather bland face with a high-domed forehead, and he wore metal-rimmed glasses. He looked more like an accountant or a law clerk out of the thirties than a cabdriver. But he liked to present himself as a tough guy who wasn’t afraid of a fight.

And he knew the SeaTac Strip very well, just as Dick Kraske knew Foster very well. “I was a brand-new cop back in the early sixties,” Kraske remembered. “I worked in the I.D. Bureau in the old jail, and as ‘the new guy,’ I was assigned to fingerprint all the new prisoners at the mug location on C Deck. Mel was on the list that day, en route to the State Reformatory at Monroe for auto theft.”

Kraske forgot all about Mel Foster until September 9, 1982, when Foster strolled into the Criminal Investigation Division with an offer to provide information on some of the Green River victims.

“I assigned Reichert and LaMoria to talk with him while I checked Records to search for Mel’s name,” Kraske said. “I pulled up his fingerprint card, taken when he was nineteen years old, and my signature was on it.”

Melvyn Foster appeared to be consumed with interest in the missing and murdered girls. He even offered the detectives his psychological theories on what the killer might be thinking. When he was asked where he got his experience as a psychologist, he said he’d “taken a couple of courses in prison.”

Foster’s prison records indicated that he had tested above average in intelligence while he was incarcerated, but he certainly wasn’t a trained psychologist. Still, he claimed to have assisted other law enforcement agencies as an “unpaid intelligence operative.” He gave Dave Reichert and Bob LaMoria the names of two cabdrivers he considered likely suspects.

The young detectives looked at Foster with interest, although their faces didn’t betray what they were thinking. Any astute detective knows that killers often like to be part of the probe into the murders they have committed, just as arsonists are drawn to the crowds that gather at the fires they have started.

IN HIS CAREFULLY DRAWN OVERVIEW of similarities in the characteristics of serial killers, Pierce Brooks had already noted that many of them tend to be “police groupies,” and his supposition would be validated over the years: Wayne Williams, the Atlanta Child Murderer; the Hillside Stranglers in Los Angeles in 1978—Kenneth Bianchi and his adopted cousin Angelo Buono—who killed both prostitutes and schoolgirls to feed their own sadistic fantasies; Edmund Kemper in San Jose, who murdered his grandparents, his mother, her best friend, and coeds; and Ted Bundy all enjoyed their games with the police, perhaps as much as their killing games. Some had gone so far as to apply for jobs in law enforcement. Apparently jousting with detectives was a way of extending their pride over killing and evading detection.

Serial killers, once imprisoned, often correspond with one another, comparing tolls of human misery and competing for an awful kind of championship. Was Melvyn Foster aiming for a spot on the hierarchy of serial murder?

He had no hope of becoming a detective, except in his own mind. He had two convictions related to auto theft and he’d served almost nine years in prison. However, he seemed to harbor no animosity toward police, and glowed with pride as he said he had come forward to assist the task force with his knowledge. He told them he was quite sure he had known five of the victims.

“How is that?” they asked.

“I like to hang around with street kids,” he said. “They’re out there on their own with nobody much to help them.”

Foster painted himself as a kind of unofficial social worker who came to the aid of runaways and teenagers when they were in trouble. He laughed when he told reporters later that he had gotten acquainted with prostitutes because “I took my coffee breaks in the wrong restaurant.”

Melvyn Foster’s interest in the young women who had gravitated to the highway wasn’t entirely altruistic. He admitted that he had also received sexual favors from some of the girls “as a way of settling the books” when they couldn’t pay their cab fares, but he stressed that he was basically a benevolent influence in their lives.

Not surprisingly, Foster fit neatly within the parameters of the kind of killer the task force was seeking. Reichert, who was ten years younger than Foster, wasn’t nearly as streetwise as the experienced con man, and tended to see him as a prime suspect rather than as a man who craved notoriety.

Reichert and Bob LaMoria questioned Foster extensively, and he did, indeed, become more and more interesting. First, he’d mentioned knowing some of the victims, and then he denied it, saying they must have misunderstood. When he submitted to a polygraph test on September 20, 1982, he flunked. Now he waffled, saying that he might have known them, but that he sometimes had trouble putting names and faces together.

The two cabdrivers whose names Foster had given to the detectives also took lie detector tests. They passed. Foster backpedaled, trying to explain why his answers appeared deceptive: “I believe I have a nervous problem that causes me to flunk lie detector tests.”

After the disappointment when Debra Bonner’s and Giselle Lovvorn’s boyfriends were cleared, it seemed that the investigators might have found the right man. Foster looked good. He knew the SeaTac Strip, had known at least some of the victims, flunked his polygraph, and was a little too fascinated with the investigation—all indicators that kept the task force detectives’ eyes on him.

IN THE EARLY FALL, the task force had only one other viable suspect: John Norris Hanks, thirty-five, who had been convicted of murdering his first wife’s older sister, stabbing her sixteen times. But that was only the beginning. He had served his time in Soledad Prison and was presently in jail in California on assault charges. San Francisco detectives said he was the prime suspect in six of their unsolved murders from the midseventies—all women who had been strangled.

Hanks, a computer technician, had come to the forefront of the Green River investigation when he was arrested in East Palo Alto on a warrant charging him with assaulting his wife in Seattle. They had been married less than a month when, on September 9, she reported him to Seattle police officers after he had bound her ankles together and then choked her unconscious in their downtown Seattle apartment.

He was smart and he’d been a perfect prisoner, but something in Hanks hated women and he had attacked both relatives and strangers. “Wherever he is,” a San Francisco police inspector commented, “women seem to end up getting killed.”

And John Norris Hanks had been in Seattle in early July 1982—about the time the first Green River victims disappeared. On July 8, he’d rented a car at the SeaTac Airport, charging it to the company he worked for. He never returned it; the 1982 silver Camaro was found abandoned in the airport parking lot on September 23.

King County detectives could not ignore a suspect who seemed to have a fetish for strangling women and had been in the SeaTac Airport area in the time frame of the Green River body discoveries. They traveled to San Francisco to question him, but he appeared to have a sound alibi—at least for the Seattle-area murders. People had seen him in San Francisco during the vital time period. Gradually, Hanks faded as a workable suspect in Washington State. He was sentenced to four years in prison for the assault on his bride.

THAT LEFT MELVYN FOSTER in the top spot, although he apparently didn’t realize that could be dangerous to him. Still confident, Foster gave task force detectives his verbal permission to search the house in Lacey, Washington, where he lived with his father. The small, shake-sided house was fifty miles south of the SeaTac Strip. It had several sheds and outbuildings. All of the rooms were filled with furniture or tools or “stuff” of one kind or another, the possessions of an old man who had lived there for many years, along with all of Melvyn Foster’s belongings.

It made a very long day for the searchers looking for something that might link Foster to the murdered girls. It was probably an even longer day for the man who had drawn their attention to himself. Melvyn Foster became annoyed as the hours passed and he watched the detectives and deputies poking through his father’s house. He had apparently expected them to take a cursory look and go away.

Foster went public on October 5, 1982, announcing that he was a suspect. He invited reporters to watch the sheriff’s deputies and detectives who were watching him. “All they found were some swinging singles magazines I received unsolicited in the mail, and a bra one of my ex-wives left behind in a closet,” he told reporters afterward, with a tinge of outrage in his voice. That didn’t make him a killer.

Speaking almost daily with television reporters, Foster was a shoo-in for a spot on the nightly news. But now he offered reasons as to why he couldn’t possibly be the Green River Killer. He pointed out that his car wasn’t drivable in mid-July and he wasn’t currently strong enough to strangle a young girl who was struggling, much less pick her body up and throw her over a riverbank; he’d been limping since March because of torn cartilage in his knee.

With reporters jotting down his words, Foster became more garrulous and confidential. He explained how he suffered from a rare kind of “nervous autonomic tic” that always showed up on lie detector tests even when he was telling the truth.

Foster said he had not been lucky romantically. He’d been married and divorced five times, but he said he hadn’t given up on finding love. He was thirty when he married for the first time, but it lasted only 121 days because his bride “just couldn’t stand domesticity and she just up and quietly disappeared.” He married the next year and that one lasted long enough for them to have two sons. Four years later, he divorced his second wife when she became clinically depressed and was admitted to a mental hospital. After moving back in with Melvyn and their sons, she subsequently died of an overdose of lithium.

“We had a very special thing going for seven years,” he commented. “I miss her every day.”

His third wife was a rebound affair and lasted less than six months. He said he’d divorced her when she slapped his two-year-old son. “That one ended on the spot,” he said firmly.

The fourth union was even shorter—only six weeks, another rebound. Foster had taken his boys to California by then, and he said he had his paramedic’s license. He met his fifth wife in Anaheim, and she was already pregnant when he met her.

His last wife had divorced him because she claimed he’d hurt her five-week-old baby deliberately. Foster explained what really happened. The baby had suddenly stopped breathing, and “being a trained medic, I picked her up to resuscitate her. When I grabbed her, my right hand was a little stronger than it should have been, and it inflicted six in-line fractures on her rib cage.”

Foster said that the pediatrician at a dependency hearing had testified in his favor, but the infant was taken away from both his wife and him. (The doctor, when contacted, disagreed, saying, “She was taken away because of some injuries that shouldn’t have happened to a baby that young. The injuries were never fully explained, and the whole situation at home was not good.”)

Between that loss and Foster’s work as a cabbie and friend to street people in Seattle, his last marriage had collapsed, too. The divorce was final in June 1982, but by that time he was already engaged to Kelly, a seventeen-year-old runaway from Port Angeles, Washington.