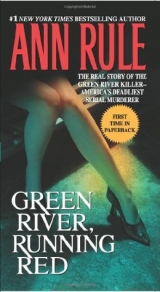

Текст книги "Green River, Running Red. The Real Story of the Green River Killer - America's Deadliest Serial Murderer"

Автор книги: Ann Rule

Жанр:

Маньяки

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

The one thing that was certain, and that had been certain since Dr. Edmond Locard of Lyon, France, directed the very first crime lab in the world, was his Exchange Principle. Formulated in the early years of the twentieth century, Locard’s theory became the basis for any investigation of any crime scene: Each criminal leaves something of himself at a crime scene, no matter how minute, and takes something of the crime scene away with him, even if it is infinitesimal. Every new generation of detectives—and television shows like CSI—works on Locard’s principle. But each decade brings with it more sophisticated tools to help the detectives find the minutiae that solves crimes.

As the Green River investigation moved through the eighties, there would be many advances in forensic science. The earliest, however, required a good portion of each substance to be tested—hair, blood, semen, chemicals, paint, and so on—because the various lab processes would destroy the samples submitted.

Even so, the second Green River Task Force was extremely optimistic in early 1984. Deluged with tips from the public, from prostitutes and street people, and from psychics, they investigated and cataloged all of them. However, they had to have a system to establish priority.

“We had ‘A,’ ‘B,’ and ‘C’ categories,” Adamson explained. “A’s had to be looked at as soon as possible, and they had to be eliminated conclusively before we moved on. B’s were people who might be good suspects, and we certainly needed to look at them, but we could take more time to get to them. C’s might possibly be suspects, but, with them, we didn’t have a lot to go on and we felt it wasn’t really important to get to them in the near future.”

One of the problems Adamson tried to monitor was the natural tendency of detectives to fixate on one suspect, and one suspect only. Homicide detectives are human like anyone else and they aren’t infallible, although their job requires that they produce irrefutable evidence that a prosecutor can present to a jury.

“I kept telling my staff that we had to remember not to get myopic,” Adamson said. “When a detective became too focused on a single suspect, I reminded him—or her—that all of us got ‘obsessed’ with certain people. One of us might be right, but all of us couldn’t be right.”

Dave Reichert was still convinced that Melvyn Foster was the Green River Killer. Another detective was positive the killer was a Kent attorney whose clientele included a disproportionate number of women in the “vice trade.” The lawyer lived very close to where the first five bodies had been left in the river, and this suspect had once spent time in a California town where there were several unsolved murders of women.

“I’d see that attorney, who was in his forties, occasionally,” Adamson said. “He was always immaculately dressed—not a hair out of place. I thought to myself, ‘No way is this guy gonna get in any river, get wet and dirty, and then show up in court.’ I’d been down to the river in my dress shoes, and a month later, you could still see the grime on them, and I didn’t get into the water. The real killer would have had to wade in there in the silt and mud.”

The suspicious-acting attorney was later murdered by a disgruntled tenant in one of the shabby apartment houses he owned.

All of the investigators felt deeply, and it was tough for them to let go of their beliefs. There were just too many truly bizarre people who came to their attention. Even Adamson would soon have his own “favorite” suspect, just as they all did. Rather, he would have three preferred suspects. Some of the public didn’t care who the Green River Killer was. They demanded only an early arrest.

Most of the time, all majors and above in the sheriff’s office were too busy with administrative duties to actually go out in the field, but each was required to perform “Command Duty” every few months. “I’d go out and check in with various precincts, respond to what was going on out in the county. And I used these times to drive by three guys’ places,” Adamson said. He wasn’t sure what he might see, and he really didn’t think he was going to be lucky enough to find them doing something incriminating just as he drove by, but he felt compelled to check on them.

One of Adamson’s prime suspects was an older man a young prostitute had reported as a very peculiar “client.” She had agreed to meet the man at a motel on the highway, and he was quite a bit older than the usual johns. He’d seemed nice enough at first. He’d even taken her to the House of Values and told her she could buy whatever clothes she wanted. Then he took her to his house, which was close to the Green River. He owned a good-size property with many acres of land and a barn.

But once the man—Ingmar Rasmussen*—took the girl into his house, he refused to take her back to the highway. He kept her there for a week, showing her a special police badge. She didn’t know whether to believe him or not. He proudly showed her his barn. With a sinking feeling, she saw that one area of the walls was plastered with pictures of women. He took pictures of her, too. She wondered if they were going to end up on the wall. Worse, she wondered where she might end up.

Rasmussen obviously was well off, and he didn’t really hurt her, but she felt trapped because she was his prisoner. Finally, he took her back to the motel where she had met him. When she told detectives about the rich man with the barn full of female photographs, it sounded as if she had only an overactive imagination. However, she was able to lead the detectives back to Rasmussen’s spread of land and point out the big house and barn set in the Green River valley.

In a ruse to take a look inside, Captain Bob Evans once drove alone to Rasmussen’s place in an unmarked white Cadillac. He knocked on the door and when Rasmussen opened it, Evans said his car had broken down. The wealthy farmer was arrested on charges of suspicion of unlawful confinement and a search warrant was obtained for his property.

The task force investigators saw that there was a round door in the barn ceiling, held in place with big spikes. They swarmed over the barn, wondering what arcane discoveries they might make. But they were to be disappointed. “We didn’t find any pictures there,” Adamson said, “although we did find one of Rasmussen’s cameras, and when the film was developed, our informant’s pictures were there.”

If this had been a horror movie, Ingmar Rasmussen’s isolated barn would have been the ideal place for a serial killer to hide his victims. But this was the real world, and he, like so many others, was removed from the suspect list.

He was a little kinky, all right, and he had taken young prostitutes to his barn for photo sessions. A private investigator a worried Rasmussen had hired told Adamson that the pictures had been in the barn all along, even during their search, but the old man had taken them down from the barn wall and put them in a drawer.

“We’d gotten very good at outdoor crime scenes,” Adamson said wryly, “but we were rusty on working indoor scenes, and we’d missed the photos.”

25

WHILE THE CONSERVATIVE CITIZENS of south King County tended to blame the business of prostitution and vice for the shadow over their lives, they didn’t really care to become involved. Responding to their complaints, King County executive Randy Revelle called a meeting in the Tukwila City Hall. Ironically, although Revelle, Sheriff Vern Thomas, and Captain Frank Adamson showed up to answer questions and listen to concerns, only four townspeople attended. The leaders of the probe and a gaggle of reporters were present, but nobody else seemed to care.

One person asked if the sheriff’s office thought the killer would strike again, and Frank Adamson answered an unequivocal “Yes.”

The Green River Killer had no reason to stop killing. As far as the detectives knew, he hadn’t even come close to being caught, and he must, indeed, be enjoying his “success.” Historically, serial killers don’t stop—they accelerate. Unless such murderers are arrested and incarcerated for other crimes or they become physically unable to stalk victims or they die, they keep going. In the rare case, a radical life change—marriage or divorce or severe illness—can call a halt to their obsession to destroy lives.

So, of course, the man they were looking for was going to kill again. And they were afraid it was going to be soon. They were right.

MARY EXZETTA WEST vanished from the Rainier Valley neighborhood on February 6, 1984. She had a sweet face and a shy smile. She lived with her aunt and she was always thoughtful about coming home on time. She had left her aunt’s house at midmorning that Monday. In exactly a month, Mary would have turned seventeen, but she didn’t make it that far. In six months, she would have given birth to a baby, but very few people knew that she was pregnant. She didn’t know what she was going to do when she began to show.

It was odd that so many of the GRK’s victims were killed so close to their birthdays. He couldn’t have known when they were born, not if he was picking them up as they happened to cross his path when he was in his killing mode. It had to be only grim coincidence.

IT HAD BEEN twenty months and the victim toll kept rising. Many people were anxious and restless, including the man himself, although the men and women who were looking for him didn’t know that. Women’s Libbers were stridently blaming the Green River Task Force and law enforcement in general for failing to really try to protect them by not catching the Green River Killer.

The GRK was not strident at all; he merely wanted to up the ante a little and make the tournament of terror more interesting.

On February 20, Post-Intelligencer reporter Mike Barber, who had written extensively about the Green River cases, had a letter routed to him from the City Desk. It had arrived in a small, plain white envelope with a Seattle postmark.

The typewritten address was incorrect:

Seattle postintelligencer

fairview n john

PO Box 70

Seattle WA 98111

Actually, the street address belonged to the Seattle Times, but somehow the letter got to the P.I. The sender had added “very inportent” to the envelope.

Barber read the message inside, which had no spaces at all between the words, and at first, it seemed incomprehensible. He looked at it several times to see what the “code” might be, if, indeed, there was a code. And it still made little sense.

Gradually, he began to draw diagonal lines between what might be words and the information became clearer, although the writer was either uneducated or striving to appear so.

whatyou eedtonoaboutthegreenriverman

dontthrowway

I first onebokenordislocatarmwhy

2oneblackinriverhadastoneinthevaginawhy

3whysomeinriversomeabovegroundsomeunderground

4insurancewhogotit

5whosetogainbytheredeaths

6truckdisoutofstatefatherhadpaintedorinriver

7somehadfingeralscutoff

8hehadsexaftertheydeadhesmokes

9hechewsgum

10chancefirstoneblackmaledhim

11youworkmeornobody

12thinkchangedhismo

bussnessmanorsellman

13carandmotelreservation

14manseenbiglugageoutofmotelwasheavyneededhelp

keysidcardatroad18whos

15wheresolosesomeringandmisc

16outofstatecop

17don’tkillinnoonarealookinoutside

18onehadoldscarse

19momaplehadredwinelombroscsomefishanddumpedthere

20anydurgsorselling

21headfoundwhofountitwhereisrest

22whendietheydiedayornight

23whatourntheremouthsoreisitatrick

24whytakesomeclothesandleavereast

25thekillerwheresatleastonering

26realestmanisoneman

27longhaultruckdriverlastseenwithone

28somehadropemarksonneckar.dhands

29oneblackinriverhaddoraononly

30alstrangledbutwithdefermetheds

31oneblackinriverhadworkedformetro

32mosthadpimpsbettingthem

33escortmodelingforcedthemofffearofdeth

34maybepimphatergetbackatthem

34whofindstheboneswhatareththerefor

35manwhithgunorknife

36someonepaidtokilloneothersarethideit

37killwhotheyareorisitwhattheyare

38anydeaddiferthenrestt

39itcouldamanportladsomeworkedthere

40ehatkindofmanisthis

therewasabookliftatdenneysignotthisotof

itbilongstocop

The letter was signed: “callmefred.”

“Call me Fred.” Well, that was clear enough, although it was unlikely that the tipster was really named Fred. The letter had probably been written by someone who wanted to play detective. He was offering motives that anyone might think of, but he was also giving a lot of information that wasn’t generally known. After Barber finished trying to separate the words into some kind of sense, he turned the letter over to Dave Reichert.

At the request of Bruce Kalin, a task force evidence specialist, Tonya Yzaguerre, a latent print examiner for the sheriff’s office, examined it for fingerprints. Using the Ninhydrin process—which uses chemicals and heat and can bring up prints left even decades before—Yzaguerre found one that would be saved in the hope that someday they would glean prints from a Green River crime scene or body site. And then she sent the letter on to the F.B.I., both for John Douglas to evaluate for its content and in the hope that the typewriter used might be identified.

The F.B.I. lab felt that the typewriter was probably an Olympia style with a horizontal spacing of 2.60mm per character, and it had a fabric ribbon.

Despite the fact that the letter writer had referred to heretofore unpublished information like “One black in river had a stone in the vagina. Why?” and “Mom maple had red wine lombrosco some fish and dumped there,” John Douglas wrote to Bruce Kalin that he didn’t feel the real Green River Killer had written the letter.

“It is my opinion that the author of the written communiqué has no connection with the Green River Homicides. The communiqué reflects a subject who is average in intelligence and one who is making a feeble and amateurish attempt to gain some personal importance by manipulating the investigation. If this subject has made statements relative to the investigation which were not already released to the press, he would have to have access to this information [via] Task Force.”

As for calls that had come in telling the task force where bodies might be found, Douglas was also skeptical. “Your caller is not specific enough to establish himself as the ‘Green River Murderer.’ However, he does have the capacity to imitate and be a ‘copycat’ killer.”

Douglas said that the Behavioral Science Unit of the F.B.I. had found that very few serial killers of this type had communicated with the media or an investigative team. When true serial killers had called, they gave very specific details to establish their credibility. “That is part of their personal need,” he pointed out. “Having feelings of inadequacies and lacking self-worth, they must feel powerful and important.”

Douglas advised the task force detectives to demand that the man who called them give more precise directions to any alleged body site. Then they were to deliberately stay away from that location. “This will anger him and demonstrate that you are stupid and ignorant and cannot follow simple instructions. [He] will be compelled to telephonically admonish you and/or oversee your investigation at the ‘wrong’ crime scene location.”

Douglas still doubted that either the letter writer or the phone tipster were the real GRK. But there was the threat of a deadly copycat.

That was all the Adamson task force needed. Another serial killer. The real question was how many people not on the task force itself knew about the triangular stones placed in the vaginas of some of the first victims, and also about the wine bottle—indeed, Lambrusco—and the fish left on Carol Christensen’s body? I knew, but I never told anyone what someone on the task force had told me. Some Seattle Times reporters found out, too, but they did not publish it. These pieces of information were definitely not generally known, and they hadn’t been mentioned in newspapers or on television.

It was almost impossible to tell if the letter Mike Barber received was the real thing. In retrospect, I believe it was. But there were so many tips coming in—to the Green River Task Force, to well-recognized journalists, and, yes, to me.

In 2003, as I went through the huge stacks of material I’d saved for twenty-two years, I came across an envelope virtually identical to the one Barber got. It is addressed to

Mrs Ann RULE

c/o POST-Intelligencer

6th & Wall

Seattle, Wasjington

98121

With a Seattle postmark of April 24, 1984, it had been sent two months after the first letter. This address for the P.I. was correct. The mistake in the spelling of Wasjington had been corrected with a pen. On the back flap, it said,

“Andy Stack”

GREEN RIVER

and in ink:

G-R (209)

Someone at the P.I. had scribbled my box number on it and forwarded it. There is nothing inside the envelope now, and I cannot say for sure that there ever was by the time I got it. I don’t know who wrote “Andy Stack” on the back of the envelope, but that was the pen name that I used for almost fifteen years when I wrote for True Detective and her four sister true-crime magazines. Very few people knew that at the time. The “209”? I have no idea who wrote that or what it meant. Was it the 209th tip the P.I. had received? Or did it mean something to the person who mailed it?

The mystery envelope was sent at a time when I was receiving so much information from readers and people interested in the Green River cases that I could barely keep up with it. As always, I passed on the most likely sounding information to the task force.

One thing I had not known was that there was someone who kept track of my public appearances, someone who often stood eight or ten feet away from me, watching. Over the years, I gave scores of lectures in the Seattle area, and people always asked about the Green River Killer. I often commented about my feeling that I must have sat in the next restaurant booth from him, or stood behind him in line at the supermarket. But that was only logical, deductive reasoning. Most of his victims had been abducted within a mile or so of where I lived, and many of their bodies had been found that close, too. All of us who lived in the south King County area had an eerie sense that we might know him, or, at least, that we must have seen him without realizing who he was.

In the mideighties, I was as confident as Frank Adamson and Dave Reichert were that it was merely a question of how many months it would take to make an arrest, and I often made predictions off the top of my head, assuring the audience that I believed he would be caught by Easter or Thanksgiving…or surely by the next Christmas.

And I believed it myself, never really thinking that the man who was so elusive might be sitting in a darkened auditorium, listening.

26

WHEN THE LETTER sent to Mike Barber was revealed, I took a crack at being a cryptographer. There is no question in my own mind that it was written by the real Green River Killer, obviously a man who knew many secret things but who had extremely limited grammar or spelling ability:

Translated by author:

What you need to know about the Green River man

Don’t throw away.

First one broken or dislocated arm. Why?

One black in river had a stone in the vagina. Why?

Why some in river? Some aboveground? Some underground?

Insurance. Who got it?

Who set [stood] to [gain] by their deaths?

Truck is out of state. Father had painted [it] or [it’s] in [the] river.

Some had fingernails cut off.

He had sex after they [were] dead. He smokes.

He chews gum.

[There is a] chance the first one blackmailed him.

You work [for] me or nobody.

[I] think he changed his M.O.

Businessman or salesman.

Car and motel reservation.

Man seen [carrying] big luggage out of motel. [It] was heavy [and he] needed help. Keys [and] I.D. card [are at] Road 18.

Where so close some ring and miscellaneous?

Out of state cop.

[I] don’t kill in no one area. Look in [and] outside.

One had old scars.

Mom [or one] Maple [Valley] had red wine Lombrosco, some fish dumped there.

Any drugs or selling?

Head found. Who found it? Where is the rest?

When did [they] die? Day or night?

What tore their mouths, or is it a trick?

Why take some clothes and leave [the] rest?

The Killer wears at least one ring.

Real estate man is one man.

Long haul truck driver last seen with one.

Some had rope marks on neck and hands.

One black in river had odor on only.

All strangled but with different methods.

One black in river had worked for Metro.

Most had pimps betting them.

Escort modeling forced them off fear of death.

Maybe pimp had—or got—back at them.

(Sic) Who finds the bones? What are they there for?

Man with gun or knife.

Someone paid to kill one. The others are [to] hide it.

Killed [because of] who they are. Or is it [because of] what they are?

Any dead different than [the] rest?

It could [be] a man [from] Portland. [Or] someone [who] worked there.

What kind of man is this?

There was a book left at Denney’s sign. Not this. Out of [doors.] It belongs to [a] cop.

Maybe the GRK wasn’t out there in my audiences very often. Maybe he actually resided a long way away. Although those of us in the south King County area still tended to believe that we lived in safe small towns—Des Moines, Riverton, Tukwila, Federal Way, Burien—our world had changed. In 1984, the SeaTac International Airport was known as the Jackson International Airport in honor of Senator Henry Jackson, and in the course of a year ten million people flew in and out of it. A quarter of a million people drove friends, families, and business associates to their flights or picked them up. If the Highline School District, which encompassed my children’s schools, were to incorporate as one city, it would be the fourth largest in the state of Washington.

Schuyler Ingle, a reporter for the Seattle Weekly with superior researching skills, looked at those figures and realized that 150,000 people passed through the Strip area in a month. Transients, yes, but from every class of society, both very rich and very poor and everything in between. They stayed in 4,500 motel rooms or slept wherever they could.

Lieutenant Jackson Beard headed the Pro-Active Team for the new task force. There were plainclothes officers on the Strip most nights. Female police officers dressed and made-up to look like prostitutes strolled beside the road at least one night a week. Male officers tried to keep an eye on them, waiting for the signal that a john had taken the bait. The Strip had become an uncomfortable place for both the real prostitutes and their customers, who would have to figure out a way to tell their wives and/or girlfriends why they’d been arrested.

Sooner or later, the task force detectives were sure they would catch the Green River Killer in their net. If he was still out there, he was going to approach the wrong woman. The Pro-Active Team’s decoys were concentrating far more on arresting and questioning the johns than the girls who made a meager living on the street.

But if they stopped the right john, how would they know it was him? They didn’t know that yet—unless he gave enough of himself away for them to get a search warrant for his house or his car. Unless he’d kept souvenirs of his victims, or photographs. Unless the science of DNA progressed to a point far beyond where it was in 1984.

He was out there. But as far as they knew, he wasn’t one of the dozens of men they arrested for propositioning the disguised police officers.

In mid-March 1984, he probably watched with some satisfaction as a group of women who called themselves the Women’s Coalition to Stop the Green River Murders mobilized. They planned to march to “take back the night,” and to point up their perception of the inadequacy of the Green River Task Force. They were joined by a San Francisco group called U.S. Prostitutes Collective.

“We are calling on all women to end the farce of the Green River murder investigation,” Melissa Adams of the coalition said in a news conference. “It is the responsibility of all of us to take action, and we must do it now—because women are dying.”

Men would not be allowed to march in the downtown Seattle parade that would begin at the Pike Place Market, proceed along First Avenue to University, up Third Avenue, and end at Prefontaine Square next to the King County Courthouse. However, they would be encouraged to watch and show support. The local chapter of the National Organization for Women and various domestic abuse and child abuse groups were supporting the coalition.

Two actual prostitutes were to be imported for the rally, one from San Francisco and one from London, women who would stand in for local working girls who were too frightened or embarrassed to be singled out for the crowd. It was two decades ago, and a different era. Women’s Libbers were often strident because they felt there was no other way. “The issue is the killing of women,” Adams said. “But we are showing unity with prostitutes who are the victims of this killer—and victims of a sexist society.

“Violence against women is an All-American sport.”

Perhaps it was. Certainly, even though the millennium has arrived, far too many women are still being sacrificed to domestic violence. But the coalition had chosen the wrong target, and it wasn’t the Green River Task Force, whose members yearned to catch the man who was killing young women far more, if possible, than the women who marched with banners that disparaged them. To have their overtime efforts and their near-pulverizing frustration called “a farce” was a bitter pill, although they had grown used to being undermined.

Dave Reichert, who had been with the task force continually for the longest time—almost two full years—probably felt the brunt of their derision the most. It was difficult to keep going when so many leads evaporated into nothing, where sure bets as suspects were cleared of any connection to the Green River cases and walked away.

“What we are finding out,” Reichert said, “is that police departments aren’t organized to handle a case like this. It’s not dealt with that often.”

That was true enough. But Seattle now had two almost back-to-back serial killing sieges. First, Ted Bundy—and now the Green River Killer. Frank Adamson’s task force reorganized, giving specific detectives responsibility for certain victims: Dave Reichert would be in charge of the investigations in the deaths of Wendy Coffield, Debra Bonner, Marcia Chapman, Cynthia Hinds, Opal Mills, and Leann Wilcox. Jim Doyon and Ben Colwell would work the cases of Carol Christensen, Kimi-Kai Pitsor, Yvonne Antosh, and the woman known only as Bones #2. Rich Battle and Paul Smith handled the murders of Giselle Lovvorn, Shawnda Summers, and Bones #8. Jerry Alexander and Ty Hughes traced the movements and people connected to Mary Bridget Meehan, Connie Naon, and Bones #6.

Those, of course, were only the victims whose remains had been found. Sergeant Bob Andrews, called “Grizzly” by his fellow detectives, would work missing persons with Randy Mullinax, Matt Haney, and Tom Jensen. Rupe Lettich would do follow-up on all homicide cases, but there was still a huge job left—the outpouring of tips and suspect names coming in willy-nilly from the public. Cheri Luxa, Rob Bardsley, Mike Hatch, and Bob LaMoria would try to field those and pass them on to the most likely investigators.

Until the day when, hopefully, a suspect would be identified, arrested, and convicted, the public would have no idea of how desperately hard they all worked, pounding pavements, making tens of thousands of phone calls, talking to people who told the truth, those who shaded the truth to suit themselves, and others who outright lied to them. It was akin to crocheting an elaborate tapestry as big as a football field, inserting each tiny stitch as new information began to match old intelligence.

All the while never knowing what centerpiece—whose face—was going to emerge in the middle of the tapestry.

THEY DID IT ALL without complaining and seemingly without letting their critics get under their skins. But sometimes the jeers got to be too much. Women shouting that the new Green River Task Force wasn’t even trying annoyed Lieutenant Danny Nolan because, if anyone knew how hard they were trying, it was Nolan. He had a poker face and a wry sense of humor.

But he didn’t find the Women’s Coalition humorous. Their sit-ins and marches interrupted the order of business for the task force, which already had enough problems. Cookie Hunt, a short, heavy-set woman who was blind in one eye, was one of the most stubborn critics. She organized an all-night sit-in outside task force headquarters, then housed in what had once been an elementary school. Cookie was so earnest in her crusade and so guileless that it was easier to feel sorry for her than to take offense. But she, too, was fighting the wrong target.

Nobody thought Cookie was a prostitute; she was just trying to help them. I used to offer her rides when I spotted her standing in the rain on the highway. She would grudgingly accept only because she knew I was friendly with the detectives and wrote positive things about them.

Frank Adamson worried about Cookie, too. He took criticism more philosophically than his crew did. On one windy, stormy, pounding-rain night, he couldn’t stand to watch the picketers walking in the cold rain. So he invited them in and told them they could demonstrate inside, and sleep in the hallway. They accepted. Some of the other task force detectives wondered how Danny Nolan was going to react to the sight of the “libbers” when he came to work in the morning.

“I’ll tell you how,” Adamson said with a grin. “He’ll walk in, take one look, and he won’t say a word. Watch.”

He knew his lieutenant. Nolan spotted the hallway full of sleeping demonstrators, marched past the first office in line, which was Adamson’s, into his own office next door, and slammed the door. A few minutes later, he came back to Adamson, fuming, and said, “What the hell do you think you’re doing?”