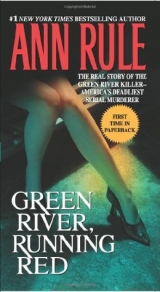

Текст книги "Green River, Running Red. The Real Story of the Green River Killer - America's Deadliest Serial Murderer"

Автор книги: Ann Rule

Жанр:

Маньяки

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

35

HEwould have some dramatic lifestyle changes in 1985, and that may have made a difference in the scope of his activities on the Pac HiWay and Aurora Avenue North. His solo travels would be curtailed certainly. His son, Chad, was getting older and more aware of what went on around him, and the man with so many secrets had become increasingly social. He felt at ease because he had bested them all for such a long time. He began to feel invincible.

Since he’d discovered Parents Without Partners, he had never lacked for feminine companionship; there were group activities in West Seattle and the south end every night of the week, as well as on the weekend. He dated a dozen or more of the women he met there. He met women at work, too, but they weren’t as responsive to him. One woman recalled that he overstepped personal space boundaries.

“I’d just started working there—sometime in the mideighties—and he came up behind me and started massaging my shoulders,” she said. “I wasn’t at all comfortable with that. I tried not to be alone with him. It was just a gut feeling, but it was real.

“We worked in the rework area together. He talked about gardening, swap meets, garage sales. He would tell me about his marriages briefly, [saying] he was on his third. He was always touching the women at work and once he was reprimanded for sexual harassment. He was upset, asking me, ‘Can you believe this?’ ”

She could indeed, but she didn’t tell him that.

He always spoke to women who lived in his neighborhood and he seemed friendly. Most of them were married, though, and knew him only as a neighbor. One woman, Nancy, who lived a block away, worked at the VIP Tavern on the highway. He didn’t drink much, usually a Budweiser or whatever was on draft in taverns, but he often stopped in at the Midway or the VIP taverns. “He was always fairly quiet, but also pleasant,” Nancy recalled, “and a few times he gave me a lift home. Since he never drank much, I felt safe getting a lift home from him…until one night.”

Instead of driving her straight home, he asked if she would mind stopping by his house for a few minutes. She saw no harm in that and vividly recalled sitting on his couch, drinking a beer. They were just having general conversation, and then he changed the subject to the Green River Killer.

“At the time, it was a popular subject,” she remembered. “He became very serious, to the point of being physically tense. He asked me what I thought about the killer and what he was doing. I told him that if I were a prostitute, I’d find a different way to make money. He asked what I thought about prostitutes. ‘Don’t you think we’re better off without them?’

“At that point, red flags went up left and right. I felt it was in my best interest to say: ‘Yup. We sure are. At least the streets are getting cleaned up.’ ”

He seemed very intense as he explained that the police hadn’t been doing their jobs, and she heard odd stress in his voice, a thrum beneath his regular voice: “We’re much better off without them [the prostitutes] littering the streets.”

Nancy was alert now; he had changed so much and fairly vibrated with tension. “He also knew that I knew quite a few psychics. He asked me if any of the psychics knew who the Green River Killer was. I told him that a lot of psychics had thoughts about it, but no one was talking.”

“Why?” he persisted.

She told him that, “for one thing, the police wouldn’t believe them. For another, they don’t want to die.”

He asked her what she meant.

Nancy studied him, choosing her words carefully. “The psychics are afraid that if they tell anyone who the Green River Killer is, they’ll be killed before the police would take any action, so they’re not saying anything—and they never will.”

Nancy kept her voice soft as she casually told him that she was tired and really needed to go home. Would he mind? “He seemed to relax a little bit and said we could go any time. I told him I needed to go right away. I stood up to leave, but he stayed seated.”

“Would you ever be a prostitute?” he asked her, his eyes boring into hers.

“No way!”

“That’s good,” he said, finally smiling and seeming to unwind a little. “I didn’t think you would. Have you ever?”

“Of course not,” she countered. “Have you?”

“That’s stupid,” he said.

“Just as stupid as your asking me.”

Now he stood up and said “Let’s go,” and headed for the door. But as they drove the few blocks to her house, he brought up the subject of the Green River Killer again, and she tensed inwardly. He stressed that whoever was killing the girls was doing the city a favor.

“I brought up their families, saying how sad it was that some of them had small children who would grow up without their mothers,” Nancy remembered. “He said this was something the prostitutes should think about before hitting the streets and he asked me if I’d changed my mind and ‘agreed’ with the prostitutes.

“Of course not! I just think it’s sad when you think about the families. Mothers and fathers who’ll never see their daughters again. Kids who won’t get to know their mothers. I just feel sorry for them.”

“They’re better off without them,” he told her flatly.

Nancy took a chance. “Do you really think that?”

He stared at her intently as they pulled up in her driveway and then said, “No! Of course not. Nobody deserves to die. Right?”

But he kept returning to one subject, as Nancy edged toward the passenger door. “Wanna hear something funny?” he asked.

“Sure.”

“I’ve been picked up by the F.B.I. and questioned for eight hours about the Green River Killer.”

“I was shocked and said, ‘What?’ But he seemed to be kind of proud about that, and just laughed and said, ‘Yeah. Can you believe that?’ ”

He explained that the police had found one of the missing girls’ phone number in his phone book, but he only happened to have it because he was a friend of her sister’s. He was quite calm at this point, and acted as if it was funny that he’d been a suspect.

He said he’d called his mother to come and pick him up at the sheriff’s office. “At the time, I didn’t connect the dots,” Nancy said. “He was always nice to me, always well mannered, opened doors for me, and never took a step out of line. When I first saw his picture on the news [years later], I couldn’t believe it.”

Long after she sold her house and moved to Hawaii, she would be grateful that she’d given him the right answers on the last night he drove her home.

Part Two

36

AFTER HE MOVED out of Darla’s West Seattle home in December 1981, he apparently had only a few lonely weeks. It was Christmas Eve when he appeared at a Parents Without Partners party at the White Shutters Inn on Pac HiWay and joined a woman named Sally Cavetto.* He seemed somewhat emotional and upset, a rarity for him. Sally would recall that he muttered several times that he had “just nearly killed a woman.” She assumed at the time that he meant he had almost hit a pedestrian.

Sally wasn’t concerned about it because nothing really bad had happened. She dated him until May or June of 1982, until another woman in PWP told her that she had caught herpes from him, and suspected that he was frequenting prostitutes. Sally broke up with him.

Hardly deterred, he continued to select dates from the endless source of single women in PWP. He became engaged to another woman and they actually set a wedding date—for June 1984. But once again he was dumped. Many of his girlfriends soon realized that he was seeing several women during the same time period. Moreover, he was apparently picking up prostitutes.

His stamina for sexual encounters was well known. All of his girlfriends knew he wanted sex several times a day, and he preferred to do it outdoors in an exhibitionistic way. Indeed, the fact that he demanded intercourse so often had led each woman to believe he was being faithful, at least at first. And then they realized he had a seemingly infinite capacity to perform sexually. But emotionally, he seemed shallow, unwilling or unable to show any real affection.

And then he met a woman named Judith in early 1985. They shared a common history of failed relationships. After nineteen years, her first marriage had turned out to be a shocking disappointment. She had finally accepted that her first husband, whom she divorced in 1984, was bisexual and leaning heavily toward being totally gay. She couldn’t live with his suggestions that he bring men home to share their marital bed. She was forty, and wasn’t that sure of her attractiveness to begin with. Having a husband who preferred men damaged her ego even more. Her family seemed to be disintegrating around her. She wasn’t sure what her older daughter was doing for money, and she was afraid to ask. She didn’t want to know the answer.

Judith was living in an apartment close to the Pac HiWay with a woman friend and her younger daughter, who was eighteen. All she had ever wanted to be was someone’s wife, a good mother, and keep a nice house. She hoped to remarry one day and she joined a group called Seattle Singles, but she didn’t meet anyone there who seemed to be a likely prospect. There were always more single women than single men. Besides, the men gravitated toward the younger, slimmer women in the group.

Judith’s roommate convinced her to attend one of the PWP country-western nights at the White Shutters, and she finally agreed to go even though she was shy and figured nobody would talk to her or ask her to dance. It was February 1985. She would always remember the date because she met a man that night who would change her life radically. It was his birthday and he told her the company he worked for had given him a couple of days off to celebrate it.

She was impressed by his job stability when he said he’d worked at the same place since he got out of high school—fifteen years. He mentioned that he was single, owned his own home, and even though he was driving an older brownish pickup truck with some rust spots on it, it was clean and had a camper on the back. He seemed pleasant enough, and he was definitely interested in her. They both liked country-western music, and when she left the White Shutters that night, she felt happier than she had in a long time.

He was four or five years younger than she was, but that didn’t seem to bother him. Judith had met his ex-wife, Dana, even before she met him and there appeared to be no bad feelings between them. That was a good sign, she thought. He persuaded her to join Parents Without Partners, and Judith was soon enjoying an active social life.

She had never worked and her skills were as “a homemaker.” When she met him, she was taking care of a woman and her two children, and also cleaning houses to make ends meet. She hadn’t planned on facing life alone at forty, and it wasn’t easy for her financially. She missed having her own house to take care of. Maybe her older daughter wouldn’t be running wild if she had a place to come home to.

This man’s kindness and his masculinity impressed Judith. She found him attractive, although she didn’t consider looks the most important attribute in a man. He was quiet, but he was fun, too. At first, she only saw him once a week at the PWP meetings, but then he started calling and asking her to go out with him. He was working the swing shift in the spring of 1985, so their dates were mostly for dinner in the late afternoon.

“We used to go down to McDonald’s on the highway,” Judith would recall later to Detectives Sue Peters and Matt Haney. “I’d be coming home [from work] and he’d be going to work. We’d sit and hold hands, have a hamburger. Then I’d either go home to my apartment or to his house. That was after. I didn’t go to his house till after a couple of months. Not right away.”

Judith wasn’t the kind of woman to jump into bed with a man until she really got to know him, so she didn’t spend the night at his house for the first two or three months they dated. Beyond that, she was still hurt and unsure of herself from the times her ex-husband brought men home.

“He treated me just so gentle and perfect. I’m remembering now one time when we were out camping on one of the mountains or in the parks or trees or someplace. Greenwater, I guess that’s what it was, out where you can just see the stars and everything. We were sitting in the back of the truck and talking and, you know, I let him know that I wasn’t used to a man wanting me. And, you know, personal things. And he was gentle. He didn’t rush or push. He wasn’t forward or anything. Any sexual relations we had [were], you know, slow and comfortable.”

Greenwater was a beautiful forested area, up Highway 410 east of Enumclaw, along the White River.

As time went by, Judith began to trust him and was relieved that his attention was focused only on her, and that he certainly wasn’t the least bit gay. He didn’t drink more than a beer or two, and she never saw him drunk. Once in a while, he would buy wine—Franzia, the kind that came in a box with a little spigot on the side.

They had similar interests—country-western music, of course—and they often went to garage and rummage sales. They both liked to go to the weekend swap meets at the Midway Drive-In Theater at Pac HiWay and S. 240th Street. She knew he liked the outdoors and going camping, and Judith looked forward to that.

Chad, his little boy, had his own room in his father’s house for when he stayed there on his weekend visitations. Unlike Darla, Judith didn’t shy away from the possibility that if she was with him, his son would be a big part of his life, even though his ex-wife had primary custody. He, on the other hand, didn’t object to her fondness for cats. His mother had always had cats. Judith felt as though the two of them just seemed to fit together.

He was “the best man” she’d known for a long time. “Nice, sweet, gentle,” Judith said. He took her to meet his parents, and they were nice to her and so were his brothers. “They were the ‘best’ family.”

He didn’t have any particular hobbies or any interest in sports, although he occasionally went fishing and there was always camping out. But he did that with her. He had neither close male nor female friends. She was his best friend, and that made her feel very secure. They did everything together. The only other people he talked about were people he knew at work. He was very proud of his job.

One thing he did not tell her about were the unexpected encounters he had had with King County sheriff’s detectives a few years before they met. That was another part of his life that had nothing to do with her, and he meant to keep it that way. Most of them happened before he even knew her, so it wasn’t really as though he was lying to her.

Judith had no idea that her lover had been stopped on the highway two or three times. Port of Seattle police officers had talked to him on August 29, 1982. Parked on a dead-end road, he had been only a hundred feet from sites where bodies were found a long time later, and he hadn’t been alone. Randy Mullinax had talked to him on February 23, 1983, and Jim Doyon had questioned him in April 1984 in front of the Kentucky Fried Chicken on Pac HiWay, when he appeared to be soliciting favors from a prostitute. He felt comfortable because he had been so agreeable with both detectives, and candid. Yes, he’d admitted, he did sometimes hire prostitutes, and he said he knew Kim Nelson aka Tina Tomson. But a lot of guys paid hookers on the Strip for sex.

The cops had all let him go, so he was serene in his belief that they didn’t suspect anything. He knew there wasn’t enough evidence to hold him. He’d been single then, a guy with a good steady job. What he did was his own business. Judith wouldn’t understand, so why even bother telling her now?

But then Ralf McAllister from the Green River Task Force had gone out and picked him up again in February 1985, the same month he and Judith met. That was after Penny Bristow got brave enough to file a complaint against him three years after the fact. That was a little dicier, but he’d explained it all away when Matt Haney questioned him about the 1982 attack on Penny. He readily admitted that he had tried to choke her, but it had only been a reflex action when she bit him during oral sex. Most men would have reacted the same way. It hurt like hell, but he had quickly come to his senses.

And the girl named Penny didn’t want to charge him formally. Without a complaining witness, they had no choice but to let him go. Actually, he was right in assuming they didn’t have anything concrete on him. But he didn’t know the third incident had elevated him to the level of an “A” candidate.

“He was certainly one of the primary people we had,” Frank Adamson said. “We followed him, and surveilled him, watching him stop and talk to prostitutes. We watched him staring at them. We talked to them, and we found no one he was hurting at that time. But he was certainly interested. Later, we were able to connect him to a number of prostitutes by talking to their girlfriends. We knew he had quite an involvement with prostitutes, but we didn’t think he was killing them.”

In the 1985 incident, Judith’s new boyfriend had even agreed to take a lie detector test and Norm Matzke gave him a polygraph. Matzke, who had long been the sheriff’s department’s polygrapher, following in the footsteps of his father, didn’t think this man was responsible for the Green River deaths. His pulse stayed even, he didn’t sweat a drop, and his blood pressure didn’t waver.

He himself was pretty sure he could always fool their fancy polygraph, but he decided that the next time they talked to him, he would refuse to take a lie detector test. There was no sense being foolhardy.

SOMETIME in either May or June of 1985, Judith agreed to move in with him. He was still living in the small house that backed up to the bank above the I-5 Freeway. Built on a good-size lot with room for their camping rig, it was a nice little house. Judith was thrilled to be living in her own home again. She was with a man who had perfect attendance at his job and who always came straight home to her. If he had to work overtime, he called her, and she appreciated that. He would go almost three decades without being late for work more than a handful of times, and that was only a matter of two or three minutes.

He was so considerate that he didn’t even ask Judith to get up and cook breakfast for him when he worked the early shift. He told her he’d stop at Denny’s or some other twenty-four-hour restaurant on his way to work. He handed his paychecks over to her and she would take care of the bills, but she always made sure he had enough money with him when he left for work to buy breakfast and lunch and fill up his gas tank.

When Judith’s younger daughter and her boyfriend and their babies needed someplace to live until they got back on their feet, he agreed that they could stay with him and Judith. She realized that not many men would have done that. He was someone she could count on even though he didn’t seem anxious to get married again. She figured that would happen some day.

In the meantime, theirs was a very comfortable relationship. They went camping, watched television together, and indulged a mutual passion: collecting, restoring, and selling things that other people had either thrown away or sold cheap. “We’re pack rats,” Judith said. “We like to save stuff. We don’t like to see stuff go in the landfill. We’d always go to the swap meet. We’d have yard sales. Oh, it was great because my ex-husband never let me have yard sales. We have so much fun doing that together.”

Both of them were amazed at some of the things other people threw away at the landfill, and by the “free piles” left behind at the Midway Swap Meet at the end of a weekend. “Chad and him would look at the free piles,” Judith said fondly, “and maybe find something that needs to be fixed. We’d take things home and fix ’em, and so…like a bicycle. We got all kinds of bikes. He’d fix a bike after getting it for free, and sell it to a little kid who’d be happy for getting a bike for five or ten dollars. And a toy. He’d pick up a toy and maybe the grandkids would like to play with it.”

They found that they could make more profit by having frequent garage and yard sales at their house than they could by renting a space at the swap meet. Their neighbors grew used to seeing the “Yard Sale” sign out when the weather was good.

Pat Lindsay, who worked for the U.S. Postal Service, had sold him his house in 1981 and still lived close by. Although something about him always gave Pat a weird feeling, she liked Judith and often chatted with her as she presided over a yard sale. “They always had sales going, and baby kittens. Judith loved her cats and kittens,” Pat recalled. “I think the funny thing about him was that he didn’t seem to remember me at all. I’d sold him his house, but he didn’t recognize my face or connect me to that when I stopped by during a yard sale. I could have been a complete stranger as far as he was concerned.”

Once, before Judith moved in, Pat recalled that he had approached a couple of men in the neighborhood and asked them for help ripping out a carpet in one of his bedrooms. “He said he’d kicked over a can of red paint or spilled it somehow, and he needed to get it out of there and replace it. They helped him get it into his truck, but he never explained how he could have spilled so much paint.”

Once he had the carpet in his pickup, he wouldn’t have trouble getting it out at the county’s Midway landfill off Orilla Road. The men noted that he had a kind of hoist with cables and a “come-along hitch” bolted to his truck.

Despite all the things they found “Dumpster diving” or scanning other people’s sales for free “stuff,” he never bought Judith any presents. She didn’t mind. She had her rings from her first marriage melted down and redesigned. As far as any jewelry purchases, that wasn’t something he would buy to surprise her.

“We did all of that together,” she said, explaining that he never brought gifts home for her. He just wasn’t like that. “We went shopping together.”

There were so many things she did with him for the first time in her life. She went on her first plane trip when he took her to Reno. She loved the camping, either at Leisure Time Resorts campgrounds, where they split a membership with his parents, or roughing it. “At the very beginning of our relationship,” she recalled, “we went camping up on the Okanogan ’cause he had a week off. That was just so [much] fun and delightful. He was so nice and gentle—I hadn’t known him for very long.”

They came back from the largest county in Washington and the Pasayten Wilderness that led into Canada via the North Cascades Highway, and she was thrilled by the grandeur of the view and the Ross Dam, with its clear blue water. “I never got to go camping before,” Judith explained.

They visited several Leisure Time locations, mostly the site up past Ken’s Truck Stop off I-90, but also those at Ocean Shores on Washington’s Pacific Coast; Crescent Bar in Concrete, Washington; and Grandy Creek. At Leisure Time, they could pull their camper in and have electricity and water hookups, and cooking grills.

They finally got married in their neighbors’ front yard on June 12, 1988. Judith was the one who gave him an ultimatum about making a permanent commitment. “I told him after three years, he’s not getting rid of me. ‘We’re getting married!’ He said okay.”

The Bob Havens hosted the event, and most of the people who lived along their street attended. Everyone liked Judith. She was a sweet woman, and he was a good enough neighbor.

They soon bought a bigger house down in Des Moines, and Judith went to work to help pay the mortgage. She sewed on a commercial machine for a SCUBA equipment company there, and later worked at the Kindercare day care, both Des Moines businesses. He kept his job as a painter. He took great pride in his work, but he was always careful about cleaning up before he came home. He didn’t have a spot of paint on him when he left the plant and he even combed his mustache to be sure all the paint flecks were gone.

They were definitely moving up in the world. Judith was happy in her marriage, and she enjoyed being with her husband’s parents and brothers. She worried a lot about her daughters, especially her oldest, who had gone off to the East Coast, but she knew she could count on her husband.