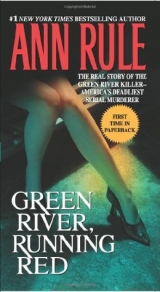

Текст книги "Green River, Running Red. The Real Story of the Green River Killer - America's Deadliest Serial Murderer"

Автор книги: Ann Rule

Жанр:

Маньяки

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 27 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

Stevens was the eldest of three children, all adopted by a caring Spokane pharmacist and his wife. Billy Stevens was less than a week old when they brought him home, and he grew from a chubby child to a bearlike man, tall and lumbering with a big belly. He wore dark-rimmed glasses and had tightly curled brown hair. Indeed, he looked remarkably like one of the four widely disparate sketches of the Green River Killer as described by witnesses to possible abductions.

Just as Dick Kraske had remembered fingerprinting Melvyn Foster when Foster was first arrested in Seattle, Tom Jensen of the Green River Task Force recalled investigating Stevens in a King County burglary case nine years earlier. When Jensen heard his name, he had no trouble recalling the smooth-talking, overweight burglar he’d once interviewed. In 1981, Billy Stevens was being held in a work release unit in the King County Jail with five months left to serve. One day he was supposed to be carrying garbage out, but he’d just kept right on going.

It was what Stevens had stolen that made him most interesting as a Green River suspect, and where he had stolen it: He had taken a police uniform, Mace, surveillance devices, bulletproof vests, and other police equipment from a store out on Pac HiWay, a business located across the highway from the Blockhouse Restaurant, kitty-corner from the Midway Tavern, and just down the block from the Three Bears Motel. Stevens himself had lived in a nearby apartment at the time.

Now, he’d been arrested with guns, license plates issued to police vehicles, and a police car. Because of the constant rumor that the Green River victims had been killed by a policeman, Stevens’s collection of police gear and weapons put him quickly into the “A” category. He was not just a “person of interest”; Stevens looked good enough to be a “viable suspect,” although the task force was careful to keep that appellation to themselves for as long as they could. Stevens fit neatly into so many facets they sought in a suspect.

And with good reason. The face Billy Stevens presented to the world was only a facade. In truth, he was a con man on the level of “The Great Imposter.” Ferdinand Waldo William Demara Jr. defrauded scores of people who believed he really was who he seemed to be. A brilliant con man, “Fred” Demara managed to masquerade successfully as a monk, a Canadian navy surgeon (who actually performed complicated surgeries successfully), a cancer researcher, a deputy sheriff, and a professor. Demara, who never graduated from high school, much less college or medical school, had a thirty-year career, although he was sporadically arrested for fraud, theft, embezzlement, and forgery. Had he chosen to pursue any of his “careers” legitimately, he could have accomplished the necessary education easily. Instead, he was a fraud, a man who some considered to be a true multiple personality.

It was the same with William Stevens II. He had a solid legal education after his years at Gonzaga, but he could never have passed the bar in any state that checked his background. He had a felony police record. He had also studied psychology at the University of Washington in Seattle, and had allegedly graduated in 1979 with a degree in pharmacology. He claimed to have been a second lieutenant and a military policeman in the U.S. Army, and to have applied to the Seattle Police Department to become a patrolman. Instead, for all his years at Gonzaga, and even before that, he was supposed to be in jail.

Stevens’s early life seemed uneventful enough. He’d been born in Wallace, Idaho, on October 6, 1950, adopted by William and Adele Stevens, and raised in a quiet neighborhood north of the Spokane city limits, attending Jesuit schools and graduating from Gonzaga High School in 1969. His father owned the University Pharmacy, a block from their home, for thirty years, hoping that his son and namesake would take over the business one day. Young Billy was not particularly close to his siblings by adoption, consumed as he was with his own hobbies and interests. He was a police buff early on, fascinated with the lifestyle and paraphernalia of law enforcement. An inordinate number of serial killers are police groupies, eager to move in the same circles as real cops.

Although he had spent some summers working in the family drugstore, Stevens never really wanted to be a pharmacist. He had tried, unsuccessfully, to join the Seattle Police Department, but he had a lousy driving record.

Stevens was one of the most interesting suspects yet to rise to the forefront in this marathon investigation. His photo first appeared in the media at the end of January 1989, when the handcuffed fugitive was arraigned in a King County Superior Court. His attorneys asked Judge Donald Haley to release Stevens on bail because his elderly parents were ill and needed his help. “Our position,” Craig Beles said, citing Stevens’s success in law school, “is that Bill is a remarkable example of what rehabilitation can do.”

The judge asked somewhat wryly why Stevens hadn’t responded to two warrants for his arrest in 1981. Stevens explained that he had given police information on his fellow prisoners and he’d been afraid that, as a “snitch,” his life was in danger, so he had walked away from work release and was afraid to go back.

In reality, he had never been a police informant.

Where had he been between 1981 and 1985 when he enrolled in law school in Spokane? Stevens proved to have had a lifestyle so peripatetic that it wasn’t easy to trace the many places he had lived. For the moment, however, he was safely behind bars again in the King County Jail, finishing the sentence he had walked away from ten years before.

The Green River Task Force found that Stevens had crossed the Canadian border into British Columbia shortly after his 1981 escape. There he lived as a “house guest” of a Vancouver couple for about four months. They had acquiesced to his staying there at the request of a mutual friend. They knew him as “Ernie,” and thereafter, he changed his name to “John Trumbull.” He explained that he was setting up an import business. He never seemed to have much money, but he explained that, too, saying he was waiting for funds to be released. He didn’t pay rent, but he bought some groceries, and helped with the dishes and the housework. They found him an amiable and polite guest.

“He was very organized, tidy, and a good talker,” the husband of the couple recalled. “He dressed well and gave the impression of being an army man. He slept on a couch in the den and spent his time watching TV and reading.”

Toward the end of Ernie/John’s time with the Canadian couple, he made several overnight trips. He said he was going to Seattle. Then, in late summer 1981, their visitor left. They weren’t sure where he was going.

William Stevens’s/John Trumbull’s trail picked up again in a southwest suburb of Portland. He bought a house on Southwest Crestline Drive for $108,000, a Roman brick with a double garage and a daylight basement. To help with the mortgage, he occasionally took in tenants in an apartment in that basement.

The task force looked at an Oregon map and saw that the house was within five miles of the Tigard/Tualatin site where the remains of four young women had been found, and within a mile of the location of Shirley Sherrill’s skull and the partial skull of Denise Darcel Bush.

How Stevens supported himself was a question. Whether he was a danger to women was also a mystery. When I sorted through the hundreds of emails and notes I took during phone calls about the Green River Killer, sometimes I found circumstances and tips that seemed to match. I remember finding one that struck me as eerily connected to the time William Stevens lived near Tualatin.

A few years after the Portland area phase of body discoveries and attacks on women by would-be stranglers, I received a phone call from a woman who lived in Washington County, Oregon. She was embarrassed and made me promise I would not reveal her name. I promised.

“I’m married now,” she explained, “and I don’t live the same kind of life at all. But then I did pick up men at bars and taverns, and I was drinking too much.

“I met this one guy at a tavern near Beaverton [a few miles from Tigard and Tualatin]. It seemed to me that he was taller than average, and I do remember that he had one of those great big country-western-style belt buckles. We drove out to a field that was quite a ways from the place where I picked him up. And…well, we had sex outside in a field someplace. Afterward, I started walking back to his truck and he suddenly reached out his arm and grabbed me by the elbow. I looked down and saw that I had almost fallen into what looked like an open grave. The worst thing was that there was a woman down in there, and I think she was dead.

“When I got back to my car, I was so grateful to be alive that I just tried to put it all out of my mind. But I know there was a grave, and I know there was someone in it.”

The “field” that the woman remembered was close to Bull Mountain Road and she believed that was where the man had taken her.

I turned the information over to the Green River Task Force, just one of more than the thousands of possibles it would document, but I kept her name out of it. If they thought it was worth following up, I could get back to her and see if she would talk to them on the condition that she remain anonymous. I don’t know if she ever called them, although I urged her to do so.

When William Stevens’s name came up, I remembered another woman who had written to me from Oregon. She told me her name was Marisa, and that she had once been a prostitute in Portland. She had described a shorter, thinner man than Bill Stevens appeared to be, but terror and shock can warp such perceptions.

Marisa’s recall of her meeting with a stranger was, however, precise. I don’t know her real name, but everything she told me about life in The Camp during the early to mideighties was validated by official police files.

Marisa has lived an entirely straight life for many years, and people who knew her after the eighties as a successful career woman would never guess what her former life was like. She was working the streets twenty years ago because she had been badly burned in an accident in a business she’d started and she was tired of being hungry and behind in her rent.

In 1983, she was thirty but looked about nineteen. “I remember being on Third Ave and Taylor Street about eleven PM in downtown Portland when he motioned to me to get in,” she recalled. “I had been out there trying to get up rent money.” Marisa usually worked in expensive hotels, but rainy Sundays were always slow, and she broke her first safety rule by going out on the street. Halloween decorations hadn’t been taken down, so it could have been early November. She got into a shiny red Ford pickup truck, which was clean and new. “The word on the street was that the GRK was driving an old beat-up van so I figured I was safe. And besides, I told myself the GRK was in Seattle.”

She broke her second rule, one shared by most working girls: never leave the downtown area. But Marisa was having a lucky night and had made almost all of her rent money. There were no other girls out that night and she decided to turn one more trick. “I asked him what he was interested in. He didn’t answer. He stayed quiet and drove with purpose as he headed to I-5. I thought he was just shy. I told him I didn’t want to leave downtown. He said he didn’t feel comfortable because of the cops and he wanted to go to his house.”

She was about to break the third rule of the street: never go to anyone’s house. “I thought what the heck. I can break a rule because I am on a lucky streak.”

The man didn’t even glance at her as he raced along the I-5 Freeway, heading south, and then took an off ramp near Tigard. “He pulled into his garage and the automatic door closed behind us.” They went into his small two-bedroom house.

She assumed he would ask for oral sex; most men did. He signed a cashier’s check for $80.00 and gave it to her. She saw the name “Robert Thomas” on it. She thought he was probably a truck driver because they often had cashier’s checks, but she was puzzled that he remained distant and seemingly disinterested in sex. “In fact he was unable to get it up. I thought well what the hell—you bring me all this way for nothing.”

Suddenly, the stranger leapt from the bed, and grabbed a rifle from behind a door, aiming it at her. “My life flashed before me,” Marisa recalled. She assumed he was upset with her because he couldn’t achieve an erection, so she started talking loud and fast, telling him she would give back the check and she ran into the bathroom, locking the door. She was naked, a fourth rule she had broken. Frantic, she dressed hurriedly, all the time shouting through the door that she was searching for his check.

Dressed now, she opened the bathroom door, only to find him standing there with the rifle pointed at her head. She threw the check at him, saying “Here! Here it is. Now let me go!”

She was trying to snap him back into reality, but it wasn’t working, and he had no intention of letting her go. She darted past him to the front door, only to find it had three locks. Why, she wondered, would a man who lived on a quiet cul-de-sac need three locks? As she struggled to turn the bolt, he began to beat her on the head with the rifle’s butt.

Marisa turned as he started laughing maniacally. “He looked like a kid on a ride at Disneyland, his eyes all lit up and happy. With every swing of the rifle into my head, he got happier. This guy was psycho,” she wrote. “He was getting off on it! This is how he gets off! I remember his big glasses, the same style he wears today…and his hair-do the same…and his stature…not that big a man…not that small either…that same dumb sneaky look he has today. With that sly sparkle in his eyes.”

It was evident to Marisa that he had brought her to this house to kill her, but he was taking his time. “He wasn’t slamming the rifle with all his might, just cat and mouse style.”

She remembered she had Mace in her front pocket, and she squirted it in his face, but his glasses blocked most of it. “He hit me left, then right, then left, then right, and beat up my forearms pretty bad. He finally pried the Mace from my hands and began spraying it in my face. Then I began to pray. My eyes burned with excruciating pain, but I would blink often to see what he was doing.”

Now, she turned her attention to the front door, getting a mental picture of where the locks were. She lunged at the door to try to open another lock—the dead bolt. He continued to spray her with the Mace. “I grabbed a pillow on the couch near the door to protect my face. I kept him thinking he was winning so he wouldn’t get even more forceful. That would buy me time for the third lock.”

Even so, she was losing strength and felt she was going to die. “I was hurting bad and my eyes were on fire.”

Her attacker was clearly enjoying himself. “That part is very scary; seeing him be thrilled over hurting someone who wouldn’t hurt a fly—me.”

She knew she had to get out because the Mace and her injuries were wearing her down. And then, for a moment, he seemed to tire, too. With her eyes almost entirely swollen shut, she twisted the dead bolt one more time.

“To my surprise, it unbolted and the door swung open. ‘GRK’ was surprised too.” Marisa ran blindly across the street and down four houses where she knocked and called out, “Please help me!” It was about twelve thirty AM, but a woman opened the door for her and led her to the bathroom where she washed her eyes.

The police arrived, and Marisa told them that a killer had a friend of hers hostage in a house nearby. Afraid they wouldn’t believe her if they knew she was a prostitute, she lied and said he’d picked them both up at a bus stop in downtown Portland. She tried to show them the house but she could hardly see, and the homes all looked alike. There were no trucks parked outside. As she stood on the porch of the woman who had helped her, Marisa saw a big sign right at the Tigard/Tualatin Exit from the freeway. It blinked on and off: Jiggles. She’d heard of it; it was a topless lap dance place.

The police gave up their search after she admitted that she didn’t have a friend in any of the houses in the cul-de-sac.

“Please understand,” she wrote to me, “living as a sex worker, I felt I had relinquished my rights as a citizen and that I wasn’t worthy of protection. I was doing an unlawful thing even though it was in the name of survival.”

The cops drove Marisa back to downtown Portland to her car. Her car keys were missing, and it cost her everything she’d earned earlier that night to pay a locksmith in the wee hours of the morning, but all she wanted to do was go home. Her friend, Tatiana,* who also worked the premier hotels in Portland, took care of her for a few days until her bruises began to heal and she could move without pain again.

Years later, when she watched the news bulletins from Seattle, and recognized the man in handcuffs, she felt sick to her stomach. An artist who remembers details, Marisa has always believed that she escaped from the Green River Killer. “We knew many of the girls who got killed,” she wrote. “We never thought they had any family. Most of them were on drugs—methamphetamine and marijuana. Sad to say that those girls didn’t have a chance in the world, even at their young age. Many were so hooked on drugs, they would have died of an overdose. I do wonder about the ones who came up missing and are not on the GRK list. Most of them were very sweet girls. They were still children in a way.”

Marisa herself went to New Beginnings in 1985, got off the street, and changed her life completely.

45

ONE WOMAN who definitely met Bill Stevens was Sarina Caruso, forty-four at the time, who rented the basement of the house on Crestline Drive from September 1984 to January 1985. She knew Stevens as “John L. Trumbull,” and although she found him somewhat odd, she didn’t suspect he might be dangerous. Caruso, who had just gone through a divorce, worked as a nursing assistant and considered herself lucky to find an apartment that cost her only $200 a month.

In the time she knew him, she never saw Stevens/Trumbull with a date, although she sometimes heard women’s voices in his upstairs quarters in the middle of the night. He was a night owl, though, and would often be barbecuing in the backyard at two or three AM. He had no friends, and she thought he might be an undercover cop or a C.I.A. agent. He wore several different uniforms that made it look as if he worked for the gas or electric company or as a repairman. But he had a gun collection and appeared to be fascinated with crime—to the point that he hung “Wanted” posters all over his house. He wore shoes with crepe soles, which allowed him to move so quietly that he would suddenly be behind her when she hadn’t heard him approach. He also owned a lot of telephone equipment, a photocopier, and other equipment that he told her he used to analyze fingerprints. One of his many idiosyncrasies was that he would never allow anyone to take a picture of him.

Caruso wasn’t too concerned about his eccentric ways, even when Stevens stole her chain saw and her marriage certificate. She worried a lot more when she saw that he had dressed mannequins in clothes she had thrown away. And even more when he cut the female dummies into pieces.

When she found bullet holes in Stevens’s bedroom wall, Sarina Caruso gave notice that she planned to move. Stevens/Trumbull had always told her that he was adept at placing secret “bugs,” and he’d offered to bug her ex-husband. Now she wondered if he had secreted listening devices in her apartment.

On the last day she saw him, Caruso had returned to pick up the remainder of her possessions and he said to her, “How are your nerves today?” He then began locking all the doors. Nervously, she let him lead her to the basement where he showed her the secret room he had there, a room hidden behind a bookcase that would slide open when he flicked a switch. Although she had occupied most of the basement, he demonstrated how he had been able to open a secret door into her area that couldn’t be opened from her side.

That did it. Caruso grabbed her stuff and left, but not before Stevens insisted she take a dozen pornographic videotapes as a good-bye gift.

Sarina Caruso recalled Stevens’s high-pitched voice and that he perspired heavily. “There were things I wasn’t comfortable with,” she told reporters later, “but I just thought he was bizarre and antisocial. I feel dumb now. I certainly didn’t think he might be a killer.”

Perhaps he wasn’t, but William Stevens II was a man with many secrets. Fellow students at Gonzaga were shocked by his arrest for escape and burglary. A lawyer who had graduated a few years earlier and once worked with him on the Student Bar Association recalled Stevens as “very dedicated” to duties for the group, but said he seemed lacking in commitment to his law studies. He often missed class. Even with his law school peers, Stevens was mysterious. They realized later that none of them had a phone number where they could contact him directly.

They had no inkling that most of Stevens’s life was a very elaborately constructed lie. To give himself official status, he used a crossroad of a town seventeen miles south of Spokane—Spangle—where he had license plates registered to the Spangle Emergency Services and Rescue Unit. Sometimes he purported to be the director of the EMS in Spangle, and sometimes he said he was the police chief. The town wasn’t big enough to support either a rescue service or a police department.

One fellow law student knew Stevens was intrigued at the thought of being somehow involved in law enforcement. “He told me that after he finished law school, he was going to be a motorcycle officer for the Washington State Patrol,” the man said. “That seemed bizarre. Why would he bother to go all the way through law school if that’s what he wanted to do?”

Other law students had found Stevens gregarious and likable, and always busy. But no one ever thought of him as a threat; he was just different.

All through the spring and half the summer of 1989, Green River Task Force investigators and Spokane County detectives were checking out Stevens’s life over the prior eight years. Satisfied that they had more than enough to go on by July 12, they obtained search warrants for two residences in Spokane. One was the home where Billy Stevens had grown up, and where he still had a room in the basement, and the other was a rental home his parents owned. The search warrants were very long and complicated, listing dates and times of the disappearances of the victims, followed by Stevens’s whereabouts during those periods. It did appear that his constant sweeps around Northwest highways placed him close by when many abductions took place. The warrants also specified all kinds of police paraphernalia, records, credit card slips, suspicious books and photos, videotapes, and other items they hoped to find among Stevens’s possessions.

There were, however, more reasons than just his proximity to the crime scenes. Stevens had made his feelings about prostitutes known to some of his acquaintances. One—perhaps his closest friend and a former classmate at Gonzaga—was a lawyer and a Spokane County deputy public defender named Dale Wells, who was also thirty-eight and single. Wells had acknowledged to Spokane County detectives that he and Stevens were close friends and had often discussed criminal cases, especially the crimes of Ted Bundy. Another topic that interested Bill Stevens was prostitution. He had denounced prostitutes to Wells and said they spread AIDS.

“He talked about them a lot,” Dale Wells said, emphasizing that Stevens had demonstrated “extreme hatred” for anyone who resisted him and often said of his perceived enemies: “They need to be killed.”

While Stevens appeared to have no romantic relationships with women, Dale Wells was involved with a woman he cared deeply for—and she for him. He appeared to be a sensitive and honorable man, and he was very troubled when Stevens became the top suspect in the Green River murder cases. Wells, whose career was dedicated to representing indigents, many of whom he thought were falsely accused, agonized over betraying his friend.

On the other hand, he was an attorney, sworn to uphold the law, and he felt he had to tell investigators what he knew. He also regretted that he had given Stevens two handguns, one of which was a .45-caliber pistol. That had resulted in federal charges against Stevens for being a fugitive felon in possession of a firearm.

If Stevens berated Dale Wells for turning against him, there was no proof. He may not have even known about Wells’s defection from his camp. And he was still possessed of the braggadocio that marked his personality. He had to be placed in an isolation section in the King County Jail after he told a judge that he had two hundred pages of notes from his interviews with another prisoner who was a convicted murderer. Stevens said he planned to use that information in a thesis to help him earn his Ph.D. in psychology. That put him in the “snitch” category, more than enough to make him a pariah in jail.

When asked how he supported himself during his eight years of freedom after his 1981 jail escape, Stevens said he made a good living buying and reselling cars, and that he was currently applying for an auto dealer’s license.

Deputies and detectives served the search warrants in Spokane and came away with more than forty boxes and bags, many containing pornographic material, dozens of photos of nude women in sexually explicit poses, some with Stevens, and eighteen hundred videocassettes. Detectives would have to view all of that material, looking for a familiar face. Perhaps some of the Green River victims’ images might have been caught in Stevens’s massive collection.

No one envied the detectives who drew the assignment of wading through the stultifying XXX-rated material that the seemingly affable law student had managed to hide in his parents’ home and rental property. If any of the victims’ photos were in the boxes and bags, what were the chances they would be recognizable? So many of the dead teenagers had dyed their hair, worn wigs, and changed their makeup, that it had been nearly impossible to spot them in mug shots. Stevens’s collection of grainy, amateurish porn videos made it difficult to recognize familiar faces.

Stevens himself, still in the King County Jail on his earlier charges, issued a statement that came exactly seven years after the day Wendy Coffield’s body was believed to have been discarded in the Green River. If he knew that date was a grim anniversary, he didn’t mention it. Instead, he was outraged and stunned. “I am not the Green River Killer,” he said through his attorney. “The Green River Task Force has not treated me or my family fairly. They have made me out to be a very bad person and I am not. People should know the fact that I have never hurt anyone in my life.

“If I knew anything about any of this, I would have told the task force long ago, but now I fear I have become the excuse for the time and money they have spent.

“I will discuss the matter in an orderly and honorable fashion in a court of law.

“The task force has put my family and me through a living nightmare that I would wish on no one. I want to serve out my remaining few months and get on with my life.

“Thank you.”

HIS FAMILY was going through a “living nightmare,” although the task force investigators hadn’t caused it. They were only doing their jobs. Bill Stevens’s brother had been taking care of their elderly parents. Their mother, Adele Stevens, had died earlier in July, and William Stevens Sr. was suffering from advanced brain cancer. No one could estimate what emotional pain Billy Stevens had caused them over the years.

Everyone who followed the seven-year plague of the Green River Killer had settled on a favorite suspect. And so had I. I was convinced in July of 1989 that William Jay Stevens II was the serial killer the task force had hunted for so long. Everything seemed to match my preconceived ideas of who the killer was: a middle-aged male Caucasian, very intelligent, a sociopath with charisma and cunning, perhaps someone pretending to be a police officer, someone who traveled continually, and who liked playing games with real cops.

I hedged my bets a little when I was contacted by reporters, although I did say I believed that charges would soon be forthcoming in the Green River murders. I had a contract to write about the Green River Killer, and I was finally ready to start my book.

I had even more reason to believe I had chosen the real Green River Killer a few months later. On Friday, September 21, 1989, I drove the three hundred miles from Seattle to Spokane where I was to teach a number of seminars over the weekend for the Washington State Crime Prevention Association convention. Daryl Pearson of the Walla Walla Police Department was in charge of providing speakers for an audience consisting of police officers, attorneys, probation and parole officers, and the media. I had done a phone interview with the Spokane Spokesman Review-Chronicle that appeared in the paper just before the convention. Among other subjects, I answered questions about the likelihood that the Green River investigators were heading toward an arrest. I certainly didn’t know, but it was a subject readers always wondered about. This time, I felt as confident as some of the task force members did, and said so, although I didn’t mention the suspect’s name.

The convention was held in a Spokane hotel, and I was a little taken aback to find I was scheduled to give my two-hour slide presentation on serial killers—featuring the Ted Bundy case—four times on Saturday and twice on Sunday morning. Although I had expected to speak once on each day, there were so many attendees that every seat was full at each session, even when the folding doors between two meeting rooms were opened to double the size.