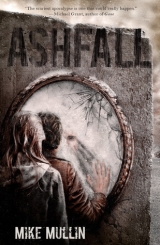

Текст книги "Ashfall"

Автор книги: Mike Mullin

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Chapter 21

Darla led me into a room filled with rabbit hutches, wire-mesh cages suspended from the ceiling by wires. The cages were linked together in two long rows, with eight cages per row. Two or three rabbits lay in most of the cages, just one in a few of them: maybe twenty or twenty-five rabbits in all.

I’d get teased mercilessly if any of the guys at Cedar Falls High heard me say this, but they were cute. Floppy gray ears and gray noses topped their white bodies. They were big, too, at least twice the size of the rabbits I used to see in pet shops.

Darla moved along the row of cages, pulling water bottles out of the little rings of wire that held them suspended beside each cage. I helped her gather up the bottles and then held them as she refilled them, pouring water out of a five-gallon bucket.

“They’re all sick,” Darla said.

“They look okay to me. Kind of cute, actually.”

Darla glared at me. “They’re meat rabbits.”

“Oh.”

“Look at this.” She reached into a cage and pulled a rabbit out of a stainless steel bowl. It had been flopped across the bowl, panting a little. “They started running a temperature and drinking way more water not long after the ashfall. I put extra water bowls in their pens, but they just lie there in the water.”

“Um—”

“I guess it’s not a big deal; we’d have to butcher them soon anyway. I’m almost out of rabbit feed, and I can’t get the dumb bunnies to eat corn.”

“Weird.”

“Can’t say I blame them much, I’m getting sick of corn, too.”

“So if you’re going to kill them all anyway, what’s the problem?”

“It’s just . . . I don’t know what it is.” She spoke in a softer voice than I’d yet heard her use. “It must be something related to the ashfall . . . . What if it gets us, too?”

I couldn’t think of anything to say. The same thought had occurred to me, that the ashfall might be killing me, especially every time I coughed up blood. But I didn’t want to tell Darla that. I didn’t want to admit to her that I was afraid.

“This guy, I named him Buck.” Darla looked at me. “You get it? Buck and he’s a buck. . . .”

I must have had a blank look on my face. I had no clue what she was talking about. And I was still wondering if the ashfall was somehow poisoning us.

“City people,” she said, scowling. “Hold him for me, would you? No, by his haunches, upside down. Hold him tight, okay?”

I held the rabbit as she directed me, upside down in front of me. He waved his front legs feebly. Darla grabbed his head and pulled down sharply, twisting it. There was a soft pop, and he went limp in my hands. I was so startled, I dropped him.

Darla picked up the dead rabbit and said, “Bring the water, would you?”

I followed her into the main room of the barn, carrying the five-gallon bucket. A plastic double-bowl sink was built against one wall, with a couple loops of twine dangling from a beam above one of the basins. Darla slipped the dead rabbit’s back legs into the twine loops so it hung upside down over the sink. Then she pulled a four-inch knife out of a block on the workbench beside the sink and began sharpening it on a rectangular stone.

I put down the bucket and watched. I wasn’t exactly sure what she was doing, but I had an idea it wouldn’t be entirely pleasant.

Darla reached up and ran her knife around each of the rabbit’s hind legs, right below where the strings held it suspended above the sink. Then she cut a slit along its inner thighs on each side. She grabbed the skin and peeled it down the hind legs, turning it inside out as she went.

It wasn’t nearly as gross as I imagined it would be. For one thing, there wasn’t much blood. The skin peeled smoothly off the legs, although I could see Darla was pulling hard on it. Beneath it I saw the rabbit’s muscles, pink and gleaming in the dim light.

It was uncomfortable to watch. I wondered what I would look like, dangling by my legs, skin slowly peeled back from the ankles down. I told Darla, “I’m going to go see if your mother needs any help.”

She looked over her shoulder at me. “Grossed you out, huh?” She smiled—in victory, I imagined.

“Uh, no, it’s not—”

“So you’re a vegan or something?”

“No, I like meat.”

“You just don’t want to see where it comes from?”

“I know where it comes from: nice plastic-wrapped containers in the supermarket. . . .” I smirked and then shut up so I didn’t sound like a wimp.

Darla was quiet for a few seconds. “Not anymore.”

“Yeah. Look, you’re right. I should learn how to do this.”

“Fine. Watch, then.” She made a couple quick cuts around the tail and pulled on the skin, tugging it down over the rabbit’s hindquarters.

“I’ll learn it better if you let me try.”

Darla shrugged and handed me the knife. “Cut straight down the middle of the belly, from the tail to the neck. Try not to cut too deep. We only want to slit the skin now. We’ll gut it next.”

I tried sliding the knife gently over the skin. I wasn’t cutting anything. Darla put one hand over mine and pushed down, forcing the knife firmly into the skin right below the tail. Together we drew the knife downward, and the pelt opened up like a bathrobe, exposing the pink muscle beneath.

“Okay, now grab the skin and pull down. Hard.”

I did, and the skin peeled off the carcass like a sock, all the way down to the rabbit’s forelegs.

“This part is kind of difficult; let me have the knife.” Darla cut the rabbit’s front paws off with a pair of garden shears and tugged the skin off its forelegs. Then she pulled the skin down over the rabbit’s head, making tiny cuts here and there with the knife as she went. In less than a minute we had one very naked-looking rabbit carcass and an inside-out skin.

“What now?”

“Now we have to gut it.” Darla made a deeper cut down the belly of the rabbit and pulled the muscle aside, exposing a gray, wormy mass of intestines and organs. She reached into the rabbit and pulled out its guts with her hand. It was so disgusting I had to look away.

“I’m going to pull out the liver, kidneys, and heart now,” Darla said. “Pour a little water over them, would you? They’re good eating.”

I sloshed water over her hands while she pulled the dark red organs out of the rabbit’s chest. She dropped them into one of two buckets in the other basin of the sink. The second bucket held the nasty, gray, spaghetti-like intestines.

I kept pouring water for her as she washed the inside of the carcass. She jammed her finger through the hole where its tail had been. “To clean out any last bit of lower intestine,” she said.

Once Darla was satisfied that the carcass was clean, she taught me how to butcher it. She deftly cut off each piece of meat, naming it as she did: hindquarters, loins, etc. Pretty soon we’d filled the clean bucket with rabbit meat, ready for cooking.

“Will you take the meat in to Mom? I want to try tanning this skin. We might need it.”

“Okay.” I picked up the bucket of meat and shuffled out of the barn. It was getting more difficult to see as real twilight replaced the fake yellow version we suffered with during the day.

I found Mrs. Edmunds in the living room feeding the fire. “Darla asked me to bring you this rabbit meat,” I said, holding up the bucket.

“Lovely, it’ll be so nice to have some meat for a change. But I didn’t think she was planning to butcher any of them for a while.”

“It was sick. She didn’t seem too happy about it.”

“Oh dear. The Lord provides—maybe we were meant to eat rabbit tonight.”

“You don’t suppose it could hurt us, could it? Eating meat from a sick rabbit?”

“We’re not sure why the rabbits are sick. Probably not if we cook it really well. I guess we’ll find out. Tell Darla I need at least an hour to let it stew. Two would be better.”

“Okay.” I handed the bucket to Mrs. Edmunds and left the house. I figured it might be hard to find my way back to the barn since it was getting so dark, but it turned out to be easy. Darla had flung the big sliding door fully open and lit a makeshift torch on the end of a bamboo pole. She was visible from clear across the farmyard, bent over a bench near the sink, working on something.

As I approached, I called out, “Your mom says an hour or two on the rabbit stew she’s making.”

“Good,” Darla replied. “That should be enough time to take care of this pelt. Would you bury the stuff in the offal bucket? Over where we put our crap.”

I glanced into the bucket. The intestines had been covered with a mass of jumbled rabbit bones. On top of it all was the rabbit’s skull. It had been violently crushed and wrenched apart, so it sat in two halves, like a discarded eggshell.

“Yipes, what happened to that?”

“What?”

“The skull.”

“Oh, I smashed it with a hammer and scooped the brains out with a spoon.”

“You what?”

“We need the brains to tan its pelt. I’ll show you when you get back.”

Dismissed, I picked up the offal bucket and a shovel. What kind of girl cuddles with a cute rabbit she named Buck one minute and the next smashes its skull with a hammer to scoop out its brains? I shivered—and only partly because of the cold night air.

I stumbled around in the dark, looking for the latrine area. I thought I had found it—it was impossible to be sure with everything covered in a featureless blanket of ash and no light except the faraway glint of the torch through the barn door. I buried the rabbit’s remains in a shallow hole and rejoined Darla in the barn.

She had tied the pelt into a small frame built of lumber; two-by-twos, she said. A dozen or so small cords, shoelaces maybe, stretched the pelt tightly in the center of the frame. Darla was scraping the skin with a rounded piece of metal.

“The brains are in there,” Darla said, gesturing at a bowl on the workbench beside her. “Pour a little water in with them—we want about half brains and half water. Then stir it up really well. It should look about like a strawberry milkshake when you’re done.”

“What?” Something about brains and milkshakes didn’t compute. Had I wandered into a bad zombie movie?

“We need a brain-and-water mixture about like a strawberry milkshake,” Darla repeated, talking very slowly, as if she were explaining to a preschooler.

“Why?”

“We’re supposed to use the mixture to tan the skin. After I get it scraped, we’ll rub the brains on it.”

“That’s kind of disgusting.”

“I guess. But it’s the traditional way to tan hides. There’s some kind of oil in the brain that soaks into the pelt and keeps it soft.”

“You do this a lot?”

“Nope, first time. Thought about trying it before, but never found the time. Some of the rabbit breeders I know do some tanning, and I’ve read up on it.”

I poured a little water in the bowl with the brains. They were gray, with little red streaks here and there. Blood vessels, I guessed. I found a spoon in the sink and used it to mash them up. It took a bit of stirring to get the mixture to the texture Darla wanted. When I finished, it looked almost exactly like a strawberry milkshake. Not that I was going to take a sip or anything.

Darla worked on the hide for almost an hour, scraping the inside clean. Then she put the frame flat on the workbench, the fur side of the pelt facing down. She poured some of the brain mixture onto the skin and rubbed it in with her hands.

I shuddered. She must have seen me, because she said, “It’s not bad. Feels a little oily. Like mayonnaise, sort of.”

I couldn’t let a girl show me up, especially not Darla, so I reached over and rubbed the hide as well. She was right; the brain mixture didn’t feel as gross I’d imagined it would. We rubbed it for ten minutes or so, trying to work the brain into every bit of the skin. It wasn’t a big pelt; our hands were constantly touching, sliding against and over each other, slick with rabbit brain.

Finally, Darla pronounced it done. We rinsed off our hands, pouring water for each other. Darla propped the frame against the wall and extinguished the torch, plunging us into darkness. I stood still, trying to let my eyes adjust, until I felt Darla’s hand in mine. She gave my hand a squeeze and then tugged on it, leading me out of the barn.

The warmth of her hand sent an ironic shiver racing up my arm. I knew that she didn’t like me much, that she saw me as a freeloader. I knew I should stay cool and detached. But I couldn’t help myself. No matter how much I told myself to chill out, it didn’t help. I wished we’d met before the eruption, when things were normal. Maybe then she would have seen me as something more than a helpless kid.

Darla dropped my hand, and I opened the kitchen door for her. It smelled intoxicating inside. Mrs. Edmunds ladled huge bowls of soup—she called it rabbit corn chowder—out of a pot bubbling on the stove. Darla began shoveling the soup into her mouth the moment the bowl touched the table in front of her.

“Darla!” Mrs. Edmunds exclaimed. “Manners.”

“Hurmm,” Darla replied, her mouth full of soup. But she quit eating.

Mrs. Edmunds put a cloth napkin and a glass of water at each place setting and took her seat at the head of the table. “Let us pray.” She laced her hands in her lap and looked down. “Lord, bless this food and those who eat it. Hold us safe in your loving hands as we struggle to meet the test you put before us. And remember especially those less fortunate than us, who don’t have enough to eat or the support of family and friends in this time of trial. Amen.”

Finally, I could eat. I’d never had rabbit, and before I had walked into the kitchen, I wasn’t sure how I felt about eating an animal that had been squirming in my hands only two hours before. But the heady aroma drifting out of the bowl drove all doubt from my mind. I dug in. It tasted even better than it smelled—a bit like chicken.

I wolfed down two huge bowls of stew. After dinner, we sat around the table talking for a while—mainly about plans for the next few days. I stifled the first few yawns that pushed up from my exhausted body, but eventually one escaped. Mrs. Edmunds shooed me off to my bed on the living room couch.

I was exhausted from the day’s work, my side hurt, and I’d overstuffed myself on chowder. I fell asleep almost before my head touched the pillow. I vaguely remembered someone checking my bandages that night, but that may have been a dream.

Chapter 22

The next two weeks passed in much the same way: work, work, and more work. I was anxious to get moving, to continue my quest to find my family. But I was still weak—it wouldn’t do me any good to start out again before I’d completely recovered. I knew I’d regret leaving Darla, but my family mattered more than some girl I’d just met and barely knew. And anyway, she seemed anxious for me to leave, too.

At least the work varied a little. Some things had to be done every day, like pumping water. We filled three five-gallon buckets each morning: one for the rabbits, one for the kitchen, and one for the bathroom. Darla told me the pump for the well had quit when the electricity went out, before the ashfall had even reached their farm. She’d rigged up a bamboo pole that protruded from the pump hole. I had to grab the pole and push it up and down fast to get water to flow out of a PVC pipe.

Wood had to be hauled to the living room fireplace every day as well, from a huge rick behind the house. We spent one day cutting more with a bow saw and ax. Well, mostly Darla cut and hauled the wood while I stacked it—my side was still too weak to do much of the heavy work. There was plenty of timber nearby: immediately around the house a bunch of trees grew, and there were more along a creek in the valley. Darla checked each tree before we cut it, bending a few twigs. If they were green and springy, we left the tree alone. But most of the trees were dead.

We spent the lion’s share of our time digging corn. We worked our way along the ridge where the ash was thinnest, pulling bag after bag of corn down the hill. Even then the work wasn’t done. The corn had to be shucked, scraped off the cob, and ground to meal. Darla had built a bicycle-powered grinder that I’d seen in action when I first arrived at the farm. Now I ground corn, endlessly it seemed, either pumping away on the bicycle or pouring the corn into the mill. I was starting to feel stronger, but Darla could drive the grinder at least twice as long as I could.

On my twelfth day on the farm, Darla cut the stitches out of my side. Droplets of blood welled up here and there when she pulled the threads from my flesh. Overall, the wound didn’t look too bad. But it was going to leave a heck of a scar.

The rabbits got sicker. We killed and skinned eight more—the ones Darla thought were so sick they wouldn’t survive much longer. That was too much meat to eat right away, so I helped Darla build a smokehouse. Helping Darla meant holding tools for her, scavenging nails, and cutting boards where she told me to, not to mention enduring abuse when I didn’t know which tool she meant or couldn’t cut a board straight enough to suit her razor-sharp eye.

We ripped up a chunk of the floor in the hayloft to get boards for the smokehouse. Darla said it didn’t matter since there wouldn’t be any more hay for years. It took the better part of a day for us to knock together a ramshackle structure about the size of a short outhouse, which seemed like a long time until I considered that we’d had to salvage all the materials and do the work without power tools. From then on, we had two fires to tend: one in the living room that we relied on for heat and a smaller one in the smokehouse.

We hung the rabbit meat on crossbars at the top of the structure where the smoke would pool. While we were building the first fire at the base of the smokehouse, I asked Darla, “So how long do we have to keep this fire going?”

“I don’t know exactly. Never done this before.”

“Like, a few hours?”

“No, days at least, a week maybe? I’ll probably leave the meat out here until we eat it—it’s cold enough that it shouldn’t spoil, even without the smoke.”

“How’d you know how to build this thing if you’ve never smoked meat before?”

“I saw a smokehouse once. Guy was using it to cure hams. And how hard can it be? Fire in the bottom, meat up top where all the smoke collects.”

“I guess.”

“I don’t know how it’s going to work for rabbit. Not much fat on them. Probably going to be pretty dry and tough when we get done smoking them.”

“Better than nothing.”

“Yep, it’ll beat not eating.”

Since I’d spent two days on the way here not eating, I had to agree with her. Almost anything beats starvation.

Chapter 23

The next day at breakfast, Darla proposed digging more corn. Mrs. Edmunds flatly refused. “Have either of you looked at the dirty clothes? If we throw one more thing on the pile, it’ll collapse the floor, and we’ll have to move to the barn.”

After Darla and I took care of the rabbits and fed the fires in the smokehouse and living room, we hauled water. Endless buckets of water, to fill the bathroom tub. Once we had it mostly full, Mrs. Edmunds tossed in the clothing, and we started scrubbing. Our clothes were so filthy, they quickly turned the water into a grayish sludge thick enough that Darla worried about it clogging the drainpipe.

We then had to wring out the clothing, rinse the tub, and refill it. Each refill required pumping six buckets of water, hauling the heavy pails across the yard, through the kitchen, and into the bathroom, and pouring them into the bathtub. We refilled that stupid tub five times before Mrs. Edmunds was satisfied that the clothes were “clean enough.” Then, of course, we had to wring the water out of the clothing and hang it on makeshift lines strung through the living room in front of the fireplace—the living room I’d been sleeping in. The damp clothes dripped onto the couch—my bed. I hoped it would dry before I turned in that evening.

After lunch, Mrs. Edmunds declared an afternoon of rest. She planned to read for a bit and maybe take a nap, she said. Darla frowned but didn’t reply. The nap bit sounded good to me.

It was not to be. As soon as Mrs. Edmunds settled into the easy chair with her paperback, Darla said, “Come give me a hand. I’ve got a project that’s perfect for this afternoon.” I sighed and followed her into the farmyard.

As usual, helping Darla mostly meant handing her tools. And, like when we built the smokehouse, I got yelled at whenever I didn’t know exactly what she was asking for or I couldn’t find it, which totally spoiled the good part of this project: watching her bend over the engine of the old F250 pickup parked beside the barn. The pickup was half-buried in drifted ash.

“Are we fixing it?” I asked.

Her voice came back muffled by the hood. “No, I don’t think I can. I drove it a bunch before the ash got too deep. The air filter is completely clogged, and I don’t have a spare. The ash probably tore up the engine, too. Might need a valve job.”

I didn’t know what a valve job was and wasn’t about to ask. Odds were, the answer wouldn’t make sense to me, anyway. “So why are we working on it?”

“I need the alternator. Gimme a medium ratchet with a half-inch hex head.”

I found the ratchet but couldn’t read the socket sizes in the crappy light. I put one that looked right on the ratchet and handed it to her.

She glanced at it. “That’s 15/32nds. Christ. Put on the next size bigger.”

I replaced the socket and handed it to her. “How can you even read the sizes?”

“Don’t need to. Honestly, any idiot could’ve seen that wasn’t a half inch.”

“Well, I couldn’t.” I raised my voice a bit and shot clipped words at her. “And I’m not an idiot. And this is getting old. I know you’ve probably got ash in your panties, but do you have to take it out on me?”

She pushed herself out from under the hood. “Huh? What did you—”

“Ash in your—well, you seem so irritated at me all the time.”

“Ash in my—” She laughed. “Yeah, I do. And it is irritating. And what are you doing thinking about my panties, anyway?”

I blushed, hoping the inevitable layer of ash on my face hid it. “Uh, sorry. But seriously, it’s not my fault I wound up here. And I’ll be moving on soon. I feel tons better already.”

“Good. Maybe I have been bitchy, but having you around hasn’t exactly been easy for me. Mom thinks we can take in all the world’s strays, but who knows how long this will last? We might still be eating cornmeal a year from now—or three.”

“Yeah, I understand. I won’t hang around. I need to find my own family.”

“And when you go, don’t take all our supplies. I know Mom, she’ll try to convince you to stay, and failing that, she’ll load you down with more of our food than you can possibly carry.”

“I won’t.”

“I guess you’re entitled to some of it . . . .You’ve been working pretty hard, considering that hole in your side.” Darla buried her head back under the truck’s hood. “Gimme a big flathead screwdriver.”

I found one and slapped it in her outstretched hand. Maybe it was my imagination, but it seemed as though her fingers lingered against mine a bit longer than necessary to take the screwdriver. Could the frozen shell she kept between us be thawing just a little?

We pulled the alternator out of the truck and carried it to the barn. Darla bolted it to a workbench. Then she welded a bicycle gear onto the disc on the side of the alternator. She had a welding setup that ran off two metal cylinders that looked like helium tanks. When that was finished, she disconnected the bicycle we’d been using to drive the grain grinder and connected it to the alternator with a long chain. She attached the alternator wires to a battery charger, the kind that held eight D-cells.

Meanwhile, I’d been doing nothing useful. Handing her a tool now and then, but mostly watching her work. She checked the tension on the chain, made an adjustment, and said, “Your turn to work. Get on your bike and ride.” Darla grinned. “I think I just quoted some band Mom likes.”

I climbed on the bike and started to pedal. It was easier than driving the gristmill—there was a lot less resistance. As I got the bike up to speed, a red light began glowing on the battery charger, lurid in the dimness of the barn.

“When that light changes to green, we’re done,” Darla said.

I pedaled away in silence, listening to the sound of my breathing grow louder and more labored as I rode. Each time I slowed a little, Darla snapped, “Faster!” or “Pedal harder!” I kept it up for a long time, maybe an hour or so, before she finally offered to relieve me. I might have gotten annoyed at her bossiness, but I was too tired to care.

I collapsed onto the dirty straw on the barn floor, utterly spent, as Darla mounted the bike and pumped the pedals. We traded off twice more, riding the bike at least three hours before that stupid light finally winked green.

By then, I was exhausted and hungry, and Darla wasn’t looking too perky, either. She pulled the batteries out of the charger and put them in her jacket pockets. We trudged to the house to wash up for dinner. I was surprised at how sweaty I’d gotten despite the cold air.

After dinner, all three of us sat around the fire in the living room while Darla fiddled with an old radio. Mostly we listened to static. My legs had paid dearly for that static: They ached. I reached down to rub my calves—it felt like rubbing tires, they were so tight.

Low on the AM dial, Darla finally got something. A couple of stations drifted in and out, frequencies changing slightly, as if the vagaries of the ash-laden atmosphere were somehow distorting them. One of them was playing music, of all the useless things they could do. Peppy, annoying, big band music, the kind my great-grandmother might have listened to on the radio. It baffled me why they were playing it now.

Another station was more helpful. They read nonstop news—all of it related to the eruption. The maddening bit was that we could only make out little snatches of news over the static as Darla chased the station around the dial. She caught it the first time at 590 AM, but it would drift as high as 640 and as low as 570 at times.

The first snatch of news was, “. . . In addition, the Admiral announced that a U.S. Navy relief convoy will dock at Port Hueneme in Oxnard, California, sometime tomorrow. While most supplies are designated for federal refugee camps in northeastern California, some food, medical supplies, and tents will be available to citizens through their local interim authority.

“Admiral McThune went on to say that a third Chinese humanitarian mission has been granted permission to land in Coos Bay, Oregon, joining the previous two in Newport and . . .”

“Damn. Lost it,” Darla said.

“Watch your mouth, young lady,” Mrs. Edmunds scolded.

Darla fiddled with the radio, looking for a signal.

“How big is this thing?” I asked. “If Oregon and California are as bad off as Iowa . . . how long will it take to get any help here?”

“Let’s see.” Mrs. Edmunds pulled an old Rand McNally road atlas off the shelf. Near the front there was a yellow map of the U.S. cross-hatched by blue interstates. Judging by the map, Oregon and Northern California were both closer to Yellowstone than we were.

The room was quiet except for the hiss and crackle of the radio and an occasional pop from the wood burning in the fireplace. I thought about all the people facing this disaster—the millions between me and the Oregon coast. Millions of them must have already died. I’d been incredibly lucky to survive this long. Darla and her mom were doing okay, digging and grinding corn, but most people wouldn’t have access to fields of buried corn or know how to improvise a grinding machine. Millions more people would die unless some kind of help arrived soon.

Darla found the station again. “Responding to critics,” he said, “the suspension of civil liberties contained in the Federal Emergency Recovery and Restoration of Order Act is temporary and will be lifted as soon as the crisis has passed, perhaps as early as late next year.’

“The vice president concluded his remarks with strong words for ‘those nations whose hoarding and profiteering caused the collapse of the international grain markets.’ He pledged to use the full force of the United States to insure an equitable . . .”

None of us were sure what to make of that. It didn’t sound good, but it also didn’t seem to affect us much. The only functioning government I’d seen since the disaster was Mr. Kloptsky’s at Cedar Falls High. And our grain market consisted of the corn we could dig up in a day.

We listened to the radio until the batteries died late that evening, but we only caught one more intelligible fragment: “. . . announced earlier today that, using the emergency powers granted it under FERROA, the Department of Homeland Security has appropriated a large tract of land near Barlow, Kentucky, to control the influx of refugees from southern Missouri. Construction will begin . . .”

This was more interesting. We found Barlow on the Kentucky page of the atlas. It took some searching—it was a tiny black speck of a town near the Mississippi River. Nowhere near us, but at least on the same side of the country.

“Maybe there’s help east of us,” I said.

“Sounds like there must be,” Mrs. Edmunds said.

“I need to leave soon.” I said it with some regret. I would miss Mrs. Edmunds. And I’d miss Darla.

“You’re welcome to stay. You’ve worked so hard—more than earned your keep.”

“Thanks. I . . .” A thought seized my brain: I’d be dead if not for them. I fought back tears. “I don’t know how to thank—”

“Shush,” Mrs. Edmunds said. “Anyone would have taken you in. Why, you were half-dead when you fell into our barn.”

Actually, anyone wouldn’t have taken me in. I’d met people who wouldn’t. The faceless person who’d pointed a rifle at me as I skied toward his farmhouse, for one. Target, for another. I shuddered at that memory. “I wish we’d heard more about what’s going on in Illinois.”

“Your family is there, right?” Mrs. Edmunds asked.

“Yeah . . . at least, that’s where they were headed.”

“Maybe someone in town would know more.”

“I’ve been thinking about going to town, anyway,” Darla said. “I need to ask Doc Smith about my rabbits. I’d feel better if I could save a few of them to breed.”