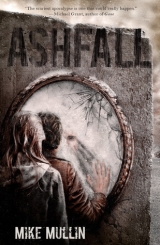

Текст книги "Ashfall"

Автор книги: Mike Mullin

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Chapter 52

We plodded along the road, walking next to the snow berm on the left. It was much easier—we were probably going three or four times faster than we had been through the snow. Despite the faster pace, I could almost keep up.

“If we hear a car or see headlights, dive over the snow berm and hide,” Darla said.

“They’ll see our tracks.”

“Maybe not—it’s dark, and hopefully they’ll be moving fast.”

I grunted.

We hadn’t been walking long when we came to an intersection. The road we’d been following teed into a highway. A road sign poked out of the snow on the far side of the intersection, but it was so dark we had to walk right up to it to read it: W. Heller Lane and Stagecoach Trail.

“Good call on the left turn back there,” Darla said with a smile I could barely make out in the darkness.

“Lucky, for once.”

We turned right on Stagecoach Trail. Maybe it had started as a trail years ago, but now it was a plowed highway. We followed the same strategy, walking on the left side of the highway along the berm, ready to dive over it if we heard anything coming.

The road was deserted all night. I dragged my feet along in a fugue state, not thinking anything, trying not to feel anything: right foot, left foot, right foot, left foot.

Not long after dawn we passed over a bridge. A sign that barely protruded from the snow berm read: West Fork Apple River. I told Darla we were close, although I couldn’t remember exactly how much farther we had to go.

An hour or so later I woke to Darla shaking my shoulder. “Get up. Get up!” I looked around woozily—I was lying in the road. “Goddamn it, Alex, get up and walk!”

“What happened?”

“I looked behind me, and you were fifty feet back, taking a nap.”

“Sorry.” I struggled to my knees. Darla knelt beside me and tucked her head under my arm. Leaning on her, I found I could stand. After that, we hobbled down the road with my arm over her shoulders.

Sometime later, we heard the noise of an engine approaching behind us. Darla dragged me toward the berm. We were still trying to thrash our way over the snow pile when a car whizzed past.

The next time we heard a car engine, we didn’t even bother trying to hide. There was no sign of Black Lake; if we were lucky, they were busy chasing refugees closer to the camp.

I found I could close my eyes and keep moving, stealing a sleepwalking nap with my arm draped across Darla’s shoulders.

Ages later, I woke from one of those semiconscious snoozes. “Alex, hey, you in there?” Darla asked. “We’re close, check it out.” I cracked open my eyes and looked around. There was a graveyard on the left side of the road, with a sign: Elmwood Cemetery. I could see the buildings of Warren ahead.

“Canyon Park,” I mumbled.

“What?”

“Think we went too far. Supposed to turn south on Canyon Park Road.”

“We passed that an hour ago. I think you sleepwalked through it.”

“Ugh. Turn around. Sorry.” I was too tired even to feel upset with myself over the extra hour of walking.

Darla must have felt the same way, because she didn’t say anything. She just wheeled us around, and we crossed the road, walking on the other side back in the direction we’d come. I fought to stay awake, to spot the turnoff we’d missed. “Left here,” I said. “It’s close. Less than five minutes in a car.”

Canyon Park Road was plowed, which surprised me. I remembered it as a little-used dirt road. The prospect of ending my journey brought out some hidden reserve of energy within me. I leaned less on Darla and picked up the pace some. My mother, father, and sister might be only a few hundred yards down this remote lane.

We’d walked about a half-hour when I saw the front of my uncle’s long driveway. It wasn’t plowed, but someone had shoveled a path in the snow. The light wasn’t bad; it was early afternoon, so when we got closer I could make out his house at the end of the driveway. The barn and duck coop were still standing, and there were two other structures, long half-cylinders constructed of wood and plastic sheeting. Greenhouses, I remembered. Darla and I turned up the driveway, walking in the shoveled path.

We’d traversed maybe half the driveway when we heard a faint noise from inside the house. A drape was thrown open, and I saw my uncle looking through the window, holding a long gun against his chest. Then I heard a high-pitched shout. The front door was flung open, and my sister tore down the driveway toward us.

“Alex! Alex!” she screamed. She ran pell-mell into my arms, knocking me backward into the snow. “You’re alive! You’re alive—”

“Good to see you, too, Sis.” I didn’t know if she was laughing or crying or some mixture of the two. I wanted to do both, but I couldn’t summon the energy. So I just hugged her close and looked over her shoulder.

Uncle Paul, Aunt Caroline, and my cousins, Max and Anna, were all standing around us now. Everyone looked thinner and older than I remembered. I scanned the faces again, looking for my parents.

“Where’s Mom and Dad?” I said.

My sister’s laughter ended abruptly. She didn’t reply.

“Where’s Mom, Rebecca?”

“They’re . . .”

“They’re what?”

“They’re gone, Alex. They’re both gone.”

Chapter 53

I woke in a bed, confused. It was sublimely soft, made up with old cotton sheets conditioned by hundreds of washings to near-perfect comfort. A heavy bedspread lay over the top. Despite my uncertainty about how I’d gotten there, I felt warm and safe for the first time since I’d left Cedar Falls.

Darla was slumped in a chair beside the bed, napping. Her head was completely bald.

“Darla . . .” I said. “You awake?” The question didn’t really make sense. She was asleep—I was trying to wake her.

“Uh?”

“You in there?”

“Yeah.” She stretched her arms and yawned. “You scared me. Just folded up right there in the snow.” “I don’t remember.”

“I don’t know if it was starvation, exhaustion, or what, but you passed out. How are you feeling?”

“Okay. Hungry and thirsty. Sore. How long have I been out?”

“I dunno. Not sure how long I’ve been asleep.” Darla walked to the window and pulled the curtain aside. “It’s getting dark. Guess we’ve been asleep all afternoon.”

“What happened to your hair?”

“Bald is beautiful, huh?” Her tone of voice didn’t suggest she found it particularly beautiful.

I shrugged.

“Well, you look pretty odd without your hair, too.”

I touched my head. Sure enough, my hair had all been shaved off. “What? Why?”

“Lice. We were lousy with them, ha ha.” She didn’t sound the least bit amused. “They don’t have any pesticide shampoo, so . . .”

“It doesn’t look so bad. And it’ll grow back.”

“I guess.”

I put my hand out from under the covers and held hers. My hand was a shocking white—the layer of grime and ash had been scrubbed off. It was hard to believe I’d slept through being washed and having my head shaved; I must have been deeply unconscious. Darla and I sat in silence for a minute or so until I remembered what my sister had been saying before I passed out.

“My parents. Are they—”

“I’d better get your uncle to explain. He’s been . . . weird.” Darla dropped my hand and stood up. “I’ll be right back,” she said as she left the room.

Not sixty seconds later, my uncle came in with Darla following. He turned, looked at her, and cleared his throat. They stared at each other a moment.

“I’ll be in the kitchen,” Darla said, then left the room again.

“Who is she?” Uncle Paul asked.

“What happened to my parents?” I said.

“She said you met in Worthington? How well do you know her?”

I pushed myself up in the bed with some effort. The covers fell away from my torso. Blood rushed from my head, and I felt a bit woozy. “I wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for her. She saved my life. More than once.” I stared into my uncle’s eyes, making an effort not to blink. “I’d die for her.”

Uncle Paul looked away. “Heck of a scar on your side.”

“Darla stitched it.”

“She didn’t tell us about all that. I guess we can count on her, then.”

“You can.”

“I’m sorry. It’s . . . there’s all sorts of crazies out. Don’t see much of them here, but we hear stories. Folks who live out on Highway 20 have had a rough time.”

“Tell me about it. . . . Where are Mom and Dad? Are they dead?”

“Yes. That. I tried to talk them out of it, but they were determined.”

“Out of what? And quit dodging the question. Are they dead?”

“I don’t know. They left five weeks ago. They went back to Iowa.”

My chest felt suddenly heavy. “Why? And why’d they leave Rebecca here?”

“They went to look for you.”

“They what?”

“They went into the red zone to find you, Alex. We haven’t heard any news of them since they left.”

“Crap.” I swung my legs out of the bed, realized I was naked, and pulled a corner of the covers over my lap. I’d spent the last eight weeks struggling to reach my uncle’s farm, figuring that once I got here my quest would be complete. But it wasn’t. Sure, I’d be safe here, but if I were only looking for a safe place to stay, I never would have left Mrs. Nance’s school in Worthington. “I’ve got to go back. Try to find them.” I looked around for my clothing but didn’t see it.

“No. You’re safe here—”

“But they’re not safe in Iowa. They’ve got no idea what they’re getting into.”

“They had some idea before they left. Things have been rough here, too. I traded a pair of breeding goats for a shotgun and gave it to your dad.”

“My dad? With a shotgun? No way. He’s liable to hurt himself.”

“People have changed. Your dad’s not the same man he was. Heck, you’re not the same either—I don’t see any sign of the sullen kid who used to bury his nose in a computer game or book the moment he got here.”

“Yeah, well.” I didn’t care much for being called a sullen kid. But maybe he was right. I had changed. “I should go back. I know what to expect in Iowa now. They might need help. I didn’t even leave a note at the house, and my bedroom is completely collapsed. There was a fire, too. If they get there, they might think I’m dead. I guess Darren and Joe know I was alive when I left, but they might be dead or gone by now.”

“If they can’t find you, they’ll come back here for Rebecca. If you go, how will you find them? You’ve already passed each other on the road. And this winter is only going to get worse. All the ash and sulfur dioxide in the air is going to wreck the weather for years. It’s going to get colder and harder to travel—”

“With skis I can—”

“You might need skis just to travel next summer. The volcanic winter might last a decade, nobody knows for sure.”

A decade of winter? That hit hard. How would anyone survive?

“Just wait, Alex. Maybe they’ll come back. If they haven’t shown up next summer, maybe conditions will be better so you can go look for them. Maybe by then FEMA will be in Iowa.”

“Huh. That’d hurt more than it’d help.”

“At least they clear the roads and maintain some order.”

“You haven’t done time in a FEMA camp.” My face was tense, scowling.

“No. But there’s another reason you shouldn’t take off after your folks. You’re needed here. I need your help. We could be looking at years without a reliable food source. We need to stockpile corn and wood, build more greenhouses, and figure out some way to keep feeding the goats and ducks. There’s an immense amount of work to be done.”

I nodded grudgingly. “Okay. I’ll think about it. But if Mom and Dad haven’t shown up by next spring, I’m going to go look for them. In the meantime, I’ll help—although Darla will be way more helpful than me. She was running a farm practically alone when we met.”

“Let’s not make any decisions today. It may be summer before the weather improves—if it does at all. But okay. If we can get things on a solid footing here, I’ll consider supplying you for an expedition back to Cedar Falls.”

“Where’s my clothing?”

“It was infested with lice. We hung it in a corner of the barn. I’m thinking the lice might die eventually if there’s no one for them to feed on. I’m not sure.”

“Yuck.” I felt itchy all over.

“I’ll get some of mine for you. Come down to the kitchen when you’re dressed; it’s dinnertime.”

Chapter 54

My cousins Max and Anna, my sister, and my uncle were sitting at the table in the kitchen. I saw Aunt Caroline and Darla through a window, cooking over a fire outside.

The table was already set. I sat down and drained the glass of water in front of me in a few gulps.

“Jugs on the counter are drinking water,” Uncle Paul said. “Help yourself if you want more.”

I got up and refilled my glass. While I was up, Darla came through the back door carrying a frying pan and a plate stacked high with omelets. Aunt Caroline followed, hefting a plate of cornbread.

It was an odd dinner, but by far the best meal I’d eaten in weeks. The cornbread was real—not corn pone. The omelet was delicious, but it didn’t taste quite like any omelet I’d ever eaten. The stuffing was some purplish leaf I couldn’t identify, and the eggs and cheese tasted weird—not bad, but different. I asked Aunt Caroline about it.

“It’s a duck-egg, goat-cheese, and kale omelet,” she replied.

“The ducks are mine,” Anna said, grinning proudly.

“I don’t know how long we’ll be able to keep the ducks,” Uncle Paul said. Anna glared at him, but he continued, “Or the goats, for that matter. We’re going to run out of hay.”

“How’d you keep them alive through the ashfall?” Darla asked.

“We didn’t—not as well as I’d have liked, anyway. We lost four ducks and two goats to silicosis. But when we figured out what was going on, we started keeping them in the barn all the time and spreading wet straw to keep the dust down.”

“Where’d the kale come from?” I asked.

“We planted a fall garden in our greenhouses, before the eruption. But it got cold so fast that only the kale survived. We’ve been feeding the dead cucumber vines, tomato plants, and so on to the goats, but we’re out of those now. We’ve replanted—mostly kale, so I hope you like it.”

“Tastes fine to me,” I said.

“Your taste buds need tuning up,” Max said grumpily, although he was eating his kale omelet, too.

“Tell us about your trip,” Uncle Paul said. “From the little bit Darla’s told us, you had a rough time.”

“I don’t really want to talk about it,” I said. That wasn’t exactly true. I didn’t even want to think about it, much less talk.

“That bad, huh?”

“Yeah.”

I hoped he’d drop it, change the subject or something, but he kept asking questions. So I slowly released the breath I’d been holding in and relented. For the rest of the dinner and a couple of hours afterward, I told them my story. Darla pitched in some after I got to the part where I had met her. I paused before I told them about Darla’s mom being raped and murdered. I wasn’t sure how much I should say with Anna, Max, and my sister there. Anna and Max were ten and twelve, or maybe eleven and thirteen—I wasn’t sure. My sister would be fourteen next month. I asked Uncle Paul, “How much of this do you want me to talk about with your kids here? What happened when we got back from Worthington, it was . . . obscene. I’m not sure I even want my sister to hear this.”

Paul and Caroline glanced at each other. He said, “Go on. They need to know about the world they live in now.”

“Anna might get nightmares,” Caroline said.

Paul turned to Anna, “Do you want to stay? You don’t have to listen if you don’t want to.”

“I’ll stay,” she said.

So I told the whole story to everyone. Still, I tried to gloss over the worst parts of it. Darla certainly didn’t need to relive that day. I took her hand and squeezed it, offering whatever meager support I could.

When I finished talking, Rebecca was staring at me, her head tilted at a slight angle.

“What?” I asked.

“I can’t believe you did all that. I always knew that you were, like, tougher than you seemed, but—”

“I wouldn’t have survived without Darla.”

Rebecca turned her gaze on Darla. They looked at each other for a moment; then my sister nodded, and Darla smiled a little. I wasn’t sure what to make of the exchange. Somehow during the last eight weeks my exuberant, chatty sister had been replaced by this thoughtful alien who could communicate with a look what would have taken the old Rebecca an hour’s worth of words.

“We’d best get to bed,” Uncle Paul said. “There’s more corn to grind and wood to cut tomorrow.”

“Where do you want us to sleep?” I asked.

“You can bunk with Max. Darla and Rebecca will have to share the guest room—the room you were in when you woke up.”

Max and Anna erupted into simultaneous protests.

Max: “Why do I have to share my room? Why does Anna get her own?”

Anna: “How come I don’t get a roommate? Why does Max always get everything?”

Aunt Caroline overrode them both. “Anna, I want you to find the air mattress. I think it’s in the linen closet. Max, come with me. I’ll help you shovel out some space for Alex in that pigsty you sleep in.”

Darla grabbed my arm and whispered, “Alex, I’d rather if we slept—”

“I’ll talk to him.”

She nodded.

Uncle Paul got up from his chair. I looked at him. “Uh, can I talk to you?”

“Sure.” He sat back down.

My sister was still at the table. I made a get-out-of-here gesture with my head. She didn’t move. “In private?” I said. “Please?”

“Oh. Yeah.” Rebecca and Darla left the kitchen.

“Um . . .” I thought furiously. How should I start? “Darla and I have been together for six weeks now.”

“An eternity in the life cycle of the American teenager.” Uncle Paul smiled, not unkindly.

“Darla’s almost eighteen, and I don’t really think of myself as a teenager anymore.”

“You’ve been through stuff no teenager should ever have to face, that’s true. But you’re still a minor, Alex.”

“I know, but . . .” This wasn’t going the way I’d hoped. “Look, Darla and I have been sleeping together—”

“Exactly how should I take that? Is there a chance she’s pregnant? Do you have any idea how risky that could be, how often women and their babies died in childbirth before we had modern medical care? Which we don’t have right now.”

My cheeks burned. I’d tried, unsuccessfully, to break in between each of those rapid-fire questions. Now he took a breath, and I said, “When I said sleeping together, that’s exactly what I meant. There’s no chance she’s pregnant. Even if it were perfectly safe, the last thing we want is to bring a baby into this mess.”

“That’s a relief.”

“I feel safe with Darla. She’s the reason I’m alive.”

“And we’re grateful—”

“Anna wants a roommate. Max doesn’t. Why don’t we move my sister in with Anna, and Darla and I will take the guest room?”

“What I was going to say was, we’re grateful to Darla for getting you here in one piece. And I’m sure she’ll be a big help. But you’re both minors. Until your parents return, you have to live by the rules Caroline and I set.”

“Which is why I’m asking—”

“You’ve only known each other six weeks. I know it seems intense to you now, and you’re sure you’ll love her forever, but things change when you’re young. You’re too young to be making permanent decisions—and too young to be sharing a room.”

“But—”

“Final answer, sorry. When your folks get back you can revisit it with them.”

A hot wave of anger washed through me. My muscles tensed. I sucked in a deep breath and fought down the anger. Several retorts occurred to me, but none of them would have helped my case. From his perspective, it made sense—maybe. He saw me as the quiet, angry kid who used to visit his farm under duress. The kid I’d left behind in Worthington—along with a couple quarts of my blood.

“Okay,” I said.

Paul stared—his lips parted, and he tilted his head to the side.

“I don’t like it, but you’re right about one thing. It’s your house and your rules. You see me as a kid—”

“I know you’ve changed.”

“We’ll live with it for now. But eighteen is only a number. The magic number could just as easily be—has been, for other societies and other times—thirteen or sixteen or twenty-one.”

“True enough.”

“You’re going to need all of us to act like adults to get through this.”

My uncle nodded. “It’s one of the things that bothers Caroline and me most. What kind of childhood can the kids have in the midst of this chaos? A few chores, the responsibility of caring for the animals—those things have always been good for them. But now we’re all working dusk to dawn, trying to prepare for the long winter.”

“Darla’s spent the last few years working every waking minute to keep her farm going. She turned out okay. The kids could do worse.”

“Yes. But I still feel guilty. I should be sending them to school every morning, not into the fields to dig for corn.”

I shrugged. “There’ll be time for school when things get better.”

“I hope so. I’m off to bed. Goodnight.”

“Goodnight.” I scowled at his back as he left. I’d done the best I could, stayed calm, and made a solid rational argument, but what good had it done me?

I walked to the guest room at one end of the first floor and knocked on the door. Darla opened it dressed in an oversized T-shirt—one of Caroline’s, I figured.

“How’d it go?” she asked, closing the bedroom door behind her.

“Not so good. We’re kids, we haven’t known each other long enough, we’ll fall out of love, we’re both minors, oh my God don’t get her pregnant, and it’s my house and my rules.”

“That bad, huh?”

“Yeah. The problem with adults is that they always see you in the crib you slept in as a baby. The one with the bars on the sides. I was hoping Uncle Paul might see things differently.”

“He will.”

“I’ve got half a mind to go back to Iowa to look for my parents.”

“I’m not sure how we’d find them.”

“I’d go back to Cedar Falls. Maybe they’ve been to the house.” Then I thought about what she’d said. “We . . .?”

“You didn’t think I’d let you go back to Iowa alone, did you?”

“Uh—”

“I’m not sure I trust you to walk from here to the barn without hurting yourself, let alone all the way to Cedar Falls.”

It sounded mean, but Darla was smiling as she said it, so I forgave her. “You’re right—we might not be able to find them. And the weather is probably going to get worse. The smart thing to do is to wait here.”

“Doing nothing is tough, even when it’s the right choice.”

“It’s more than that. During the trip, I was free. In Cedar Falls or here, I’m just somebody’s kid. In between, I was Alex. I decided where I slept and when, who I talked to and who I avoided. Sure, the ash and psychotic killers weren’t fun, but I’ve only been here one day, and already I miss that feeling of freedom, of being my own man.”

“Your uncle will figure out that you’re not a kid. Give him some time to stop remembering the old Alex and start seeing who you are now.”

“I hope you’re right. And thanks.”

I wrapped an arm around her waist and kissed her. We stood in the hall and made out until Aunt Caroline’s voice wafted down the stairs, telling me my bed was ready. Darla said goodnight, and I clomped up to Max’s room.