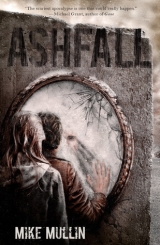

Текст книги "Ashfall"

Автор книги: Mike Mullin

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

“Roll over.”

I did. Darla’s lips were on mine before I’d completely turned over. We kissed. I felt like I was falling, plunging headlong down a warm, moist tunnel.

My eyes were closed. My right arm was wrapped around her shoulder; my hand gently cupped the back of her head, as if it were some wondrous glass sculpture, fragile in my palm.

Darla started crying.

No, that’s wrong. She wasn’t crying; she was sobbing, in full-throated wails. I pulled away, shocked. What had I done wrong?

Darla wrapped her arms around me, pulling my body back to hers as she cried. She held on as if she were trying to crush my body in her arms. I returned her embrace a little weakly—I was having trouble breathing.

When she’d finally run out of tears, her arms relaxed, and I sucked in a deep breath.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “That kiss. It was . . . how can we feel so good when so many people are dying? I started thinking about Mom, Dad . . .”

She was quiet. I held her tighter.

We lay like that for a long time, but eventually it got uncomfortable. Our knees knocked together. Darla rolled over again, and I snuggled against her back.

Her breathing calmed as she drifted to sleep. I watched the firelight play with her hair, watched it until the fire had burned so low that I couldn’t see her anymore. Then, at last, I slept too.

Chapter 36

After breakfast the next morning, we thoroughly searched the house. We both thought there must be more bullets somewhere—what use is a gun with only one bullet, anyway? But we couldn’t find any.

We did find clothing: hats, gloves, scarves, heavy flannel shirts, and even an insulated pair of overalls. By mixing and matching the new stuff with what we already had, we managed to put together two decent sets of winter gear.

There was no food at all in the house. The refrigerator stood open and empty except for a box of baking soda. We found two candles in the kitchen, fat pillars of the sort that would be annoying to carry in our pack. Darla borrowed my knife and gave them impromptu liposuction, whittling the excess wax off the sides.

I found a ball of string in one of the kitchen drawers, but Darla said it wasn’t heavy enough. She wanted something tougher to fix my ski poles, so we explored the barn.

A snowdrift had covered the long side of the barn, reaching upward almost to the eaves, which made it something like fifteen feet deep. We skied around, looking for a way in.

There were no doors on the right side or back of the barn. When we got to the left side, we found a big square hatch set on the inside of the jamb so it would open inward. Darla said it was for unloading manure, but I didn’t know how she could tell. There was no sign or smell of manure there.

I tried the hatch; it was locked. But it had a little wiggle to it on the right side, like it was loose. I took off my skis and kicked the door with a simple front kick. I got my hips behind the kick, thrusting forward for extra power, like I would for a board break in taekwondo. The door rattled, but the latch didn’t break. I tried again. On the third try it finally gave, and the door flew open with a bang.

I stepped into the barn. The door had been secured from the inside with a simple hook and eye. My kick had ripped the hook out of the doorframe.

“Damn,” Darla said appreciatively, looking at the splintered spot in the wood.

I shrugged. We broke boards all the time at the dojang. It was no big deal.

In the barn’s loft, we found fifty or sixty bales of hay—the small, rectangular kind.

“Perfect,” Darla declared.

“We need hay?”

“No, silly, the baling twine—I can make ski pole baskets with that.”

So I cut twine off the hay bales while Darla searched for some wood. We carried everything back to the living room and built up the fire.

Darla whittled a shallow groove into both my poles about five inches from the bottoms, using my mother’s mini-chef’s knife. She cleaned off the bark from two sticks and cut them about eight inches long. Then she lashed the sticks to one of the poles in an X shape, wrapping twine in the groove so the sticks couldn’t slide up or down.

I handed her stuff and cut twine for her. She talked while she worked. “This reminds me of working with my dad. He used to let me do everything—well, everything I was strong enough for. He’d hand me tools and tell me what to do with them. I’d usually screw it up, at least the first time, but he’d just tell me what I was doing wrong and let me try again.”

“What’d you guys work on?”

“All kinds of stuff. We built a hydraulic tree-digger when I was ten or eleven. Big thing with four blades on it that you could hook up to the tractor and use to move live trees around. That’s when he taught me how to weld.”

“You learned to weld when you were ten?”

“Yeah. Why?”

“I don’t think I was allowed to touch the stove when I was ten, let alone use a welder.”

“Yeah, well. With your amazing mechanical aptitude, I wouldn’t have let you touch a stove, either.”

I might have taken offense, but she was smiling at me in a way that made it impossible to be mad. “Why’d you want to learn all that stuff?”

“I dunno. I’ve always been interested in machines. And Dad was a great teacher. He’d smile when I got to the barn after school. He had the most amazing smile—it lit up his whole face. Then he’d turn everything over to me, show me where the project was at. It was probably a lot slower than doing it himself, but he never once complained. We did everything together—fixed the tractor, mended fences, built stuff . . .”

“It must have been hard when he died.” The moment I said it I realized how stupid it sounded. Duh. But Darla didn’t seem to mind.

“Yeah. I tried to keep the farm going. At first the neighbors came by all the time to help. But that didn’t last long.”

“The farm? I thought you only had the rabbits.”

“You didn’t think all that corn we were digging up planted itself, did you?”

“You did all that?”

“Yeah. Got crappy grades at school. Kept falling asleep in class. Almost had to repeat sophomore year.” Darla frowned. “It got better junior year. Mom and I sold off the cows and leased out some of our land, so it wasn’t as hard to keep up.”

“Junior year . . . how old are you?”

“I’ll be eighteen in February. You?”

“Um, I dunno.”

“What do you mean, you don’t know?”

“What’s the date today?”

Darla thought for a few seconds. “It’s the fourth of October.”

“I guess I’m sixteen then. My birthday was two days ago.”

“Wow, missed your own birthday.”

I shrugged. “So . . . I’ve fallen for an older woman? You going to take me to prom?”

“Yeah, right. Even if there was a prom, I probably wouldn’t be going. Probably be too busy.”

“So much for the benefits of dating an older woman.”

“Happy birthday.” She leaned over and kissed me, a quick peck on the lips. I hoped we’d keep kissing, but Darla returned to working on my ski poles. She tied a series of strings connecting the crossbars so that when she was finished they looked like diamond-shaped dream catchers.

When Darla finished she said, “Ta-da! New ski poles. For your birthday. Not much of a present, I know, but it’s all I’ve got.”

“When you followed me out of Worthington, that was my real birthday present.”

* * *

The poles worked great. The combination of crossbars and string grabbed in the snow, so my poles only sank a few inches. It didn’t do anything for my skis, of course. They still had an annoying tendency to dive under the powder instead of gliding on top of it, but if I stayed in Darla’s tracks, we made progress.

Early that afternoon we came to an intersection. A wide road crossed our path. A sign poked about a foot above the snow. Darla knocked the ice off it: U.S. 151.

That startled me a little. The snow on 151 was completely undisturbed—no one had used it since the blizzard had ended. Shouldn’t a major highway have had some kind of traffic? People walking along it, at least? Was everyone dead? The east-west road we’d been on for a while, Simon Road, had been deserted as well, but it was a minor county lane, probably not even paved.

“Highway 151 goes to Dubuque,” Darla said. “We should head north.”

“I dunno. Didn’t Mrs. Nance say there’d been riots in Dubuque?”

“The only bridges across the Mississippi within thirty miles of here are in Dubuque.”

“Crap. Okay.” We turned north.

* * *

Two hours later, we still hadn’t seen signs of anyone on the road. We passed two farmsteads that had tracks in their yards, and two more that appeared to be deserted, but it was too early to stop for the night.

Every now and then we passed a big rectangular shape covered in snow. I asked Darla what she thought they were.

“Abandoned cars,” she replied. “Buried in ash and snow.” That made sense—why hadn’t I thought of that?

We hurled ourselves up a ridge, duck walking. At the top, a glorious downhill slope stretched out below us. Darla grinned and pushed off. I carefully fitted my skis into her tracks and shoved hard with my poles, racing to catch up. We flew down the slope, wind burning our cheeks, freezing air filling our nostrils. Darla laughed, and I let out a whoop.

About halfway down, Darla stood up on her skis and quit pushing with her poles. I started to yell, to ask what was wrong, but she held up a hand, motioning for quiet. That didn’t make sense until I caught a glimpse of what lay ahead of her.

Someone was coming up the road toward us.

Chapter 37

Neither of us was much of an expert in cross-country skiing. I didn’t think I could stop myself on the downhill slope without falling over. Anyway, Darla was in the lead and had a better view of the approaching people, so I left it up to her. She kept going, and I followed.

As we got closer, I could see them better. A woman plodded toward us through the deep snow. She was bent almost double, straining against a rope looped around her waist. The rope led to a toboggan. There was a suitcase at the front—a big black one with wheels on it, the type that people used to drag through airports. Three kids sat behind it.

The two kids near the front of the toboggan were tiny, maybe two and four years old. They were bundled up tightly in hats, gloves, and warm-looking snowsuits. A larger girl, maybe six or seven, rode at the back. She had on a good snowsuit, too, but no hat and only one glove. Her head lolled to one side, long blonde hair whipped by the wind. Her gloveless right hand dragged in the snow beside the toboggan.

I didn’t think the woman had seen us. She was making a heroic effort to move up the hill in snow that deep, let alone pull a sled loaded with kids. Darla was fifty or sixty feet from them when the woman finally looked up.

She screamed—a wordless yell of surprise and fear.

Darla kept skiing toward her as slowly as the hill allowed.

“Stay away from me!” the woman yelled. She turned away from the crown of the road, pulling the toboggan toward the ditch. Somehow she managed a burst of speed. “They’re my babies! Mine! You can’t have them!”

The snow had drifted deep in the ditch. The woman fell into it, floundering in snow over her head. The toboggan tilted and came to rest at a steep angle, halfway in the ditch. The girl at the back of the toboggan toppled sideways.

I expected to hear crying, but it was eerily silent. The woman thrashed in the snow, trying to right herself. The two little kids stared as Darla and I approached, their eyes shining with fear. The older girl still hadn’t moved.

Darla got to where the woman had left the center of the road. She kept going, skiing past the woman and her children.

I looked at the toboggan. I couldn’t see the older girl’s face, only her pink snowsuit and a lock of her hair, brilliant yellow against the stark white snow.

I turned toward the ditch. My skis instantly caught in the fresh powder, and I fell in a ten-point face-plant. When I dug my way out of the snow, two women were screaming at me.

Darla: “What are you doing, Alex? Christ!”

The woman: “Get away. Get away, devil man!”

I ignored them both, of course. Nobody ever claimed I was smart. I reached down, unclipped my skis, and forced my way through the snow toward the girl in pink. I called out in the softest, calmest voice I could muster, “I won’t hurt you. I want to help.”

Darla had snowplowed to a stop twenty or thirty feet on down the hill and was sidestepping laboriously back toward me. The woman yanked on the rope, pulling her toboggan close. It slid smoothly out from under the girl, leaving her sprawled alone in the snow.

The girl’s face was porcelain white, her lips pale blue. I put my fingers against her mouth. She was breathing, but unconscious. Her ungloved hand felt hard and cold. The tips of her fingers were black.

The woman had been digging through her suitcase. I saw a flash, a glint of light on metal. She’d pulled out a meat cleaver. She waved it frantically, slashing the air above the two little kids’ heads. She was still yelling, variations on the theme of demon from Hell, leave my children alone.

“I won’t hurt her,” I said. “I want to help. She needs help.” I picked up the little snow-suited body in my arms. She weighed nothing. I looked around—there were scraggly looking stands of leafless trees on either side of the road. No evergreens or anything else that looked like easy shelter.

Darla huffed up to me, out of breath from sidestepping fast. “This is crazy, Alex. Warren. Your family. If we try to help everybody who’s suffering, we’ll never get close.”

“I don’t want to help everyone. I want to help this little girl.”

Darla looked away.

“Can we build a shelter in those trees? We need a place to warm her up and spend the night.”

Darla sighed. “I saw a car down the hill a ways. It might work.” She picked up my skis and poles, bundling them with her own poles. She turned and slid back down the hill.

I looked at the crazy woman. She was holding the cleaver above her head. Her other arm was wrapped protectively over the other two kids. She’d quit yelling, but now she was growling—a low, gravelly noise that would have made a pit bull cower.

I backed up a few steps and then turned to follow Darla. Trudging through the deep snow was hard work. Darla quickly got fifty or sixty feet ahead of me.

The girl’s right arm flopped away from her body. The dull black of her frostbitten fingertips looked unnatural against the backdrop of snow. I unzipped my coat and jammed her hand inside against my chest. Even through two layers of shirts, it felt icy.

Darla had stopped by a large rectangular hump in the snow. By the time I caught up, she’d dug a trench about two feet deep along one of the short sides of the hump.

“How can I help?” I said.

“Try to keep that girl warm. And keep an eye on Crazy Mommy over there.”

I looked back the way I’d come. The crazy lady hadn’t moved; she was still hovering over her other two kids in the ditch. I couldn’t see the cleaver.

I unzipped my coat completely. The little girl hadn’t moved or even made a sound, but tiny puffs of frosty air emerged from her lips. I hugged her to my chest and tried to zip up my coat around both of us; it wouldn’t fit, so I had to settle for holding it around her.

Darla was digging in the ash layer by then. She used the front of a ski, stabbing it into the ash and scraping it out of the hole. I remembered the ash as being mostly white, but against the snow it looked dirty gray.

A bit of the vehicle emerged as Darla continued her assault on the ash. First, a strip of maroon paint—part of the car’s roof, maybe. Then, as she dug deeper, she exposed a section of black-tinted auto glass. It was vertical, so I figured she was digging out the back end of a van or SUV.

It was going to take forever. She’d barely cleared a two-square-foot section of one back window. Getting the whole back end of the vehicle unburied might take hours, and even then, wouldn’t it be locked?

“Done,” Darla said. I looked questioningly at her. She smiled and said, “Here goes nothing.” She took a spear grip on one of the skis and rammed the butt end through the window. The glass shattered into a thousand tiny pebbles that rained into the interior of the vehicle. Darla scraped the ski along the edges of the hole, clearing away the remnants of the window. Then she slid through it, feet first. I heard her voice, muffled by the car, “It’s good. Pass the girl in.”

I crouched in the hole and handed the girl to her. “I’ll try to warm her up,” Darla said. “Get some wood. We need a fire.”

“Okay.” I passed our skis, poles, and packs through to her and then slogged toward the scraggly copse near the road.

Every tree was dead—their few remaining lower branches snapped off easily. That was a relief, since any fallen wood was buried under deep snow. But would anything grow again in the spring? Would there even be a spring?

I crawled through the broken window with an armload of firewood. Inside there was a shadowy space, maybe six feet square, between the window and the first bench seat. The ceiling was low; I couldn’t stand, only crouch. Darla and the girl lay against the back of the seat, wrapped in both our blankets. Darla’s backpack was beside her on the floor; Jack peeked out the top.

I built a small fire on the floor to one side of the entry hole. The fire gave off an acrid, chemical reek at first. I figured the fire was burning the carpet. Some of the plastic door trim melted, too. Most of the fumes rose through the hole in the window, so it wasn’t too hard to breathe, so long as I kept my head low.

The nasty smell got me thinking. “Isn’t it dangerous to build a fire inside a car? What if there’s gas in the tank?”

“This is a big SUV, an Expedition I think. The gas tank will be up here, under me. It’d have to heat up to four– or five-hundred degrees to explode without a spark. We’ll be okay.”

I kept the fire very small, despite her reassurance. Even so, the inside of the truck got toasty-warm in no time. I stripped off my coat and overshirt. Darla still lay with the girl, both wrapped in blankets. Sweat glistened on her forehead.

I was tending the fire a bit later when the woman’s face appeared outside the hole. Her eyes blinked from the smoke. The meat cleaver followed, held in front of her mouth like a shield. I scrambled back a couple feet. “Where’s my Katie?” the woman said. “You fixing to roast her? Give her back, you damned-to-Satan filthy cannibals.”

“Cannibals?” I didn’t know what else to say. The accusation, the mere idea of it, shocked me into silence. I held up both my hands, hoping to calm her.

“Give her back, so I can bury her proper.”

“Bury her?” Darla said. “She’s not dead. I’m trying to warm her up.”

“Poor baby was dead ten miles up the road. Fever and the runs got her. She was cold as a rock.”

“Well, this rock is doing an awfully good job breathing, lady.” Darla pulled the blanket down, exposing Katie’s head. She held the back of her hand to the little girl’s mouth.

“She was dead. I was trying to find a safe place to bury her.”

“We’re trying to warm her up,” I said. “She’s got hypothermia and frostbite. You can come in and check on her if you want. But you’ve got to leave that cleaver outside. We’re unarmed.” My empty hands were still up. The unarmed bit was a lie—I had the chef’s knife and hatchet on my hip, turned away from her. Plus, the gun from the guy who’d killed himself was in my backpack, but without bullets, that hardly counted as a weapon.

The woman’s eyes swiveled from me to Darla. She stared, and I realized it wasn’t Darla she was looking at but Katie, nestled in Darla’s arms. The cleaver disappeared and the woman slithered through the window headfirst. She fell with a thunk on the floor next to the fire. Darla unwrapped the blankets from herself and Katie and handed the girl to her mother. The woman clutched Katie to her chest and backed into the corner where the rear seat met the wall. Darla wrapped both of them in our blankets.

I heard a faint mewling noise outside and crawled to the smoke hole to stick my head out. The toboggan was about ten feet away. The youngest kid, really only a baby, was crying softly while the older one, who couldn’t have been more than four himself, tried to quiet her. “Shh. Mommy said shh,” he whispered over and over.

I looked at the woman. “Your kids are cold and scared. They can come in here with you, if you want.”

She stared at me for a long time. Finally she nodded.

“I’ll hand them in to you,” I told Darla. She shook her head no, but I figured she was expressing her general disgust at the whole project, rather than refusing to catch the kids.

I crawled out of the truck and pushed through the snow to the toboggan. “Your mom’s inside. It’s warm in there. Will you come with me?”

The older kid went dead silent and rigid as a board. The little one started screaming. So much for my way with kids. I hope I’m never a dad. I’d probably suck at it.

I picked up the bigger kid. He reeked of urine. He stayed stiff while I passed him through the window, which helped; I don’t know if we could have got him through the little hole if he’d been windmilling his arms.

The little one did fight and scream. I had to clamp her arms to her sides to shove her through the hole.

I dragged the toboggan closer to our shelter. On impulse, I opened the suitcase resting at the front of the toboggan. It held mostly clothing. There was no food, no way to start a fire, no water or water bottles, and no pans. At the bottom, I found three framed pictures. One showed the entire family: the woman, three kids, and a tall, kind of geeky-looking guy. The other two were wedding photos. The woman looked young and so happy, I got the impression that she might float away in her billowy white dress. The guy looked younger and even more geeky in his rented tux, but he had this smug smile, as if he were saying he’d found the best woman, and the rest of us would have to settle for leftovers. I gently repacked all three pictures amid the clothing. I added the woman’s cleaver to the top of the suitcase and zipped it shut.

Inside, all three kids were pressed against their mom. The back of the SUV was crowded with six people and a fire. I rummaged through our pack.

“What are you doing?” Darla whispered.

“Making some dinner.”

“Alex, we should move on. Find another camp for tonight. We’ve helped them enough.”

“I went through their suitcase.” I was whispering, but the woman no doubt could hear me in the tiny space. “They don’t have any food or water bottles. Who knows how long it’s been since they’ve eaten.”

“And who knows how long ’til we’ll eat again if you give away all our food.”

“I won’t give it all away.”

“Where are we going to get more when we run out?”

“I don’t know.”

I made corn pone for everyone. Darla insisted that we give our guests only one pancake each—any more and they might vomit, she said. Then I melted snow to refill all the water bottles and passed those around.

The woman had gone silent. She took the food and water without comment, but her suspicious eyes glared at me, and she kept her back firmly against the wall. Katie was still unconscious, but the other two kids gobbled up everything I offered them.

* * *

That night, I spread our blankets on the bench seat. When I asked Darla to join me, she refused. “I’m going to keep watch half the night,” she said. “I’ll wake you up when it’s my turn to sleep.” I wasn’t sure how she’d figure out when half the night had passed, but knowing Darla, she had a way to do it. I lay down alone and let sleep claim me.