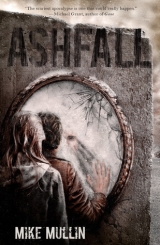

Текст книги "Ashfall"

Автор книги: Mike Mullin

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Chapter 45

I was awakened by someone kicking me accidentally as they tried to leave the tent. I grabbed my backpack and rolled out into the snow. Darla told me nobody had bothered the tent after I’d gone to bed—evidently the first shift was the busy one.

Breakfast was the same as the day before: a mad crush and two-hour wait for six ounces of boiled rice each. The guards sprayed yellow blobs of paint on our left hands, partly covering the blue from the day before.

We lay down in the tent after breakfast and took a nap together. Darla wedged the backpack between us.

I woke to Darla shaking me. “Hey, sleepyhead. I think it’s time for the Baptists’ food line.”

“Okay.” I shook myself fully awake and packed our blankets.

This time we lined up separately. Darla was an inch shorter than I, so she could stand about forty feet ahead of me. The same two yellow coats were out chatting with kids and organizing things.

Our new strategy didn’t help. There were still at least one hundred kids in front of Darla when the yellow coats ran out of food and the line dispersed.

We caught up with the same longhaired lady we’d talked to the day before.

“Thanks for the almonds yesterday,” I told her.

She glanced around. “You might be mistaken—perhaps someone else gave you almonds. We’re not allowed to share our personal rations. Most of us would like to, but it caused . . . problems.”

I whispered, “Well, thank your twin sister for me then, would you?”

She smiled and whispered back, “Okay, I will.”

“I was wondering, why don’t you get the wheat off that barge?”

Darla elbowed me in the side. “Don’t talk about that, we might need it later,” she hissed.

“There are a lot of people here that need it worse than we do,” I whispered back.

“Wait, what are you two talking about?” the woman said. “A barge?”

“Yeah, there’s a barge stuck in Lock 12, not far from here. It’s loaded with wheat. Must be hundreds of tons of it.”

“Lock 12?”

“On the Mississippi, in Bellevue. The barge is stuck in the lock. It might be tough to unload, but there’s plenty of manpower here.”

Darla let out an exaggerated sigh. “The wheat would have to be ground. But I know how to make a mill. Or we could improvise a zillion mortars and pestles. Like Alex said, there’s plenty of manpower here.”

“And it’s not far?”

“I don’t know, exactly. Fifteen or twenty miles, tops.”

“Sounds like the answer to one of my prayers. You can show us where it is?”

“Sure, no problem. But it’s right there in the lock, easy to find.”

“What are your names?”

“I’m Alex. Alex Halprin. This is Darla Edmunds.”

“Georgia Martin.” She held out her hand. I hesitated a moment since mine was filthy, but she clasped my hand in both of hers, then shook Darla’s, too. “Good to meet you both. Let me talk to the mission director. I’ll look for you here tomorrow and let you know if we need you to show us the barge.”

* * *

It didn’t take that long. The next morning, we’d been waiting in the breakfast mob for about an hour when the loudspeakers mounted on the fence posts crackled to life. “Alex Halloran and Darla Edmunds, report to Gate C immediately. Alex Halloran and Darla Edmunds, Gate C.”

“Guess that’s us,” I said.

“Guess so, Mr. Halloran.”

I scowled at Darla. “Well, it sounds sort of like Halprin.”

“Hope this doesn’t mean we’re going to miss breakfast.”

We fought our way out of the mob and jogged diagonally across the camp to the same gate we’d come through on our first day. As we approached, I saw Georgia standing on the other side of the fence with an older guy. His face was a little droopy, as if he’d lost a lot of weight recently, and he had a neatly trimmed fringe of hair around his otherwise bald pate. Georgia said something to the guards and they waved us through.

“Thanks for coming. This is Mission Director Evans—”

“Call me Jim, please,” the bald guy said. “Very exciting news you brought yesterday. How much wheat did you say is on the barge?”

“I only looked into one of them, but it was packed. And there were nine barges tied together and stuck in the lock. If they all carried the same thing, I don’t know. . .”

“Hundreds of tons,” Darla said.

“Mysterious ways. . .” Director Evans muttered. Then he added out loud, “We have an appointment to see Black Lake’s camp commander, Colonel Levitov. Shall we go?”

He led us into one of the large tents. It was a pavilion, really, much bigger than even the tent my cousin Sarah had had at her wedding reception two years before, but subdivided inside. We followed Director Evans through a maze of canvas corridors and rooms until we reached a small office. A guy in fatigues sat behind a metal desk, typing into a laptop.

“Morning, Sergeant,” Director Evans said. “We’ve got an appointment with the colonel.”

“He’s running late. Have a seat.”

That presented a problem. There were four of us and only two unoccupied chairs in the room. Darla and I stood to the side and looked at Director Evans and Georgia.

“Have a seat,” Director Evans said.

“We can stand,” I said.

“No, please. With how few calories you’re eating, you need to be off your feet far more than we do.”

I sank into a chair, and Darla took the one beside me. Evans was right. I was tired and hungry, or maybe tired because I was so hungry. I’d been hungry for three days now, but it was better not to think about it. Not that it was possible to not think about it. Just Evans’ comment about calories was enough to bring my empty stomach to the top of my mind. Maybe because it was morning, I thought about breakfast food. Donuts. Bagels. Wheaties, for some reason, even though I hated Wheaties. I put my head on my knees and tried to think about something, anything else.

We’d been waiting fifteen minutes or so when someone shouted from the other side of the canvas wall behind the sergeant’s desk: “Coffee!” The sergeant left the room for a few minutes and returned with a steaming ceramic mug. The smell rekindled my hunger so powerfully that I was almost nauseated. He carried the mug through a flap in the wall and then returned to his desk.

We waited another twenty or thirty minutes. I heard a shout, “Ready!”

“You can go in now,” the sergeant said.

We entered another small office and saw another metal desk, another guy in fatigues, and another laptop. He picked up his mug and knocked back the last of the coffee. I caught myself staring at the mug and had to force my eyes away from it. There were no chairs except the one the guy occupied. He stood and stretched his hand out, “Director Evans. Good to see you.”

“Thanks for seeing us, Colonel,” Evans said, shaking his hand vigorously.

The colonel looked at me and wrinkled his nose. He didn’t offer to shake. “The purpose of this meeting is?”

Evans gestured at me. “This young man found a large supply of wheat, maybe several hundred tons.”

“Where?”

“Lock 12, in Bellevue, Iowa,” Evans said. “On a barge stuck in the lock.”

“I know the place.”

“I’d like your support to retrieve it—we could set up teams of refugees to grind it to flour. It’s a chance to get the camp’s caloric intake up to something sustainable. Exactly what we’ve all been praying—”

“I’ll kick it up to Black Lake admin in Washington. Thank you for the intel. Dismissed.” The colonel sat down and turned his attention to his computer.

“What?” I said. “That’s it? Enough food for the whole camp and—”

“Sergeant!” the colonel yelled, without looking up from his computer.

Evans wrapped his arm around my shoulder, and I allowed him to hustle me out of the office back to the camp’s main enclosure.

Of course we’d missed breakfast.

Chapter 46

We saw Georgia again at the yellow coat food line that afternoon. She apologized at length for making us miss breakfast and even smuggled another handful of almonds into my pocket. We ate them fast and furtively, huddled against the fence.

We spent the balance of that afternoon outside the vehicle depot, watching a guy work on a bulldozer. It was parked about thirty feet away on the far side of the fence.

We’d been watching him awhile when Darla yelled, “Hydraulic control valve’s messed up?”

The guy looked up, wiped his oily hands on his trousers, and stared at Darla for a couple seconds. “Yeah, how’d you know?”

“Just guessed. You disconnected the fluid reservoir and the control linkage, that thing between them just about has to be the control valve, right?”

“Yeah. It’s shot.”

“Ash gets in there and tears them up, I bet.”

“It’s worse on the dozers, ’cause they stir up the ash and come back covered in it. They’ve all gone bad—the garage tent is packed full of dozers with wrecked control valves.”

“That’s rough.”

“This one’s had it. I’m out of valves. Distributor we get ’em from is out, too. Major’s going to have my ass. He’s all hot to clear Highway 35 north of Dickeyville.”

“I bet you could make a master cylinder out of a truck work. As a control valve, I mean.”

“No way. The fittings wouldn’t be the same size, for one thing.”

“My dad and I built a hydraulic tree digger a few years ago. Used old master cylinders off junk pickup trucks as controllers. I dunno where he got the lifters, but they weren’t that much different from the ones on that dozer.”

“And that worked?”

“Worked great. We moved a bunch of trees from Small’s Creek to the farmyard. Then we sold the rig. Dad said he got two grand for it.”

“Not bad.” The guy messed with the dozer awhile longer, draining hydraulic fluid into a bucket and wiping parts off with a rag. “What’d you say your name was?”

“Darla Edmunds.”

“Nice to meet you. I’m Chet. See you around, maybe.” He picked up his toolbox and the bucket of oil and walked away.

* * *

Guard duty was crazy that night. I’d only walked two circuits of the tent when I caught the first invader, a little boy trying to worm his way into the tent—probably only looking for a warm place to sleep. I’d already dragged him out by his ankles when I realized how small and skinny he was. I thought about waking the tent boss—surely we could find a corner to accommodate this waif, but before I’d made up my mind, the kid ran away.

That’s the way it went all night—the moment I caught someone trying to sneak into the tent, they’d leave. Some of them backed away from me slowly, some sauntered off, but most ran. Nobody wanted a fight, thank goodness. Even the group of four adults I caught loitering by our tent flap about an hour after dark moved on without a peep of protest.

At first, I thought maybe they were giving up because of me. Maybe news had spread, and I’d acquired a reputation for my mad “kung fu” skills. I flattered myself with that idea for a minute before realizing it was total bull. First, something like fifty thousand people were penned in the camp. There was no way even a small fraction of them could have heard about the incident yesterday. Second, it hadn’t been an impressive fight. I’d twisted a guy’s arm, so what? Third, it was so dark that nobody would recognize me anyway, even if I did have a scary rep.

While I was thinking about it, I ran an old guy off. He was trying to sneak into the tent sideways, so I grabbed him by the shoulders and pulled him out. He weighed next to nothing. He must have been rail thin, although I couldn’t tell from looking at him, since he had at least two blankets tied around himself with scraps of old rope. Pulling him upright brought his face within a few inches of mine. A dirty beard clung beneath his gaunt cheeks. I let go of him, and he almost fell over before regaining his balance and stumbling off into the night.

These people weren’t afraid of me; they were starving. All of us were starving. I felt weak, and this was only my third day with so little to eat. The folks who’d been here since the eruption must have been near collapse. That also explained why so many of the would-be intruders were kids—they’d been getting more food than everyone else. Kids and newcomers were the only ones with enough energy to try raiding the tents.

It didn’t seem likely that Darla and I would be getting any food from the Baptists except an occasional handful of almonds. We were too tall and too old—unless something changed, they’d always run out of food before we made it to the front of the line. Already we were weakening. We had to get more food—and soon.

Chapter 47

The next three days were infuriating. Every morning we fought our way to the front of the breakfast line to get paper cups of rice. After breakfast, we’d wander over to the vehicle depot. Twice we saw the mechanic, Chet. Once he came over to the fence and talked to Darla for a while, speaking in some foreign language that might best be named “Diesel Truckish” (or should it be “Diesel Truckian”? Whatever). Every afternoon we stood in the Baptists’ food line, but they always ran out before we got to the front. We saw Georgia every day, and every day she had the same news for us: nothing. Colonel Levitov hadn’t told Director Evans anything about the wheat, and the Baptists couldn’t go get it without trucks and support from Black Lake. Keep praying, Georgia said.

Prayer is all well and good, but I wanted to do something. Darla looked thinner every day, and she’d been slender to start with. I felt as if we were being hollowed out from the inside, so our skin might soon collapse, leaving only a papery husk to mark our passing. I figured my backpack could hold enough wheat to keep us both alive for a month or more. If something didn’t change soon, I planned to try climbing the fence, razor wire and guards notwithstanding.

The next day, our sixth in the camp, something did change. Not long after breakfast, the camp’s loudspeakers came on with a hiss. At first I ignored them, but when I heard Darla’s name I tuned in. “Edmunds report to Gate C immediately. Darla Edmunds, Gate C.” I glanced at her and saw her shrug.

When we got there, the gate was closed. Chet was on the far side, chatting with the two guards.

“Did you call me?” Darla asked Chet.

“Yeah, that idea about using brake master cylinders as control valves on the dozers? You want to try it?”

“Try it?”

“Sure, I had road ops tow in four pickups yesterday. We can scavenge the cylinders off them. I’ve got all the tools we need and a full shop . . . so, you in?”

Darla was quiet a moment. Thinking, I figured. I said, “You should—”

“What’s it pay?” Darla asked.

“Pay?” Chet said.

“Yeah, you want me to help fix your dozers; I ought to get paid, right?”

“I guess so, but getting a job at Black Lake is really hard. I’d have to go to the colonel, and I dunno if—”

“I don’t need money. I want three square meals a day. For me and for Alex. And I’ll fix as many dozers as you want me to.”

“Um . . . I can feed you when you’re working. Maybe two meals. But if I let you take food back into the camp, I could get fired. Couple a guys caused a riot that way two weeks ago, giving food to girls through the gate. And I only got authorization for one assistant.”

Darla was quiet a moment. “No. If we can’t both eat—”

“Do it!” I whispered. “We’ve got a lot better chance if one of us gets enough to eat.”

“You sure? It doesn’t seem—”

“I have to get back to work,” Chet said.

“Okay. Two meals. One before work and one after, every day. And I start after the camp breakfast.”

“Come on, then.” Chet opened the gate.

Darla gave me a peck on the lips and trotted through the gate after Chet. I watched as they walked across the administration compound and through another gate into the vehicle depot. I kept watching until they disappeared inside a huge canvas tent that served as a garage.

It was strange, being alone. There wasn’t much to do; Darla and I had already visited the latrine trench, refilled our water bottles, and gone through the breakfast line that morning. I’d spent almost every minute with Darla for the last five weeks; being separated was . . . uncomfortable. It felt a bit like being naked in a room full of clothed people. Not that I’d ever done that, but I imagined it’d feel like I did right then.

I found a spot out of the wind where I could crouch beside a tent and still see the vehicle depot. I spent the rest of the morning and the early afternoon there, watching. When it was time to line up for the yellow coats’ dinner, Darla still hadn’t emerged from the garage. I was getting a little worried, but there was nothing I could do, so I crossed the camp diagonally to try my luck with the food line.

My luck held: bad, same as always. The food line dispersed even quicker than usual. There were three hundred, maybe four hundred kids between me and the last one who had gotten anything to eat. The only kids short enough to get fed looked to be eight or nine. Obviously nobody had gotten any wheat off the barge yet. The Baptists’ food supply was getting smaller, not bigger.

Georgia wasn’t there, either. There were two yellow coats organizing the line, but one of them was new. I caught him as everyone was leaving and asked about Georgia.

“Don’t know if I’m supposed to say anything about that.”

“Come on. She’s a friend.” When I said it, I was only trying to get information, but then I realized it was true.

The guy shrugged. “Where’s the harm? She went home.”

“She didn’t tell me she was leaving.”

“It was a sudden thing. Some kind of dispute with Director Evans.”

“About what?”

“That’s all I’m going to say. I’ve got to go help clean up.”

I trudged to the vehicle depot. There was no sign of Darla there, so I walked to Gate C, where she’d met Chet that morning. She was standing a few feet outside the gate, waiting for me. There were grease stains on her shirtsleeves and a big splotch of oil on her jeans. I didn’t care. I wrapped her up in a tight hug.

“Let’s go to the tent,” she said.

“Okay.” I took her hand and we started walking. “How was it?”

“Not bad. Chet’s not much of a mechanic. He didn’t even know to open the bleeder valve when you’re draining brake fluid. He didn’t get the line clear, so when I pulled the first master cylinder, I got oil all over myself.”

“I wouldn’t have known any of that stuff, either.”

“You’re not getting paid to be a mechanic.”

Nightfall was at least two hours off, but there were two people in our tent when we got there. They seemed to be asleep—resting, I guessed. We ignored them and shuffled to the back, where we knelt side by side, facing the corner. Darla reached down the front of her jeans. She didn’t need to unbutton them to accomplish this, which reminded me how much weight she’d lost—weight she couldn’t afford to drop. She pulled out a crumpled plastic package and surreptitiously passed it to me.

I glanced at the front of the package. Something was written there, but it was too dark in the tent to read it. I ripped off the top of the package. An intoxicating scent wafted to my nose: chocolate. Saliva filled my mouth, and I felt a little dizzy. I hoped the other two people in the tent were sick; maybe stuffed-up noses would keep them from smelling that heavenly aroma. I ate a piece—the first chocolate I’d had in seven weeks. Somehow it tasted even better than I had remembered.

The bar had been crushed to crumbs in Darla’s pants. I poured myself a handful of chocolate and threw it into my mouth. I ate like a starving beast, but then again, I was starving. I wasn’t a beast, though. I stopped myself before I’d wolfed it all and offered some to Darla. She put her lips against my ear and whispered, “No. Eat it all. I had one already. I’d have smuggled them both to you, but Chet was watching me too closely. Sorry.”

I snarfed the rest of the chocolate and licked the inside of the package. Then I licked off my hands, which gave the chocolate a gritty, sulfurous taste. I stuffed the wrapper into my pocket. I’d find a place to bury it later.

Chapter 48

The next morning, Darla insisted that I eat her cup of rice as well as my own. I tried to argue, but she was right. She’d gotten two full meals out of Chet yesterday—MREs, the prepackaged meals the military gives troops in the field. She was probably eating ten times as many calories as I was.

Four more days passed like that. I’d heard nothing about the wheat. The yellow coats didn’t know anything about it. When I asked to see Director Evans, they told me he was busy. Clearly the yellow coats were running out of food; the line broke up faster and faster each afternoon. Darla kept forcing her ration of rice on me, but despite the extra food, it got harder to stay awake and march circles around the tent each night on guard duty.

Darla, on the other hand, got more energetic and cheerful. Two solid meals per day were doing wonders for her. I took the first guard shift as usual, but twice she woke and relieved me before I’d finished my 360 circuits of our tent.

Darla got in the habit of sleeping in her “clean” set of clothes and changing into the greasy ones right before she went to work. That way only one change of clothes got messier. Although, to be frank, the grease was probably cleaner than the dirt that covered us head to toe. There was nowhere to wash clothes in the camp, nowhere to bathe or take a shower. Everyone was filthy. My head itched terribly. I hoped I didn’t have lice, but I was afraid to ask Darla to check.

I watched the vehicle depot while Darla was at work. Usually, I couldn’t see anything. They did most of their work in the big tent they used as a garage, which made sense because it kept them out of the wind. Sometimes I’d see Chet moving a dozer or towing a pickup truck into the garage. Once I saw Darla driving a bulldozer. Chet was crammed into the seat beside her. I couldn’t hear what they were saying, but she laughed about something. The blade on the front of the dozer lifted and dropped. It looked like Chet was teaching her to drive it. I should have been grateful to him for giving Darla a job and making sure she got enough to eat, but right then I wanted nothing more than to smack him silly.

Since I wasn’t getting any answers from the yellow coats about the wheat barge, I pestered the guards. Every time I saw a new one on gate duty, I asked about it. None of them knew what I was talking about.

Finally, I thought to ask Chet. He picked up Darla at the gate every morning and brought her back at night, since she wasn’t allowed to be outside the refugee enclosure unescorted. He hadn’t heard of the wheat barge, either, but at least he listened. I told him the whole story: how we’d met with Director Evans and Colonel Levitov and told them about the bounty of wheat on the Mississippi. And how we’d heard zilch about it ever since.

“I don’t know anything about it,” Chet said. “But if you don’t have anything else to do, you guys can wait here, and I’ll go see what I can find out.”

“Sure,” I said. Of course we didn’t have anything else to do. Duh.

We waited about twenty minutes. Then Chet emerged from one of the admin tents with Captain Jameson in tow—the guy we’d met the first day, the one who’d ordered Jack shot. I hoped he wouldn’t recognize us. Maybe he did, because as he passed through the gate to where we stood, his lips thinned and hardened, forming a cruel sneer. “The maintenance man tells me you two know something about a wheat barge. How’d you learn about it?”

“We’re the ones who found it,” I said. “We told Colonel Levitov about it.”

“Oh? I guess we owe you, then. But it’s classified now. Don’t talk about it anymore.”

“Classified? What? Why—”

“We won’t tell anyone,” Darla said. “I’ve got a good job helping Chet. You can count on us.”

“Good.” Captain Jameson turned to go.

“But where’s the food? Why are we eating rice when there’s all that wheat nearby?” I said.

“Wheat’s not ours. The colonel kicked it up to Washington. Turns out Cargill owns it.”

“Cargill?” I asked.

“Huge grain distributor,” Darla replied.

“Yeah,” Captain Jameson said, “Black Lake got a nice contract to guard it until they can pick it up. Bonuses all around, I hear.”

“People are starving!” I gestured with my clenched fists, which was better than what I really wanted to do with my fists.

“People are starving all over. There’ve been food riots in fifty-six countries.”

“Countries?” I said. “What, did some other volcanoes erupt?”

Captain Jameson gave me a condescending smile. “Nope, the U.S. produced twenty percent of the world’s grain. And even before the volcano, there was less than a two-month supply. All that’s gone. Whole world’s starving, except the people with the guns. We’ve got more security contracts than we can service, but I guess you wouldn’t know anything about that, would you?”

“All I know is that people are starving right here, right now, and there’s plenty of food close by.”

“What, you think we should steal that food? That’s private property, son. Plus, I’d get fired. Maybe we do owe you for bringing it to our attention—I’ll see that Chet gets you a candy bar or something.”

I didn’t know what to say. I stood and stared at him in total disbelief.

He cast his eyes at Darla. “Look, if you’re that desperate, your girl could get some extra food entertaining soldiers in the evenings. Lots of girls are doing it, some not as pretty as she is.”

Something about the way he said “your girl”—as if I were her pimp, not her boyfriend—stoked my fury past the boiling point. I screeched like the wail of a roiling teakettle and lashed out, kicking Captain Jameson squarely in his nose. His head snapped back, and his nose erupted with blood. He fell backward into the snow. I stepped forward, intending to beat on him a bit more, but the gate guards closed on me from either side. I blocked the one on my left, but the guy on my right clubbed my temple with the butt of his gun. I went down. As he raised his gun again, Darla screamed, “Stop! Don’t—” Then the gunstock dropped and the world went dark.