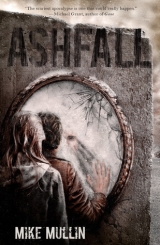

Текст книги "Ashfall"

Автор книги: Mike Mullin

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Darla quit chewing. “Gross.” She thought a moment and then swallowed. “No. If a cow eats grass, and we eat the cow, then we aren’t grass eaters. In fact, we can’t eat grass. Cows have a special digestive system for that.”

“Yeah, I guess you’re right.” I thought about it for another second or so, then served myself another slab of side pork.

It took all afternoon and part of the evening to finish roasting the meat. We spitted all the different cuts over the fire, which worked okay. Some of the meat was a bit burnt, and some was tough and hard to eat, but it would keep us alive.

We buried the meat in a snow bank to freeze it. Darla worried about wild animals getting into it. I didn’t think that would be an issue because all the wild animals had probably died of silicosis. But it couldn’t hurt to be careful, so I spread the plastic tarp over our cache and weighed it down with three logs.

After a late dinner, I built a fire in the farmhouse’s living-room hearth. I poked around in one of the bedrooms and found two clean flannel shirts. We discarded the overshirts we’d been wearing, as they were both drenched in pig blood.

There were two bedrooms in the house, both with queen beds. They looked pretty inviting to me: plenty of room to spread out and, uh, do whatever. Darla said it was too cold in the bedrooms. She was right. We did just fine on the ratty old couch in front of the fire.

Chapter 41

Not long after we left the pig farm the next morning, we came back to Highway 52. I groaned. We’d spent two days skiing in a circle, damn it. At least we’d found the pigs—even though it had been disgusting, I felt a lot better with a full stomach and a heavy pack stuffed with pork on my back.

We weren’t at the same place where we’d crossed 52 before. There was no sign of St. Donatus or the two sentinel churches. “You think we’re north or south of where we hit 52 the first time?” I asked.

“South, probably. We were heading east, and we mostly turned right.”

“Those roads were pretty twisty, though.”

“Either way, if we turn right, we’ll eventually hit Dubuque. I’m not sure where 52 goes if we turn left, but I think it follows the Mississippi River.”

I thought about Katie’s mom and her failed attempt to cross the Mississippi. “I don’t want to go to Dubuque.”

“Me, either. Left it is.”

The highway ran along a ridgetop for a few miles and then veered left and began a long decline. We picked up speed as the slope grew steeper—I raced along behind Darla, trying to stay in her ski tracks. The wind felt icy on my face, but still it was fun; soon we were laughing and screaming as we shot down the hill.

We flew past a green road sign: Welcome to Bellevue, Population 2337. Then the road flattened out, and we were coasting through a quaint riverside town. Or rather, the buildings were quaint with lots of dark-brown brick and an old-fashioned main street. The town itself was weirdly deserted. There were no tracks in the snow, no signs of people. We skied past Hammond’s Drive In, Horizon Lanes, and a Subway. The storefronts gaped like monstrous maws, shards of glass in their smashed windows forming transparent teeth.

Darla and I had fallen into an uncomfortable silence, mirroring the eerie quiet of the town. To break it, I asked, “Where are all the people?”

“I dunno. Crossed the river to get help from FEMA, maybe?”

I saw a drugstore, Bellevue Pharmacy. Its windows were smashed, too. “Let’s go in there and look around.”

“You think they have some food? We’ve got plenty of pork, but I wouldn’t mind some variety.”

“Well, um . . .” I felt the blood rush to my face and looked down.

“Condoms.” Darla shook her head, but to my relief, she was smiling. “Okay. Look for sanitary supplies, too. I’d kill for something better than rags.”

The drugstore had been thoroughly picked over. We searched for over an hour, even pushing two fallen shelving units upright to look underneath. We found nothing. Well, not exactly nothing. If we’d wanted to know what the latest celebrity gossip had been in August, there were plenty of magazines in the rack to inform us. The small electronics aisle was pretty much untouched. Hair dryers, curling irons, electric shavers, and electric toothbrushes were there for the taking. But everything useful—food, condoms, sanitary supplies, and drugs—was long gone.

“That blows,” I said as we gave up the search.

Darla squeezed my hand. “We’ll figure something out.”

We skied down a hill to the river. The Mississippi itself had changed. A few years ago, my family had taken a three-hour riverboat cruise in Dubuque. Back then, the river had been wide and powerful, filling its banks from tree line to tree line. Now it was a narrow silver thread winding through a gray plain of ashy sludge. Upriver, I could see two barges, both partially grounded in the ash.

The area at the bottom of the hill was fenced-off. A sign on the chain link read: Mississippi Lock and Dam Number 12.

“Maybe we can cross here,” Darla said.

“How? If the lock’s closed, sure, but—”

“Let’s check it out.”

That made sense—it couldn’t hurt to take a look. I climbed the fence. Darla tossed our skis over and followed me. The dam started at the far bank of the river and extended about three-quarters of the way across. Between us and the dam there was a lock, a huge channel over a one hundred feet wide and six hundred feet long, defined by massive steel and concrete walls at each side and a set of metal gates at either end. The upstream gate had been left wide open. The downstream gate was open, too, forced ajar by a barge stuck within its jaws. Atop both the gates and the walls ran wide metal catwalks. Dead fish lolled belly up in the water below us. It smelled atrocious, like the time Dad had brought home a bunch of bass from a fishing trip, gutted them, then left the trash in the garage for three weeks. (Actually, I was supposed to take the trash out. Whatever.)

“How are we going to cross that?” I said.

“We’ve got rope. We’ll climb down onto that barge.”

“The drop looks like twenty-five or thirty feet. How will we get up the other side of the lock?” From where I stood, it looked like a long drop onto the barge’s hard, metal deck.

“I’ll improvise something.”

We climbed over another chain-link fence. That put us on the open-gridded metal walkway alongside the lock. We stepped along the catwalk, lugging our skis, and made a forty-five-degree turn as we followed it over the top of the lock gate. The ash and snow had fallen through the grid of the catwalk, but it was still slick with ice. I felt uneasy; there was nothing but a low, metal fence between me and a very long drop to the water below.

When we reached the end of the gate, directly above the stuck barge, Darla dug the rope out of my backpack. She bundled the skis and lowered them to the barge’s deck, where they landed with a clang. Then she looped the other end of the rope around the top bar of the railing and lowered herself down hand over hand, clutching both strands of rope.

Darla yelled “Come on down!” just like a game show host.

I wasn’t too sure. It looked like a long way down. And I wasn’t very comfortable with heights. When I was in fourth grade, Dad had taken me to a huge sporting-goods store that had a climbing wall. He had needed new ski goggles, or something like that. Anyway, I bugged him ’til he let me try the climbing wall. It was easy and fun—I scampered up in no time. But when I stood at the top and peered over the edge, ready to turn around and rappel down, I just . . . couldn’t. Couldn’t turn around. Couldn’t step backward over the edge. Couldn’t even pull my eyes away from the drop. One of the store’s employees had to climb up and pretty much drag me off the edge so another guy could lower my rigid body. I spun on the way down, slamming my ankles into the wall, but I couldn’t move—I was frozen in terror. As far as I knew, Dad never told Mom or Rebecca about that incident. But he’d never offered to take me back to that sporting goods store, either.

I climbed slowly over the railing and got a good grip, holding the ropes with both hands. I didn’t want to step off the metal platform. A little voice in my head screamed at me: Don’t do it! You’re going to fall! You’re going to die!

But I couldn’t let Darla show me up. And this was the best way across the river. Plus, I wasn’t in fourth grade anymore. I’d faced far more dangerous situations over the last six weeks: the looters at Joe and Darren’s house, Target, the plunge into the icy stream. I could do this. I would do this.

Darla yelled, “Any day now.”

I scrunched my eyes closed and stepped off, slowly lowering myself hand over hand.

I let out a sigh when my feet touched the deck. Darla said, “You’re afraid of heights, aren’t you?”

“Uh, not really.”

“It’s okay.”

“Just a little, I guess.”

“You did good, Alex.” She kissed me. If she’d asked me to join a Mt. Everest climbing expedition at that moment, I might have agreed.

Darla pulled on one end of the rope so it snaked free of the railing above us. On the far side of the barge, the other half of the lock gate loomed above us. “Hand me the hatchet, would you?”

Puzzled, I pulled it off my belt and passed it to her.

She tied the free end of the rope around the handle. “Watch out.” She backed up a couple steps and threw the hatchet, aiming for the rail above our heads. The hatchet glanced off and fell back onto the deck with a clang. Darla tossed it again. This time the hatchet went over the top rail, but when she pulled on the rope it came free and clanged back down to the barge. “This may take a while.”

I wandered away, both to avoid the tumbling hatchet and to check out the barge. It was really nine barges connected by chains with a tugboat at the back. I saw a large hatch in a nearby deck and tried it—it was heavy, but I could lift it.

I expected to find coal or iron ore, something like that. Instead, it was full to the brim with golden-brown grain. I scooped up a handful and let the hatch crash shut. I wasn’t sure what it was, but it looked edible—and there was a lot of it.

Darla yelled, “Hey, I got it!”

I hurried back to her, clutching the grain in my hand. She’d thrown the hatchet up over the railing so that its head had caught on the middle rail and the rope looped up over the top rail. It didn’t look very safe to me: if the knot came loose, or the hatchet broke, or the haft disconnected from the head, or it slipped off the rail, then the rope would come loose, pulling the hatchet down with it.

“What’s this?” I asked, holding out the handful of grain.

“Wheat. You get it out of that hatch?”

“Yeah. This barge is packed full of it.”

“Nice—if we had a way to grind it, we could make bread. Or tortillas, at least.”

“You think Jack would eat it?”

“I dunno, wouldn’t hurt to try. I’m pretty much out of cornmeal to feed him.”

We walked back to the hatch, and Darla held it open while I scooped out kernels of wheat. My backpack was full of pork, but I fit in some wheat by dumping it over the top and letting it fill the cracks around our other supplies. I dumped some wheat into Darla’s pack, too, right alongside Jack, but he didn’t seem interested in it.

“Maybe we should stay here for a while,” Darla said.

“I want to find my family. Besides, there will be food at my uncle’s farm. They have ducks and goats and stuff.”

“There’s literally tons of food here, enough to last until it spoils—a few years, at least. Plus, it’s hard to get down here—probably nobody will bug us. We could shack up in the tugboat’s wheelhouse, build a grinder for the wheat, and we’re golden.”

My chest felt suddenly heavy. I didn’t want to choose between my family and Darla. “I need to find my family. Maybe we can come back here and get more wheat after we find them. And I bet there will be other people after this grain soon enough. Surely there’re a lot of hungry people out there who need it worse than we do.”

Darla shrugged. “I guess so.” We walked back to the precarious-looking rope Darla had rigged.

“You’re going to climb that?” I asked.

“Yeah. If the rope comes free, catch me and dodge the hatchet, okay?”

“Um, right.”

“Kidding.” Darla climbed the rope slowly and steadily. She used only her arms, pulling herself up hand over hand to disturb the setup as little as possible. Damn, but she was strong. Maybe it was all the farm work. I couldn’t have climbed the rope like that without using my legs.

When she reached the top, Darla untied the hatchet and fastened the rope to the railing. I tied the skis onto the other end of the rope, and Darla hauled them up. Then we repeated the process with my backpack. When we finished that, I grabbed the rope and started laboriously climbing.

“Want me to pull you up?”

“No, no—I got it.” No way was I going to ask for help after watching her slink up the rope so easily. I made it, too, even though I had to wrap my legs around the rope to climb. I was glad I hadn’t needed to go first—all my thrashing probably would have caused the hatchet to come loose.

Now we stood on a narrow metal walkway atop the other half of the lock gate. We followed the walkway until it dead-ended against the dam. There was yet another catwalk atop the dam about twenty feet above us. An ordinary metal door was set into the wall of the dam. I tried the knob; it was locked.

“I think I can use the hatchet trick again to climb to the top of the dam,” Darla said.

“I’ve got another idea.” I took the hatchet and reversed it, so I could use it as a hammer. I whaled on the doorknob, raising the hatchet high above my head in a two-handed grip and bringing it down hard. It took ten or eleven blows, but then there was a ping and the knob finally broke. It bounced on the metal walkway and fell into the river, leaving a round hole in the door where the knob had been. I stuck my finger in the hole and pulled. Nothing—the door was still locked.

“Let me try something.” Darla took the knife off my belt, knelt in front of the door, and jammed the blade into the hole. She dragged the knife to her left. There was a click, and the door swung smoothly open toward us. “You broke the lock, but there’s a slide in there you have to operate.” She never stopped amazing me.

A metal staircase inside led upward to another door—fortunately unlocked, at least from the inside. It opened onto the top of the dam. From there, crossing the Mississippi required only a short hike along the last catwalk.

We had to climb an eight-foot, chain-link fence to get off the dam. When I looked back toward the lock, I saw a sign on the fence: Hazardous, Keep Out! U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. On this side of the fence, there was an earthen dike with a narrow, snow-covered road running atop it.

We put on our skis and followed the road roughly east for a couple of miles until we’d left the river completely behind. Nobody had been here for at least five days—no tracks marred the snow.

We came to another fence. The gate across the road was chained and padlocked, but it was easy to climb. The sign on the far side read: Keep Out! Hazard! Superfund Site, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. That seemed a little confusing—was it an army site or an EPA site? At least everyone agreed it was hazardous, although we’d come through it fine.

The road continued past the gate and over a railway embankment. At the far side of the embankment, the road teed into a highway. We stopped and stared: the highway had been plowed.

Chapter 42

Before the eruption, a plowed road would have been no big deal. But this was the first clear road I’d seen since I left Cedar Falls, the first real sign of civilization. And it wasn’t only the snow; the ash also had been scraped up. We could see honest-to-God blacktop here and there. Tall berms of snow and ash flanked the highway.

“Which way?” Darla asked.

“Left, I guess. Warren should be northeast of here. It’s near the Illinois/Wisconsin state line, east of Galena.”

The road presented a problem. We couldn’t ski on the blacktop, so we tried the side of the road, but between the huge piles of plowed snow and ash and the underbrush beyond, there was no good place to ski. Finally, we unclipped our skis and carried them, walking north on the road.

We’d been walking a little more than an hour when we heard an unfamiliar noise: a faint whine coming from around the bend in the road. It took us a minute to figure out what it was . . . a car or truck, racing along the highway toward us.

“Let’s get off the road,” I said. Darla nodded, and we stumbled across a pile of ash and snow almost as tall as I was. Even if we’d wanted to, there was no good place to hide. The brush beside the road was leafless, and we’d left all kinds of tracks crossing the snow berm.

A truck roared into view ahead of us. It was a six-wheeled army dually with a cloth cover over its load bed, like a modern version of the Conestoga wagon.

The driver slowed as he approached the spot where we’d left the road. I saw printing in huge letters on the side of the truck: F.E.M.A. Below that, in smaller print, it read: Black Lake LLC, Division of HB Industries.

“Finally, some help.” I thrashed back across the snow berm, waving my arms to attract the driver’s attention. The truck stopped a little bit past us. Two guys in camo fatigues rode in the back. One of them was huge, the other almost as small as me. They both had black guns dangling from straps around their necks: Uzis, maybe.

The small guy jumped down. The big one stood on the back fender and trained his gun on us.

I swallowed hard and glanced at the gun above me. It looked like a toy in the guy’s massive hands. “Um, hi,” I said. “We’re trying to get to Warren. I’ve—”

“Where are you from?” the little guy said.

“Cedar Falls.”

“Serious? Damn, we don’t get many from that far into the red zone.”

“Any way I could get a ride to Warren? I’ve got family—”

“Hop in, we’ll take you to the camp.”

“Okay,” I said. The big guy stepped aside and let his gun hang loose from its strap. Darla and I tossed our skis and poles into the truck bed and climbed in after them.

There were two people huddled inside already, a woman and a young boy. They looked dirty and tired, travel-worn. I said hi, but neither of them responded. Darla and I sat on a bench about halfway between them and the guards.

The truck had been roaring along for fifteen or twenty minutes when Darla whispered, “We’re going the wrong way. The truck’s going south.”

“What? They said they were taking us to the camp.”

“Well, we’re going south. And we need to get to Warren, not some camp, anyway.”

“I figured we could walk to my uncle’s place from the camp—if it’s the one we heard about near Galena, it’s close.”

“Maybe. But we’re getting farther away right now,” Darla whispered.

“Where are we going?” I yelled in the direction of the small guard.

He looked my way but didn’t say anything.

“We’re trying to get to Warren—it’s near Galena.”

He shrugged. “We’re on a sweep. We’ll loop around to the camp and drop you there. It’s outside Galena.”

“O-kaaay,” I said doubtfully, but he had already looked away.

The truck stopped six or seven more times. Each time, one of the guards hopped out and one stayed in the truck with us. We never saw the driver, although we heard him over the guards’ radios. Twice, they picked up more passengers: a guy by himself, then a family of four.

It was late afternoon by the time we finally arrived at the camp. The truck stopped for a bit, then rolled forward. We heard a clang and, out the back of the truck, caught a glimpse of a big chain-link gate. It looked to be at least twelve feet high, not counting the coils of razor wire at the top. I shivered: Was that fence designed to keep us in or someone else out?

The guys from the truck herded us into a huge white tent. Two new guards took charge of us there. They looked nearly identical to the others: young guys in camo fatigues with submachine guns. I tried to talk to them, to find out what was going on or whether we could get a ride to Warren. The only answer they’d give me was to wait and ask the captain. Every few minutes, the guards led a group of refugees through a flap in the tent—to the processing area, they said. There was nothing to sit on, and the plastic floor was filthy with mud, so we stood beside one of the canvas walls.

Eventually, a guard told us to follow him. He led us down a short, canvas-walled hallway to a large room—either the tent was subdivided into rooms, or we were in a new tent. There was a small metal desk in the center of the room. A gray-haired guy sat at it, typing on a laptop. Otherwise, the desk was bare. Two more guys in fatigues stood behind him, slouching as if bored. Freestanding shelves hid most of one of the walls and held a wide assortment of stuff: a dozen knives, two handguns, a shotgun, two rifles, some canned food, and a bunch of unidentifiable bundles and bags.

“Welcome to Camp Galena,” the guy behind the desk said in a monotone. When I got close, I could read his nametag: Jameson. “Under the terms of the Federal Emergency Relief and Restoration of Order Act, you are subject to military rules of incarceration and must obey all orders given by camp personnel. In addition, you must read and follow all rules posted at the camp mess. Failure to—”

“Excuse me,” I said, “we’re trying to get to Warren. It’s not far.”

“You’re from Iowa, right?”

“Yeah, Cedar Falls.”

“Refugees from red zone states are specifically forbidden from travel in the yellow or green zones for the duration of the emergency.”

I shook my head, feeling stunned. Forbidden to travel? I’d just traveled over one hundred miles on skis. I bit back an even snarkier comment and said instead, “If you’ll drop me off in Warren, I won’t be a refugee.”

“Do you have any contraband to declare?”

“No—and what about a ride to Warren?”

“You evidently have confused Camp Galena for a taxi stand.”

What an asshole. I swallowed that thought and said, “I’m happy to walk.”

“As I’ve already told you, it’s illegal for you to travel within the state of Illinois. This will go a lot smoother if you restrict yourself to answering my questions, son. Remove your backpacks.”

The two guards looked much more alert now. They’d taken a couple steps toward us. I glanced at them and took a half step back, dropping into a sparring stance. I kept my hands at my sides, though. “Could you get word to my uncle in Warren? I’m sure he’d pick us up.”

“Your name will be published in the camp roster. If your uncle exists and can show proof of relation and means of support, you’ll be released to him.”

“What about Darla?”

“Son, we’ve got forty-seven thousand inmates here. I do not have the time or the patience for this. Remove your backpacks. That will be the last time I ask.”

“You didn’t ask the first—”

“I’m not from Iowa,” Darla said. “I’m from Chicago. I was in Cedar Falls, visiting family. Alex and I met on the road.”

I looked at Darla, puzzled. She scowled back. I took the hint and kept my mouth shut.

“I’ll need to see proof of residence. Driver’s license, utility bill, or similar.”

“My, um, a house we were staying in on the way here caught fire. My I.D. burned.”

“I do not have time for this. Corporal, remove their backpacks.”

“Captain.” One of the guards moved behind me, grabbing my pack. The other one stood to one side of us, fingering his gun. I was tense and furious, but fighting would have been pointless. There were three of them in the room, armed and ready, and I had no idea how many more guards might be within earshot. I shrugged out of my pack.

The guard behind me set the pack aside and yanked the knife and hatchet off my belt. He put them on the shelves with the other knives. Then he patted me down from behind, feeling under my arms, my sides, the insides of my thighs, and down to my ankles. He repeated the process on Darla. Then he picked up one of our skis. “What do you want me to do with these, sir?”

“Put them on a shelf.”

So our skis, poles, and my makeshift staff went on one of the empty shelves. Next he opened the top of my backpack. It was stuffed with packages of meat wrapped in newspaper. The corporal picked one up and sniffed it. “Pork,” he said. The meat all went on the shelves, too. Then he got a plastic bin off a shelf and poured the loose wheat kernels into it. He found the bulletless revolver in a side pocket and placed it with the other handguns.

The only things left in my backpack when he was done were the frying pan, a blanket, and some clothing. “That’s our food. And my dad’s skis. I need that stuff—how are we supposed to survive without even a knife?”

“Weapons and personal caches of food are prohibited at Camp Galena,” Captain Jameson said.

“I don’t even want to be here. Why don’t you give me back my stuff, and I’ll go?”

The captain ignored me. In the meantime, the corporal had opened Darla’s pack. He pulled out Jack. “Got a live one.”

“Deal with it,” the captain ordered.

The corporal stepped through a flap in the wall of the tent, carrying Jack.

“Wait!” Darla yelled. “What are you doing?”

I heard the crack of a gunshot. Darla ran toward the flap, and the other guard grabbed for her, but missed. I followed Darla.

Outside the tent, the snow had been trodden into a packed, icy mess. There was blood in the snow, some fresh, some old and frozen. The corporal holstered his pistol. Darla bent over a large wooden bin.

I looked into the bin. Jack lay there, twitching and bleeding from the huge, ragged hole a bullet had punched in his head. Beside him lay a golden retriever and a German shepherd, their frozen limbs tangled together. They’d been shot in the head, also.

“What did you do that for?” Darla screamed.

“Orders. No pets allowed.”

“Murderers!” Darla ran at him, her fists flailing wildly. I took a half step forward, ready to unload a number-two round kick on the guard’s face. But out of the corner of my eye I saw three more guards rushing toward us. Plus, the whole area was fenced—there was no way to escape. Fighting was useless, so I checked my kick.

The corporal hit the side of Darla’s face with a vicious backhand, knocking her down. He bent over her, cocking his fist for another strike. I dove on top of Darla. The guy hit my back, but since I’d blocked his punch short of its intended target, it didn’t have much force.

Darla struggled under me. I tried to hold her still and keep her head and body protected. Someone caught my right hand and wrenched my arm behind my back. I felt a plastic loop around my wrist, cutting into it as he cinched it tight. Then my left wrist was forced to join the right and locked into the other half of the handcuffs.

Someone grabbed me under my arm and dragged me off Darla, setting me upright. They cuffed her as well and marched us back into the tent.

The captain still sat at his desk. Darla strained against the guy holding her and yelled, “What the—”

“Quiet!” Captain Jameson roared. “I’ll overlook this behavior since you’re new here, but one more word and you’ll start your stay at Camp Galena in a punishment hut.”

I watched Darla. She screwed up her face to start yelling at the guy again. I kicked her ankle. She glowered at me, her face twisted into a ferocious scowl. I shook my head.

It worked, because Darla didn’t say anything else, and we didn’t learn what a punishment hut was. At least not right at that moment. The guards marched us to a gate in the fence and cut off the handcuffs. Then they thrust our backpacks into our arms and shoved us through the gate.