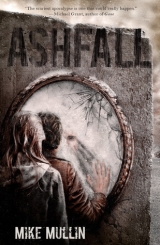

Текст книги "Ashfall"

Автор книги: Mike Mullin

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Chapter 3

The sound hit me physically, like an unexpected gust of wind trying to throw me off my feet. Two windows in the house next door bowed inward under the pressure and shattered. Darren stumbled from the force, and I caught him with my left hand.

I used to watch lightning storms with my sister. We’d see the lightning and start counting: one Mississippi, two Mississippi . . . If we got to five, the lightning was a mile away. Ten, two miles. This noise was like when we’d see the lightning, count one—and wham, the thunder would roll over us-the kind of thunder that would make my sister run inside screaming.

But unlike thunder, this didn’t stop. It went on and on, machine-gun style, as if Zeus had loaded his bolts into an M60 with an inexhaustible ammo crate. But there was no lightning, only thunder. I glanced around. The firefighters were running for their truck and the knot of rubberneckers had scattered. The sky was clear. I could barely make out a couple of columns of smoke in the distance, but those had been there for more than an hour. Nothing obvious was wrong except for the godawful noise.

My hands were clamped over my ears. I had no memory of putting them there. The ground thumped against the soles of my sneakers. Darren grabbed my elbow, and we ran for his front door.

Inside, the noise was only slightly less horrendous. The oak floor in Darren’s entryway trembled under my feet. A fine waterfall of white plaster dust rained from a crack in the ceiling. Joe ran up carrying two stereo headsets and a roll of toilet paper. A third headset was clamped over his ears. He pantomimed tearing off bits of toilet paper and stuffing them in his ears. Quick thinking, that. Joe was definitely the brains of the couple.

I jammed a wad of toilet paper into each ear and slapped a headset on. The thunderous noise faded to an almost tolerable roar. But I heard a new sound: my ears ringing, like that annoying high-pitched whine a defibrillator makes when a patient is flatlining on TV.

We probably looked silly, standing there with the black cords dangling from the headsets, but nobody was laughing. I shouted at Joe, “Should we go to the basement?” But I couldn’t even hear myself talking over the noise.

Joe’s lips moved, but I had no idea what he was saying. Darren was shouting something, too, but the noise of the explosions drowned out all of us. Joe grabbed me and Darren and towed us toward the back of the house. We ran through their master bedroom—it was the fanciest bedroom I’d ever seen, but with the auditory assault we were enduring, I wasn’t about to stop and gawk.

The master bathroom was equally impressive, at least what I could see of it by the dim light filtering in from the bedroom. Pink marble floor, huge Jacuzzi tub, walk-in shower, bidet—the works. But best of all, it was an interior room, placed right in the center of the first floor. So it was quiet, sort of. When Joe closed the door, the noise diminished appreciably. Of course, that plunged us into total darkness. Joe reopened the door long enough to dig a D-cell Maglite from under one of the sinks.

I held my hands out at my sides and screamed, “Now what?” but I don’t think they could hear me. I couldn’t hear myself.

Joe yelled something and pointed the flashlight at the tub. Darren and I didn’t respond, so after a moment Joe stepped into the tub, knelt, and covered the back of his neck with his hands.

That made sense. The tub itself was plastic, but it was set into a heavy marble platform. If the house fell, it might protect us. Maybe we’d be better off outside, in the open, but the explosive noise was barely tolerable even now, in an interior room. Joe stood up, and I stepped into the tub beside him.

Joe shined the flashlight on Darren’s face. It was red and he was shouting—I saw his mouth working, but his eyes were wide and unfocused. His arms windmilled in wild gestures. Joe stepped out of the tub and hugged him, almost getting clocked by one of his fists in the process. Darren tried to pull away, but Joe held tighter, stroking Darren’s back with one hand, trying to calm him.

The beam from the flashlight lurched around the room as Joe moved, giving the whole scene a surreal, herky-jerky quality. He coaxed Darren into the tub, and all three of us knelt. It was a big Jacuzzi, maybe twice the size of the shower/tub combo I was used to, but we were still packed tightly in there. I put my head down on my knees and laced my fingers over the back of my neck. Someone’s elbow was digging into my side.

Then, we waited. Waited for the noise to end. Waited for the house to fall on our heads. Waited for something, anything, to change.

My thoughts roiled. What was causing the horrendous noise? Would Joe’s house collapse like mine had? For that matter, what had hit my house? I couldn’t answer any of the questions, but that didn’t keep me from returning to them over and over again, like poking a sore tooth with my tongue.

I wasn’t a religious guy. Mom was into that stuff, but I had won that fight two years ago. Except for Christmas and Easter, I hadn’t been inside St. John’s Lutheran since my confirmation. Before then, I had gone pretty much every Sunday, sometimes voluntarily.

When I was eleven or twelve, we had this real old guy as a Sunday school teacher. Mom said he’d been in some war: Iraq, Vietnam . . . I forget. Anyway, almost every class he’d say, “There are no atheists in foxholes, kids.” At the time, it was just weird. What did we know about either atheists or foxholes? Nothing. But I sort of understood it now.

So I prayed. Nobody could hear me over the noise—I couldn’t even hear myself—but I guess it didn’t matter. It was probably better that Joe and Darren couldn’t hear me, because it didn’t come out too well. “Dear God, please keep my little sister safe. I don’t know what these explosions are, but don’t let them hurt my family. They’re probably in Warren, but I guess you know for sure. I swear I’ll do whatever the hell you want. Go to St. John’s every Sunday, try to be nice to my mother, whatever. Do what you want to me. Just please keep Rebecca, Mom, and Dad—” Thinking about my family got me crying. I hoped prayer counted without the amen and all at the end. I was pretty sure it did.

I don’t know how long I knelt at the bottom of that tub. Long enough for my tears to dry and my neck to cramp.

I stretched out, kicking someone. Joe lifted the flashlight, and by its light we rearranged ourselves so we were lying in the tub instead of kneeling. We were still packed in there way too tightly. Someone’s knee dug into my thigh. I tried to rearrange myself but just got an elbow in my shoulder instead.

Then we waited some more. Two hours? Three? I had no way of knowing. The noise didn’t abate at all. What could make a noise that loud for that long? Thinking about it made me feel small and very, very scared. The smell of fear filled my nostrils—a rancid combination of smoke and stale sweat. The flashlight started to dim, and Joe shut it off—to save the batteries, I figured.

Sometime later, someone kicked me in the chest. Then I felt a shoe on top of my hand and jerked it away quickly to avoid getting stepped on. Joe snapped on the flashlight. Darren was standing up, feeling for the edge of the tub. He stepped out gingerly. Joe shrugged and followed him.

I got out of the tub, too. The sweaty plaster dust from my house had dried on my arms and face, making me itch. I twisted the handle on one of the sinks. The water came on, which surprised me. Nothing else was working; why should that have been any different? I washed my arms and face as best I could in the darkness. I realized I was thirsty again and gulped water from my cupped hands.

While I was cleaning up, Joe had left the room. Darren was sitting on the edge of the tub, staring at his hands folded in his lap. Now Joe returned, carrying an armload of pillows, blankets, and comforters. He spread a comforter in the bottom of the Jacuzzi, added a pillow and a folded blanket, and gestured with the Maglite for me to get back in. I pulled off my filthy sneakers.

I climbed into the Jacuzzi and lay down, fully dressed. I felt bad about dirtying their comforter with my nasty clothes, but who knew what might happen later. If something else bizarre went down and I had to run, I sure didn’t want to do it butt naked. I lay on my left side in the Jacuzzi, one pillow under my head, the other clamped on top over the headphones and the toilet paper. The headphones dug into my temples, but that was a minor annoyance. I could still hear both the explosions outside and the ringing in my ears.

It’s hard to fall asleep when Zeus is machine-gunning thunder at you. It’s hard to stay awake after an evening spent surviving a house fire. It took a couple more hours, but eventually sleep won, and I drifted off despite the ungodly noise and vibration. Everything would be better tomorrow. I thought: a new day, a new dawn would have to be better than this.

I was wrong. There was no dawn the next day.

Chapter 4

I woke up and groaned. Everything hurt. My back ached from lying curled in the tub. My right shoulder had frozen up overnight. The muscles in my legs and bruises on my knees screamed with pain. My head throbbed, and my mouth tasted of ash and fungus. I rolled onto my back, throwing the pillow off the top of my head.

Losing the pillow was like turning up the volume on the radio four notches—if the radio happened to be playing a thrash band with five drummers. That damn noise. It was still every bit as loud as it had been the night before. I checked the toilet paper in my ears, making sure it was still securely jammed in. The headset had dislodged when I rolled over, so I put it back on, which helped a little.

I had no idea what time it was, but I felt like I’d slept for six, maybe eight hours. So the explosions, thunder, or whatever they were had gone on at least that long? What could make a noise like that? Everything I could think of—bombs, thunder, sonic booms—would have ended hours ago. It was warm in the bathroom, but my hands and feet still felt cold and numb. I stayed in the bottom of the tub for a while, trembling and trying to get my breathing under control.

But lying around in the bottom of a Jacuzzi wasn’t going to answer any of my questions. I pushed myself out of the tub and fumbled in the darkness for my shoes. Putting on shoes one-handed in darkness so complete that I couldn’t see the laces or my hands was a bit of a trick. I gave up on tying them—my right arm wouldn’t cooperate with the left. I jammed the laces down into the shoes so I wouldn’t trip.

I needed to take a leak. But Darren and Joe had sacked out between me and the toilet last night. I had no idea if they were still there, and I really didn’t want to kick them in the dark. After all, I was a houseguest. Sort of a weird houseguest—a fire refugee, sleeping in their bathtub—but still. I figured I could hold it for a while.

I had a general memory of where the door was—a few steps diagonally from the head of the bathtub. I stretched out my left arm and shuffled in that direction. Of course I found it by jamming my middle finger painfully against the knob. I slipped into the master bedroom and closed the door behind me.

Blackness. It was so dark I couldn’t see my hand held in front of my face. I’d expected the bathroom to be dark since it was an interior room. But last night I’d been able to see fine in the bedroom—the three huge windows let in plenty of light. Even if it was still nighttime, I should have been able to see something. The darkest overcast night I’d ever been in hadn’t been this black.

I’d been in darkness like this only once before. About five years ago, Dad took me and my sister into a cave on some land one of his friends owned. Mom flatly refused to go. I didn’t like the narrow entrance or the tight crawlways that followed, but I endured it without complaining; I couldn’t let my sister show me up, after all. I even got through the belly crawl okay, pulling myself along by my fingers, trying not to think about the tons of rock pressed against my back.

We stopped in a small but pleasant room at the back of the cave to eat lunch. After we finished, Dad suggested we turn out all our lights to see what total darkness was like. I couldn’t see anything, not even my fingers in front of my eyeballs. As we sat there, it got more and more claustrophobic, like a cold, black blanket wrapped around my face, smothering me.

I grabbed for my flashlight, only to feel it slip from my sweating hands and clatter to the cave floor. I groped for it but couldn’t find it. Next thing I knew, I was screaming in my high-pitched, ten-year-old voice, “Turn it on! Turn on the light! Turn it on!”

Now, the darkness was exactly like the cold black blanket that had smothered me at the back of the cave. I stifled a sudden urge to yell, “Turn it on!” The only flashlight was back in the bathroom with Joe and Darren. And Dad was over a hundred miles away.

I stumbled forward, found the bed by banging my shin into the metal bed frame, and sat down. Putting a dirty butt-print on the bed probably wasn’t the nicest thing to do, but it couldn’t be helped. The world had tilted under me—I had to sit down or fall down, and I had enough bruises already.

The gears in my brain ground over the possibilities, trying yet again to make sense of what was happening. Nuclear strike? Asteroids? The mother of all storms? Nothing could account for everything that had happened: the thunderous noise, the flaming hole punched in the roof of my house, the dead phones, this uncanny darkness.

A beam of light shining from the bathroom cut through the room. Darren appeared in the doorway; I could see his face in the backwash from the flashlight. The light poked around the bedroom a bit and came to rest on me.

Darren said something. I couldn’t hear him over the noise, but I could sort of see his lips. Maybe, “Are you okay?”

I shrugged in response. Then I stood up and pantomimed taking the flashlight and going to the bathroom. Darren nodded and handed it over. As I walked into the bathroom, Joe passed me on his way out.

I used the toilet and washed my hands at the closer of the two sinks. The water still worked, but the pressure seemed to have dropped since yesterday.

Back in the master bedroom, I handed the flashlight to Darren and mouthed “Thanks” at him. He and Joe walked to a window on the other side of the room and pointed the flashlight at the glass.

The beam died not far outside, snuffed out by a thick rain of light gray dust falling slowly, in a dense sheet that blacked out all light. Little drifts of dust clung to the muntins dividing the window panes. I tapped the glass, and a bunch of the stuff sloughed off and drifted down, joining the main flow raining down unceasingly.

Darren took two steps backward and collapsed onto the bed. The flashlight in his hand trembled as he sat there, staring at his feet. Joe sat beside him and put an arm around his shoulder. I could see Darren’s shoulders shaking—the cord dangling from his headphones wavered—so I turned away to give them some privacy.

I stared out the window, trying to figure out what the falling stuff was. It was light gray, like ash from an old fire, but a lot finer—sort of like that powder for athlete’s foot. I leaned closer to the window, trying to get a better look. What I got instead was a smell—the stench of rotten eggs.

Someone tapped my shoulder. I turned, and Joe gestured for me to follow. The three of us trooped out of the room using the flashlight to find our way. When we got to the entryway, Darren shined the flashlight on the front door. It was closed and presumably locked, but a two-inch drift of ash had blown under it. I reached down and touched the stuff—nothing happened, so I picked some up between two fingers. It was fine and powdery but also gritty and sharp, like powdered sugar but with the texture of sand. Slicker than sand, though. It reeked with the same sulfur smell I’d noticed at the window.

Joe was wearing a wristwatch. I held out my own wrist and tapped it. He nodded and pushed a button on the side of the watch, lighting the display. It read 9:47.

Joe led us into the kitchen and passed out Pop-Tarts for breakfast. We had no way to toast them, of course, but I was so hungry it didn’t matter. He pulled a half-full gallon of milk from the dark fridge. The milk was still cool, even after a night without power. We drank most of it.

The flashlight dimmed further while we were eating breakfast. Joe used it to retrieve a candle and matches from a kitchen drawer along with a pad of scratch paper and a pen. He carried everything back to the table. While Joe lit the candle and shut off the flashlight, I snatched the pen and scribbled, “What’s happening?”

Joe read my note and added his own below it. “Volcano. The big one. Yesterday, while you guys were watching the fire, I heard about it on the radio.” Joe passed the tablet around. I had to hold the note near the candle and hunch over to read it.

Darren took the tablet and wrote, “So that stuff outside is ash? From the volcano?”

I wrote, “Volcano? In Iowa?”

“No. The supervolcano at Yellowstone,” Joe wrote back.

“But that’s what—one thousand miles from here?” Darren wrote.

Joe took the tablet back and wrote for a long time. Darren tried to pull it away once, but Joe swatted his hand. “About nine hundred. The volcano had already gone off yesterday when Alex’s house was burning. You remember the big earthquake in Wyoming a few weeks ago? The radio said that was either a precursor or trigger for the eruption. The little tremor we felt yesterday was the start of the explosion. I don’t know what hit Alex’s house. My guess is that it was a chunk of rock blasted off the eruption at supersonic speed. Then about an hour and a half later, the sound of the explosion finally got here. The ash would be carried our way on the jet stream and take eight or nine hours to arrive.”

“Should we go check on the neighbors?” Darren wrote.

“Radio said to stay indoors during the ashfall. If you have to go out, you’re supposed to cover your mouth and nose.”

“What about my family?” I scrawled.

“They’re in Warren with your uncle, right?” Joe wrote.

“Supposed to be. How’d you know?”

“Your mother told us you’d be home alone this weekend,” Joe wrote. “She asked us to keep an eye out for you.”

Typical Mom. Of course she’d figure out a way to spy on me—although now I was happy she had. “Warren is 140 miles east of here, even farther from Yellowstone. It could be better there, right?”

“Yes,” Joe wrote. “There will be less noise and ash the farther you are from the volcano. There could be a heavy ashfall here but almost none in Warren.”

I hoped Joe was right. I hoped my family was in Warren. They should have made it—they’d left three hours before everything had started. I didn’t remember them talking about stopping for dinner on the way, but I couldn’t really know.

“How long is this noise going to last?” Darren jotted.

“The news didn’t even warn it was on the way, let alone say how long it would last.”

“What about the darkness?”

“Anything from a few days to a couple weeks. They didn’t know exactly how big the eruption was.”

We traded notes for another hour or so, rehashing the same information. Joe had already told us pretty much everything he knew. We’d burned more than half the candle and completely filled the scratch pad by then. Joe wrote, “I’m going to blow out the candle, to save it. Relight it if you need anything.”

The next few hours were, well, how to describe it? Ask someone to lock you in a box with no light, nobody to talk to, and then have them beat on it with a tree limb to make a hideous booming sound. Do that for hours, and if you’re still not bat-shit crazy, you’ll know how we felt. Before that day, I had no idea that it was possible to be insane with both terror and boredom at the same time. I’m not normally a touchy-feely kind of guy, but the three of us held hands most of that time.

Lunch was a huge relief, if only because it gave us something different to do. Joe squeezed my hand once and let go. I saw a couple little flashes of light, him using the light of his watch to find stuff. A few minutes later he was back, pressing food into my hand: a few slices of salami, a hunk of Swiss cheese, and two slices of bread. We finished off the milk as well, passing it around and drinking straight from the jug. Glasses would have been too much of a pain without light to pour by.

After lunch, more terrified boredom. Nothing to do but endlessly ponder: Is my family alive? Would I survive? I sat and thought for uncounted hours. Then something changed.

There was silence.