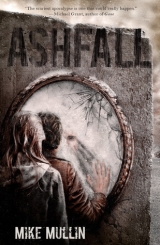

Текст книги "Ashfall"

Автор книги: Mike Mullin

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Chapter 38

Katie died during the night.

It happened after Darla shook me awake and took my place on the makeshift bed. Katie was alive then, but hot to the touch. Too hot, as if a fire were spreading under her skin. She lay in her mother’s arms, both of them mercifully asleep.

I watched her breathe by the firelight. She’d gasp and suck in a dozen breaths quickly, panting almost. Then she’d stop breathing for so long I’d wonder if she’d died—a minute, maybe longer. I laid my fingers gently on her neck the first few times she quit breathing—her pulse was fast and erratic.

I wished—no, wanted, needed—to do something for her. But I couldn’t even get her to take a sip of water. If we’d had any medicine, I didn’t know how we could have gotten her to take it without a syringe. But all that—medicine, doctors, and syringes—belonged to the pre-eruption world, the world that had died almost six weeks before.

A few hours later, Katie trembled for a moment. Her eyes snapped open and glanced left, then right. They were a rich blue, like the last August sky before the volcano. She drew a breath—a long, shuddering gasp—and then lay still.

I thought about doing something. Pulling her out of her mother’s arms and trying CPR, maybe. I knew how. I had taken a class Mrs. Parker had organized at the dojang. Maybe I should have tried to revive her. But it felt wrong. Instead, I found her hand, still hot with fever, and held it. Her blackened fingertips felt stiff and lifeless against my palm. After five minutes or so with no breathing and no pulse, I knew she was dead.

Everyone else—her mother, her brother, her sister, and Darla—slept through it. But I watched Katie die.

* * *

Hours later, after sunrise, her mom woke. She pulled her arm tighter around Katie and glanced down. Katie’s eyes were still open, staring at nothing and everything.

“She’s dead, isn’t she?” the woman asked.

I tried to reply. Something was stuck in my throat. No words would exit. Instead, I cried.

I felt a hand grip mine. I looked up. The woman was staring into my eyes.

“The troubles of this world can’t hurt my Katie now.”

“I wish I could have done . . . I’m sorry.”

The woman nodded. A moment later, a change came over her face, and her stare took on a suspicious cast. “You won’t eat her, will you?”

“Katie? God, no . . . who would do something like that?”

“There’s them that will. My Roger, he . . .” She fell silent for a long time. I held her hand and waited. “We ran out of food a week ago. Couldn’t get more. Katie was already sick. We decided to walk across the bridge in Dubuque: Roger, the kids, and me. Heard there’s a camp on the other side, near Galena. FEMA camp with food and medicine.”

“What happened?” I asked softly.

“Oh, we’d been told there were gangs in Dubuque, a couple of them, fighting over food and turf. Roger figured we could slip past them on side streets, get across the bridge. It didn’t work. Three guys found us. Roger fought them, and that gave me time to run off with the kids.”

She was quiet again for a while. Catching her breath or deciding whether to tell me the rest of her story, maybe. “I snuck back later, to see if I could help Roger. There was a whole group of them, at least a dozen. Right in the middle of Jones Street. They’d built a bonfire . . . . Above it, spitted like a pig, there was my Roger.” Her face was contorted with fury; she spat her words out. “They were roasting my Roger. Roasting him like a pig.”

I heard a groan from the front of the SUV.

“Darla? You okay?” I asked.

“Yeah. No.” Her head poked up above the bench seat. “What a story to wake up to. Christ.”

“I don’t think we’d better go through Dubuque. Maybe we can find another bridge or build a raft.”

“Okay. We’ll figure something out.”

“Every night since then I’ve had the same dream—nightmare, I mean. I see those men crowded around that fire. But they’re not cooking my Roger. Instead, it’s Katie over that fire. And she’s screaming. She’s screaming—” The woman broke down into quiet, choked little sobs. She let my hand go and clutched her daughter’s corpse to her chest. The other two kids slept through it all.

Darla volunteered to cook breakfast, so I went outside to try to dig a grave. I found a likely looking flat spot on the far side of the ditch. I cleared away the snow, mostly using my hands and arms. The ash layer underneath was frozen, but it was only a thin crust of ice. I broke it up with my staff and then scraped the ash up out of the hole using the butt end of a ski. Under the ash, the ground was rock hard. Little white tendrils of dead grass lay in clumps atop the frozen earth, bleached remainders of a dead world. I poked the ground with my ski. It was hopeless. Without a sharp spade or pickax, I couldn’t dig any deeper.

After breakfast, we carried Katie’s body out to the shallow grave. Darla suggested we take off her pink jumpsuit, in case one of the other kids needed it. The woman glared at her, and Darla shrugged. I mounded the ash up over the body, but it was a very shallow grave—twelve inches deep at best.

“I’m sorry I couldn’t dig any deeper. The ground is frozen solid.”

“It’s okay,” the woman said, “the ashfall claimed my Katie’s life, now it can have her body, too.”

I said a prayer over the grave. I’d been getting way too much practice at leading impromptu funerals. I hoped this would be the last one.

When we got back to the SUV, I saw Darla had repacked our gear. Jack was poking his nose out of the top of her knapsack. I opened my pack. We had five bags of cornmeal left. I pulled out three of them.

“What are you doing?” Darla’s eyes narrowed.

“I’m leaving them some food. They’ve got nothing to eat.”

“What the hell? And exactly what are we going to eat? That’s probably not enough to make it to Warren, even before you give most of it away.”

I didn’t answer. I didn’t know the answer. She was right. There wasn’t enough there for two of us to make it to Warren. I thought about Mrs. Barslow, who’d fed me steak and stayed up late to wash my clothes. She should have let Elroy run me off. Darla’s mom should have rolled me back out into the ash outside their barn. If all we did was what we should to survive, how were we any better than Target? I took out three water bottles and the frying pan.

“You can’t, absolutely cannot leave the pan here, Alex.”

“How are they going to melt snow for water? They don’t have one.”

“I don’t know, and it’s not my problem. Why didn’t they bring their own damn pot and water bottles?”

The woman had dropped through the hole into the SUV as we argued. “Roger had them in his pack: the water bottles and pans.”

“Christ.” Darla grabbed the knife, hatchet, and my staff and threw herself out of the SUV. “Just wait here!” she yelled back through the broken window.

“She’s right, you know,” the woman said. “You don’t owe us anything. You should keep your supplies. Keep your wife alive.”

“She’s not my wife.” Somehow, that made the situation feel even worse, the fact that she agreed with Darla. I took another bag of cornmeal out of the pack and set it with the pile of supplies I was leaving behind.

Darla was gone quite awhile. After forty minutes or so, we heard banging and screeching sounds coming from the front of the SUV. She returned a bit later, carrying a concave chunk of the truck’s front quarter-panel. Two edges were roughly sawn, as if Darla had used the hatchet or knife to cut the sheet metal. I’d had no idea that was even possible.

“You can melt snow with this. But watch the sharp edges around the kids.” Darla tossed down the improvised pan and jammed our skillet back into my pack.

“Thank you,” the woman said. “And . . . I’m sorry.”

Darla grabbed the woman’s coat and got right in her face. “We might die because of all the stuff my stupid, softhearted boyfriend is leaving you. So don’t you die, too. You take this stuff, and you keep yourself and your kids alive. You hear?”

“I hear.”

I didn’t care much for being called stupid and softhearted. The boyfriend bit I could live with.

Darla grabbed her pack and dove through the hole, going back outside. I grabbed the woman’s hand, gave it a goodbye squeeze, and followed Darla.

Chapter 39

Despite our late start, the day was still dim and overcast, adding to the now-normal haze of high-atmosphere dust and sulfur dioxide hiding the sun.

Darla set off at a furious pace. She stomped up the hill in a duck walk so fast I could barely keep up. We headed south on 151, following the tracks we’d made the day before.

About two miles on, we hit a crossroads. We turned left and set off across virgin snow.

Lunch was a sullen affair. We stopped and sat on a snow-covered guardrail. I dug out a strip of dry rabbit—our last meat, unless we ate Jack—and two cornmeal pancakes left over from breakfast. Darla got out a handful of cornmeal and fed Jack. Somehow, I didn’t think we’d be eating him any time soon. As we ate, I tried several times to start a conversation and got nothing but grunts in return.

The land had changed around us. The hills were steeper here and more wooded. Instead of the gunshot-straight roads we’d followed earlier in the journey, this road meandered, following hillsides, creeks, or ridgetops. There were fewer farms, too. We spent large parts of the day with nothing but a partly evergreen forest on either side of the road. Then, occasionally, we’d pop out into huge open areas surrounding a farmstead. All the houses appeared to be occupied, so we avoided them.

Late that afternoon, when I started looking for shelter, we were skiing through one of the wooded areas. I carefully watched the forest on either side for almost an hour, looking for a large pine broken near its base.

I found a tree that might work and yelled for Darla to stop. It was one of the biggest pines I’d seen here, with a trunk almost two feet in diameter. It had broken six or seven feet off the ground. Behind the stump there was a huge hump that looked like a snowdrift extending for sixty or seventy feet. I figured that had been the rest of the tree, now submerged in ash and snow.

Using my hands, I dug a small tunnel alongside the stump. The fallen tree had created a protected space underneath it. I took the hatchet from my belt and chopped off some of the downward-pointing limbs. That created a nearly ideal spot to spend the night: dry, warm, and hard to see from the outside. The pine branches would make for a soft bed, too.

I yelled out, “Come on in. It’s nice in here.”

Darla crawled through the hole and glanced around in the meager light. “Great idea. It even smells good.”

“Yeah, I spent one night under a tree like this a few days after I left Cedar Falls. It was okay. It might be a bit cold, but we’d probably better not light a fire in here. Too many dead pine needles.”

“It’ll be warm enough with two of us.”

We built a small fire in the snow outside and cooked corn pone. We used all of our cornmeal except for a few handfuls Darla saved for Jack. We wound up with enough pancakes for two more meals, maybe three if we rationed them.

After dinner, I made a bed in our shelter by laying out the tarp and both blankets. We snuggled together under the blankets. I’d taken off my coat, overshirt, and boots, but otherwise we were sleeping fully clothed—it was warmer that way. I probably smelled pretty foul, but Darla didn’t seem to mind. I could smell her sweat, too, but somehow it made me want to pull her closer, not push her away.

We lay there a long time. I couldn’t sleep, and I could tell from her breathing that she wasn’t sleeping either.

“I’m sorry,” I said, “about giving away most of our food, I mean.”

Darla rolled over. I couldn’t see her, but I felt her lips press against mine. We kissed—a long, wet smooch. “It was dumb.”

“I wouldn’t have survived if nobody had helped me. Mrs. Barslow, your mom . . . Anyway, you could have stopped me. It was your food, not mine.”

“It was our food. And I said it was dumb, not wrong.” She kissed me again. “I know I’ve been bitchy today—”

“No, you’ve—”

“I’m scared.”

I didn’t know what to say, so I didn’t say anything.

“It’s just . . . when I was on the farm, I knew we’d be okay. I knew where to get food. I knew where I’d sleep at night. Mom was . . . well, I knew I could get help. Now who knows where we’ll get anything to eat. Who knows what crazy crap we’ll run into tomorrow.”

“I won’t let anything happen to you, Darla. I promise.” Even as I said it, I knew it was stupid. All kinds of bad stuff could happen that would be totally out of my control. Still, it felt right.

We kissed again. I planted little kisses on the corner of her mouth, her cheek, along the line of her neck. When I kissed her ear, she giggled and pulled away. “That tickles.”

“The first time I saw you, I thought you were a funny-looking angel. They’re not supposed to wear overalls or ride bicycles, you know.”

Darla kissed me again. When we broke the kiss, she whispered, “I love you.”

“I love you, too.” The words tumbled from my lips without thought. I realized I was only giving voice to what I’d felt for a long while: I’d been in love from almost the moment we’d met.

“Do you think we’ll live through this?”

“We will.”

“How do you know?”

I shrugged. There was no way she could have seen the gesture, but we were pressed so tightly together, I was sure she felt it. “I believe we will.”

“I believe it, too.”

We fumbled with each other’s shirts. I felt the slick fabric of her bra pressed against my chest. Her fingertips traced the scar at my side, bumping over the ridges her stitches had left in my flesh. When her hand grabbed the tongue of my belt, I stopped her.

“What?” she asked.

“It’s um . . . I don’t think we should—”

“You’re not ready? Isn’t that the girl’s line?”

“Um, no, I want to—I want you. But what if you get pregnant?”

Darla let my belt slide out of her hand. “I dunno—I can’t worry about stuff that might happen nine months from now. I’m not totally convinced we’ll survive the next week.”

“We will.” I tried to sound confident, but I wasn’t totally convinced, either.

She wrapped her arms around me, and we held each other in the quiet darkness for a while.

“So, have you ever done it?” she asked.

I was glad for the darkness then; it hid my blush. “No. I only had one real girlfriend. Selene Carter. We, uh, messed around some, kind of like you and I are now.”

“That’s a pretty name, Selene. Is she still in Cedar Rapids?”

“I don’t know. I guess so. We broke up last spring.”

“She didn’t want to?”

“I dunno if I was ready. She wasn’t, or didn’t like me enough, or something. It wasn’t a big deal, really. I didn’t mind. Well, until she dumped me. I minded that.”

“I would . . . I mean, I feel like I’m ready, with you, anyway. But you’re right; it would suck to get pregnant. Maybe we could find some condoms or something.”

“Yeah.” Condoms instantly shot to the number-one position on my mental list of must-find survival supplies—far ahead of food, water, and a way across the Mississippi.

Darla was quiet for a while.

To break the silence, I asked, “What about you?”

“Sex, you mean? No. I was going to let Robbie McAllister do it. I mean, I was thinking about doing it with him or whatever. We’d gotten pretty hot and heavy, but then he got all pissy about how I was always working on the farm and would never go to the movies in Dubuque with him. So I dumped him.”

“Pretty tough to keep up that farm and have a social life.”

“Yeah.”

Darla was silent for so long, I wondered if she’d fallen asleep. When I was sure she had, she whispered, “You know, there’s plenty of stuff we can do without any chance I’ll get pregnant.”

“Like what?”

“I’ll show you.”

When she reached for my belt this time, I didn’t stop her.

Chapter 40

About an hour after we set out the next day, the road left the ridgetop wood. Below us lay a huge valley blanketed in brilliant snow. On the right side of the valley, high on a hillside, a massive church stood alone. It looked old and imposing, its dark brick bell towers glowering over the snow below it.

On our left, high on the opposing hillside, a second church stared across the valley at the first one. This church was white, limestone or marble maybe, and if possible, even more ornate and imposing than the first. A small town nestled below the second church.

We skied down to where the road we were on teed into a highway. There were two road signs there: Highway 52 and Welcome to St. Donatus. Even from a distance, we could see footprints everywhere in the town’s snow-covered streets. A few of the sidewalks had even been shoveled. Darla and I skirted around the edge of the town. It seemed unlikely that anyone would want to share food with a couple of strangers. And if they couldn’t help us, there was no reason to run the risk that they might try to hurt us.

On the far side of St. Donatus we caught a small, unmarked road that continued east, passing near the white church. As I skied between the two churches, I had the feeling they were looking down on us, blessing our journey. Maybe it was an aftereffect of the night before, but I felt more hopeful than I had since we’d left Worthington.

* * *

By that afternoon, the hopeful feeling had left me. The road, which had been heading steadily east, began twisting unpredictably. Sometime after lunch, I completely lost track of which way we were going. Darla thought we were still heading east, but she also said we should have hit the Mississippi by then. We had only passed two farms, but both were obviously occupied, so we hadn’t found any food.

A bit before dark, Darla spotted a low structure near the road. She skied around it and found an open doorway at the far side.

It was too low to stand up inside the building. The ceiling was about three feet high at one side of the shed and five feet or so at the other. We had plenty of room though: the building was seven or eight feet wide and at least thirty feet long. It reeked of pig crap.

“Sleeping in a pigsty. That’s a new low,” I said.

“It’s a pig barn, not a sty. Pigsties are outdoor corrals. Anyway, it beats sleeping in the snow.”

“I guess. Where are the pigs?”

“I dunno. Dead or in a barn closer to the farmhouse, maybe.”

We ate our last two pancakes. Darla fed Jack from our dwindling supply of cornmeal.

We laid out our bedding in the cleanest-looking corner. I was hoping to fool around some more, but Darla just gave me a quick kiss and rolled over. Maybe she was tired, or maybe eau de pig crap didn’t turn her on. Couldn’t say I blamed her—much.

* * *

Only Jack got breakfast the next morning. I thought about suggesting we cook the last bit of cornmeal instead of saving it for the rabbit, but that would’ve made only one pancake.

The road ended in a T not far from where we’d spent the night. I wasn’t sure which way to turn. I asked Darla, but she was as lost as I was. Her mechanical skills didn’t include directional aptitude, apparently. We turned right, figuring that if we’d generally been heading east, that would turn us south, away from Dubuque.

By lunchtime, we’d been forced to make two more turns. We’d had to guess which way to go each time. The roads were getting narrower and the ditches at the side shallower. Where the road ran through trees, it was easy to follow. Where it ran through open fields, we had trouble. We’d seen no sign of the Mississippi, although Darla said the steep hills here meant we were close.

Lunch was a short rest break and some water. I struggled to think of anything other than food. But my mind returned over and over to corn pone, to the bags of cornmeal I’d left with Katie’s mom. I wondered what Darla was thinking. Giving our food to Katie’s mom seemed more boneheaded by the minute. I remembered desperately scrounging for Skittles in the gas station on Highway 20. How hungry and weak I had been. We needed to find food soon.

Less than an hour later, we came across another farmhouse. It was hidden at the back end of some twisty, no-name road. There was a small, ranch-style house and four big, low sheds, maybe ten feet wide by fifty feet long. Arrayed along the outside of the sheds was a series of big metal silos and tanks connected to the sheds by a system of pipes.

“Pig farm,” Darla said.

I sniffed. The air was cold and clean, with a hint of pinesap from the nearby woods. “How can you tell?”

“Low sheds with silos and water tanks connected to them by an automatic feeder system—it’s a pig farm.”

“No tracks I can see. Check it out?”

“Yeah.”

We skied up to the house. Everything was quiet and still—too quiet. It made me nervous. Darla popped the bindings on her skis. She tried the storm door—it was unlocked, but it wouldn’t open because too much snow had drifted up against it.

I helped her dig out the snow until the storm door would open enough for us to slip through. Darla tried the main door. It was also unlocked, opening with a creak as if it hadn’t been used in a while.

“Who leaves their front door unlocked?” I whispered.

“Lots of folks do. Or maybe whoever lived here wasn’t planning on being gone long.”

We stepped into a small entryway. Beyond, I saw a living room plainly furnished with a battered oak coffee table and a sofa upholstered in worn, striped cloth. A huge limestone fireplace dominated one side of the room.

“Should we call out?” Darla whispered.

“Might as well.”

“Anyone home?” she yelled.

No one answered. I thought I heard a distant thump from outside, but I might have imagined it.

We tiptoed through the living room into the kitchen. A dirty bowl rested in the sink. White fuzz covered it, like the stuff that grows on food left too long in the freezer. Neither the water nor the electric stove worked, of course.

We searched the refrigerator and cabinets. Our whole haul was a box of cream of wheat with about two inches left in the bottom, a three-quarter empty can of Crisco, and four packets of Sweet’N Low. Not much of a meal.

“Where’d the people go?” Darla said softly.

“Dunno. Out to get food? They didn’t have much, that’s for sure.”

“Let’s check the sheds.”

We left the house the same way we’d come in and skied to the closest pig barn. Darla found the entrance: a door so short we’d have to duck to get through. A yellow handle, leaning against the metal wall, protruded from the snow. I pulled it free—it was a full-sized ax with a fiberglass handle and rusted iron head. I looked a question at Darla. She shrugged, and I put the ax down.

I pushed down the lever-style doorknob. I’d only opened the door five or six inches when I heard a grunt, and the door was shoved closed violently from inside. I leapt back, holding my staff at the ready.

Everything was still for a minute. It was quiet, other than the blood rushing in my ears and my heart thumping in my chest. I yelled, “Hello? Who’s there?”

Nothing.

I tapped the metal door a few times with my staff.

No response.

I started to open the door again, cracking it a few inches. A bit of snow fell past the bottom of the door into the space inside. It was too dark inside to see through the narrow opening. I stood and listened for four or five seconds. I heard a grunt and the door slammed again.

“This is weird, let’s move on,” Darla said.

I agreed with her, it was strange. But my hunger was stronger than my fear. “We need food.”

“Maybe we’ll find another place farther on.”

I lowered my voice to a whisper. “Look, whoever’s in there, if it comes to a fight, I need to be able to see.”

“What is it with you and fighting, anyway? Let’s just move on. We’ll find food someplace else.”

“There might not be anyplace else. And we need the food. Look, just give me a hand here.”

Darla gave me the evil eye for a few seconds. “Humph.” Then she dug a candle out of the pack on my back and lit it.

I unlatched the door, opening it a half inch, then stepped back and kicked it as hard as I could. It flew open about a quarter of the way and hit something solid. I heard a squealing noise and a series of thunks like wood hitting concrete, and then the door swung fully open. I ducked my head and charged in, holding my staff in front of me. Darla followed me with the candle.

Inside, the candlelight revealed an abattoir. There were partially chewed hog carcasses everywhere. The floor was slick with frozen blood. Two live pigs were in full flight away from the door, their hooves striking the concrete floor, their heads streaked with fresh blood.

Darla pointed. “Oh. My. God. What’s that?”

I looked. To one side of the room there was a row of pens built with metal pipes. They were all empty. Beside one of them, I saw what Darla was pointing to. A man, or what was left of him, lay alongside the fence. One of his legs was obviously broken: a large yellow-white bone stuck out of his torn jeans, pointing almost directly at us. Half his face and most of his torso had been chewed way. The gnawed white ends of his ribs protruded like skeletal fingers from his chest. “That’s disgusting,” I said, turning away.

“Yeah,” Darla replied. The two live pigs had moved around us, back to the door, while we looked at the corpse. They were lapping at the snow that had fallen into the barn, grunting and slamming into the door and each other in their haste to get fresh water.

“What do you think happened?” I asked.

“This guy ran out of food, came out here with his ax to butcher a pig, I guess. Usually people send their pigs to a processor for slaughter, even if they’re going to eat the meat themselves, so he might not have known what he was doing. Somehow he broke his leg. Maybe the pigs were starving, thirsty, or whatever and crushed him against that fence. Once he bled out, well, pigs will eat anything.”

“Gross,” I said. “Too bad there’s no food in here.”

“Hello? There’s enough food here for both of us to live on for weeks.”

“You want to eat—you can’t be serious.”

Darla kicked one of the pig carcasses. It was frozen solid. “The dead ones would probably be okay to eat. But I was thinking we should butcher one of those.” She pointed at the two pigs licking snow by the door.

“I don’t know—”

“What, you don’t like pork?”

“I like bacon, although it feels kind of slimy getting it out of the package.”

One side of her mouth wrinkled. “City people. Let me see your knife.”

I handed it to her. “You ever butcher a pig?”

“No. But how much worse can it be than cutting up a rabbit?”

It was way, way worse. Darla handed me the candle and retrieved the ax from where I’d left it outside the door. “Any idea what the best way to kill a pig is?”

“What, you don’t know?”

“Um, no. Maybe a whack on the back of the head? Like some people use for rabbits?”

“Gonna need to be a heck of a whack.” These pigs were huge—two hundred pounds or more. “I dunno if that will do it. Hitting a person on the back of the head doesn’t usually kill them—it knocks them out or stuns them.”

“Hmm, okay.”

Holding the ax in a two-handed grip, Darla got alongside one of the pigs. She reversed the ax so the blunt end aimed down and raised it high above her head. The pig kept lapping at the snow, oblivious to the doom poised above it.

The ax fell, thunking onto the back of the pig’s head. The pig went limp and slumped to the ground. The other pig let out a squeal and galloped away, seeking refuge at the far side of the shed.

Darla dropped the ax and grabbed the knife. She plunged it into the underside of the pig’s neck, just above its chest, and pulled the knife upward toward its snout. It woke and thrashed, all four legs churning the air as if it were trying to run away. One of its forelegs caught Darla on her shin and she yelled, “Ow! Crap!” and jumped back, pulling the knife out of the pig’s neck.

Blood fountained out, spraying her arm. The blood gleamed black in the candlelight. A few drops spotted Darla’s face. I felt suddenly ill and turned away. The pig began squealing nonstop, a sound that resembled nothing so much as a kid throwing a full-throated tantrum. We were forced to listen to that awful noise for at least five minutes before the pig finally bled out.

I hadn’t had anything to eat since the day before. Still, when I saw the carnage in the pig shed, I’d lost my appetite. Now I felt so sick, I wasn’t sure whether I ever wanted to eat again. “If we live through this, I’m going to become a vegetarian.”

“Not if I’m cooking for you,” Darla said.

“That’s okay, I’ll do the cooking. Hope you like tofu.”

“Tofu? Now that’s disgusting,” said the girl whose arm dripped with pig blood. “Give me a hand with this.”

Darla and I each grabbed one of the dead pig’s back legs and dragged the carcass outside. It left a wide, red smear in the snow.

I volunteered to build a fire, hoping to avoid butcher duty. By the time I got the fire done, Darla had gutted the pig and was trying to hack the hams free with the hatchet. Her arms and chest dripped with pig blood. I looked down for a moment, trying to get my stomach under control.

“That’s a lot of meat. Won’t it spoil?” I said.

“If we had time, we could smoke it. But I’m guessing you’d rather not hang around here.”

“Right.”

“So I figured we’d try to cook it all and freeze it. If the weather stays cold, it should be fine in our backpacks.”

“Okay. I’m afraid you’ll say yes, but is there anything I can help with?”

Of course there was. So I wound up getting almost as bloody as Darla. It seemed like we wasted a lot of that pig—I left tons of meat clinging to its bones and skin. Darla just shrugged. “Yeah, we’re wasting a ton. But we can’t possibly carry it all, anyway. And this is a lot different than butchering a rabbit. I’m doing the best I can.”

I was wrong about never eating again. The smell of roasting meat brought hunger surging back to my stomach. We ate a late lunch of very thick-cut bacon fried in our skillet over the open fire. Well, Darla said it wasn’t really bacon since it hadn’t been cured, but it tasted similar: juicier and much less salty.

As I reached for my third slice, a thought occurred to me that stopped my hand in midair and brought my nausea back. “Um, so we’re eating this pig . . .”

“Yeah?” Darla replied around a mouthful of pork.

“And this pig ate part of that farmer. Doesn’t that make us cannibals?”