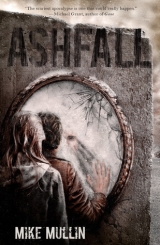

Текст книги "Ashfall"

Автор книги: Mike Mullin

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Chapter 30

I snapped my boots into my skis and shouldered Target’s pack. Darla hadn’t moved.

“We’ve got to go,” I said.

Darla stroked the rabbit.

“Put your skis on and get your poles.”

Nothing.

“Damn it, Darla, we’ve got to go. There’s no shelter here now.” It was probably midmorning by now, and I was feeling antsy. I didn’t know why. The burnt buildings, Target’s body—I wanted to get away from the farm as fast as possible.

But Darla wasn’t budging.

I wanted to scream in frustration, but instead I said as gently as I could, “Put your skis on, now, please.”

Finally, she moved. She transferred the rabbit to one arm and slowly clipped her boots into the skis.

“Pick up your poles.” I tried to take the rabbit from her, but she shied away, clutching it with both hands. I gave up and handed the ski poles to her. She took both of them in one hand, the other still clutching the rabbit tightly against her chest.

I sighed and pushed off powerfully with my pole and staff, heading for the road in front of Darla’s farm. About thirty feet off, I stopped and turned. She hadn’t inched forward at all.

“Come on, Darla. Get moving!” I yelled.

She shuffled out to meet me.

It was excruciatingly slow. Darla held the poles as deadweight in one hand. Twice, the rabbit got unruly, and Darla dropped her poles to cuddle him. The second time, I stopped and strapped her ski poles to the back of my pack.

We made better time then. At least the rabbit wasn’t holding us up—with both hands free, Darla could keep him under control. Better time didn’t mean we made good time, though. Without poles, Darla couldn’t balance as well or push herself along. I had to stop again and again to wait for her to catch up.

I couldn’t keep going this way. I felt terrible for Darla. She’d lost her home, her mother, everything she’d built, and almost all her rabbits. I thought I partly understood how she felt—at that moment I wanted to stop, curl up into a ball, and let someone take care of me again. But even more than I wanted to check out and give my emotional wounds time to scab over, I wanted to live. Neither Darla nor I were likely to survive if we kept heading for Warren at a snail’s pace. So when we reached the intersection where I’d planned to turn east, I turned south toward Worthington instead. Darla followed me.

A couple miles farther on, we skied down a steep hill into a small valley. A creek burbled merrily under the bridge at the bottom of the hill. It had washed away some of the ash from each bank, revealing a few tendrils of sickly yellow vegetation.

I stopped, shrugged off my pack, and sat on the guardrail along the edge of the bridge. As I dug through the backpack, hunting for lunch, I talked to Darla.

“We can leave the rabbit here. There’s water. There are some plants to eat. It’ll be okay.” I didn’t really believe this. That rabbit was dead either way. If it stayed with Darla, she’d probably eat it when she got hungry enough. The plants by the creek looked dead—and there weren’t enough of them to sustain a mouse, let alone a rabbit. I was just hoping she’d give it up, so we could move at a reasonable pace.

“No,” Darla replied.

Okay then, that was progress, I guessed. It was the first word she’d said since we’d left the farm over two hours before. I handed her a strip of smoked rabbit. Lunch.

She held the strip of meat in one hand and the rabbit in the other and sat beside me on the guardrail to eat. The rabbit sniffed the meat and wrinkled its nose—in disgust, perhaps.

When she finished eating, Darla rummaged through the backpack one handed. She came up with a handful of cornmeal and started feeding the stupid rabbit out of her hand.

“What are you doing?” I shouted. “We need that food!”

Darla gave no sign that she’d heard me. I yelled some more, but I might as well have screamed at the ash for all the good it was doing. I thought the rabbits wouldn’t eat corn, but it seemed to be nibbling on it now. Maybe it had gotten so hungry it couldn’t afford to be picky anymore. Anyway, I closed up the backpack and took off, skiing along the road to Worthington.

I got about a half mile ahead of Darla before I felt guilty and stopped to wait. I thought about our other trip to Worthington, just the day before. In places where the road was sheltered from the wind, I could see our tracks in the ash: one set of ski tracks going, with Darla’s deep boot prints running alongside. Two sets of ski tracks returning.

How different that trip had been: Darla riding on my skis down the hills, pressed up against my back, rolling around together in the ash, and playfully hurling handfuls of it at each other.

Eventually, Darla caught up. I never let myself get more than thirty feet ahead of her the rest of the way to Worthington.

The putrid yellow haze in the sky was slowly being replaced by gray twilight as we skied into Worthington. Incredibly, we’d made better time yesterday with Darla walking than we had today with both of us on skis.

I led Darla through town to the school I’d seen yesterday, St. Paul’s. There were ramparts of ash around it where someone had shoveled off the roof. A cleared path led to the front door, but it was locked and dark inside. I banged on the door, but no one answered. Surely this was the right place? Several people had mentioned yesterday that this school was serving as a shelter.

I slogged to the side door next to the gym, with Darla following. These doors were unlocked. I brushed as much ash off my clothes as I could, unsnapped my skis, and stepped inside.

The gym here wasn’t nearly as large as the one at Cedar Falls High, but the scene inside was similar, if a little more chaotic. An elderly woman sat at a desk inside the gym doors, working by the light of a battery-powered lantern. The gym floor was covered with every type of bed imaginable laid out in a grid. There were leather couches, sleeper sofas, futons, cots, a bunch of twin beds, and even a heart-shaped monstrosity—a honeymooner’s red nightmare bed. Some of the beds were surrounded with makeshift enclosures, drapes hanging on rough frames made of two-by-fours, curtain rods, and rope. Most of the drapes were pulled back at the moment, I assumed to allow light into the sleeping areas.

There must have been eighty beds in there, but there weren’t many people in the gym, only the woman at the desk, a couple of adults napping on couches, and a group of very small kids playing Chutes & Ladders on the floor.

I stepped up to the desk. Nobody noticed me. The woman was completely engrossed in a piece of paper that had Duty Schedule printed in block letters across the top.

“Uh, hi,” I said.

The woman jumped halfway out of her chair. She whipped open one of the desk’s drawers and thrust her hand inside. I heard a metallic click, but her hand didn’t emerge from the drawer. I held my hands up by my shoulders, palms open.

“Sorry I startled you,” I said.

“You certainly did, young man. I’m going to strangle Larry.”

That didn’t make sense, but I let it pass. “Darla and I don’t have a place to stay, and we heard this was a shelter. . . .”

The woman removed her hand from the desk drawer and looked at Darla standing beside me. “Darla Edmunds? I heard you were in town yesterday. Heard you and your mother were doing well, all things considered.”

Darla looked away.

“Yes ma’am,” I said. “They were. Doing well, I mean. Yesterday. But Darla’s mom is dead now, and she has no place to stay. I wondered if she could stay here for a while.”

“Gloria’s dead? I’m so sorry. How?”

“Bandits. They’re dead now. Darla and I killed them. But they burned—”

A beefy guy emerged from the locker room and ran to the desk. “Sorry, Mrs. Nance. I think it’s all this corn. Gives me constipation—”

She cut him off with a glare and struck through a name under “Security” on her duty roster. She wrote “Larry Boyle” in a column labeled “K.P.” Larry slunk off toward the gym doors. Mrs. Nance turned back to me, “Of course you can both stay here. You’ll need to work—everyone’s expected to do something. I’ve heard Darla’s a wizard with machines. There’s a crew trying to rig some of the old farm windmills to recharge batteries. That suit you, Darla?”

Darla didn’t reply.

“Yes, that sounds fine,” I said.

Mrs. Nance frowned but made a note on her roster. “And your name, young man?”

“Alex.”

“Are you particularly good at anything?”

“Not really.”

“Field duty then, digging corn. You look strong enough.”

“If it’s okay, I’d been planning to move on tomorrow. My family, they’re in Warren, Illinois. At least I hope they are.”

Darla turned her head and stared at me then. She had an expression on her face that I found impossible to interpret.

“Lot of lawless country between here and there,” Mrs. Nance replied. “And where are you planning to cross the Mississippi? I hear there’ve been riots in Dubuque.”

“Yes, ma’am. I’d noticed—about the lawless country, that is. And I hadn’t thought ahead about crossing the river.”

“Where did you come from?”

She teased the whole story out of me. I didn’t really want to talk about it. I tried giving her one-word answers, but she kept asking me questions, and gradually I gave her the whole story. My room collapsing in Cedar Falls. The three guys trying to invade Darren and Joe’s place. My lonely trek across northeast Iowa. When I finished, Mrs. Nance shook her head. “That’s quite a story, young man. I can offer you dinner tonight and one night’s lodging. I wish I had supplies to spare to help you along, but we have our hands full here.”

“I understand. And thank you,” I said.

“I hear FEMA is in Illinois. Maybe you can find some help there. There are no relief supplies for this side of the Mississippi yet, although I understand the politicians in Washington have figured out that this is a disaster area and declared it so.” Mrs. Nance laughed, a short sharp sound halfway between a bark and a sob.

* * *

Dinner that night was thin corn porridge. Everyone filed into the school cafeteria shortly after nightfall. About seventy people were staying at the school. Most of them arrived for dinner covered with ash; they’d been digging corn all day.

Darla carried the stupid rabbit into the cafeteria with her. She got a few strange looks, but mostly people seemed too tired to care. I saw her sneak two spoonsful of porridge to the rabbit. I don’t think anyone else noticed. There might have been trouble if they had. The portions were small enough without sharing food with a rabbit that would itself have made a nice meal.

The good beds were all claimed, of course. I’d been hoping for the leather couch or maybe that enormous heart-shaped bed, tacky as it was. An old, wiry guy stretched out on the couch, and a mother shared the heart bed with her three young kids. Darla and I got twin mattresses on the floor near the gym door.

Darla flopped fully clothed onto her mattress, on top of the blanket. She held the rabbit against her chest. I hoped it would wander off in the night.

I stripped off my outer shirt, boots, and jeans and crawled under the blanket. A little girl flickered through my memory—the girl who had tried to steal crackers from me while I slept at Cedar Falls High. I pulled my backpack up onto the mattress next to me and flung one arm over it.

“Goodnight, Darla.”

Nothing.

Chapter 31

Someone moving nearby woke me. I looked around—about half the people in the gym were up, preparing for the new day. Darla still slept. The rabbit lay snuggled against her side.

I got dressed as quietly as I could. My right ankle was bruised and swollen. I had to grit my teeth and strain to force my boot over it. I stood carefully and shouldered my backpack. Mrs. Nance was up already, working at her desk.

“Thanks for letting me sack out here,” I told her.

“You’re welcome,” she replied. “Breakfast will be served in the cafeteria in about ten minutes. You may join us if you wish.”

“I’d better get going. I’ve imposed on your hospitality enough. Thanks again.”

“Take care, young man.”

I paused to look back at Darla. She looked small, alone on the mattress in the big gym. It felt wrong, somehow, to leave her there. I knew I’d miss her terribly. But my mind insisted it was right—she’d be safer here with people she knew, people she’d grown up with, than she would be with me, risking whatever dangers awaited on the road to Warren. And unless . . . until she recovered from the trauma of her mother’s death, she couldn’t move fast enough to travel, anyway. I turned away.

The temperature had dropped further overnight. My breath left clouds in the air, and I shivered as I snapped into my skis. I wasn’t dressed warmly enough for the weather. I figured I’d be okay so long as I kept moving, but if I had to sleep in the open, it would be a problem.

I skied two blocks north and turned right on First Avenue, heading east. First Avenue became East Worthington Road. I set a fast pace, thrusting my feet forward and pushing off strongly with my poles. Outside town, there was a long, gentle upward slope. I took the whole thing without having to duck walk or side step. Moving felt good—I put everything I had into it, trying to keep my mind on the skiing. It beat thinking about Target, or Mrs. Edmunds, or my family . . . or Darla.

At the top of the hill I stretched and looked around. There was no wind, and the day seemed clearer than any since the eruption. It was still dim, like a very dark and overcast day, but there was a bilious tinge to the sky.

Ahead of me the road ran straight down a long, gentle slope. Along either side, a few lonely cornstalks poked through the ash. I looked backward. My passage had left a trail of ash hanging in the quiet air that led back to the edge of Worthington, barely visible in the distance.

There was another puff of ash there. A tiny figure on skis had left Worthington, moving east toward me. There was only one other person I’d seen skiing since I left Cedar Falls. I flopped sideways, sitting in the ash to wait. I wasn’t sure whether to groan or cheer as I watched her slow progress up the hill toward me.

It took Darla almost a half hour to reach me. She was carrying the stupid rabbit under one arm. Her ski poles were dangling from her other hand, utterly useless.

“What the hell are you doing?” I asked as she skied up to me.

She didn’t reply.

“You don’t have any supplies; you’re not dressed for the cold. . . . What if I hadn’t seen you following me? You could die out here!”

Nothing.

“Go back to Worthington. You’ll be safer there. Those people know you. They like you. I’m headed for God knows what. I’ll probably be dead in a week.”

She didn’t move.

“Will you at least let that stupid rabbit go?”

She clutched it tighter against her chest.

“At least we’ll have something to eat when we run out of food.”

She eyed me sullenly, scratching behind the rabbit’s ears.

“Crap.” I thought about the problem for a minute. I could easily outdistance her, leaving her in the dust. But if she followed me east, she’d die for sure. She had no food, water, or bedding. And truth be told, there was a small lonely voice inside me—a voice I’d been trying to suppress—that was mighty glad to see her. I shoved violently off the ridge top, skiing back toward Worthington.

I made great time going back down the slope. I pushed with both poles and shifted my weight from ski to ski, hurling myself forward with a skating motion. When I got to the outskirts of Worthington, I looked back. Darla was less than a quarter of the way back to town, following me. I skied down First Avenue and took a left on Third, returning to St. Paul’s gym.

Mrs. Nance was working at her desk. “You’re back? I didn’t expect to see you again.”

“Yeah, I didn’t expect to be back. Look, do you know anyone who has an extra backpack I could trade for?”

“We’ve got a few here—I can’t spare any of the big ones, but I could part with one of the book bags.”

She lit a candle and led me down the hall to a classroom. It had been converted into a giant supply closet. There was an amazing assortment of junk stacked in the room: six old mattresses, two red children’s wagons, a stack of two-by-fours of various lengths, and piles of clothing, among other things.

We stopped at a table, one end of which held about a dozen small backpacks. I sorted through them and checked their zippers. Most of them had those cheap plastic zippers that always break halfway through the school year. I figured anything that couldn’t make it through a school year wouldn’t be good for a week out there in the ash. I chose the larger of the two that had metal zippers and asked Mrs. Nance what she’d take in trade for it.

Yipes, but she was a nasty bargainer. What was it with Worthington women, anyway? Maybe there was a Negotiate Like a Shark Club in town and Mrs. Nance and Rita Mae were founding members. I wound up giving her two smoked rabbit loins, a haunch, and a bag of cornmeal for that dumb backpack. By the time I got back outside, Darla was there, waiting for me.

I got a blanket out of my pack and jammed it into the bottom of the school bag. Then, thinking about my plan, I packed the plastic tarp over the blanket. Rabbit poop protection. That filled about half the small pack.

I grabbed the rabbit. Darla pulled it to her chest. “Let go. I won’t hurt it,” I said.

She released the rabbit. It began squirming, but I managed to jam it into the backpack on top of the tarp. I closed the zipper on it, leaving a two-inch gap so the stupid thing could breathe. Not that I cared much if it suffocated.

“Here.” I held the backpack up so Darla could slip it over her shoulders. “Try to keep up, okay?”

She didn’t reply, so I set off, following the four sets of ski tracks we’d already made that morning. The light outside had dimmed while I was inside St. Paul’s. I glanced up. Gray tendrils crawled across the yellow sky, clouds presaging a storm, perhaps. But they looked like no clouds I’d ever seen.

My thoughts were as confused as the sky. Leaving Worthington the first time, I’d already started to feel Darla’s absence, a dull ache as inescapable as a broken tooth I just couldn’t quit poking with my tongue. So I should have been happy now, right? Only I wasn’t. As I pushed my skis forward—shh, shh, shh over the ash—the gray-and-yellow sky settled on my shoulders like a heavy blanket.

I spent several minutes thinking about it before I figured out the source of my grim mood: fear. Right or wrong, I already felt somewhat responsible for her mother’s death. What if following me got Darla killed, too?

Chapter 32

It got colder throughout the day. When we stopped for lunch, I was surprised to find that the water bottles I’d packed in the outside pockets of my backpack were partially frozen. After we ate (cold strips of smoked rabbit meat), I repacked everything so that the water was inside the pack, against my back. Hopefully that would keep it liquid.

Now that she didn’t have to hold the rabbit, Darla kept up easily. She probably could have passed me—she was in way better shape than I was—but she skied behind, matching my pace.

I started searching for a place to spend the night about midafternoon. There were farmhouses along the road every half mile or so. The first three we passed had tracks in the ash between the outbuildings and the houses. Probably the people in them would have been friendly and let Darla and me hole up in one of their barns overnight, but I was tired of people and their stupid guns. I skied on.

The fourth place we came to was obviously uninhabited, obvious because the house, barn, and garage had all collapsed. The only intact buildings were two concrete grain silos. I slid twice around both the cylindrical silos, looking to see if we could get inside, but there was no visible entrance. There must have been some way to get in-they’d be useless if the farmers couldn’t load them with grain. Maybe Darla knew how they worked, but she still wasn’t talking.

The barn had stood next to the silos, but it was hopeless. The ash had flattened it completely—panels of wood siding and rafters jutted randomly from the heaped wreckage.

The front part of the farmhouse was standing, sort of. The whole back section and roof had collapsed, pulling the front wall backward so it leaned precariously at about a sixty-degree angle. I didn’t want to get near it for fear it would fall on us.

A big metal garage had stood not far from the house. The roof and walls were down, but something was supporting the wreckage in the middle. I crawled under a bent wall panel to check it out but couldn’t see anything inside. I had to duck out, fish a candle out of my pack, and try again.

There was a huge John Deere tractor inside, a combine, I guessed. It supported the wrecked roof, creating a triangular area big enough to walk around in. It seemed safe enough; certainly the tractor wasn’t going anywhere. And finding a sheltered spot to spend the night was a huge relief. At least we wouldn’t freeze to death—not tonight, anyway.

I led Darla in and built a fire beside the combine, using scraps of wood from the fallen barn. It’s a lot harder to cook over a fire than you’d think. I made corn pone. Some of it was a bit burnt, but Darla ate it, and she hates corn pone, so maybe it wasn’t too bad. Either that or she was starving. She got some cornmeal from my pack and tried to feed her rabbit. It didn’t eat much.

We laid our blankets next to one of the tractor’s huge rear wheels. The concrete-slab floor was cold, but at least we were out of the wind. “Goodnight,” I said, as Darla lay down beside me. She didn’t reply, just rolled over to face the oversized tire. I pulled my backpack close to use as a pillow and rolled onto my left side, facing away from her.

* * *

When I woke up, Darla was pressed against my back, one arm flung over my hip. It made me feel warm being spooned together. Her body heat was almost enough to counteract the chill radiating up from the cement floor. I lay as still as I could, trying to enjoy the quiet morning and the comfortable weight of her arm on my side.

The first sign I had that Darla might be waking up was when she pulled her arm tighter around me, snuggling closer. Maybe she came fully awake then, because a few seconds later, she yanked her arm back and rolled away.

We ate a cold breakfast and packed in silence.

* * *

It started to snow later that morning. Fat flakes drifted lazily down and clung to our clothes for a while before melting. At first it was great. As the snow began to accumulate on the road, our skis slid more easily. Pretty soon we were moving faster than I had since leaving Cedar Falls.

But the wind picked up and the snowfall got heavier. It got steadily more difficult to see. The wind snapped at the left side of my face, whipping icy particles into my eyes. I wished I still had Dad’s ski goggles, but I’d lost those when Darla’s house burned. Darla and I weren’t dressed for this kind of weather. When we stopped for lunch, I started shivering uncontrollably.

Darla’s lips and nose were tinged blue. Her hands were jammed into the pockets of her jeans, but I saw her shoulders quivering. I had a hard time repacking our lunch stuff because my hands shook so badly.

I set a fast pace, trying to warm up. The blizzard got worse. I skied by the edge of the road, looking for mailboxes or any sign of a place to stop and find shelter. Twice I veered off the road accidentally and had to sidestep laboriously out of the ditch.

We’d been skiing up a gradual incline for a while. Suddenly the slope changed, and I picked up speed, heading downhill. I assumed we had climbed a ridge and were starting down the backside now, but I couldn’t see it. I could barely see the tips of my skis.

I accelerated dangerously. The wind and snow whipped at my face, turning the world blindingly white. I tipped the backs of my skis outward, forcing them into a downward-facing vee, trying desperately to slow my descent. I hoped Darla wouldn’t run into me. For that matter, I hoped she was still behind me. I couldn’t hear anything over the howling wind, and I was so focused on trying to stay on the road that I couldn’t risk a backward glance.

I leaned forward and squinted, trying to see the road ahead. Tears leaked from my wind-burnt eyes and froze on my cheeks. We had to find a place to stop, but I couldn’t spare the attention to look—it took everything I had just to stay upright and on the road.

The edge of an aluminum guardrail appeared suddenly in front of my skis. I screamed and threw my weight to the right, trying to avoid a collision. My left ski clipped the guardrail. I slid down an embankment, totally out of control now, flailing my arms in an effort to stay upright.

Branches clawed at my arms and legs, breaking as I crashed through. A tree limb slapped my face, leaving a stinging line across my frozen cheek. My ski tips caught on something, and I pitched forward as my boots popped free of the ski bindings. I fell into darkness.