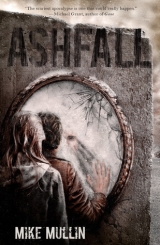

Текст книги "Ashfall"

Автор книги: Mike Mullin

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Chapter 43

The guards weren’t the least bit gentle when they tossed us through the gate. I fell on my face in the packed snow. I pushed myself upright on arms that still trembled from the fight, wiped the ice off my cheeks, and looked around.

The first thing I noticed was how many people were there. This place was crowded. Old, young, families, individuals, white, Hispanic, black—the only thing everyone had in common was that they were all dressed in dirty, ragged clothing. I hadn’t seen so many people in one place since the eruption; in fact, I hadn’t seen a crowd like this even before the volcano.

The second thing I noticed was the camp’s size. We were on a relatively flat ridgetop. The fence stretched three hundred or four hundred yards in each direction before it reached a corner. It was chain link, like all the fences we’d seen here, twelve feet high and topped by a coil of razor wire.

A thin guy with a dirty gray beard reached for my backpack. I shoved his hand away and grabbed our packs. He slunk off into the crowd.

Inside the fence, the snow had been churned to a dirty, frozen slush by thousands of feet. Outside, a smaller fenced area contained four large white canvas tents—the admissions area we’d come through. Beyond that, I saw the highway.

There were green canvas tents in ragged rows inside the camp. A few of them were erected on raised wooden platforms, but most were pitched directly on the cold ground. Almost all of them were closed, flaps tied tightly against the wind. The tents that weren’t closed were full, each packed with a dozen or more people.

A loudspeaker mounted on a nearby fence post crackled to life. The sound was distorted and overly loud: “Mabel Hawkins, report to Gate C immediately. Mabel Hawkins, Gate C.”

A narrow strip about five feet wide just inside the fence was clear of people. Darla walked into the clear area and I asked her, “You sure it’s safe? What if that fence is electric?”

“It’s fine,” she replied. “You can’t electrify chain link directly—it’d just ground out. If this were electric there’d be insulators and extra wires. She slapped the fence to prove her point. Then she squatted and reached into my pack, inventorying the contents.

They’d taken almost everything. Our skis, food, rope, knife, and hatchet were all gone. All we had left was our clothing, blankets, plastic tarp, water bottles, frying pan, and a few matches.

Darla snatched the frying pan and hurled it at the base of the fence. It hit with a dull clank and came to rest a few feet away. “Christ!” she yelled. “They took goddamn everything.”

A nasty purple bruise was spreading across the side of Darla’s face. I touched it as gently as I could, trying to figure out if the guards had broken any of her bones. “That hurt?” I asked.

“The pork, the wheat, our knife, and the hand-ax—what the hell do the guards need with that crap, anyway?”

“I don’t know.” I kept probing her cheekbone. It didn’t seem broken, but I wasn’t sure.

Darla slapped my hand away. “Quit messing with my face. It’s fine. And Jack, what was the point of killing him? He survived silicosis, a burning barn, the blizzard, and a long trip in a backpack just to be shot by some asshole guard? Why? I just don’t get it.”

“I don’t know.” I tried to give her a hug, but she pushed me away and started ramming stuff back into my pack. At least our backpacks had plenty of extra room now. Darla stuffed her pack inside mine.

I squatted on my ankles, resting my back against the fence, and Darla squatted beside me. Her hands were on one of the backpack straps, crinkling it into a ball and releasing it, over and over, in barely restrained fury.

“We’ll get out of here somehow,” I said. “What’s a twelve-foot fence and coil of razor wire to us, after everything we’ve been through?”

“Why pen us in at all? I feel like a pig on the way to the slaughterhouse.”

“I don’t know,” I repeated. “We’ll find a way out.”

“Yeah, they’re going to regret the day they locked us in here.” Darla’s eyes had narrowed to a hard squint, and she was scowling.

A pair of guards patrolling along the outside of the fence walked toward us. As they approached, one of them yelled, “Hey, you! No leaning on the fence.”

I ignored him. When he got close enough, he kicked at my back through the chain link. I saw it coming and scrambled away, but not quite fast enough. His toe caught me in the small of my back.

“Asshole,” Darla said aloud.

The guards laughed.

It was getting late, and neither of us had any idea where we’d sleep. But more urgently, we hadn’t used the bathroom since we’d been picked up on the road hours ago. Darla stopped a kid who was hurrying by and asked him where the restrooms were. He pointed, then twisted free of her grasp and ran off.

We walked for a long time in the direction the kid had pointed without seeing anything resembling a latrine. It was slow going, picking our way around knots of people. Some were huddled in groups, talking or just shivering together. Others lay on the ground, wrapped in blankets and pressed against their family or friends for warmth. Every now and then we passed someone who was alone. Most of the loners looked dead, frozen to the ground where they lay, but when I got too close to one of them, his eyes popped open and he glared, warning me away.

We smelled the latrine before we saw it—although calling it a latrine was far too generous. Beside the far fence, a long ditch had been dug, about twenty-four inches wide and eighteen inches deep. Ten or eleven people squatted along its length, doing their business in front of God and everyone.

The other problem, besides the complete lack of privacy, was the lack of toilet paper, sinks, or soap. Sure, Darla and I hadn’t been too particular about those things as we traveled, but this was different: Thousands of people were using this ditch as a public restroom. I glanced up and down the line. Two people had brought their own toilet paper, but others were using newspaper or handsful of snow to clean themselves. Darla turned away and put her hands on her knees.

“You okay?” I asked her.

“Yeah. A little nauseous. I’ll be okay.”

I shrugged and stepped up to the ditch. I don’t like going in public—even the rows of urinals without dividers at school used to bug me. So it took me awhile. But when I zipped up and left the stench of the ditch, Darla hadn’t moved.

“You sure you’re okay?”

“No, I need to pee.”

“Well?” I shrugged.

“I can’t squat over that thing without taking my jeans off. And there’s nothing to lean against.”

I understood what she meant. When she had needed to pee on the road, she’d find a tree to lean her back against and pull her jeans just partway down. I’d never, um, watched the whole process of course; I’m not that pervy. But I’d seen enough to get the general idea of how it was done. “Come on. I’ll be your tree.”

So I stood on one side of the ditch, and Darla stood on the other. She leaned her back against me and pulled her pants down just enough to do her business. I tried not to watch, but there was no point. Hundreds of people were within eyesight, and Darla wasn’t the only woman squatting over that ditch.

“Well, that was humiliating . . . and disgusting,” Darla said as she pulled up her pants.

“Nobody was really looking.”

“You’re not helping.”

“And you’re not the one who got splashed.”

“Oh. Sorry.”

“No worries. It’s only a little bit on my boot. Goes with the territory when you volunteer to be a tree.”

It was getting dark. I was hungry, but we hadn’t seen any sign of food since we’d been thrown into the camp. I was more worried about finding a safe place to sleep. It would be a cold night if we couldn’t find shelter of some sort.

At first, we wandered from tent to tent. But every tent was full, and just touching the flaps often brought shouted curses and threats from within. Some of the tents even had people posted outside guarding them. Other refugees clustered on the lee sides of the tents where they’d be protected from the wind. We might have done that, too, but all the good spots had been taken already.

“I’ve got an idea,” Darla said. “Follow me.”

She led us directly into the teeth of the wind, which had picked up as darkness fell, making it harder and harder to see. It started snowing—hard, icy pellets that stung as the wind whipped them against my skin. I shivered, remembering almost freezing to death under the bridge just a week before. Several times we stumbled over people lying on the ground, made invisible by the snow and darkness.

Darla led us all the way across the camp. The wind was fiercer here with nothing but a chain-link fence to block it. A few tents were scattered on this side of the camp, all of them full, of course. Darla trudged toward one that was built on a low wooden platform. The lee side of the tent was packed—people lay pretty much on top of each other in a long V shape, trying to escape the wind’s nip and howl.

We walked to the windward side of the tent. For the first time since we’d arrived, we were alone. Everyone was avoiding this, the most exposed spot in the whole camp. I didn’t see any reasonable place to sleep—hopefully Darla knew what she was doing.

Snow had drifted against the tent platform. Darla dug a trough in the snow against the tent. It was less than two feet wide and a foot deep, but it would hold us both. She lined the snow-ditch with our plastic tarp and blankets. Then we lay down and wrapped the tarp and blankets over ourselves.

At first, it was terribly cold. But as we lay there shivering and hugging each other for warmth, the snow began to blow up over us, covering our tarp. After an hour or so, we were completely buried and toasty warm. I drifted off to sleep.

I woke up once in the night, feeling sweaty and claustrophobic. I stretched my arm out over my head and poked a hole in the snowdrift. The icy air smelled sharp and relieved my sense of confinement. Darla murmured something in her sleep and pressed herself even tighter against me.

The next time I awoke, it was to the gentle pressure of Darla’s lips against mine. I returned her kiss, getting more and more into it until it occurred to me that I probably had terrible morning breath. Still, Darla tasted fine, and she wasn’t complaining. . . . I broke off the kiss, anyway.

“We should get up,” she said. “I heard voices a while ago.”

“Is it morning?”

Darla reached out and reopened the hole I’d made during the night. A spot of light hit my face. “Guess so.”

We unburied ourselves from the snowdrift. It would have been a beautiful day if there’d been any sun. The snow and wind had died down during the night, leaving behind a thin white blanket that temporarily hid the camp’s ugliness.

We packed our bedding and scouted the area. Nobody was around; the tents were empty, and the dog piles of people sleeping at the lee side of each tent were gone. Paths beaten in the snow led away from every tent. Strangely, all the trails ran parallel. Every single person had gotten up and walked, zombie-like, in the exact same direction. We’d slept through it all.

Curious, we followed one of the paths. It was almost perfectly straight, except for an occasional swerve around a tent. After a quarter mile or so, the paths started to blend into each other so that all the snow was pocked with footprints. There was no longer a discernable trail to follow, but we kept walking in the same direction.

We’d seen only one person along our route, a woman about my mother’s age in the snow beside one of the tents, curled into a fetal position, unmoving. Her hands and feet were bare and tinged blue. I walked over to her, ignoring Darla’s glare, and put my hand against her neck. It was cold and lifeless.

I stood and took a deep breath. The icy air entering my lungs brought something else with it: a wave of sadness so intense I had to close my eyes and fight to hold back tears. That woman could have been my mother. I felt Darla’s arms around me. “You okay?” she said.

“Yeah . . . no.” My sorrow dissolved in a wave of pure fury. What kind of place was this, where tens of thousands of people were herded together without adequate shelter, without decent latrines? A cattle pen, not fit for humans. And the guards, Captain Jameson, they were people just like me. For the first time ever, I felt ashamed of my species. The volcano had taken our homes, our food, our automobiles, and our airplanes, but it hadn’t taken our humanity. No, we’d given that up on our own.

A little farther on, I heard a dull roar that slowly increased in volume as we walked. We rounded a tent and found the source of the noise—a huge crowd, thousands upon thousands of people pressed together in a mob that stretched as far as I could see to both my left and my right.

We stepped to the back of the crowd. It sounded worse than the high-school cafeteria used to at that moment when everyone had finished eating and a few hundred shouted conversations were going on simultaneously.

Darla tapped some guy on the back and yelled, “What’s going on?”

He turned and shouted back, “New here?”

“Yeah.”

“Chow line.”

“Slop line, more like it,” someone else yelled.

Slop mob would have been an even better description. There was no organization that remotely resembled a line. But we hadn’t eaten anything since lunchtime yesterday, so we settled into the back of the crowd to wait.

After a while, we saw people forcing their way out of the mob. They had a terrible time of it—everyone else was pressing forward into any open space. But the folks trying to leave shoved and jammed their elbows into others, eventually managing to worm their way out of the crush. I noticed something odd: all the people leaving had a blotch of blue paint on their left hands. A few of them were carrying Dixie cups, but nobody had any food.

We waited in the mob for more than two hours before I got close enough to see. The crowd pressed forward toward a fence. Beyond the fence stood a series of field kitchens, something like what the Lion’s Club used to set up every year at the Black Hawk County Fair. Dozens of small hatches had been cut in the fence at about chest height. Guys in fatigues were manning each hatch. I watched a refugee fight his way up to the fence. When he got there, he held out both hands. The guard spray-painted a blob of blue on the back of his left hand and put a Dixie cup in his right. The refugee wolfed down the contents of the Dixie cup before he’d taken more than two steps from the hatch, eating with his fingers. I couldn’t see what he was eating.

It turned out to be rice. Bland, white rice—and not much of it. The paper cups held maybe eight ounces, and they weren’t full. I squeezed the rice into my mouth. When I finished, I tore the cup in half and licked the inside. I was still hungry; we’d waited most of the morning for barely enough food to satisfy a robin.

As we walked away, I saw a kid, maybe eight or nine years old, sitting on the ground, furiously scrubbing his left hand with snow. It was raw and red, but the blue paint clung to it in stubborn patches. As I watched, he scrubbed too hard, and a trickle of blood seeped out of the back of his hand, staining the snow red.

“What’re you doing?” I asked.

“Trying to get seconds,” the kid said. “It’s useless, they won’t feed you if your hand’s bleeding.” He looked as if he might cry.

“When is lunch?”

“Lunch? Are you crazy?”

“Dinner?”

“You could try the yellow coats. But you’re probably too tall.”

“Too tall?” Darla said. “What do you mean?”

The kid jumped to his feet. Darla tried to grab his arm but missed. He ran off.

Chapter 44

We spent what little remained of the morning exploring the camp. The main area, where we and all the thousands of other refugees were fenced in, was about a half-mile square. At the south side, between the camp and the highway, were three separately fenced areas: First, the admissions area where we’d entered the camp, which also contained tents for barracks and administration. Second, a vehicle depot that held three bulldozers, a front-end loader, a bus, and a whole bunch of trucks and Humvees. And third, a small area dotted with little sheds that looked like doghouses.

The latrine ditch we’d used the night before was in the northeast corner of the camp, as far as possible from the admin area. Along the west edge of the camp, we found a row of five water spigots attached to wood posts. People were filling every kind of container imaginable. Ice coated the ground around the spigots.

The kitchens were also at the west end of the camp. They were closed and quiet now, except for one. About a dozen people in yellow parkas worked there.

Darla and I walked along the north edge of the camp. There was nothing beyond the fence here except the path the guards patrolled, an open space, and then the woods that began at the edge of the ridge.

“I don’t think it’d take long to run to those woods from here,” I said.

“Yeah. That coil of razor wire on top of the fence is a little bit of a problem, though.”

“The captain said our names would be published in the roster—if my folks see it, they’ll come.”

“Yeah. I’d rather have a good pair of wire cutters than a promise from that captain.”

“Did he even take down our names?” I asked.

“You know, I don’t think he did,” Darla said. “Bastard.”

“I wonder if there’s any way to call my uncle or send him a letter? Or if the captain would let us, even if there were?”

“Doubt it. For now let’s go back to where those guys in the yellow coats were cooking. At least it smelled good there.”

By the time we got back across the camp, there was a line in front of the yellow coats’ kitchen. It was very different from the mob that morning—this was a fairly straight, orderly line with a few hundred people in it. Strangely, almost all of them were kids. There were a few mothers with babies up front and some kids with parents, but the line was mostly little kids by themselves. They weren’t playing or fighting the way kids did at restaurants when their parents weren’t paying attention. Some of them hung their heads, and some were sitting in the snow—on the whole, they looked miserable.

Two of the yellow coats were inside the fence with us. They moved along the line, talking to a kid here and there. When they got close to where Darla and I stood, I could read the writing on their coats: Southern Baptist Conference.

One of them approached us, a woman a few years older than my mom, with long, auburn hair. “You two can move up, you know.”

“I don’t want to cut,” I said.

“It’s not cutting. The line’s organized by age. Well, that was the original idea, but it didn’t work out, so we changed it to height. Come on.”

We followed her to a spot about fifty places farther up. It was the first time I could remember being glad I wasn’t very tall. Darla could have moved another twenty or thirty places forward, but she wanted to stay with me. The woman in the yellow coat moved on, chatting and organizing the line.

About fifteen minutes later the line began to jerk forward. Closer to the front, I saw a crowd of kids eating stew: black beans and ham served in Styrofoam bowls with plastic spoons. The acme of luxury—well, compared to breakfast.

The same two yellow coats were inside the fence, watching the crowd. Outside the fence, the rest of the yellow coats were serving the soup or cleaning up. Two guards in fatigues stood out there, too, looking bored.

We were about fifty feet from the front when everyone lurched to a halt. A low chorus of sighs floated down the line and then it dissolved—all the kids wandered away at once.

I found the auburn-haired woman I’d talked to earlier. “What’s going on?”

“I’m sorry,” she said.

“Why’d everyone leave?”

“We’re out of food. Well, actually, we have food, but we’re rationing it, trying to make it last until the next shipment comes in. Even with as little as we’re serving, we’ll run out completely by next week if the truck doesn’t come.”

“Oh.”

“I trust—I have faith that God will provide. But everyone’s saying this winter may last for years. Food prices have skyrocketed. Everyone’s hoarding. The Baptists are one of the only churches still doing disaster relief, because we’ve been doing it for years. We were better prepared.”

“So when is dinner?”

“You are new.”

“Got here yesterday.”

“The camp quit serving dinner almost two weeks ago. They don’t have enough food, either.”

“We’re supposed to live on one measly cup of rice a day?” Darla said.

“For now. Our pastor is doing everything he can to find donations and to pressure FEMA to bring in more supplies.”

We’d gone from a backpack stuffed with pork to this? I clenched my fists. Sure, some people might think we’d stolen the pork, but we’d worked hard butchering and roasting that pig. I’d never imagined that FEMA would make our food situation worse. But it obviously wasn’t this lady’s fault. I muttered, “Okay. Thanks,” and turned to leave.

The woman caught me with a hand at the waist of my coat. “Trust in the Lord. You never know what He might put in your pocket.” She met my eyes briefly then walked away.

Darla wanted to check out the vehicle depot again, so we meandered in that direction. We’d gotten just inside the first line of tents when someone bumped into my side, almost knocking me over.

Darla yelled, “Alex!” but I was already side-stepping to regain my balance. I glanced to my right—a tall, wiry guy was trying to thrust his hand into my coat pocket. I grabbed him by the hand and spun, twisting his wrist and arm as I went. The move ended perfectly, with me behind him and to his left, controlling his outstretched arm. I kept pressure on his wrist with one hand and launched a knife-hand strike at his neck with the other.

I didn’t know why I chose that strike. I could have kicked his knee, broken his elbow or wrist, or done any number of less lethal moves. The guy was yammering something and trying to pull away. I checked my strike at the last possible moment and only tapped his neck.

“Ah! Crap, man. I was only looking for some food!” the guy yelled.

I let go of his arm, and he ran, rubbing his wrist.

We hadn’t gone twenty feet before another guy planted himself in my path. “Got a proposition for you,” he said.

“I don’t have any food.” What the hell was it with this place? Couldn’t I take a walk without people bugging me at every other step?

“I saw you handle that guy.”

“I didn’t hurt him.”

“Yeah, but you could have.”

I shrugged.

“We’ve got a place in our tent. Eight inches. You stand guard for three hours each night, you can sleep there.”

“Eight inches?”

He gave me a condescending look and started talking more slowly. “A safe place to sleep. Eight inches wide by six feet long. In a platform tent. The best kind. All you have to do is help guard it at night.”

“I need two spots. She’s with me.” I gestured at Darla.

“Can’t do it. I just have one. Only have that ’cause Greeley died last night.”

“Forget it then.” I turned my back to him.

“Wait a second,” Darla said. “We’ll take the one spot. Alex will stand guard half the night, and I’ll watch the other half. If another spot opens up in the tent, we get it, and we switch to the three-hour guard shifts you proposed.”

“You know kung fu, too?” the guy asked.

“It’s taekwondo,” I said.

“Yeah, I know it,” Darla said. “I only know one move, though. Anything happens, I wake him up, and he beats the crap out of whoever’s messing with your tent. Okay?”

“Works for me.” The guy showed us the tent and told us to be back at dusk.

* * *

We spent the rest of the afternoon watching the vehicle depot through the fence. I already knew Darla was weird, but this clinched it. She could spend an entire hour staring at a parked bulldozer. Every now and then she’d ask me a nonsensical question, something like, “Do you think that’s an auxiliary hydraulic system under those lifters?” Or “What kind of tool do you suppose they use to disengage the keyed link in that track?” The only response I could figure out was to shrug and grunt.

It wasn’t all bad, though. I could spend an entire hour staring at Darla. Not that there was anything all that thrilling about either of us right then. We were tired, hungry, and wrapped in multiple layers of filthy winter clothing. None of that mattered to me; I was in love. I thought Darla was, too—but maybe with the bulldozer.

We’d been standing there awhile when I jammed my hands into my coat pockets to warm them. Something was in my right pocket—I took off my glove to investigate and found a handful of almonds.

“Check that out.” I held my hand open against my chest so only Darla could see.

“Those were in your pocket?”

“Yeah.”

“So that’s what that lady was talking about—God will fill your pockets and all.”

“Guess so. Nice of her to sneak us some dinner.” I split them up and handed Darla her share: six almonds.

“Some dinner. More of a snack. Beats not eating, though.”

“Yeah,” I replied, munching surreptitiously on my almonds.

* * *

That night I asked Darla to take the first guard shift. I figured she’d do a better job than I could deciding when to wake me up. I’ve never been very good at judging time, and without the moon or stars, I’d be hopeless.

I stretched out in my eight inches of floor beside the door. I was nestled against an old woman—Greeley’s wife, I thought. I used my backpack as a pillow so that nobody could take it without waking me.

It wasn’t too bad, being packed into the tent like that. Sure, it was uncomfortable; I couldn’t roll over without knocking knees and elbows with my neighbor. And it smelled bad, since nobody had showered in weeks. But the tent kept the wind out, and sleeping packed together kept us all warm. The worst part was lying there with nothing to do but think about the emptiness of my stomach. I was starving, but I’d only been without real food for two days. The other people in the tent were much worse off. Nobody talked about it much, but I could see the hunger in their hollow cheeks, hear it in their moans and sighs.

I was finally starting to drift off when Darla kicked me. “Alex,” she whispered. “Get up.”

I rolled under the tent flap and jumped to my feet. Darla led me to the far side of the tent at a run. I saw three guys there, kids really; they were probably younger than I. One of them was pulling up the side of the tent, while another knelt and jammed his hands under the canvas. The third was standing guard.

I struck a pose, double outer knife-hand block. “Get out of our tent.” I tried to growl and sound like Clint Eastwood, but my voice cracked, and it came out more like Mike Tyson.

The guy standing guard punched one of the others on the shoulder. “Let’s get out of here.”

The other guy pulled his arms out of the tent and looked at me casually. “There ain’t nothing in this tent nohow.” He stood and the three of them backed away, watching me as they went.

“Thanks,” Darla said. “That’s the third time tonight. The other two were alone, so I chased them off.”

“Maybe I should take the first watch—it might quiet down later.”

“Yeah, let’s try that. Wake me up whenever you get tired. We can always nap during the day.”

I gave Darla a goodnight kiss, and she wormed under the tent flap to settle down where I’d been sleeping.

I slowly paced the circumference of the tent, trying to keep my strides even and counting one-Mississippi, two-Mississippi as I went. I thought a circuit of the tent was taking me about forty seconds. During my seventeenth trip, I saw a man and a woman walking up. I planted myself between them and the tent and glared until they moved on. During circuit fifty-eight, I found a guy already halfway under the side wall—only his butt and legs protruded. Someone inside woke up and yelled. I grabbed the guy’s ankles, yanked him backward out of the tent, and watched him run off into the night.

Things were quiet after that. When my count reached 360, I woke Darla. The blankets were warm and smelled faintly of her. I fell asleep instantly.