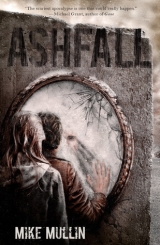

Текст книги "Ashfall"

Автор книги: Mike Mullin

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Chapter 9

I didn’t even make it out of the backyard.

As soon as I stood on the bike, both tires sank into the muddy ash. It was slick, and within a few feet I was stuck. The back wheel just spun and carved a trough. I stepped off the bike, wrenched it free, and tried again. Same result. It was hopeless. I could make better time hiking, not that hiking would get me to Warren this year.

I pulled the bike free again and wheeled it back into the garage. Even that short trip had left it coated in nasty white-gray goop.

I shrugged off my pack and sat on the garage floor to think. There had to be a better way to travel. I hadn’t seen any cars moving—they’d probably get stuck instantly. Plus, I wondered what the ash would do to a car’s engine. Nothing good. Walking was horrid because with every step my feet were swallowed by the stuff, and biking didn’t work because the wheels sank and couldn’t get traction due to the surprising slipperiness of the ash. It was sort of like a deep snowfall. Snowshoes might have worked if we’d had any. Maybe a couple of boards strapped to my feet? Or skis . . .?

When I was little, my dad had been an exercise nut. He’d run in the summer and ski cross-country when there was enough snow. Then he hurt his knee and got kind of pudgy. But his skis might still be in the garage somewhere.

I hunted for a couple of minutes and found them, stacked out of sight on a shelf above my head. I dragged everything down to the floor of the garage. Two skis, a pair of boots, two poles, and a pair of ski goggles. Everything was covered in dust, but that was okay. It’d get a lot dustier the moment I stepped outside.

I took off my boots, tied them to the outside of my pack, and slid into the ski boots. I put on the ski goggles and everything turned pink. Typical Dad: Even his ski goggles were rose-colored. At least they’d keep the ash out of my eyes.

I carried the skis and poles outside. The poles stood upright when planted in the muck at least as well as they would have in snow. The skis barely sank at all when I stood on them to snap the boots in place. That was encouraging—maybe this would work.

I’d only skied cross-country twice, on family vacations when Dad had rented skis for all of us. But I sort of remembered how. The skis didn’t glide over the wet ash the way they would have in snow, but the ash was slippery enough that I managed a decent pace by shuffling forward.

I headed northwest, toward my taekwondo dojang, Cedar Falls Taekwondo Academy. It was out of my way—I needed to go east to get to Warren. But I never brought my training weapons home; they stayed at the school. After what had happened at Darren’s house, I’d have felt a lot safer with something more than a short knife at my side. I planned to pick up my competition sword and ssahng jeol bongs (nunchucks, but I prefer the Korean words). Competition swords are dull but made of metal. Maybe I could sharpen mine somehow.

The roads were a chaos of crashed and abandoned cars. All of them had a foot or more of ash blanketing their roofs and hoods. In some places, so many cars were jammed across the road that I had trouble finding a path among them. Everyone must have gone crazy trying to escape Cedar Falls while I was holed up with Joe and Darren. It didn’t look like anyone had made it very far.

In other places, there were no cars at all. I didn’t see anything moving. Of course, I couldn’t see very far in the gloom and falling ash. The houses along the road were visible only briefly now and then during lightning flashes. Once, I thought I saw movement on a porch but couldn’t be sure.

The skiing was tough. I’d only gone a couple of blocks when my legs started to burn. Sliding the skis forward was easier than pulling my feet out of the goop, but it used a different set of muscles than walking or taekwondo.

My right shoulder wasn’t happy, either. It had gotten steadily better during the rest at Darren and Joe’s house, but the repetitive planting and pushing of my ski pole was aggravating the injury. I tried to do all my pushing with my left arm and rest the right, at least for now.

I paused, leaning against the trunk of a car that had wrapped its front end around a telephone pole. The car’s back windows were intact and opaque, caked with ash. I got a bottle of water out of the side pocket of my pack and sipped about half of it.

When I started out again, I saw the front of the car. The windshield and driver’s window had broken with the force of the crash. A guy (or girl, it was impossible to tell) sat in there, head leaning lifelessly against the steering wheel. Ash had blown into the car, mummifying him. I turned away quickly, feeling a little ill, even though really there was nothing particularly scary about the corpse. I couldn’t smell anything but sulfur or see any blood. Compared to the scene in Darren’s foyer, the car wreck was downright peaceful. But after that, I avoided looking into the wrecked cars.

When I reached the newer section of town, I found a particularly bad stretch of crashed cars. It forced me to take to the yards, skiing beside the houses. They were ranch-style homes here: one-story houses with low-sloping roofs. At least every other roof had collapsed. On one house, the collapsing roof had taken the walls with it. Nothing was left but part of the back wall and a lonely chimney.

I wasn’t making very good time. I used to ride my bike to taekwondo; it took less than fifteen minutes if I rode hard. I don’t know exactly how long it took me, skiing through the ash. Two hours, minimum. The slow pace was disheartening. At this rate, how long would it take me to get to Warren? Could I make it before my food ran out and I starved to death?

Across from the dojang was a restaurant I ate at sometimes, The Pita Pit. The skiing had left me hungry enough to eat two gyro specials and chase them with a two-liter Coke. I would have, too, if The Pita Pit had been more than a freestanding sign with a completely collapsed building behind it.

Amazingly, the strip mall that held the Cedar Falls Taekwondo Academy still stood. A pickup truck had rammed the front of the school, breaking most of the plate-glass windows. It had stopped with the cab inside the building and the bed on the sidewalk.

I unsnapped my boots from the skis. The mechanism had fouled with ash, and it took some work to scrape it clear. I walked through the window alongside the truck, carrying my skis in one hand and poles in the other. I tried to walk quietly, listening and looking around—it occurred to me that the occupants of the truck might still be there.

I didn’t see or hear anything. The truck was empty. I leaned my skis and poles against the front bumper and looked around.

The school was one big practice area with a padded floor plus an office and restrooms off to the side. I could see the front part of the school okay. The back and the office were shrouded in darkness.

I dug a candle out of my pack and lit it. Exploring by candlelight, I found that the place had been looted. The office was a shambles. Master Parker’s sword collection was gone. Someone had pulled the drawers out of the desks and file cabinets and dumped the contents, searching for God knows what. All the water bottles were missing from the mini-fridge.

I walked to the rear of the training room. That had been ransacked as well. Every one of the school’s edged weapons was gone, and the other stuff was scattered all over, as if someone had gone though it in a hurry, throwing aside everything they hadn’t wanted. I’d had a bag with my personal weapons on a rack at the back of the room. The rack was overturned, my bag gone.

I kicked the rack, feeling suddenly furious. What was it with Cedar Falls? People here had always been nice enough. But somehow the volcano had turned them into looters. Was everyone crazy now? We should have been sticking together and helping each other, not wrecking stuff.

I picked through the detritus on the practice floor. Most of it was junk that I hurled aside. Wooden practice swords. Soft foam bahng mahng ees, or short sticks. A set of padded ssahng jeol bongs, or nunchucks. Great to practice with, useless in a real fight. In the candlelight, I saw a dark gleam from the corner of the room and went to check it out. A long hardwood pole nestled against the edge of the mat. Master Parker’s personal jahng bong, or bö staff. I wondered if she’d mind if I borrowed it. Under normal circumstances, yes, she would mind. Under normal circumstances, I wouldn’t even ask.

It was a beautiful weapon. Six feet long, an inch and a quarter thick at the middle, and tapered to one inch at each end. Stained a deep chocolate color. The varnish was worn at the middle of the staff from hundreds, maybe thousands, of hours of practice. I carried it to the pickup truck where I’d left my skis and poles

I blew out the candle and sat on the front bumper to eat. I decided to have a can of pineapple for lunch on the theory that I’d get rid of some of the heavy stuff in my pack. I was still hungry when I finished but knew I needed to conserve food. I sucked down all the juice then tossed the empty can through the broken plate-glass window into the ash. With the ash and shards of plate glass everywhere, littering just didn’t seem to matter.

Three of my water bottles were empty now, so I relit the candle and went to check the restrooms. The toilet tank in the girls’ room was full. The water smelled fine and tasted okay, so I drank as much as I could and refilled my water bottles.

Judging time was tricky in the dim light. I thought about sacking out in the dojang. I was sore and hungry but not sleepy. I knocked as much of the ash off my makeshift bandanna as I could, wetted it down, and tied it around my face.

The bö staff was a problem. I couldn’t figure out any way to attach it to my pack, yet still keep it easy to grab in a hurry. Finally, I decided to leave one of my ski poles behind and use the staff instead. Planting the end into the ash over and over wasn’t going to do it any good, but I had little choice.

I pushed my skis east along First Street. Four blocks later, I turned south onto Division Street, which would take me past Cedar Falls High. I wanted to see if any of my friends were there. It didn’t seem likely—the building would probably be deserted. Surely school was canceled on account of the volcano.

Actually, the school was packed.

Chapter 10

As I approached my school, I saw a group of four people wearing backpacks, trudging toward the athletic entrance. I couldn’t tell who they were—they were covered in ash and had their backs to me—so I hung back and watched. They must have been dead tired; none of them so much as glanced around.

As I got closer to the building, I could make out a few figures on the roof. They were tossing shovelsful of ash over the edge.

The group ahead of me disappeared through the double doors that led to the school’s ticket office and basketball courts. I stopped, trying to decide whether to follow them or not.

I waited a few minutes. Nothing changed. The people on the roof were still shoveling ash. The fact that they were clearing the roof, trying to keep the ash from collapsing it, seemed like a good sign. Perhaps there were more people here working together to fight the ash. It was worth checking out. I skied to the doors, cracked one open, and peeked in.

The light in the short hallway was bright enough to hurt my eyes, which were adjusted to the dimness outside. A kerosene lantern hung from the ceiling. At the far edge of the light, somebody who looked a bit like Mr. Kloptsky, the principal, sat slumped in a folding chair. Next to him was a wiry old guy with a shotgun across his lap and a big guy I sort of recognized, although I couldn’t remember his name—a senior on the football team, I thought. He had an aluminum baseball bat between his knees. A couple of brooms leaned against the wall near the doors.

“Either move on or come in. You’re letting the ash in.” Definitely Mr. Kloptsky. I’d recognize that growl anywhere.

I closed the door, bent down, and popped the bindings on my skis. I reopened the door and stepped through, carrying my skis, pole, and staff awkwardly in both hands.

The guy with the shotgun walked up, eyeing me. He had the gun ready but pointed at the floor. “Bob’ll get some of that ash off ya. Stand still.”

The football player leaned his baseball bat against the wall and grabbed a broom. He proceeded to try to beat me senseless with it, scouring my clothing, backpack, and skis with the bristles. Wet ash fell off me in clumps.

When he finished, he started sweeping up the considerable pile of ash he’d knocked off me. The guy with the shotgun said, “Go on, Kloptsky’ll talk to ya now.”

I walked down the short hall to where Mr. Kloptsky sat hunched in his chair. He gestured at the empty metal folding chair beside him, and I sat down.

“You look familiar,” he said.

“Yeah. I go to school here. Went, I guess. I’m Alex Halprin.”

“Freshman last year. Mrs. Sutton’s homeroom, right?”

“Yeah.” Damn, I was impressed. Eleven hundred students, and he remembered one quiet freshman?

“Where are your folks?”

“Warren, Illinois, I hope.”

“You can stay here. You’ll have to work, though. Every able-bodied person is doing something. I’ll assign you to a team in the morning. Food scavenging, roof clearing, or security, maybe.”

Oh, I was tempted. Finally I’d found some people organizing, working to overcome the ash instead of just looting. Maybe I’d be safe here. But last night I’d made a promise to myself: I was going to find my family. “Actually, I was only looking for a place to sleep. I’ll move on in the morning—I’m headed for Warren.”

“Better you wait for help. We don’t have any communication across Cedar Falls or Waterloo yet. Who knows what’s going on farther east.”

“I need to find my family.”

“Suit yourself. Lord knows I’ve already got more mouths than I can feed here.” His voice dropped to a whisper. “You have any food with you?”

“Yeah. You want some?”

“If you’re trying to get to Illinois, you’ll need it,” he said, still whispering. “I’d advise you not to let on that you’ve got food. We ran out yesterday. We don’t keep much in the cafeteria on weekends. We’re scavenging what we can, but it’s not enough. School has its own water tank, thank God. And there are plenty of cots and blankets—we’re a Red Cross disaster site. But they planned on trucking in food during an emergency.”

“Um, thanks.”

“Cots are set up in the gym. Take any empty spot you like.”

“Thanks.”

I carried my junk into the gym. It was packed with row upon row of folding cots arrayed with the head of each almost touching the foot of the next. Narrow aisles separated each row. Maybe two-thirds of the cots were occupied. There were hundreds of people in there, not all of them students. Another kerosene lantern hung from one of the basketball goals, throwing long shadows toward the corners of the gym.

There was a cluster of empty cots in one of the dark areas along a wall. I picked a cot at random and shoved my skis, ski pole, and staff underneath. I was ravenous but didn’t want anyone to see me eating, so I settled for drinking a bottle of water. Toilet water from the girls’ restroom at the dojang, but who could be picky now?

I put the empty water bottle away, shoved my pack under the cot, and stripped down to my T-shirt and boxers. It felt great to get out of my filthy clothing and crawl into a bed.

My arms and legs ached. I’d only been skiing for a day, hadn’t even left Cedar Falls yet, but I was exhausted. Could I make it all the way to Warren? Despite that worry, I felt hopeful. If people were organizing to survive the ashfall here, maybe they’d be organizing in Warren, too. Maybe my family would be okay.

The cot was small, with a tiny pillow and scratchy blanket. People were moving around, messing with their gear or talking to their neighbors. A bunch of them were coughing, great hacking fits brought on by the ash. A mother tried to shush a crying baby, and across the gym two kids argued. I was so tired that none of it mattered. I fell asleep inside five minutes.

Baseball Bat, Tire Iron, and Chain returned to my dreams. Baseball Bat wound up and swung at my head. I couldn’t move, couldn’t scream. As he was about to connect, his head exploded. When he fell, he opened up a whole new vista behind him, in that weird way dreams sometimes work. Mom, Dad, and Rebecca were there, eating Chicken McNuggets. I was in a clown costume, but they didn’t recognize me. Every time I told them who I was, they laughed.

I woke up, panting quietly and staring into the darkness overhead. Someone had turned the lantern way down. I felt something bump my back through the canvas cot. I turned my head and saw a dim form kneeling beside me, reaching under my cot with one arm. I snaked my arms out from under the blanket and grabbed for it. I got a fistful of hair with my right hand and yanked it backward and up. That told me about where the guy’s throat should be, so I went for a chokehold with my left forearm.

The whole thing was over in less than two seconds. I craned my head to get a look at the side of his face.

Her face. It was a girl, maybe eight or nine years old. I let go of her hair—my right shoulder ached, anyway. I kept my left forearm locked around her neck. She had pulled two packages of peanut-butter crackers out of my pack. They slipped out of her hands and fell to the floor.

What was wrong with me? I’d been shocked to see Cedar Falls degenerate into looting and violence, but here I was with my forearm crushing a little girl’s throat, a little girl who only wanted something to eat. Was I any better than the looters?

I reached down and felt around the floor. I found both packages of crackers by touch. I scooped them up, put them back in her hand, and curled her fingers around them.

“If you tell anyone where you got these, I’ll find you and break your neck.” I tugged my forearm a little tighter against her throat to emphasize the point. I felt horrible. It was wrong, nasty even, to threaten her. But I couldn’t think of any alternative. I didn’t want everyone to help themselves to my food. She nodded, at least as much as she could with my arm crushed against her larynx.

I let her go, and she shot off into the gloom, both hands clutched around the crackers. The top of my pack was open under the cot, stuff falling out. I put it back together and set it on the cot next to me.

I lay awake for several hours with one arm thrown over my pack, hugging it and thinking. Would anyone survive if food was already so scarce that kids were going hungry? Then I thought about what might have happened if I’d tightened my arm a bit more around her throat, and I felt sick. Mostly, I thought about a little girl who had learned to steal just to get something to eat.

Chapter 11

When I awoke the next morning, about half the refugees in the gym were already up. They tried to move quietly and talked in whispers out of consideration for the sleepers. But more than a hundred people trying to be quiet made a heck of a lot of noise.

I sat up on the edge of the cot and groaned when my feet touched the floor. All that skiing yesterday had done nothing good for the muscles in my calves and thighs. So I staggered off the cot and forced myself through some martial arts stretches in my boxers. After I’d gotten my legs loosened up, I spent some time stretching my right arm and shoulder. It was feeling a lot better, although it still hurt to push my arm above my head.

By the time I finished stretching, I felt okay, so I started doing telephone-booth forms. An ordinary form is a series of kicks, punches, and stances that requires a pretty big space to perform. So to practice in a smaller area, I had to modify the moves. If the form called for a step forward, front kick, step forward, knife-hand strike, I’d step backward for the second move instead, covering and recovering the same small patch of ground.

People nearby were looking at me funny, so I called it quits after two forms and pulled on the same dirty jeans and long-sleeved shirt I’d been wearing yesterday. I put on my dad’s hiking boots and threw my backpack over my shoulder, but I wasn’t sure what to do with the skiing gear. I waited until nobody seemed to be paying attention and hid the stuff under the blanket on my cot. Hopefully it’d be okay.

The next order of business: a toilet. I knew where the closest boys’ restroom was, but when I got there, partway down a pitch-black hallway, it was locked. I returned to the gym and asked the first guy I saw where we were supposed to pee. He pointed me toward the home locker room.

There was another camp lantern hanging in the locker room, turned about as low as possible while still giving off light. The urinals and stalls were blocked with yellow out-of-order tape. Somebody had dragged two Porta-Potties into the shower room, right in the middle near the floor drain. There were two lines, each four or five people deep, both men and women waiting for the facilities.

I got in line to wait my turn behind a young girl. I wondered if she was the same one who’d raided my pack last night. If she was, should I apologize or scold her for trying to steal from me? There were no marks on her neck, so I decided she must not have been the same girl.

The Porta-Potty reeked: a truly foul mix of feces, urine, and sulfur. I assumed they’d run out of that blue stuff they put at the bottom to keep it smelling decent. I took one breath while I was inside. I’d have skipped even that, but the idea of passing out in the Porta-Potty was even more disgusting than the smell.

While standing in the Porta-Potty, food was the last thing on my mind. But the moment I got out of the locker room, my hunger returned, gnawing at my gut. So I made my way down one of the dark hallways leading away from the gym. I navigated by feel, running my hand along the banks of lockers.

About halfway down the hall, I stopped at a door, which, if memory served, should have led to a classroom. The door was unlocked, so I opened it and stepped carefully inside. It was as dark in there as it had been in the hall. I sidestepped a couple feet, slid off my pack, and sat with my back to the wall.

I groped around in my pack and found a brick of cheese and two water bottles. I ate all the cheese and drank both bottles of water. What kind of guy eats his private stash of food when he knows there are hundreds of hungry people nearby? A guy like me, I guessed. Yeah, I felt bad about it. But I didn’t think my meager stash would have made much of a difference to all the people in that gym. And I knew I’d need the food to get to Warren. I’d probably need more than I had. I reloaded my pack and ran my hands over the floor to make sure nothing had fallen out.

Back in the gym I asked a kid where to get water. He pointed me toward the visitors’ locker room. There was another lantern hanging in there and two guys sitting on folding chairs. I asked them about water, and they led me to the showers. One of the showerheads had been replaced with a hose. I gave them my empty water bottles, and they refilled all of them from the hose, working carefully, spilling nothing.

I was a little surprised to see that the plumbing worked. But I figured it was like Mr. Kloptsky had told me yesterday—the school had its own water tank. It must have been high enough to feed the locker room by gravity. I hoped they had enough water to last until they got some help.

When I got back to the gymnasium, the lantern had been fully turned up and almost everyone was awake. I checked my skiing gear—it was still safely tucked under the blanket on my cot. I wandered around the gym for a bit, looking for anyone I knew.

I found Spork. Ian, really, but we called him Spork in honor of the utensil his dad had packed with his lunches in junior high. His mom was in the military. It seemed like every other year she was off in some Middle Eastern country. Afghanistan right now, I thought.

“Yo, Spork,” I called.

“Yo, Mighty Mite,” he replied, walking over to me. I hated that nickname. I mean, come on, I’m not that small. Sort of average-sized. Although I guess Mighty Mite beat Spork.

“So, is this messed up or what?”

“No, this is FUBAR. In the classic military definition. Effed up beyond—”

“Yeah, I know—all recognition.”

“Recall, or remote possibility of rescue. So what you doing here? I think I’m on roof clearing duty today—want to see if we can get assigned to work together, man?”

“Roof clearing?”

“Yeah, Kloptsky thinks the roof’ll collapse if we don’t shovel it off.”

“Huh. Bet he’s right. The Pita Pit’s flattened. Lots of houses on the way here were, too.”

A girl I knew walked up while I was talking. Laura. A lot of kids called her Ingalls because of her name and the old-fashioned long skirts she always wore. I didn’t because, well, she was cute. Even here she wore a long denim skirt streaked with ash.

“Yo, Ingalls,” Spork said. “What duty did you pull? I’m on roof clearing.”

She scowled at Spork and glanced my way. “Hey, Alex. Good to see you made it here okay.”

“Yeah,” I replied. “Good to see you’re okay, too. You stuck shoveling roofs or something?”

“No, I’m getting out of here. My whole church is leaving today. You want to come?”

“Sure.” I figured I’d see which way they were going. Maybe they’d head east, and I could tag along and get closer to Warren.

“So what’re you doing, Ingalls? Driving the church bus out of here?” Spork smirked at her. We both knew there was no way anything short of a bulldozer could drive through all the wet, slippery ash. I was also a little puzzled about how her church planned to leave.

“No,” she said. “Come on, Alex.”

“I gotta get my stuff. I’ll meet you at the door, okay?” I trotted to my cot and grabbed my gear. I put on the ski boots, tied the hiking boots to my pack, and carried everything else.

Laura and Spork were standing just inside the doors. They’d already wrapped their faces in damp rags. I dribbled a little water on one of my torn-up T-shirts and wrapped it around my mouth and nose.

“Thought you were shoveling off the roof,” I said to Spork.

“So I’ll be late. Won’t be the first time Kloptsky has yelled at me. And I want to see how you guys are getting out of here.”

I shrugged. “Okay.”

It was a little brighter that morning. The ash was still falling, but I could see farther today. The rain had quit, but the ash was wet and slushy from yesterday. Oddly enough, the lightning and thunder continued unabated, even without any rain.

I slowed my skiing to a crawl so as not to outpace Laura and Spork. While they struggled with every step, wrenching their feet free of the muck and plodding forward, I skimmed the surface. It wasn’t easy, though. My muscles protested, particularly after all the abuse they’d endured over the last few days. But watching Laura and Spork made me aware of how much the skis were helping.

Laura’s church was only fifteen or sixteen blocks from the high school, but it took what seemed like hours to get there. The church was a yellow brick building dominated by a big square bell tower at the front. Metal letters bolted onto the brick beside the entrance proclaimed REDEEMER BAPTIST. Ash had collected in tall peaks atop the letters, giving them a Gothic look. I thought I saw some movement in the bell tower above us.

It was impossible to tell where the church’s lawn, parking lot, and driveway began or ended. It was all one ashy plain. A couple of scraggly trees were bent under the weight of the ash, coated so thoroughly that not a speck of green was visible. Four cars and the church bus were parked to the side where the parking lot must have been. All of them were buried under more than a foot of ash.

Laura led us to the side door of the church, protected by a steep-roofed porte-cochère. I unclipped my boots from my skis and leaned the skis against the wall inside the doors. Spork was trying to bang the dust off his clothing and boots, but Laura told him to forget about it, since everyone would be leaving the building soon, anyway.

Someone had left a single candle burning in the sanctuary. By its light, I could see the church was modern, with a bright red carpet and oak pews. There was a path of near-white ash tracked on the carpet, which we followed to the back of the sanctuary and up a staircase to the small balcony.

Another, steeper staircase led upward from the balcony. It turned on itself in a square pattern, following the walls of the bell tower. I was surprised not to see any ropes dangling in the middle to ring the bells. Maybe they did that electronically or omitted the bells altogether. There were windows set into the walls, but the day outside was so dim that not much light leaked into the tower. I held the handrail and took the stairs slowly. It would be a long fall if I tripped in the darkness.

We went up five or six flights and stopped at a hatch set into the ceiling. Laura pushed the hatch open, and the three of us emerged onto an open area under the roof of the bell tower.

It was maybe sixteen feet on a side, but it felt small and crowded. At least twenty people were jammed together up there. All four walls of the bell tower were open to the elements; we were protected from a long fall by only a low brick railing. Ash swirled over the railings, forming drifts inside.

A guy in a minister’s robe was preaching; everyone else faced him, listening. Laura slid through the crowd to someone I took to be her mom.

“Yo, Mrs. Wilder,” Spork said.

“Our last name is Johnston, you idiot,” Laura whispered.

“Be quiet and listen to Reverend Rowan,” Mrs. Johnston whispered sternly.

So I did. He had a powerful head of preaching going: gesturing and sweating and shouting. He was saying something about a fourth seal when I started paying attention. “Behold! A pale horse. Pale because he’s coated in this ash, my brothers and sisters. And his name that sat upon the horse was Death, and Hell followed with him. This,” the reverend made a sweeping gesture, “is a foretaste of Hell; this is the ash that precedes the flood of fire and brimstone. A fourth of the earth shall be given over to famine and pestilence. This fourth, our fourth, where we lived. For this ash is the pestilence that will bring famine. If you are not summoned, if Jesus does not call you to His home, you will surely die. Our Lord told us this was coming. In the book of Matthew, He said, ‘The sun shall be darkened and the moon will not give its light. Therefore you must also be ready; for the Son of man is coming at an hour you do not expect.’ Pray with me now, pray with me, brothers and sisters, for Jesus to carry us up to sit at His right hand.”