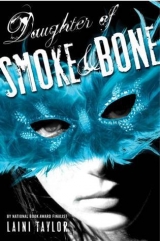

Текст книги "Daughter of Smoke & Bone"

Автор книги: Лэйни Тейлор

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

“Chemical. Now that’s romantic.”

“I know, right? Stupid butterflies.” Liking the idea, Karou opened her sketchbook and started to draw it: cartoon intestines and a stomach crowded with butterflies. Papilio stomachus would be their Latin name.

Zuzana asked, “So, if it’s all chemical and you have no say in the matter, does that mean Jackass still makes your butterflies dance?”

Karou looked up. “God no. I think he makes my butterflies barf.”

Zuzana had just taken a sip of tea and her hand flew to her mouth in an effort to keep it in. She laughed, doubled over, until she managed to swallow. “Oh, gross. Your stomach is full of butterfly barf!”

Karou laughed, too, and kept sketching. “Actually, I think my stomach is full of dead butterflies. Kaz killed them.”

She wrote, Papilio stomachus: fragile creatures, vulnerable to frost and betrayal.

“So what,” said Zuzana. “They had to be pretty stupid butterflies to fall for him anyway. You’ll grow new ones with more sense. New wise butterflies.”

Karou loved Zuzana for her willingness to play out such silliness on a long kite string. “Right.” She raised her teacup in a toast. “To a new generation of butterflies, hopefully less stupid than the last.” Maybe they were burgeoning even now in fat little cocoons. Or maybe not. It was hard to imagine feeling that magical tingling sensation in the pit of her belly anytime soon. Best not to worry about it, she thought. She didn’t need it. Well. She didn’t want to need it. Yearning for love made her feel like a cat that was always twining around ankles, meowing Pet me, pet me, look at me, love me.

Better to be the cat gazing coolly down from a high wall, its expression inscrutable. The cat that shunned petting, that needed no one. Why couldn’t she be that cat?

Be that cat!!! she wrote, drawing it into the corner of her page, cool and aloof.

Karou wished she could be the kind of girl who was complete unto herself, comfortable in solitude, serene. But she wasn’t. She was lonely, and she feared the missingness within her as if it might expand and… cancel her. She craved a presence beside her, solid. Fingertips light at the nape of her neck and a voice meeting hers in the dark. Someone who would wait with an umbrella to walk her home in the rain, and smile like sunshine when he saw her coming. Who would dance with her on her balcony, keep his promises and know her secrets, and make a tiny world wherever he was, with just her and his arms and his whisper and her trust.

The door opened. She looked in the mirror and suppressed a curse. Slipping in behind some tourists, that winged shadow was back again. Karou rose and made for the bathroom, where she took the note that Kishmish had come to deliver.

Again it bore a single word. But this time the word was Please.

11

11

P LEASE

Please? Brimstone never said please. Hurrying across town, Karou found herself more troubled than if the note had said something menacing, like: Now, or else.

Letting her in, Issa was uncharacteristically silent.

“What is it, Issa? Am I in trouble?”

“Hush. Just come in and try not to berate him today.”

“Berate him?” Karou blinked. She’d have thought if anyone was in danger of being berated, it was herself.

“You’re very hard on him sometimes, as if it’s not hard enough already.”

“As if what’s not hard enough?”

“His life. His work. His life is work. It’s joyless, it’s relentless, and sometimes you make it harder than it already is.”

“Me?” Karou was stunned. “Did I just come in on the middle of a conversation, Issa? I have no idea what you’re talking about—”

“Hush, I said. I’m just asking that you try to be kind, like when you were little. You were such a joy to us all, Karou. I know it’s not easy for you, living this life, but try to remember, always try to remember, you’re not the only one with troubles.”

And with that the inner door unsealed and Karou stepped across the threshold. She was confused, ready to defend herself, but when she saw Brimstone, she forgot all that.

He was leaning heavily on his desk, his great head resting in one hand, while the other cupped the wishbone he wore around his neck. Kishmish hopped in agitation from one of his master’s horns to the other, uttering crickety chirrups of concern, and Karou faltered to a halt. “Are… are you okay?” It felt odd asking, and she realized that of all the questions she had barraged him with in her life, she had never asked him that. She’d never had reason to—he’d scarcely ever shown a hint of emotion, let alone weakness or weariness.

He raised his head, released the wishbone, and said simply, “You came.” He sounded surprised and, Karou thought guiltily, relieved.

Striving for lightness, she said, “Well, please is the magic word, you know.”

“I thought perhaps we had lost you.”

“Lost me? You mean you thought I’d died?”

“No, Karou. I thought that you had taken your freedom.”

“My…” She trailed off. Taken her freedom? “What does that even mean?”

“I’ve always imagined that one day the path of your life would unroll at your feet and carry you away from us. As it should, as it must. But I am glad that day is not today.”

Karou stood staring at him. “Seriously? I blow off one errand and you think that’s it, I’m gone forever? Jesus. What do you think of me, that you think I’d just vanish like that?”

“Letting you go, Karou, will be like opening the window for a butterfly. One does not hope for the butterfly’s return.”

“I’m not a freaking butterfly.”

“No. You’re human. Your place is in the human world. Your childhood is nearly over—”

“So… what? You don’t need me anymore?”

“On the contrary. I need you now more than ever. As I said, I’m glad that today is not the day you leave us.”

This was all news to Karou, that there would come a day when she would leave her chimaera family, that she even possessed the freedom to do so if she wished. She didn’t wish. Well, maybe she wished not to go on some of the creepier errands, but that didn’t mean she was a butterfly fluttering against glass, trying to get out and away. She didn’t even know what to say.

Brimstone pushed a wallet across the desk to her.

The errand. She’d almost forgotten why she was here. Angry, she grabbed the wallet and flipped it open. Dirhams. Morocco, then. Her brow furrowed. “Izîl?” she asked, and Brimstone nodded.

“But it’s not time.” Karou had a standing appointment with a graverobber in Marrakesh the last Sunday of every month, and this was Friday, and a week early.

“It is time,” said Brimstone. He gestured to a tall apothecary jar on the shelf behind him. Karou knew it well; usually it was full of human teeth. Now it stood nearly empty.

“Oh.” Her gaze roved along the shelf, and she saw, to her surprise, that many of the jars were likewise dwindling. She couldn’t remember a time when the tooth supply had been so low. “Wow. You’re really burning through teeth. Something going on?”

It was an inane question. As if she could understand what it meant that he was using more teeth, when she didn’t know what they were for to begin with.

“See what Izîl has,” Brimstone said. “I’d rather not send you anywhere else for human teeth, if it can be helped.”

“Yeah, me, too.” Karou ran her fingers lightly over the bullet scars on her belly, remembering St. Petersburg, the errand gone horribly wrong. Human teeth, despite being in such abundant supply in the world, could be… interesting… to procure.

She would never forget the sight of those girls, still alive in the cargo hold, mouths bloody, other fates awaiting them next.

They may have gotten away. When Karou thought of them now, she always added a made-up ending, the way Issa had taught her to do with nightmares so she could fall back to sleep. She could only bear the memory if she believed she’d given those girls time to escape their traffickers, and maybe she even had. She’d tried.

How strange it had been, being shot. How unalarmed she’d found herself, how quick to unsheathe her hidden knife and use it.

And use it. And use it.

She had trained in fighting for years, but she had never before had to defend her life. In the flash of a moment, she had discovered that she knew just what to do.

“Try the Jemaa el-Fna,” Brimstone said. “Kishmish spotted Izîl there, but that was hours ago, when I first summoned you. If you’re lucky, he might still be there.” And with that, he bent back over his tray of monkey teeth, and Karou was apparently dismissed. Now there was the old Brimstone, and she was glad. This new creature who said “please” and talked about her like she was a butterfly—he was unsettling.

“I’ll find him,” Karou said. “And I’ll be back soon, with my pockets full of human teeth. Ha. I bet that sentence hasn’t been said anywhere else in the world today.”

The Wishmonger didn’t respond, and Karou hesitated in the vestibule. “Brimstone,” she said, looking back, “I want you to know I would never just… leave you.”

When he raised his reptilian eyes, they were bleary with exhaustion. “You can’t know what you will do,” he said, and his hand went again to his wishbone. “I won’t hold you to that.”

Issa closed the door, and even after Karou stepped out into Morocco, she couldn’t shake the image of him like that, and the uneasy feeling that something was terribly wrong.

12

12

S OMETHING E LSE E NTIRELY

Akiva saw her come out. He was approaching the doorway, was just steps from it when it swung open, letting loose an acrid flood of magic that set his teeth on edge. Through the portal stepped a girl with hair the improbable color of lapis lazuli. She didn’t see him, seeming lost in thought as she hurried past.

He said nothing but stood looking after her as she moved away, the curve of the alley soon robbing him of the sight of her and her swaying blue hair. He shook himself, turned back to the portal, and laid his hand on it. The hiss of the scorch, his hand limned in smoke, and it was done: the last of the doorways that were his to mark. In other quarters of the world, Hazael and Liraz would be finishing, too, and winging their way toward Samarkand.

Akiva was poised to spring skyward and begin the last leg of his journey, to meet them there before returning home, but a heartbeat passed, then another, and still he stood with his feet on the earth, looking in the direction the girl had gone.

Without quite deciding to do it, he found himself following her.

How, he wondered, when he caught the lamp-lit shimmer of her hair up ahead, had a girl like that gotten mixed up with the chimaera? From what he’d seen of Brimstone’s other traders, they were rank brutes with dead eyes, stinking of the slaughterhouse. But her? She was a shining beauty, lithe and vivid, though surely this wasn’t what intrigued him. All of his own kind were beautiful, to such an extent that beauty was next to meaningless among them. What, then, compelled him to follow her, when he should have taken at once to the sky, the mission so near completion? He couldn’t have said. It was almost as if a whisper beckoned him onward.

The medina of Marrakesh was labyrinthine, some three thousand blind alleys intertwined like a drawer full of snakes, but the girl seemed to know her route cold. She paused once to run a finger over the weave of a textile, and Akiva slowed his steps, veering off to one side so he could see her better.

There was a look of unguarded wistfulness on her pale, pretty face—a kind of lostness—but the moment the vendor spoke to her, it transmuted to a smile like light. She answered easily, making the man laugh, and they bantered back and forth, her Arabic rich and throaty, with an edge like a purr.

Akiva watched her with hawklike fixedness. Until a few days ago, humans had been little more than legend to him, and now here he was in their world. It was like stepping into the pages of a book—a book alive with color and fragrance, filth and chaos—and the blue-haired girl moved through it all like a fairy through a story, the light treating her differently than it did others, the air seeming to gather around her like held breath. As if this whole place were a story about her.

Who was she?

He didn’t know, but some intuition sang in him that, whoever she was, she was not just another of Brimstone’s street-level grim reapers. She was, he was sure, something else entirely.

His gaze unwavering, he prowled after her as she made her way through the medina.

13

13

T HE G RAVEROBBER

Karou walked with her hands in her pockets, trying to shake her uneasiness about Brimstone. That stuff about “taking her freedom”—what was that about? It gave her a creeping sense of impending aloneness, like she was some orphaned animal raised by do-gooders, soon to be released into the wild.

She didn’t want to be released into the wild. She wanted to be held dear. To belong to a place and a family, irrevocably.

“Magic healings here, Miss Lady, for the melancholy bowels,” someone called out to her, and she couldn’t help smiling as she shook her head in demurral. How about melancholy hearts? she thought. Was there a cure for that? Probably. There was real magic here among the quacks and touts. She knew of a scribe dressed all in white who penned letters to the dead (and delivered them), and an old storyteller who sold ideas to writers at the price of a year of their lives. Karou had seen tourists laugh as they signed his contract, not believing it for a second, but she believed it. Hadn’t she seen stranger things?

As she made her way, the city began to distract her from her mood. It was hard to be glum in such a place. In some derbs, as the wending alleyways were called, the world seemed draped in carpets. In others, freshly dyed silks dripped scarlet and cobalt on the heads of passersby. Languages crowded the air like exotic birds: Arabic, French, the tribal tongues. Women chivvied children home to bed, and old men in tarboosh caps leaned together in doorways, smoking.

A trill of laughter, the scent of cinnamon and donkeys, and color, everywhere color.

Karou made her way toward the Jemaa el-Fna, the square that was the city’s nerve center, a mad, teeming carnival of humanity: snake charmers and dancers, dusty barefoot boys, pickpockets, hapless tourists, and food stalls selling everything from orange juice to roasted sheep’s heads. On some errands, Karou couldn’t get back to the portal fast enough, but in Marrakesh she liked to linger and wander, sip mint tea, sketch, browse through the souks for pointy slippers and silver bracelets.

She would not be lingering tonight, however. Brimstone was clearly anxious to have his teeth. She thought again of the empty jars, and furious curiosity strummed at her mind. What was it all about? What? She tried to stop wondering. She was going to find the graverobber, after all, and Izîl was nothing if not a cautionary tale.

“Don’t be curious” was one of Brimstone’s prime rules, and Izîl had not obeyed it. Karou pitied him, because she understood him. In her, too, curiosity was a perverse fire, stoked by any effort to extinguish it. The more Brimstone ignored her questions, the more she yearned to know. And she had a lot of questions.

The teeth, of course: What the hell were they all for?

What of the other door? Where did it lead?

What exactly were the chimaera, and where had they come from? Were there more of them?

And what about her? Who were her parents, and how had she fallen into Brimstone’s care? Was she a fairy-tale cliché, like the firstborn child in “Rumpelstiltskin,” the settlement of some debt? Or perhaps her mother had been a trader strangled by her serpent collar, leaving a baby squalling on the floor of the shop. Karou had thought of a hundred scenarios, but the truth remained a mystery.

Was there another life she was meant to be living? At times she felt a keen certainty that there was—a phantom life, taunting her from just out of reach. A sense would come over her while she was drawing or walking, and once when she was dancing slow and close with Kaz, that she was supposed to be doing something else with her hands, with her legs, with her body. Something else. Something else. Something else.

But what?

She reached the square and wandered through the chaos, her movements synchronizing themselves to the rhythms of mystical Gnawa music as she dodged motorbikes and acrobats. Billows of grilled-meat smoke gusted thick as houses on fire, teenage boys whispered “hashish,” and costumed water-sellers clamored “Photo! Photo!” At a distance, she spotted the hunchback shape of Izîl among the henna artists and street dentists.

Seeing him at one-month intervals was like watching a time-lapse of decline. When Karou was a child, he was a doctor and a scholar—a straight and genteel man with mild brown eyes and a silky mustache he preened like plumage. He had come to the shop himself and done business at Brimstone’s desk, and, unlike the other traders, he always made it seem like a social call. He flirted with Issa, brought her little gifts—snakes carved from seedpods, jade-drop earrings, almonds. He brought dolls for Karou, and a tiny silver tea service for them, and he didn’t neglect Brimstone, either, casually leaving chocolates or jars of honey on the desk when he left.

But that was before he’d been warped by the weight of a terrible choice he’d made, bent and twisted and driven mad. He wasn’t welcome in the shop anymore, so Karou came out to meet him here.

Seeing him now, tender pity overcame her. He was bent nearly double, his gnarled olivewood walking stick all that kept him from collapsing on his face. His eyes were sunk in bruises, and his teeth, which were not his own, were overlarge in his shrunken face. The mustache that had been his pride hung lank and tangled. Any passerby would be taken with pity, but to Karou, who knew how he had looked only a few years earlier, he was a tragedy to behold.

His face lit up when he saw her. “Look who it is! The Wishmonger’s beautiful daughter, sweet ambassadress of teeth. Have you come to buy a sad old man a cup of tea?”

“Hello, Izîl. A cup of tea sounds perfect,” she said, and led him to the cafe where they usually met.

“My dear, has the month passed me by? I’m afraid I’d quite forgotten our appointment.”

“Oh, you haven’t. I’ve come early.”

“Ah, well, it’s always a pleasure to see you, but I haven’t got much for the old devil, I’m afraid.”

“But you have some?”

“Some.”

Unlike most of the other traders, Izîl neither hunted nor murdered; he didn’t kill at all. Before, as a doctor working in conflict zones, he’d had access to war dead whose teeth wouldn’t be missed. Now that madness had lost him his livelihood, he had to dig up graves.

Quite abruptly, he snapped, “Hush, thing! Behave, and then we’ll see.”

Karou knew he was not speaking to her, and politely pretended not to have heard.

They reached the cafe. When Izîl dropped into his chair, it strained and groaned, its legs bowing as if beneath a weight far greater than this one wasted man. “So,” he asked, settling in, “how are my old friends? Issa?”

“She’s well.”

“I do so miss her face. Do you have any new drawings of her?”

Karou did, and she showed them to him.

“Beautiful.” He traced Issa’s cheek with his fingertip. “So beautiful. The subject and the work. You are very talented, my dear.” Seeing the episode with the Somali poacher, he snorted, “Fools. What Brimstone has to endure, dealing with humans.”

Karou’s eyebrows went up. “Come on, their problem isn’t that they’re human. It’s that they’re subhuman.”

“True enough. Every race has its bad seeds, one supposes. Isn’t that right, beast of mine?” This last bit he said over his shoulder, and this time a soft response seemed to emanate from the air.

Karou couldn’t help herself. She glanced at the ground, where Izîl’s shadow was cast crisp across the tiles. It seemed impolite to peek, as if Izîl’s… condition… ought to be ignored, like a lazy eye or birthmark. His shadow revealed what looking at him directly did not.

Shadows told the truth, and Izîl’s told that a creature clung to his back, invisible to the eye. It was a hulking, barrel-chested thing, its arms clenched tight around his neck. This was what curiosity had gotten him: The thing was riding him like a mule. Karou didn’t understand how it had come about; she only knew that Izîl had made a wish for knowledge, and this had been the form of its fulfillment. Brimstone warned her that powerful wishes could go powerfully awry, and here was the evidence.

She supposed that the invisible thing, who was called Razgut, had held the secrets Izîl had hungered to know. Whatever they were, surely this price was far too high.

Razgut was talking. Karou could make out only the faintest whisper, and a sound like a soft smack of fleshy lips.

“No,” Izîl said. “I will not ask her that. She’ll only say no.”

Karou watched, repelled, as Izîl argued with the thing, which she could see only in shadow. Finally the graverobber said, “All right, all right, hush! I’ll ask.” Then he turned to Karou and said, apologetically, “He just wants a taste. Just a tiny taste.”

“A taste?” She blinked. Their tea had not yet arrived. “Of what?”

“Of you, wish-daughter. Just a lick. He promises not to bite.”

Karou’s stomach turned. “Uh, no.”

“I told you,” Izîl muttered. “Now will you be quiet, please?”

A low hiss came in response.

A waiter in a white djellaba came and poured mint tea, raising the pot to head height and expertly aiming the long stream of tea into etched glasses. Karou, eyeing the hollows of the graverobber’s cheeks, ordered pastries, too, and she let him eat and drink for a while before asking, “So, what have you got?”

He dug into his pockets and produced a fistful of teeth, which he dropped on the table.

Watching from the shadow of a nearby doorway, Akiva straightened up. All went still and silent around him, and he saw nothing but those teeth, and the girl sorting through them in just the way he knew the old beast sorcerer did.

Teeth. How harmless they looked on that tabletop—just tiny, dirty things, plundered from the dead. And if they stayed in this world where they belonged, that was all they’d ever be. In Brimstone’s hands, though, they became so much more than that.

It was Akiva’s mission to end this foul trade, and with it, the devil’s dark magic.

He watched as the girl inspected the teeth with what was clearly a practiced hand, as if she did this all the time. Mixed with his disgust was something like disappointment. She had seemed too clean for this business, but apparently she was not. He’d been right, though, in his guess that she was no mere trader. She was more than that, sitting there doing Brimstone’s work. But what?

“God, Izîl,” said Karou. “These are nasty. Did you bring them straight from the cemetery?”

“Mass grave. It was hidden, but Razgut sniffed it out. He can always find the dead.”

“What a talent.” Karou got a chill, imagining Razgut leering at her, hoping for a taste. She turned her attention to the teeth. Scraps of dried flesh clung to their roots, along with the dirt they’d been exhumed from. Even through the filth, it was easy to see that they were not of high quality, but were the teeth of a people who had gnawed at tough food, smoked pipes, and been unacquainted with toothpaste.

She scooped them off the table and dropped them into the dregs of her tea, swishing it around before dumping it out in a sodden pile of mint leaves and teeth, now only slightly less filthy. One by one, she picked them up. Incisors, molars, canines, adult and child alike. “Izîl. You know Brimstone doesn’t take baby teeth.”

“You don’t know everything, girl,” he snapped.

“Excuse me?”

“Sometimes he does. Once. Once he wanted some.”

Karou didn’t believe him. Brimstone strictly did not buy immature teeth, not animal, not human, but she saw no point in arguing. “Well”—she pushed the tiny teeth aside and tried not to think about small corpses in mass graves—“he didn’t ask for any, so I’ll have to pass.”

She held each of the adult teeth, listening to what their hum told her, and sorted them into two piles.

Izîl watched anxiously, his gaze darting from one pile to the other. “They chewed too much, didn’t they? Greedy gypsies! They kept chewing after they were dead. No manners. No table manners at all.”

Most of the teeth were worn blunt, riddled with decay, and no good to Brimstone. By the time Karou was through sorting, one pile was larger than the other, but Izîl didn’t know which was which. He pointed hopefully to the larger pile.

She shook her head and fished some dirham notes out of the wallet Brimstone had given her. It was an overly generous payment for these sorry few teeth, but it was still not what Izîl was hoping for.

“So much digging,” he moaned. “And for what? Paper with pictures of the dead king? Always the dead staring at me.” His voice dropped. “I can’t keep it up, Karou. I’m broken. I can barely hold a shovel anymore. I scrabble at the hard earth, digging like a dog. I’m through.”

Pity hit her hard. “Surely there are other ways to live—”

“No. Only death remains. One should die proudly when it is no longer possible to live proudly. Nietzsche said that, you know. Wise man. Large mustache.” He tugged at his own bedraggled mustache and attempted a smile.

“Izîl, you can’t mean you want to die.”

“If only there was a way to be free…”

“Isn’t there?” she asked earnestly. “There must be something you can do.”

His fingers twitched, fidgeting with his mustache. “I don’t like to think of it, my dear, but… there is a way, if you would help me. You’re the only one I know who’s brave enough and good enough—Ow!” His hand flew to his ear, and Karou saw blood seep through his fingers. She shrank back. Razgut must have bitten him. “I’ll ask her if I want, monster!” cried the graverobber. “Yes, you are a monster! I don’t care what you once were. You’re a monster now!”

A peculiar tussle ensued; it looked as if the old man were wrestling with himself. The waiter flapped nearby, agitated, and Karou scraped her chair back clear of flailing limbs both visible and invisible.

“Stop it. Stop!” Izîl cried, wild-eyed. He braced himself, raised his walking stick, and brought it back hard against his own shoulder and the thing that perched there. Again and again he struck, seeming to smite himself, and then he let out a shriek and fell to his knees. His walking stick clattered away as both hands flew to his neck. Blood was wicking into the collar of his djellaba—the thing must have bitten him again. The misery on his face was more than Karou could bear and, without stopping to consider, she dropped to his side, taking his elbow to help him up.

A mistake.

At once she felt it on her neck: a slithering touch. Revulsion juddered through her. It was a tongue. Razgut had gotten his taste. She heard a loathsome gobbling sound as she lurched away, leaving the graverobber on his knees.

That was enough for her. She gathered up the teeth and her sketchbook.

“Wait, please,” Izîl cried. “Karou. Please.”

His plea was so desperate that she hesitated. Scrabbling, he dug something from his pocket and held it out. A pair of pliers. They looked rusted, but Karou knew it wasn’t rust. These were the tools of his trade, and they were covered in the residue of dead mouths. “Please, my dear,” he said. “There isn’t anyone else.”

She understood at once what he meant and took a step back in shock. “No, Izîl! God. The answer is no.”

“A bruxis would save me! I can’t save myself. I’ve already used mine. It would take another bruxis to undo my fool wish. You could wish him off me. Please. Please!”

A bruxis. That was the one wish more powerful than a gavriel, and its trade value was singular: The only way to purchase one was with one’s own teeth. All of them, self-extracted.

The thought of pulling her own teeth out one by one made Karou feel woozy. “Don’t be ridiculous,” she whispered, appalled that he would even ask it. But then, he was a madman, and right now he certainly looked it.

She retreated.

“I wouldn’t ask, you know I wouldn’t, but it’s the only way!”

Karou walked rapidly away, head down, and she would have kept walking and not looked back but for a cry that erupted behind her. It burst from the chaos of the Jemaa el-Fna and instantly dwarfed all other noise. It was some mad kind of keening, a high, thin river of sound unlike anything she had ever heard.

It was definitely not Izîl.

Unearthly, the wail rose, wavering and violent, to break like a wave and become language—susurrous, without hard consonants. The modulations suggested words, but the language was alien even to Karou, who had more than twenty in her collection. She turned, seeing as she did that the people around her were turning, too, craning their necks, and that their expressions of alarm were turning to horror when they perceived the source of the sound.

Then she saw it, too.

The thing on Izîl’s back was invisible no more.