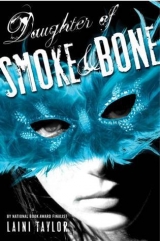

Текст книги "Daughter of Smoke & Bone"

Автор книги: Лэйни Тейлор

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

52

52

M ADNESS

The living tide sucked them into the agora, a backwash of elbows and wings, horns and hide, fur and flesh, and she was carried along, stricken dumb with disbelief, her hooves scarcely skimming the cobbles.

A seraph, inside Loramendi.

Not a seraph. This seraph. Whom she had touched. Saved. Here, in the Cage, his hands on her arms, hot even through the leather of his gloves, this angel who was alive because of her.

He was here.

It was such madness, it made a churning of her thoughts, more chaotic than the churning all around her. She couldn’t think. What could she say? What should she do?

Later it would strike her that not for an instant had she considered doing what anyone else in the entire city would have done without a thought: unmasking him and screaming, “Seraph!”

She drew a long, uneven breath and said, “You’re mad to be here. Why did you come?”

“I told you, I came to thank you.”

She had a terrible thought. “Assassination? You’ll never get close to the Warlord.”

Earnestly, he said, “No. I wouldn’t tarnish the gift you gave me with the blood of your folk.”

The agora was a massive oval; it was big enough for an army to mass, many phalanxes abreast, but tonight there were no troops at its center, only dancers moving in the intricate patterns of a lowland reel. Those spilling from the Serpentine eddied out around the edges of the square where the density of bodies was greatest. Casks of grasswine stood amid tables laden with food, and folk gathered in clusters, children on their shoulders, everyone laughing and singing.

Madrigal and the angel were still caught in the churning delta of the Serpentine. He was anchoring her, as steady as a breakwall. In the blank, gasping aftermath of shock, Madrigal didn’t try to move away.

“Gift?” she said, incredulous. “You hold that gift lightly, coming here, into certain death.”

“I’m not going to die,” he said. “Not tonight. A thousand things might have stopped me from being here right now, but instead, a thousand things brought me here. Everything lined up. It has been easy, as if it were meant—”

“Meant!” she said, amazed. She spun to face him, which, in the crush, brought her against his chest as if they were still dancing. She fought backward for space. “As if what were meant?”

“You,” he said. “And me.”

His words sucked the breath from her lungs. Him and her? Seraph and chimaera? It was preposterous. All she could think to say was, again, “You’re mad.”

“It’s your madness, too. You saved my life. Why did you do it?”

Madrigal had no answer. For two years she had been haunted by it, by the feeling, when she had found him dying, that somehow he was hers to protect. Hers. And now here he was, alive and, impossibly, here. She was still grappling with disbelief, that it was him, his face—of which she remembered every plane and angle—hidden behind that mask.

“And tonight,” he said, “a million souls in the city, I might not have found you at all. I might have searched all night and never so much as glimpsed you, but instead, there you were, like you were set down in front of me, and you were alone, moving through the crowd and apart in it, like you were waiting for me….”

He went on speaking, but Madrigal stopped hearing. At his mention of her apartness, the reason for it came thundering back to her, having been momentarily forgotten in her shock. Thiago. She looked to the palace, up at the Warlord’s balcony. At this distance, the figures on it were only silhouettes, but they were silhouettes she knew: the Warlord, the hulking shape of Brimstone, and a gaggle of the ruler’s antlered wives. Thiago was not there.

Which could only mean he was down here. A thrill of fear shot through her from hooves to horns. “You don’t understand,” she said, pirouetting to scan the crowd. “There was a reason no one was dancing with me. I thought you were brave. I didn’t know you were mad—”

“What reason?” the angel asked, still near. Still too near.

“Trust me,” she said, urgent. “It isn’t safe for you. If you want to live, leave me.”

“I’ve come a long way to find you—”

“I’m spoken for,” she blurted, hating the words even before they were out.

This brought him up short. “Spoken for? Betrothed?”

Claimed, she thought, but she said, “As good as. Now go. If Thiago sees you—”

“Thiago?” The angel recoiled at the name. “You’re betrothed to the Wolf?”

And at the moment he pronounced those words—the Wolf—arms came around Madrigal’s waist from behind and she gasped.

In an instant, she saw what would happen. Thiago would discover the angel, and he wouldn’t just kill him, he would make a spectacle of it. A seraph spy at the Warlord’s ball—such a thing had never happened! He would be tortured. He would be made to wish that he had never lived. It all flashed through her, and horror rose like bile in her throat. When she heard, close to her ear, a giggle, the relief almost left her limp.

It wasn’t Thiago, but Chiro. “There you are,” said her sister. “We lost you in the crush!”

Madrigal’s blood made a roaring in her ears, and Chiro glanced from her to the stranger, whose heat suddenly felt to Madrigal like a beacon. “Hello,” Chiro said, peering with curiosity at the horse mask, through which Madrigal could still make out the orange burn of his tiger’s eyes.

It hit her anew that he had come in such thin disguise into the den of the enemy for her, and she felt a queer constriction in her chest. For two years she had reflected on Bullfinch as a momentary madness, though it hadn’t felt like madness then, and it didn’t now, to wish this seraph to live—and she did wish it. She pulled herself together and turned to Chiro. Nwella was right behind her.

“Some friends you are,” she chided them. “To dress me like this and then abandon me to the Serpentine. I might have been mauled.”

“We thought you were behind us,” said Nwella, breathless from dancing.

“I was,” said Madrigal. “Far behind you.” She had turned her back on the angel without a second glance. She began to casually herd her friends away from him, using the motion of the crowd to put space between them.

“Who was that?” Chiro asked.

“Who?” asked Madrigal.

“In the horse mask, dancing with you.”

“I wasn’t dancing with anyone. Or perhaps you didn’t notice: No one would dance with me. I am a pariah.”

Scoffing, “A pariah! Hardly. More like a princess.” Chiro threw a skeptical look back, and Madrigal was wild to know what she saw. Was the angel looking after them, or had some sense of self-preservation kicked in and made him disappear?

“Have you seen Thiago yet?” Nwella asked. “Or rather, has he seen you?”

“No—” Madrigal started to say, but then Chiro burst out with, “There he is!” and she went cold.

There he was.

He was unmistakable, with the hewn-off wolf head atop his own, his grotesque version of a mask. Its fangs curved over his brow, its muzzle drawn back in a snarl. His snow-white hair was brushed and arranged over his shoulders, his vest ivory satin—so much white, white upon white, framing his strong, handsome face, which was bronzed by the sun, making his pale eyes seem ghostly.

He hadn’t seen her yet. The crowd parted around him, not even the drunkest of the revelers failing to recognize him and make way. The mob seemed to shrivel as he passed with his retinue, who were of true wolf aspect, and moved like a pack.

The meaning of this night caught up to Madrigal: her choice, her future.

“He’s magnificent,” breathed Nwella, clinging to Madrigal on one side. Madrigal had to agree, but she placed the credit for it with Brimstone, who had crafted that beautiful body, not with Thiago, who wore it with the arrogance of entitlement.

“He’s looking for you,” said Chiro, and Madrigal knew she was right. The general was unhurried, his pale eyes sweeping the crowd with the confidence of one who gets what he wants. Then his gaze came to rest on her. She felt impaled by it. Spooked, she took a step back.

“Let’s go dance,” she blurted, to the surprise of her friends.

“But—” Chiro said.

“Listen.” A new reel was starting up. “It’s the Furiant. My favorite.”

It was not her favorite, but it would do. Two lines of dancers were forming, men on one side, women on the other, and before Chiro and Nwella could say another word, Madrigal had spun to flee toward the women’s file, feeling Thiago’s gaze on the back of her neck like the touch of claws.

She wondered: What of other eyes?

The Furiant began with a light-footed promenade, Chiro and Nwella rushing to join in, and Madrigal went through the steps with grace and a smile, not missing a beat, but she was barely there. Her thoughts had flown outward, darting and dipping with the hummingbird-moths that flocked by the thousands to the lanterns hanging overhead, as she wondered, with a wild, timpani heart, where her angel had gone.

53

53

L OVE I S AN E LEMENT

In the patterns of the Furiant, no one bypassed Madrigal’s hand as they had in the Serpentine—it would have been too obvious a slight—but there was a formal stiffness in her partners as she passed from one to the next, some barely skimming her fingertips with their own when they were meant to be clasping hands.

Thiago had come up and stood watching. Everyone felt it, and the gaiety of the dance was tamped down. It was his effect, but it was her fault, Madrigal knew, for running from him and trying to hide here, as if it were possible to hide.

She was just buying time, and the Furiant was good for that at least, as it went on a full quarter of an hour, with constant shifts in partner. Madrigal went from a courteous elder soldier with a rhinoceros horn to a centaur to a high-human in a dragon mask who scarcely touched her, and with each revolution she was brought past Thiago, whose eyes never left her. Her next partner’s mask was tiger, and when he took her hand… he actually took her hand. He clasped it firmly in his own gloved hand. A thrill went up Madrigal’s arm from the warming touch, and she didn’t have to look at his eyes to know who it was.

He was still here—and with Thiago so near. Reckless, she thought, electrified by his nearness. After a moment, steadying her breathing and her heart, she said, “Tiger suits you better than horse, I think.”

“I don’t know what you mean, lady,” he replied. “This is my true face.”

“Of course.”

“Because it would be foolish to still be here, if I were who you thought.”

“It would. One might suppose you had a death wish.”

“No.” He was solemn. “Never that. A life wish, if anything. For a different sort of life.”

A different sort of life. If only, Madrigal thought, her own life and choices—or lack of them—hemming her in. She kept her voice light. “You wish to be one of us? I’m sorry, we don’t accept converts.”

He laughed. “Even if you did, it wouldn’t help. We are all locked in the same life, aren’t we? The same war.”

In a lifetime of hating seraphim, Madrigal had never thought of them as living the same life as she, but what the angel said was true. They were all locked in the same war. They had locked the entire world in it. “There is no other life,” she said, and then she tensed, because they had come around to the place where Thiago stood.

The pressure of the angel’s grip on her hand increased ever so slightly, gently, and it helped her bear up under the general’s gaze until she turned away from it again, and could breathe.

“You need to go,” she said quietly. “If you’re discovered…”

The angel let a beat pass in silence before asking, just as quietly, “You’re not really going to marry him, are you?”

“I… I don’t know.”

He lifted her hand so that she could circle beneath the bridge of their arms; it was a part of the pattern, but her height and horns interfered, and they had to release fingers and join them again after the spin.

“What is there to know?” he asked. “Do you love him?”

“Love?” The question was a surprise, and a laugh escaped Madrigal’s lips. She quickly composed herself, not wanting to draw Thiago’s scrutiny.

“It’s a funny question?”

“No,” she said. “Yes.” Love Thiago? Could she? Maybe. How could you know a thing like that? “What’s funny is that you’re the first one to ask me that.”

“Forgive me,” said the seraph. “I didn’t realize that chimaera don’t marry for love.”

Madrigal thought of her parents. Her memory of them was hazed with a patina of years, their faces blurred to generalities—would she even know them, if she found them?—but she did remember their simple fondness for each other, and how they had seemed always to be touching. “We do.” She wasn’t laughing now. “My parents did.”

“So you are a child of love. It seems right, that you were made by love.”

She had never thought of herself in that way, but after he said it, it struck her as a fine thing, to have been made by love, and she ached for what she had lost, in losing her family. “And you? Did your parents love each other?”

She heard herself ask it, and was overcome by the dizzying surreality of the circumstance. She had just asked a seraph if his parents loved each other.

“No,” he said, and offered no explanation. “But I hope that my children’s parents will.”

Again he lifted her hand so that she could circle under the bridge made by their arms, and again her horns got in the way, so they were briefly parted. Turning, Madrigal felt a sting in his words, and when they were facing each other once more, she said, in her defense, “Love is a luxury.”

“No. Love is an element.”

An element. Like air to breathe, earth to stand on. The steady certainty of his voice sent a shiver through her, but she didn’t get a chance to respond. They had concluded their pattern, and she still had gooseflesh from the effect of his extraordinary statement as he handed her on to her next partner, who was drunk and uttered not a syllable for the entirety of their contact.

She tried to keep track of the seraph. He should have partnered Nwella after herself, but by then he was gone, and she saw no tiger mask in the whole of the array. He had melted away, and she felt his absence like a space cut from the air.

The Furiant wound down to its final promenade, and when it ended in a brazen gypsy tinkling of tambourines, Madrigal was delivered, as if it had been orchestrated that way, virtually into the White Wolf’s arms.

54

54

M EANT

“My lord,” Madrigal’s throat went dry so her words were a rasp, near enough a throaty whisper to be mistaken for one.

Nwella and Chiro crowded behind her, and Thiago smiled, lupine, the tips of fangs appearing between his full red lips. His eyes were bold. They didn’t meet hers, but roved lower, with no effort at subtlety. Madrigal’s skin went hot as her heart grew cold, and she dropped into a curtsy from which she wished that she never had to rise and meet his eyes, but rise she must, and did.

“You’re beautiful tonight,” said Thiago. Madrigal needn’t have worried about meeting his eyes. If she had been headless, he would not yet have noticed. The way he was looking at her body in the midnight sheath made her want to cross her arms over her chest.

“Thank you,” she said, fighting the impulse. A return of compliment was called for, so she said simply, “As are you.”

He looked up then, amused. “I am beautiful?”

She inclined her head. “As a winter wolf, my lord,” she said, which pleased him. He seemed relaxed, almost lazy, his eyes heavy-lidded. He was entirely sure of her, Madrigal saw. He wasn’t looking for a gesture; there was not the smallest kernel of uncertainty in him. Thiago got what he wanted. Always.

And would he tonight?

A new tune struck up, and he tilted his head to acknowledge it. “The Emberlin,” he said. “My lady?” He held out his arm to her, and Madrigal went still as prey.

If she took his arm, did that mean it was done, that she accepted him?

But to refuse it would be the grossest of slights; it would shame him, and one simply did not shame the White Wolf.

It was an invitation to dance, and it felt like a trap, and Madrigal stood paralyzed a beat too long. In that beat she saw Thiago’s gaze sharpen. His easy lethargy fell away to be replaced by… she wasn’t sure. It didn’t have time to take form. Disbelief, perhaps, which would have given way in its turn to ice-cold fury had not Nwella, with a panicked squeak, placed her palm in the small of Madrigal’s back and shoved.

Thus propelled, Madrigal took a step, and there was nothing for it. She didn’t take Thiago’s arm so much as she collided with it. He tucked hers beneath his own, proprietary, and escorted her into the dance.

And certainly, as everyone thought, into the future.

He grasped her by the waist, which was the proper form of the Emberlin, in which the men lifted the ladies like offerings to the sky. Thiago’s hands almost completely encircled her slim midriff, his claws on her bare back. She felt the point of each one on her skin.

There was some talk between them—Madrigal must have asked after the Warlord’s health, and Thiago must have answered, but she could scarcely have related what was said. She might have been a sugared shell, for all that she was present in her skin.

What had she done? What had she just done?

She couldn’t even fool herself that it was the product of an instant and Nwella’s tiny shove. She had let herself be dressed like this; she had come here; she had known. She might not have admitted to herself that she knew what she was doing, but of course she had. She had let herself be carried along on the certainty of others. There had been a piquant satisfaction in being chosen… envied. She was ashamed of it now, and of the way she had come here tonight, ready to play the trembling bride, and accept a man she did not love.

But… she had not accepted him, and she thought now that she wouldn’t have. Something had changed.

Nothing had changed, she argued with herself. Love is an element, indeed. The angel coming here, the risk of it! It stunned her, but it changed nothing.

And where was he now? Each time Thiago lifted her she glanced around, but she saw no horse or tiger mask. She hoped he had gone, and was safe.

Thiago, who up until now had seemed satisfied with what his hands could hold, must have sensed that he was not commanding her attention. Bringing her down from a lift, he intentionally let her slip so he had to catch her against him. At the surprise, her wings spontaneously sprang open, like twin spinnakers filling with wind.

“My apologies, my lady,” Thiago said, and he eased her down so her hooves found the ground again, but he didn’t loosen his hold on her. She felt the rigid surface of his muscled chest against her own chest. The wrongness of it stirred a panic that she had to fight down to keep from wrenching herself from his arms. It was hard to fold her wings again, when what she really wanted to do was take flight.

“This gown, is it cut from shadow?” the general asked. “I can barely feel it between my fingers.”

Not for want of trying, thought Madrigal.

“Perhaps it is a reflection of the night sky,” he suggested, “skimmed from a pond?”

She supposed that he was being poetic. Erotic, even. In return, as unerotically as possible—more like complaining of a stain that wouldn’t come out—she said, “Yes, my lord. I went for a dip, and the reflection clung.”

“Well. Then it might slip away like water at any moment. One wonders what, if anything, is beneath it.”

And this is courtship, thought Madrigal. She blushed, and was glad of her mask, which covered all but her lips and chin. Choosing not to address the matter of her undergarments, she said, “It is sturdier than it looks, I assure you.”

She did not intend a challenge, but he took it as one. He reached up to the delicate threads that, like gossamers of a spider’s web, secured the gown around her neck, and gave a short, sharp tug. They gave way easily to his claws, and Madrigal gasped. The dress stayed in place, but a cluster of its fragile fastenings were severed.

“Or perhaps not so sturdy,” said Thiago. “Don’t worry, my lady, I’ll help you hold it up.”

His hand was over her heart, just above her breast, and Madrigal trembled. She was furious at herself for trembling. She was Madrigal of the Kirin, not some blossom caught in a breeze. “That’s kind of you, my lord,” she replied, shrugging off his hand as she stepped away. “But it is time to change partners. I’ll have to manage my gown on my own.”

She had never been so glad to be handed on to a new partner. In this case it was a bull-moose of a man, graceless, who came near to treading on her hooves any number of times. She barely noticed.

A different sort of life, she thought, and the words became a mantra to the melody of the Emberlin. A different sort of life, a different sort of life.

Where was the angel now, she wondered. Yearning suffused her, full as flavor, like chocolate melting on her tongue.

Before she knew it, the bull-moose was returning her to Thiago, who claimed her with his clutching hands and pulled her into him.

“I missed you,” he said. “Every other lady is coarse next to you.”

He talked to her in that bedroom purr of his, but all she could think was how clumsy, how effortful his words seemed after the angel’s.

Twice more Thiago passed her to new partners, and twice she was returned to him in due course. Each time was more unbearable than the last, so that she felt like a runaway returned home against her will.

When, turned over to her next partner, she felt the firm pressure of leather gloves enfold her fingers, it was with a lightness like floating that she let herself be swept away. Misery lifted; wrongness lifted. The seraph’s hands came around her waist and her feet left the ground and she closed her eyes, giving herself over to feeling.

He set her back down, but didn’t let her go. “Hello,” she whispered, happy.

Happy.

“Hello,” he returned, like a shared secret.

She smiled to see his new mask. It was human and comical, with jug ears and a red drunkard’s nose. “Yet another face,” she said. “Are you a magus, conjuring masks?”

“No conjuring needed. There are as many masks to choose from as there are revelers passed out drunk.”

“Well, this one suits you least of all.”

“That’s what you think. A lot can happen in two years.”

She laughed, remembering his beauty, and was seized by a desire to see his face again.

“Will you tell me your name, my lady?” he asked.

She did, and he repeated it—“Madrigal, Madrigal, Madrigal”—like an incantation.

How odd, Madrigal thought, that she should be overcome by such a feeling of… fulfillment… from the simple presence of a man whose name she didn’t know and whose face she couldn’t see. “And yours?” she asked.

“Akiva.”

“Akiva.” It pleased her to say it. She may have been the one whose name meant music, but his sounded like it. Saying it made her want to sing it, to lean out a window and call him home. To whisper it in the dark.

“You’ve done it, then,” he said. “Accepted him.”

Defiantly, she replied, “No. I have not.”

“No? He’s watching you like he owns you.”

“Then you should certainly be elsewhere—”

“Your dress,” he said, noticing it. “It’s torn. Did he—?” Madrigal felt heat, a ripple of anger flashing off him like a draft off a bonfire.

She saw that Thiago was dancing with Chiro, and was staring right between Chiro’s sharp jackal ears at her. She waited until the revolutions of the dance brought Akiva’s broad back between them, shielding her face, before answering. “It’s nothing. I’m not used to wearing such fragile fabric. This was chosen for me. I crave a shawl.”

He was tense with anger but his hands remained gentle at her waist. He said, “I can make you a shawl.”

She cocked her head. “You knit? Well. That’s an unusual accomplishment in a soldier.”

“I don’t knit,” he said, and that’s when Madrigal felt the first feather-soft touch on her shoulder. She didn’t mistake it for Akiva’s touch, because his hands were at her waist. She looked down and saw that a gray-green hummingbird-moth had settled on her, one of the many fluttering overhead, drawn to the expansiveness of lantern light that must seem like a universe to them. The feathers of its tiny bird body gleamed, jewel-like, as its furred moth wings fanned against her skin. It was followed shortly by another, this one pale pink, and another, also pink, with orange eyespots on its lacework wings. More floated out of the air, and in a moment, a fine company of them covered Madrigal’s chest and shoulders.

“There you are, my lady,” said Akiva. “A living shawl.”

She was amazed. “How—? You are a magus.”

“No. It’s a trick, only.”

“It’s magic.”

“Not the most useful magic, herding moths.”

“Not useful? You made me a shawl.” She was awed by it. The magic she knew through Brimstone had little whimsy in it. This was beautiful, both in form—the wings were a dozen twilight colors, and as soft as lamb’s ears—and in purpose. He had covered her. Thiago had torn her dress, and Akiva had covered her.

“They tickle.” She laughed. “Oh no. Oh.”

“What is it?”

“Oh, make them go.” She laughed harder, feeling tiny tongues dart from tiny beaks. “They’re eating my sugar.”

“Sugar?”

The tickling made her wriggle her shoulders. “Make them go. Please.”

He tried to. A few lifted away and made a circle around her horns, but most stayed where they were. “I’m afraid they’re in love,” he said, concerned. “They don’t want to leave you.” He lifted one hand from her waist to gently brush a pair from her neck, where their wings fanned against her jaw. Melancholy, he said, “I know just how they feel.”

Her heart, like a fist clenching. The time had come for Akiva to lift her again, and he did, though her shoulders were still cloaked in moths. From above the heads of the crowd, she was grateful to see that Thiago was turned away. Chiro, though, whom he was lifting, saw her and did a double take.

Akiva brought Madrigal back down, and just before her feet touched ground they looked at each other, mask to mask, brown eyes to orange, and a surge went between them. Madrigal didn’t know if it was magic, but most of the hummingbird-moths took flight and swirled away as if carried by a wind. She was down again, her feet moving, her heart racing. She had lost track of the pattern, but she sensed that it was drawing to its conclusion and that, any second, she would come around again to Thiago.

Akiva would have to hand her back into the general’s keeping.

Her heart and body were in revolt. She couldn’t do it. Her limbs were light, ready to flee. Her heartbeat sped to a fast staccato, and the remnants of her living shawl burst from her as if spooked. Madrigal recognized the signs in herself, the readying, the outward calm and inner turmoil, the rushing that filled her mind before a charge in battle.

Something is going to happen.

Nitid, she thought, did you know all along?

“Madrigal?” asked Akiva. Like the hummingbird-moths, he sensed the change in her, her quickened breath, the muscles gone taut where his warm hands encircled her waist. “What is it?”

“I want…” she said, knowing what she wanted, feeling pulled toward it, arching toward it, but hardly knowing how to say it.

“What? What do you want?” Akiva asked, gentle but urgent. He wanted it, too. He inclined his head so that his mask came briefly against her horn, sparking a flare of sensation through her.

The White Wolf was only wingspans away. He would see. If she tried to flee, he would follow. Akiva would be caught.

Madrigal wanted to scream.

And then, the fireworks.

Later, she would recall what Akiva had said about everything lining up, as if it were meant. In all that was to happen, there would be that feeling of inevitability and rightness, and the sense that the universe was conspiring in it. It would be easy. Starting with the fireworks.

Light blossomed overhead, a great and brilliant dahlia, a pinwheel, a star in nova. The sound was a cannonade. Drummers on the battlements. Black powder bursting in the air. The Emberlin broke apart as dancers shucked masks and threw back their heads to look up.

Madrigal moved. She took Akiva’s hand and ducked into the moil of the crowd. She kept low and moved fast. A channel seemed to open for them in the surge of bodies, and they followed it, and it carried them away.