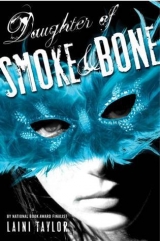

Текст книги "Daughter of Smoke & Bone"

Автор книги: Лэйни Тейлор

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Revenants—as the resurrected were called—didn’t have to tithe pain for power; it was already done. The hamsas were a magical weapon paid for with the pain of their last death.

It was the lot of soldiers to die again and again. “Death, death, and death,” as Chiro put it. There were just never enough of them. New soldiers were always coming up—the children of Loramendi and all of the free holdings, trained from the time they could grip a weapon—but the battle tolls were high. Even with resurrection, chimaera existed at the edge of annihilation.

“The beasts must be destroyed,” thundered Joram after his every address to his war council; the angels were like the long shadow of death, and all chimaera lived in its chill.

When the chimaera won a battle, the gleaning was easy. The survivors went over land and city for all the corpses of the slain and drew out every soul to bring back to Brimstone. When they were defeated, though they risked death to save the souls of their fallen comrades, many were left behind and lost forever.

The incense in the thuribles lured the souls from their bodies. In a thurible, properly sealed, souls could be preserved indefinitely. In the open, prey to the elements, it was only a matter of days before they evanesced, teased apart like breath on wind, and ceased to exist.

Evanescence was not, in itself, a grim fate. It was the way of things, to be unmade; it happened in natural death, every day. And to a revenant who had lived in body after body, died death after death, evanescence could seem like a dream of peace. But the chimaera could ill afford to let soldiers go.

“Would you want to live forever,” Brimstone had asked Madrigal once, “only to die again and again, in agony?”

And over the years, she saw what it did to him, to thrust that fate on so many good creatures who were never let to go to their rest, how it bowed his head and wearied him and left him staring and morose.

Becoming a revenant was what Chiro spoke of, hard-eyed, while Madrigal tried to decide whether to marry Thiago. It was a fate she could choose now to escape. Thiago wanted her “pure”; he would see that she stayed that way—already, he was manipulating his commanders to keep her battalion away from danger. If she chose him, she would never bear the hamsas. She would never go into battle again.

And maybe that would be for the best—for herself, and for her comrades, too. She alone knew how unfit she was for it. She hated to kill—even angels. She had never told anyone what she’d done at Bullfinch two years earlier, sparing that seraph’s life. And not just sparing it, but saving it! What madness had come over her? She had bound his wound. She had caressed his face. A wave of shame always rose in her at the memory—at least she chose to call it shame that quickened her pulse and flushed her face with delicate color.

How hot the angel’s skin had been, like fever, and his eyes, like fire.

She was haunted with wondering if he had lived. She hoped he had not, and that any evidence of her treason had died right there, in the Bullfinch mist. Or so she told herself.

It was only in moments of waking, with the lace edge of a dream still light in her grasp, that the truth came clear. She dreamed the angel alive. She hoped him alive. She denied it, but it persisted, rising in flashes to startle her, always accompanied by a quickening of the blood, a flush, and strange, rushing frissons of sensation all the way to her fingertips.

She sometimes thought that Brimstone knew. Once or twice when the memory had caught her unaware, that rush and shiver, he had looked up from his work as if something had captured his attention. Kishmish, perched on his horn, would look, too, and both of them would stare at her unblinking. But whatever Brimstone knew or didn’t know, he never said a word about it, just as he didn’t say a word about Thiago, though he had to know that Madrigal’s choice was heavy in her mind.

And that evening, at the ball, it would be decided, one way or the other.

Something is going to happen.

But what?

She told herself that when she stood before Thiago, she would know what to do. Blush and curtsy, dance with him, play the shy maiden while smiling an unmistakable invitation? Or stand aloof, ignore his advances, and remain a soldier?

“Come on,” said Chiro, shaking her head as if Madrigal were a lost cause. “Nwella will have something you can wear, but you’ll have to take what she gives you, and no complaining.”

“All right,” sighed Madrigal. “To the baths, then. To make ourselves shiningly clean.”

Like vegetables, she thought, before they go in the stew.

50

50

S UGARED

“No,” said Madrigal, looking in the mirror. “Oh no. No no. No.”

Nwella did indeed have a gown for her. It was midnight-blue shot silk, a form-skimming sheath so fine it felt like a touch could dissolve it. It was arrayed with tiny crystals that caught the light and beamed it back like stars, and the whole back was open, revealing the long white channel of Madrigal’s spine all the way to her tailbone. It was alarming. Back and shoulders and arms and chest. Far too much chest. “No.” She started to shrug out of it, but Chiro stopped her.

“Remember what I said: no complaining.”

“I take it back. I reserve my right to complain.”

“Too late. It’s your fault, anyway. You had a week to get a gown. You see what happens when you dither? Others make your choices for you.”

Madrigal thought that she wasn’t talking about the gown. “What? Is this a punishment, then?”

At her other side, Nwella chuffed. She was a frail thing of lizard aspect who had been with Madrigal and Chiro at school, but parted from them when they went to battle training and she into royal service. “Punishment? Making you stunning, you mean? Look at yourself.”

Madrigal did look, and what she saw was skin. The most delicate interweaving of individual silk strands climbed around her neck, invisibly holding the gown to her body. “I look naked.”

“You look astonishing,” said Nwella, who was seamstress to the Warlord’s younger wives, the very youngest of whom were, to put it kindly, unyoung. The Warlord had seen fit to stop imposing himself on new brides some centuries earlier. Like Brimstone, he was of natural flesh, and looked it. Thiago, his firstborn, was some hundreds of years old, though he wore the skin of a young man, and the hamsas to go with it.

As Madrigal had said, the general’s fetish for purity was hypocrisy: He himself had been through many resurrections, and his hypocrisy was twofold—not only was he not “pure,” he had not been born high-human.

The Warlord was Hartkind, with a stag’s head: creature aspect, as were his wives, and so had been Thiago, originally. It wasn’t that it was unusual for a revenant to resurrect in a body unlike his or her natural one; Brimstone couldn’t always match them. It was a matter of time and tooth supply. But Thiago’s bodies were another matter. They were crafted to his precise specifications, and even before they were needed, so that he could examine them for flaws and give his approval. She had seen it once: Thiago checking over a naked replica of himself—the husk that would receive him the next time he died. It had been macabre.

She tested her gown with little tugs, feeling certain that too heavy a hand in dancing could pull it clean off. “Nwella,” she implored, “don’t you have something more… substantial?”

“Not for you,” Nwella said. “A figure like that, why would you want to cover it?” She whispered something to Chiro.

“Stop conspiring,” Madrigal said. “Can’t I have a shawl at least?”

“No,” they said together.

“I feel almost as naked as at the baths.”

She had never in her life felt so exposed as when she’d walked through the steam and thigh-deep water with Chiro that afternoon. Everyone knew now that she was Thiago’s choice, and every pair of eyes in the women’s bath had inspected her, so that she wanted to sink down out of sight, leaving just her horns spiking through the surface of the water.

“Let Thiago see what he’s getting,” Nwella said, devilish.

Madrigal stiffened. “Who said he’s getting it?” It, she heard herself say. The word felt appropriate, as if she were some inanimate thing, a gown on a hanger. “Me,” she corrected. “Who said he’s getting me?”

Nwella laughed off the idea that Madrigal might refuse him. “Here.” She came forward with a mask. “We will permit you to cover your face.” It was a bird with its wings spread, carved of lightweight kaza wood, black and embellished with dark feathers that fanned out from the sides of her face. In shifts of light, rainbows of iridescence rippled over the feathers.

“Ah. Good. No one will know who I am now,” Madrigal remarked, wry. Her wings and horns eluded disguise.

The Warlord’s ball was a masquerade, a “come-as-you-aren’t.” Chimaera of human aspect wore the faces of creatures, while those of beast aspect wore carven human likenesses, exaggerated to ridiculous proportion. It was the one night of the year for folly and pretend, the one night that fell outside normal life, but for Madrigal, this year, it was anything but. It was, rather, a night to decide her life.

With a sigh, she gave in to her friends’ ministrations. She sat on a stool and let them define her eyes with kohl, rouge her lips with rose-petal paste, and string lengths of ultrafine gold chain between her horns in tiers, suspended with tiny crystal drops that winked in the light. Chiro and Nwella giggled as if they were preparing a bride for her wedding night, and it struck Madrigal that it well could be, if not in ceremony, at least in one way.

If she accepted Thiago, it was unlikely she would be returning to the barracks tonight.

She shivered, imagining his clawed hands on her flesh. What would it be like? She had never made love—in that way, too, she was “pure,” as she imagined Thiago must know. She thought about it, of course she thought about it. She was of age; her body coursed with urges, just like anyone’s, and chimaera weren’t puritanical about sex. Madrigal had just never come to a moment when it had felt right.

“There. You’re finished,” said Chiro. She and Nwella pulled Madrigal to her feet and stood back from her to survey their work. “Oh,” breathed Nwella. There was a pause, and when Chiro spoke again, her voice was flat. She said, “You’re beautiful.”

It didn’t sound like a compliment.

After Kalamet, when Chiro had awakened in the cathedral, Madrigal was there beside her. “You’re all right,” she assured her, as Chiro’s eyes fluttered open. It was Chiro’s first resurrection, and revenants said it could be disorienting. Madrigal hoped that in matching the new body so closely to her sister’s original flesh, she could ease her transition. “You’re all right,” she said again, clasping Chiro’s hand with its hamsa, symbol of her new status. She told her, “Brimstone let me make your body. I used diamonds.” Conspiratorial. “Don’t tell anyone.”

She helped Chiro sit up. The fur of her cat haunches was soft, and the flesh of her human arms was, too. Jerkily, Chiro touched her new skin—hips, ribs, human breasts. Her hand climbed eagerly up her neck to her head, felt the fur there, and the jackal muzzle, and froze.

The sound she made was like choking, and at first Madrigal thought it was only the problem of a newly made throat and a mouth that had never yet formed speech. But it wasn’t.

Chiro threw off Madrigal’s hand. “You did this?”

Madrigal backed up a step. “It’s… it’s perfect,” she said, faltering. “It’s almost exactly like your real—”

“And that’s all I merit? Beast aspect? Thank you, my sister. Thank you.”

“Chiro—”

“You couldn’t have made me high-human? What are a few teeth to you? To Brimstone?”

The idea had never even entered Madrigal’s mind. “But… Chiro. This is you.”

“Me.” Her voice was changed; it had a deeper tone than her original voice, and Madrigal couldn’t tell how much of this was its newness, but whatever else it was, it was acid, and ugly. “Would you want to be me?”

Hurt and confused, Madrigal said, “I don’t understand.”

“No, you wouldn’t,” said Chiro. “You’re beautiful.”

Later, she had apologized. It was the shock, she said. The new body had felt tight, unyielding; she could barely breathe. Once she grew accustomed to it, she praised its strength, its lithe movement. She could fly faster than before; her movements were whip-quick, her teeth and eyesight sharper. She said she was like a violin that had been tuned—the same, but better.

“Thank you, my sister,” she said, and seemed to mean it.

But Madrigal remembered the spiteful way she had said, “You’re beautiful.” She sounded like that now.

Nwella was more exuberant. “So beautiful!” she sang. A frown creased her scaled brow, and she plucked at the charm that hung around Madrigal’s neck. “This, of course, will have to go,” she said, but Madrigal pulled away.

“No,” she said, closing her hand around it.

“Just for tonight, Mad,” coaxed Nwella. “It just isn’t fit for the occasion.”

“Leave it,” said Madrigal, and that was that. The tone of her voice dissuaded Nwella from pressing the issue.

“Okay,” she said with a sigh, and Madrigal spilled her wishbone from her cupped palm so that it settled back in its place, where her clavicles met. It wasn’t beautiful or fine, just a bone, and she saw plainly that it did not do justice to her decolletage, but she didn’t care. It was what she wore.

Nwella regarded it, pained, and then turned to rummage in her drawer of cosmetic tubes and ointments. “Here, then. At the very least.” She came up with a silver bowl and a big soft brush, and before Madrigal knew what was happening Nwella had dusted her chest, neck, and shoulders with something that glittered.

“What—?”

“Sugar,” she said, giggling.

“Nwella!” Madrigal tried to brush it off, but it was dust-fine and it clung: sugar powder, which girls wore when they planned to be tasted. If her rose-petal lips and naked back were not enough invitation to Thiago, Madrigal thought, this certainly was. Its telltale shimmer might as well have been a sign that said LICK ME.

“You don’t look like a soldier now,” said Nwella.

It was true. She looked like a girl who had made her choice. Had she? Everyone thought she had, which almost felt like the same thing. But it wasn’t too late. She could decide not to go to the ball at all—that would send quite the opposite message of showing up sugared. She had only to decide what she wanted.

She held herself framed in the mirror for a long beat. She felt dizzy, as if the future were rushing at her.

It was, though at that moment, she could have no notion that it was coming for her with invisible wings and eyes that no mask could disguise, and that her choices, such as they were, would soon be swept away like dust on a wingbeat, leaving in their place the unthinkable.

Love.

“Let’s go,” she said, and she linked arms with Chiro and Nwella, and went out to meet it.

51

51

T HE S ERPENTINE

Loramendi’s main thoroughfare, the Serpentine, became a processional route on the Warlord’s birthday. The custom was to dance its length, moving from partner to masked partner all the way to the agora, the city’s gathering place. The ball was there, under thousands of lanterns strung like stars from the bars of the Cage, making it, for a night, a miniature world with its own firmament.

Madrigal plunged into the crowd with her friends, as she had in years past, but this year, she realized at once, things were different.

She might have been masked, but she was not disguised—her appearance was far too distinctive—and she might have been sugared, but no one took the sparkle of her shoulders as an invitation. They knew she was not for them. In the wild merriment of the street, she was as apart as if she were drifting along in a crystal sphere.

Again and again, Chiro and Nwella were swept into strangers’ embraces and kissed, mask to mask. That was tradition: a spinning, stamping dance punctuated liberally with kisses, to celebrate unity among the races. Musicians were grouped at intervals so that merrymakers were passed from melody to melody as from hand to hand, with never a lull. Wild music spun them along, but no one swept Madrigal up. Several times some soldier started toward her—one even grabbed her hand—but always there was a friend there to pull him back and whisper a warning. Madrigal couldn’t hear what was said, but she could imagine it.

She is Thiago’s.

No one touched her. She drifted through the revelry alone.

Where was Thiago, she wondered, her eyes darting from mask to mask. She would get a glimpse of long white hair or wolf aspect and her heart would jump at the thought that it was him, but each time it was someone else. The long white hair belonged to an old woman, and Madrigal had to laugh at her own skittishness.

Every citizen of Loramendi was in the streets, but somehow space opened around her and she moved alone, following in her friends’ wake toward the agora. Thiago would be there, she guessed, probably standing with his father on the palace balcony, watching the crowd surge as the procession spilled wave after wave of chimaera into the square.

He would be watching for her.

Unconsciously, she slowed her steps. Nwella and Chiro went whirling on ahead in their masks, kissing. For the most part they just touched the lips of their masks to the lips—beaks, muzzles, maws—of other masks, but there were real kisses, too, with no regard to aspect. Madrigal knew what it was like from previous festivals, the grasswine breath of strangers, the nuzzle of a tiger’s whiskered jaw, or a dragon’s, or a man’s. But not tonight.

Tonight, she was in isolation—eyes were on her but not hands, and certainly not lips. The Serpentine seemed a very long stretch to go alone.

Then someone took her elbow. The touch jarred her, coming as it did to end her apartness. Thinking it must be Thiago, she stiffened.

But no. The one at her side wore a horse mask of molded leather that covered his true head completely. Thiago would never wear a horse head, or any other mask to conceal his face. He wore the same thing to the ball every year: a real wolf’s head atop his own, its lower jaw removed so that it made a sort of headdress, its eyes replaced with blue glass, dead and staring.

So who was this? Someone foolish enough to touch her? Well then. He was tall, a head above even her own height, so that Madrigal had to tilt her face up, laying her hand on his shoulder, to nudge his horse muzzle with the beak of her bird mask. A “kiss,” to prove that she still belonged to herself.

And as if some spell had been broken, she was part of the crowd again, spinning in the graceless stamping of the revel, with the stranger for a partner. He moved her along, guarding her from the shoving of larger creatures. She could feel his strength; he might easily have buoyed her without her feet even touching the ground. He ought to have turned her loose after a twirl or two, but he didn’t. His hands—gloved—kept hold of her. And since she didn’t think anyone else would dance with her if he let her go, she didn’t move away. It felt good to be dancing, and she gave herself over to it, and even forgot her anxieties about her dress. Fragile as it seemed, it was holding up fine, and when she whirled it rose in waves around her gazelle hooves, weightless and lovely.

Part of a seething, living tide, they streamed along. Madrigal lost track of her friends, but the horse-masked stranger didn’t abandon her, and when the procession neared the end of the Serpentine, it began to bottleneck. The dancing slowed to a sway and she found herself standing with him, their breathing quick. She looked up, flushed and smiling behind her bird mask, and said, “Thank you.”

“My lady, thank you. The honor is mine.” His voice was rich, his accent strange. Madrigal couldn’t place it. The eastern territories, perhaps.

She said, “You’re braver than the rest, to dance with me.”

“Brave?” His mask was expressionless, of course, but his head quirked to one side, and from his tone, Madrigal realized he didn’t know what she meant. Was it possible he didn’t know who she was—whose she was? He asked, “Are you so ferocious?” and she laughed.

“Terrifying. Apparently.”

Again, that tilt of the head.

“You don’t know who I am.” She was strangely disappointed. She had thought he might be a bold soul, flouting the general fear of Thiago, but it seemed he was only ignorant of the risk.

His head bent toward her, his mask muzzle brushing her ear. In his nearness, there was an aura of warmth. He said, “I know who you are. I came here for you.”

“Did you?” She felt slightly giddy, as if she had been drinking grasswine, though she hadn’t had so much as a sip. “Tell me then, Sir Horse. Who am I?”

“Ah, well, that’s not entirely fair, Lady Bird. You never told me your name.”

“You see? You don’t know. But I have a secret.” She tapped her beak and whispered, smiling, “This is a mask. I am not really a bird.”

He reared back in feigned surprise, though his hand didn’t leave her arm. “Not a bird? I am deceived.”

“So you see, whatever lady you’re looking for, she is all alone somewhere, waiting for you.” She was almost sorry to send him away, but the agora wasn’t far off now. She didn’t want him to catch Thiago’s disfavor, not after he’d rescued her from dancing the whole length of the Serpentine alone. “Go on,” she urged. “Go and find her.”

“I’ve found who I’m looking for,” he said. “I may not know your name, but I know you. And I have a secret, too.”

“Don’t tell me. You’re not really a horse?” She was looking up at him; his voice had struck her as familiar, but the familiarity was distant and vague, like something she’d dreamt. She tried to see through his mask but he was too tall; at the angle of her sight, all she could make out through the eye apertures was shadow.

“It’s true,” he confessed. “I am not really a horse.”

“And what are you?” She was really wondering now—who was he? Someone she knew? Masks made for mischief, and many a sly game was played on the Warlord’s birthday, but she didn’t think anyone would be playing games with her tonight.

His answer was swallowed by an upsurge of piping as they drew near the last musicians along the route. Trills like bird calls, a twanging lute, the throat-deep ululation of singers, and beneath it all, like a heartbeat under skin, the cadence of drums carrying the urgency to dance. Bodies were close on all sides, the stranger’s closest of all. A swell in the crowd pressed him against Madrigal and she felt the mass and breadth of his shoulders through his cloak.

And heat.

She was conscious of her bareness and sugar glitter, and, plainly, her own rushing heartbeat, her own rising heat.

She flushed and stepped away, or tried to, but was shoved back into him. His scent was warm and full: spice and salt, the pungent leather of his mask, and something rich and deep that she couldn’t identify but that made her want to lean into him, close her eyes, and breathe. He kept an arm around her, pushed back against the crush and kept her from being jostled, and there was nowhere to go but onward with the crowd as it funneled into the agora. They were in the funnel, and there was no turning back.

The stranger was behind her, his voice low. “I came here to find you,” he said. “I came to thank you.”

“Thank me? For what?” She couldn’t turn. A centaur flank hemmed her in on one side, a Naja coil on the other. She thought she caught a glimpse of Chiro in the whirl. She could see the agora now—straight ahead, framed by the armory and the war college. The lanterns overhead were like constellations, their flicker blotting out the real stars, and the moons, too. It crossed Madrigal’s mind to wonder if Nitid—curious, peering Nitid—could see in.

Something is going to happen.

“I came to thank you,” said the stranger, close to her ear, “for saving my life.”

Madrigal had saved lives. She had crept in darkness over fields of the fallen, slipped through seraphim patrols to glean souls that would otherwise be lost to evanescence. She had led a strike on an angel position that had her comrades trapped in a gully, and bought them time to retreat. She had shot an angel’s arrow out of the sky as it made its deadly glide toward a comrade. She had saved lives. But all those memories passed through her consciousness in the space of a finger snap, leaving only one.

Bullfinch. Mist. Enemy.

“I took your recommendation,” he said. “I lived.”

Instantly, it was as if her veins were conducting fire. She whipped around. His face was only inches from her own, his head tilted down so that now she could see into his mask.

His eyes blazed like flames.

She whispered, “You.”