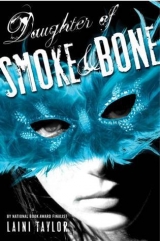

Текст книги "Daughter of Smoke & Bone"

Автор книги: Лэйни Тейлор

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Once upon a time,

an angel lay dying in the mist.

And a devil knelt over him and smiled

.

37

37

D REAM -L OST

Akiva was helpless to keep his blood in his body. It pulsed up under his fingers and escaped, riding the tide of his heartbeat out in hot spurts. He couldn’t stop the bleeding. The wound was a mauling, and clutching at it was a little like gathering a fistful of meat scraps to fling to a dog.

He was going to die.

Around him, the world had lost its horizons. Sea mist choked Bullfinch beach, and Akiva heard waves breaking but could see only as far as the nearest corpses: gray hummocks obscured by the fog. They might have been chimaera or seraphim—except for the nearest one, he couldn’t tell. That one lay only a few yards away, with his own sword embedded in it. The beast had been part hyena, part lizard, a monstrosity, and it had raked him open from collarbone to biceps, rending his mail as easily as cloth. It had clung to him, its teeth meeting through the flesh of his shoulder, even after he’d skewered it through its barrel chest. He’d twisted his blade, thrust deeper, twisted again. The beast had screamed deep in its throat, but didn’t let him go until it died.

Now, as Akiva lay waiting to die, the post-battle silence was split by a roar. He stiffened and clasped his wound tighter. Later, he would wonder why he’d done that. He should have let go, tried to die before they could reach him.

The enemy was stalking the field, killing the wounded. They had taken the day, driven the seraphim back to the fortifications at Morwen Bay, and they had no interest in prisoners. Akiva should have hurried his dying, slipped away in the calm of blood loss, like falling asleep. The enemy would be far less kind.

What made him wait? The hope of killing one more chimaera? But if that was it, why didn’t he try to drag himself over to retrieve his sword? He just lay there, holding his wound, living those extra few minutes for no reason that he could fathom.

And then he saw her.

She was just a silhouette at first. Vast bat wings, long ridged gazelle horns as sharp as pikes—the bestial parts of the enemy. Black loathing filled Akiva and he watched her pause beside first one corpse and then the next. She came to the body of the hyena-lizard and stood there a long moment—what was she doing? Death rites?

She turned and prowled toward Akiva.

She came clearer with every step. She was slender, her legs long—lean human thighs that gave way, below the knee, to the sleek taper of gazelle’s legs, the fine cloven hooves making her seem to balance on pins. Her wings were folded, her gait both graceful and tense with suppressed power. In one hand she held a crescent-moon blade; another just like it was sheathed at her thigh. With the other hand she raised a long staff that was not a weapon. It was curved like a shepherd’s crook, with something silver—a lantern?—suspended from the end.

No, not a lantern. It gave off not light, but smoke.

A few steps, hooves sinking into the sand, then the mist revealed her face to him, and his to her. She stopped abruptly when she saw he was alive. He braced for a snarl, a sudden lunge, and new pain as he was gutted by her blade, but the chimaera girl didn’t move. For a long moment they just looked at each other. She cocked her head to one side, a quizzical, birdlike gesture that spoke not of savagery, but curiosity. There was no snarl on her lips. Her face was solemn.

Unaccountably, she was beautiful.

She took a step closer. He watched her face as she drew nearer. His gaze slipped down her long neck to the ridges of her collarbones. She was finely made, elegant and spare. Her hair was short as swan’s down, soft and dark and close as a cap, so the architecture of her face was unobscured; perfect. Black greasepaint made a mask around her eyes, which Akiva could see were large—brown and bright, vivid and sorrowful.

He knew the sorrow was for her fallen comrades and not for him, but he still found himself transfixed by the compassion in her gaze. It made him think that perhaps he had never really looked at a chimaera before. He saw slaves often enough, but they kept their eyes on the ground, and warriors like this he only ever met while dodging a killing blow or dealing one, half-blind with the blood rage of battle. If he ignored the fact of her bloodied blade and her closely fitted black armor, her devilish wings and horns, if he focused just on her face—so unexpectedly lovely—she looked like a girl, a girl who had found a young man dying on the beach.

For a moment, that’s what he was. Not a soldier, not anyone’s enemy, and the death that was upon him seemed meaningless. That they lived as they did, angels and monsters locked in a volley of killing and dying, dying and killing, seemed an arbitrary choice.

As if they might just as well choose not to kill and die.

But no. That was all there was between them. And this girl was here for the same reason he was: to slay the enemy. And that meant him.

Why, then, didn’t she do it?

She knelt at his side, doing nothing to protect herself from any sudden move he might make. He remembered the knife at his hip. It was small, nothing like her own fantastical double-crescent, but it could kill her. In one motion he could embed it in the soft curve of her throat. Her perfect throat.

He made no move.

He was dream-lost by then. Blood-lost. Gazing up at the face above him, he was beyond wondering whether this was real. It could be a dying dream, or she could be a reaper sent from the next life to cull his soul. The silver censer hung on its crook, exhaling a fume of smoke that was both herbal and sulfurous, and as its scent wafted down to him, Akiva felt a tug, a lure. Dizzy, he thought he wouldn’t mind following this messenger into the next realm.

He imagined her guiding him by the hand, and with that serene image cradled in his mind, he let go of his wound to reach for her fingers, caught them in his, which were slippery with blood.

Her eyes went wide and she snatched her hand away.

He’d startled her; he hadn’t meant to. “I’ll go with you,” he said, speaking in Chimaera, which he knew enough of to give orders to slaves. It was a rough tongue, a cobbling together of many tribal dialects that the Empire had brought under one roof, and which had been melded over time into a common language. He could scarcely hear his own voice, but she made out his words well enough.

She glanced at her censer, then back at him. “That’s not for you,” she said, taking it away and planting it in the mud where the breeze would tease the smoke downwind. “I don’t think you want to go where I’m going.” Even under the animal inflections of the language, her voice was as pretty as a song.

“Death,” said Akiva. His life was leaving him fast now that he no longer held his wound. His eyes just wanted to drift closed. “I’m ready.”

“Well, I’m not. I hear it’s dull, being dead.”

She said it lightly, amused, and he peered up at her. Had she just made a joke? She smiled.

Smiled.

He did, too. Amazed, he felt it happening, as if her smile had triggered a reflex in him. “Dull sounds nice,” he said, letting his eyes flutter closed. “Maybe I can catch up on my reading.”

She muffled a laugh, and Akiva, drifting, began to believe that he was dead. It would be less strange than if this were really happening. He could no longer feel his torn shoulder, so he didn’t realize that she was touching him until he felt a tight pain. He gasped as his eyes flew open. Had she stabbed him after all?

No. She had winched a tourniquet above his wound. That was the pain. He looked wonderingly up at her.

She said, “I recommend living.”

“I’ll try.”

Then, voices nearby, guttural. Chimaera. The girl froze, held a finger to her lips and breathed, “Shhh.”

One last look passed between them. The fog diffused the sun behind her, limning her horns and wings in radiance. Her shorn hair was velvet nap—it looked as soft as a foal’s throat—and her horns were oiled, gleaming like polished jet. In spite of her wicked greasepaint mask, her face was sweet, her smile sweet. Akiva was unfamiliar with sweetness; it pierced him in the center of his chest, in some deep place that had never given any hint before that it was a locus of feeling. It was as new and strange as if an eye had suddenly peeled itself open in the back of his head, seeing in a new dimension.

He wanted to touch her face but held back because his hand was covered with blood, and besides, even his uninjured arm felt so heavy he didn’t think he could lift it.

But she had the same impulse. She reached out, hesitated, then trailed the tips of cool, cool fingers down his fever-hot brow, over the ridge of his cheek to rest against the soft pulse point of his throat. She left them there a moment, as if reassuring herself that life still beat in his blood.

Did she feel how his pulse quickened at her touch?

And then, in a bound, she was up and gone. Those long legs with their gazelle hooves and lean long muscles propelled her away through the mist in fluid leaps that were nearly flight, her wings half-folded and held aloft like kites so her descent from each leap was a balletic drift. At a distance, Akiva saw her shadow-shape meet others in the fog—hulking beasts with none of her lithe grace. Voices carried toward him, full of snarls, and hers in their midst, calming. He trusted that she would lead them away from him, and she did.

Akiva lived, and was changed.

“Who tied this tourniquet?” Liraz asked him later, when she found him and got him to safety. He said he didn’t know.

He felt as if his life to that point had been spent wandering in a labyrinth, and on the battlefield at Bullfinch he’d finally found its center. His own center—that place where feeling had pulsed up from numbness. He’d never even suspected the place existed until the enemy knelt beside him and saved his life. He remembered her with the softness of a dream, but she was not a dream.

She was real, and she existed in the world. Like animal eyes shining from a nighttime wood, she was out there, a brief shimmer of radiance in the all-encompassing dark.

She was out there.

38

38

U NGODLY

After Bullfinch, Madrigal’s existence—it would be two years before he learned her name—had called to Akiva like a voice adrift in a great silence. As he lay near death in the battle encampment at Morwen Bay, he dreamed again and again that the enemy girl was kneeling over him, smiling. Each time he woke to her absence, to see instead the faces of his kith and kin, they seemed less real than this eidolon who haunted him. Even as Liraz fended off the doctor who wanted to amputate his arm, his mind was called back to the mist-shrouded beach at Bullfinch, to brown eyes and oiled horns and that shock of sweetness.

He had trained to withstand the devil marks, but not this. Against this, he found he had no defense.

Of course, he told no one.

Hazael came to his bedside with his kit of tattoo tools to mark Akiva’s hands with his Bullfinch kills. “How many?” he asked, heating up his knife blade to sterilize it.

Akiva had slain six chimaera at Bullfinch, including the hyena monstrosity that had taken him down. Six new ticks would fill out his right hand, which, thanks to Liraz, was still attached to his body. The arm lay useless at his side. Severed nerves and muscles had been reattached; he wouldn’t know for some time if it would ever function again.

When Hazael picked up the lifeless hand, knife at the ready, all Akiva could think of was the enemy girl, and how she might end up a black mark on some seraph’s knuckle. The thought was unendurable. With his good hand, he wrested his arm from Hazael and was immediately swamped with pain. “None,” he gasped. “I didn’t kill any.”

Hazael squinted. “You did. I was with you against that phalanx of bull centaurs.”

But Akiva wouldn’t take the marks, and Hazael went away.

Thus, had begun the secret that, over the years, grew into a rift between them, and that, in the skies of the human world, threatened to tear them apart forever.

When Karou exploded off the bridge, Liraz followed, and Akiva surged up to block her. Their blades clashed. He crossed his two swords close to the hilt and put his strength behind them with a steady pressure that forced his sister back. He kept Hazael in sight, afraid he would pursue Karou, but his brother was still standing on the bridge, staring up at the unimaginable sight of Akiva and Liraz with swords crossed.

Liraz’s arms trembled with the effort at holding her ground—her air—and her wings worked at furious backbeats. Her face was livid, clench-jawed and lurid with striving, and her eyes were so wide that her irises were spots in staring white orbs.

With a banshee wail she threw Akiva off, swung her freed sword in a cyclone around her head, and brought it hacking down.

He blocked it. Its force jarred his bones. She wasn’t holding back. The ferocity of her attack shocked him—would she really try to kill him? She hacked again, and he blocked, and Hazael finally came unfrozen and leapt toward them.

“Stop,” he cried, aghast. He started to dart in but had to dodge when Liraz swung wild. Akiva parried the blow, knocking her off balance, and she whirled around before fumbling to a hover. She gave him a look that glittered with malice, and instead of coming at him again, she surged upward. Her wings gave off a fireball burst that brought a collective gasp from the onlookers, and then she was speeding in the direction Karou had gone.

The sky gave no hint of Karou, but Akiva didn’t doubt that Liraz could track her. He sped after her. Precipitously, the rooftops receded, and humanity with them. There was just the rushing air, the flare of wings, and—he caught up to his sister and grabbed her arm—strife.

She spun on him again, slashing, and their swords rang out, again and again. As in Prague, when Karou had attacked him, Akiva only parried, dodged, and did not return attack.

“Stop!” barked Hazael again, coming up on Akiva and giving him a hard shove that put distance between him and Liraz. They were high above the city now, in airy silence echoing with the ring of steel. “What are you doing?” Hazael demanded in a tone of disbelief. “You two, fighting—”

“I’m not,” said Akiva, backing away. “I won’t.”

“Why not?” hissed Liraz. “You might as well slit my throat as stab me in the back.”

“Liraz, I don’t want to hurt you—”

She laughed. “You don’t want to, but you will if you have to? Is that what you’re saying?”

Was it? What would he do to protect Karou? He couldn’t harm his sister or brother; he could never live with that. But he couldn’t let them hurt Karou, either. How could these be his only two choices?

“Just… forget her,” he said. “Please. Just let her go.”

The thick emotion in his voice made Liraz’s eyes narrow with scorn. Looking at her, Akiva thought that he might as well appeal to a sword as to her. And wasn’t that what they were all three bred to be, and all the emperor’s other bastards, too? Weapons forged in flesh. Unthinking instruments of age-old enmity.

He couldn’t accept that. They were more than that, all of them. He hoped. He took a risk. He sheathed his swords. Her eyes like slashes, Liraz watched in silence.

“At Bullfinch,” he said, “you asked who tied my tourniquet.”

She waited. Hazael, too.

Akiva thought of Madrigal, remembered the feel of her skin, the surprising smoothness of her leathern wings, and the light of her laughter—so like Karou’s laughter—and he recalled what Karou had said to him that morning: If he’d ever known any chimaera, he couldn’t dismiss them as monsters.

But he had, both. He had known and loved Madrigal, and still he had become what he had become—the dead-eyed husk that had almost slain Karou on impulse. Grief had grown its ugly blooms in him: hate, vengeance, blindness. The person he was now, Madrigal would have regretted ever saving his life. But in Karou, he had another chance—for peace, that is. Not for happiness, not for him. It was too late for him.

For others, maybe there could still be salvation.

“It was a chimaera,” he told his sister and brother. He gulped a breath of air, knowing that this would sound ungodly to them. They had been taught from the cradle that chimaera were vile, crawling things, devils, animals. But Madrigal… she had managed to unchain him in an instant from his bigotry, and it was time he tried to do the same. “A chimaera saved my life,” he said. “And I fell in love with her.”

39

39

B LOOD W ILL O UT

After Bullfinch, everything changed for Akiva. When he sent Hazael and his tattoo kit away, an idea took hold: When he saw the chimaera girl again, he would be able to tell her that he had not used the life she had given him to kill any more of her kindred.

That he would ever see her again was extravagantly unlikely, but the notion took up residence in his mind—a darting, fugitive thing he couldn’t seem to chase away—and he became accustomed to its lurking presence. He grew comfortable with it, and the thing morphed from a wild notion into a hope—a sustaining hope, and the one that would change the course of his life: to see the girl again, and thank her. That was all, just thank her. When he imagined the moment, his mind went no further.

It was enough to keep him going.

He wasn’t long in Morwen Bay after the battle. The battle surgeons sent him back to Astrae to see what the healers there could do for him.

Astrae.

Until the Massacre a millennium past, the seraphim had ruled the Empire from Astrae. For three hundred years it had been, by all accounts, the light of the world, the most beautiful city ever built. Palaces, arcades, fountains, all pearl marble quarried in Evorrain, broad boulevards paved in quartz, overreached by the honey-scented boughs of gilead. It perched above its harbor on striated cliffs, with the emerald Mirea coast as far as the eye could see. Like in Prague, spires pointed to the heavens, one for each of the godstars—the godstars that had ordained seraphim as guardians of the land and all its creatures.

The godstars that had looked on as it all fell into chaos.

At three hundred years, Akiva thought, the citizens of Astrae must have felt that it had always been and would always be. Now, ten centuries later, its golden age seemed like the long-ago blink of some dead god’s eye, and little remained of the original city. The enemy had razed it: toppled the towers, burned everything that would catch fire. They would have torn the very stars from the heavens if they could. Such savagery had no precedent in history. At the end of the first day, the magi lay dead, even their youngest apprentices, and their library was swallowed by fire, with every magical text in all of Eretz.

Strategically, it made sense. Seraphim had come to rely so heavily on magic that in the aftermath of the Massacre, with not a single magus left alive, they were very nearly helpless. Any angels who hadn’t escaped Astrae were sacrificed on an altar by the light of the full moon, and the seraph emperor, ancestor of Akiva’s father, was among them. So many angels had bled out their lives on that altar stone that their blood rolled down the temple steps like monsoon rains and drowned small creatures in the streets.

The beasts held Astrae for centuries, until Joram—Akiva’s father—waged an all-out campaign early in his reign and won back all the territory up to the Adelphas Mountains. He had consolidated power and begun to rebuild the Empire, with its heart where, as he said, it belonged: in Astrae.

Where Joram had not made much headway was with magic. With the library burned and the magi dead, the seraphim had been knocked back to the most basic of manipulations, and in all the intervening centuries, they hadn’t progressed much beyond them.

Akiva had never given much thought to magic. He was a soldier; his education was limited. He presumed it a mystery for other, brighter minds. But his sojourn in Astrae changed that. He had the time to discover that his mind, soldier’s though it was, burned brighter than most, and that he possessed something the would-be magi of Astrae did not. In truth, he had two things they didn’t. He had the blood for it, though it took a malicious comment from his father for him to know it. And he had the most critical thing, the crux.

He had pain.

The pain in his shoulder was a constant, and so was his eidolon, the enemy girl, and the two were linked. When his shoulder burned, coming slowly back to life, he couldn’t help but think of her fine hands on it, winching the tourniquet that had saved him.

The healers of Astrae spurned the drugs of the battle surgeons, which didn’t help matters, and they made him use his arm. A slave—chimaera—was employed for the purpose of stretching it to keep the muscles supple, and Akiva was ordered onto the practice field to work his left arm in swordsmanship, in case the right never fully recovered. Against expectation, it did, though the pain did not diminish, and within a few months he was a more formidable swordsman than he had been before. He visited the palace armorer about a set of matched blades, and soon he reigned on the practice field. Fighting two-handed, he drew crowds to the morning bouts, including the emperor himself.

“One of mine?” asked Joram, appraising him.

Akiva had never been in his father’s immediate presence. Joram’s bastards were legion; he couldn’t be expected to know them all. “Yes, my Lord,” said Akiva with bowed head. His shoulders still heaved from the exertion of sparring, his right sending out the flares of agony that were just a part of living now.

“Look at me,” ordered the emperor.

Akiva did, and saw nothing of himself in the seraph before him. Hazael and Liraz, yes. Their blue eyes came straight from Joram, as did the set of their features. The emperor was fair, his golden hair going to gray, and though broad, he was of modest height and had to look up at Akiva.

His look was sharp. He said, “I remember your mother.”

Akiva blinked. He hadn’t been expecting that.

“It’s the eyes,” said the emperor. “They’re unforgettable, aren’t they?”

It was one of the few things Akiva did remember about his mother. The rest of her face was a blur, and he’d never even known her name, but he knew that he had her eyes. Joram seemed to be waiting for him to answer, so he acknowledged, “I remember,” and felt a tug of loss, as if, by admitting it, he was handing over the one thing he had of her.

“Terrible what happened to her,” said Joram.

Akiva went still. He’d had no knowledge of his mother after he was taken from her, as surely the emperor knew. Joram was baiting him, wanting him to ask, What? What happened to her? But Akiva didn’t ask, only clenched his teeth, and Joram, smiling knives, said, “But what can you expect, really, of Stelians? Savage tribe. Almost as bad as the beasts. Watch that the blood doesn’t out, soldier.”

And he walked away, leaving Akiva with the burn of his shoulder and a new urgency to know what he had never cared about before: What blood?

Could his mother have been Stelian? It made no sense that Joram would have had a Stelian concubine; he had no diplomatic relations with the “savage tribe” of the Far Isles, renegade seraphim who would never have given their women as tribute. How, then, had she come to be there?

The Stelians were known for two things. The first was their fierce independence—they were not part of the Empire, having steadfastly refused, over the centuries, to come into the fold with their seraph kindred.

The second was their sympathy with magic. It was believed, in the deep murk of history, that the first magi had been Stelian, and they were rumored still to practice a rarified level of magic unknown in the rest of Eretz. Joram hated them because he could neither conquer nor infiltrate them, at least not while needing to focus his forces on the Chimaera War. There was no doubt, though, in the gossip that swirled through the capital, of where he would set his sights once the beasts were broken.

As for what had happened to his mother, Akiva never found out. The harem was a closed world, and he couldn’t even confirm that there had ever been a Stelian concubine, let alone what had become of her. But for himself, something grew out of his encounter with his father: a sympathy with those strangers of his blood, and a curiosity about magic.

He was in Astrae for more than a year, and besides physical therapy, sparring, and some hours each day in the training camp drilling young soldiers in arms, his time was his own. After that day, he made use of it. He knew about the pain tithe, and thanks to his wound, he now had a constant reservoir of pain to draw on. Observing the magi—to whom he, a brute soldier, was as good as invisible—he learned the fundamental manipulations, starting with summoning. He practiced on bat-crows and hummingbird-moths in the dark of night, directing their flight, lining them up in Vs like winter geese, calling them down to perch on his shoulders, or in his cupped hands.

It was easy; he kept going. He quickly came up against the boundary of the known, which wasn’t saying much—what passed for magic in this age was little more than parlor tricks, illusions. And he never fooled himself that he was a magus, or anywhere close, but he was inventive, and unlike the courtly fops who called themselves magi, he didn’t have to flog or burn or cut himself to dredge up power—he had it, low and constant. But the real reason he surpassed them was neither his pain nor his inventiveness. It was his motivation.

The idea that had grown from a wild thing into a hope—to see the chimaera girl again—had become a plan.

It had two parts. Only the first was magical: to perfect a glamour that could conceal his wings. There was a manipulation for camouflage, but it was rudimentary, only a kind of “skip” in space that could trick the eye—at a distance—into overlooking the object in question. Invisibility it was not. If he hoped to pass in disguise among the enemy—which was exactly what he hoped—he would have to do better than that.

So he worked at it. It took months. He learned to go into his pain, like it was a place. From within it, things looked different—sharp-edged—and felt and sounded different, too, tinny and cool. Pain was like a lens that honed everything, his senses and instincts, and it was there, through relentless trial and repetition, that he did it. He achieved invisibility. It was a triumph that would have garnered him fame and the emperor’s highest honors, and it gave him a cold satisfaction to keep it to himself.

Blood will out, he thought. Father.

The other part of his plan was language. To master Chimaera, he perched on the roof of the slave barracks and listened to the stories they told by the light of their stinking dungfire. Their tales were unexpectedly rich and beautiful, and, listening, he couldn’t help imagining his chimaera girl sitting at a battle campfire somewhere telling the same stories.

His. He caught himself thinking of her as his, and it didn’t even seem strange.

By the time he was sent back to his regiment at Morwen Bay, he could have used a little more time to perfect his Chimaera accent, but he thought he was basically ready for what came next, in all its bright and shining madness.