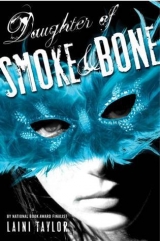

Текст книги "Daughter of Smoke & Bone"

Автор книги: Лэйни Тейлор

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

5

5

E LSEWHERE

Kishmish took to the sky and was gone in a flutter. Karou watched, wishing she could follow. What magnitude of wish, she wondered, would it take to endow her with flight?

One far more powerful than she’d ever have access to.

Brimstone wasn’t stingy with scuppies. He let her refresh her necklace as often as she liked from his chipped teacups full of beads, and he paid her in bronze shings for the errands she ran for him. A shing was the next denomination of wish, and it could do more than a scuppy—Svetla’s caterpillar eyebrows were a case in point, as were Karou’s tattoo removal and her blue hair—but she had never gotten her hands on a wish that could work any real magic. She never would, either, unless she earned it, and she knew too well how humans earned wishes. Chiefly: hunting, graverobbing, and murder.

Oh, and there was one other way: a particular form of self-mutilation involving pliers and a deep commitment.

It wasn’t like in the storybooks. No witches lurked at crossroads disguised as crones, waiting to reward travelers who shared their bread. Genies didn’t burst from lamps, and talking fish didn’t bargain for their lives. In all the world, there was only one place humans could get wishes: Brimstone’s shop. And there was only one currency he accepted. It wasn’t gold, or riddles, or kindness, or any other fairy-tale nonsense, and no, it wasn’t souls, either. It was weirder than any of that.

It was teeth.

Karou crossed the Charles Bridge and took the tram north to the Jewish Quarter, a medieval ghetto that had given way to a dense concentration of Art Nouveau apartment buildings as pretty as cakes. Her destination was the service entrance in the rear of one of them. The plain metal door didn’t look like anything special, and in and of itself, it wasn’t. If you opened it from without, it revealed only a mildewed laundry room. But Karou didn’t open it. She knocked and waited, because when the door was opened from within, it had the potential to lead someplace quite different.

It swung open and there was Issa, looking just as she did in Karou’s sketchbooks, like a snake goddess in some ancient temple. Her serpent coils were withdrawn into the shadows of a small vestibule. “Blessings, darling.”

“Blessings,” Karou returned fondly, kissing her cheek. “Did Kishmish make it back?”

“He did,” said Issa, “and he felt like an icicle on my shoulder. Come in now. It’s freezing in your city.” She was guardian of the threshold, and she ushered Karou inside, closing the door behind her so the two of them were alone in a space no bigger than a closet. The outer door of the vestibule had to seal completely before the inner one could be opened, in the manner of safety doors at aviaries that prevent birds from escaping. Only, in this case, it wasn’t for birds.

“How was your day, sweet girl?” Issa had some half dozen snakes on her person—wound around her arms, roaming through her hair, and one encircling her slim waist like a belly dancer’s chain. Anyone seeking entry would have to submit to wearing one around the neck before the inner door would unseal—anyone but Karou, that is. She was the only human who entered the shop uncollared. She was trusted. After all, she’d grown up in this place.

“It’s been a day,” Karou sighed. “You won’t believe what Kaz did. He showed up to be the model in my drawing class.”

Issa had not met Kaz, of course, but she knew him the same way Kaz knew her: from Karou’s sketchbooks. The difference was that while Kaz thought Issa and her perfect breasts were an erotic figment of Karou’s imagination, Issa knew Kaz was real.

She and Twiga and Yasri were as hooked on Karou’s sketchbooks as her human friends were, but for the opposite reason. They liked to see the normal things: tourists huddled under umbrellas, chickens on balconies, children playing in the park. And Issa especially was fascinated by the nudes. To her, the human form—plain as it was, and not spliced together with other species—was a missed opportunity. She was always scrutinizing Karou and making such pronouncements as, “I think antlers would suit you, sweet girl,” or “You’d make a lovely serpent,” in just the way a human might suggest a new hairstyle or shade of lipstick.

Now, Issa’s eyes lit up with ferocity. “You mean he came to your school? The scandalous rodent-loaf! Did you draw him? Show me.” Outraged or not, she wouldn’t miss an opportunity to see Kaz naked.

Karou pulled out her pad and flipped it open.

“You scribbled out the best part,” Issa accused.

“Trust me, it’s not that great.”

Issa giggled into her hand as the shop door creaked open to admit them, and Karou stepped across the threshold. As always, she felt the slightest wave of nausea at the transition.

She was no longer in Prague.

Even though she had lived in Brimstone’s shop, she still didn’t understand where it was, only that you could enter through doorways all over the world and end up right here. As a child she used to ask Brimstone where exactly “here” was, only to be told brusquely, “Elsewhere.”

Brimstone was not a fan of questions.

Wherever it was, the shop was a windowless clutter of shelves that looked like some kind of tooth fairy’s dumping ground—if, that is, the tooth fairy trafficked in all species. Viper fangs, canines, grooved elephant molars, overgrown orange incisors from exotic jungle rodents—they were all collected in bins and apothecary chests, strung in garlands that draped from hooks, and sealed in hundreds of jars you could shake like maracas.

The ceiling was vaulted like a crypt’s, and small things scurried in the shadows, their tiny claws scritch-scritching on stone. Like Kishmish, these were creatures of disparate parts: scorpion-mice, gecko-crabs, beetle-rats. In the damp around the drains were snails with the heads of bullfrogs, and overhead, the ubiquitous moth-winged hummingbirds hurled themselves at lanterns, setting them swaying with the creak of copper chains.

In the corner, Twiga was bent over his work, his ungainly long neck bowed like a horseshoe as he cleaned teeth and banded them with gold to be strung onto catgut. A clatter came from the kitchen nook that was Yasri’s domain.

And off to the left, behind a huge oak desk, was Brimstone himself. Kishmish was perched in his usual place on his master’s right horn, and spread out on the desk were trays of teeth and small chests of gems. Brimstone was stringing them into a necklace and did not look up. “Karou,” he said. “I believe I wrote ‘errand requiring immediate attention.’ ”

“Which is exactly why I came immediately.”

“It’s been”—he consulted his pocket watch—“forty minutes.”

“I was across town. If you want me to travel faster, give me wings, and I’ll race Kishmish back. Or just give me a gavriel, and I’ll wish for flight myself.”

A gavriel was the second most powerful wish, certainly sufficient to grant the power of flight. Still bent over his work, Brimstone replied, “I think a flying girl would not go unnoticed in your city.”

“Easily solved,” said Karou. “Give me two gavriels, and I’ll wish for invisibility, too.”

Brimstone looked up. His eyes were those of a crocodile, luteous gold with vertical slit pupils, and they were not amused. He would not, Karou knew, give her any gavriels. She didn’t ask out of hope, but because his complaint was so unfair. Hadn’t she come running as soon as he’d called?

“I could trust you with gavriels, could I?” he asked.

“Of course you could. What kind of question is that?”

She felt his appraisal, as if he were mentally reviewing every wish she’d ever made.

Blue hair: frivolous.

Erasing pimples: vain.

Wishing off the light switch so she didn’t have to get out of bed: lazy.

He said, “Your necklace is looking quite short. Have you had a busy day?”

Her hand flew to cover it. Too late. “Why do you have to notice everything?” No doubt the old devil somehow knew exactly what she’d used these scuppies for and was adding it to his mental list:

Making ex-boyfriend’s cranny itch: vindictive.

“Such pettiness is beneath you, Karou.”

“He deserved it,” she replied, forgetting her earlier shame. Like Zuzana had said, bad behavior should be punished. She added, “Besides, it’s not like you ask your traders what they’re going to use their wishes for, and I’m sure they do a hell of a lot worse than make people itch.”

“I expect you to be better than them,” Brimstone said simply.

“Are you suggesting that I’m not?”

The tooth-traders who came to the shop were, with few exceptions, about the worst specimens humanity had to offer. Though Brimstone did have a small coterie of longtime associates who did not turn Karou’s stomach—such as the retired diamond dealer who had on a number of occasions posed as her grandmother to enroll her in schools—mostly they were a stinking, soul-dead lot with crescents of gore under their fingernails. They killed and maimed. They carried pliers in their pockets for extracting the teeth of the dead—and sometimes the living. Karou loathed them, and she was certainly better than them.

Brimstone said, “Prove that you are, by using wishes for good.”

Nettled, she asked, “Who are you to talk about good, anyway?” She gestured to the necklace clutched in his huge clawed hands. Crocodile teeth—those would be from the Somali. Also wolf fangs, horse molars, and hematite beads. “I wonder how many animals died in the world today because of you. Not to mention people.”

She heard Issa suck in a surprised breath, and she knew she should shut up, but her mouth kept moving. “No, really. You do business with killers, and you don’t even have to see the corpses they leave behind. You lurk in here like a troll—”

“Karou,” Brimstone said.

“But I’ve seen them, piles of dead creatures with bloody mouths. Those girls with their bloody mouths; I’ll never forget as long as I live. What’s it all for? What do you do with these teeth? If you would just tell me, maybe I could understand. There must be a reason—”

“Karou,” Brimstone said again. He did not say “shut up.” He didn’t have to. His voice conveyed it clearly enough, on top of which he rose suddenly from his chair.

Karou shut up.

Sometimes, maybe most of the time, she forgot to see Brimstone. He was so familiar that when she looked at him she saw not a beast but the creature who, for reasons unknown, had raised her from a baby, and not without tenderness. But he could still strike her speechless at times, such as when he used that tone of voice. It slithered like a hiss to the core of her consciousness and opened her eyes to the full, fearsome truth of him.

Brimstone was a monster.

If he and Issa, Twiga, and Yasri were to stray from the shop, that’s what humans would call them: monsters. Demons, maybe, or devils. They called themselves chimaera.

Brimstone’s arms and massive torso were the only human parts of him, though the tough flesh that covered them was more hide than skin. His square pectorals were riven with ancient scar tissue, one nipple entirely obliterated by it, and his shoulders and back were etched in more scars: a network of puckered white cross-hatchings. Below the waist he became elsething. His haunches, covered in faded, off-gold fur, rippled with leonine muscle, but instead of the padded paws of a lion, they tapered to wicked, clawed feet that could have been either raptor or lizard—or perhaps, Karou fancied, dragon.

And then there was his head. Roughly that of a ram, it wasn’t furred, but fleshed in the same tough brown hide as the rest of him. It gave way to scales around his flat ovine nose and reptilian eyes, and giant, yellowed ram horns spiraled on either side of his face.

He wore a set of jeweler’s lenses on a chain, and their dark gold rims were the only ornament on his person, if you didn’t count the other thing he wore around his neck, which had no sparkle to catch the eye. It was just an old wishbone, sitting in the hollow of his throat. Karou didn’t know why he wore it, only that she was forbidden to touch it, which, of course, had always made her long to do so. When she was a baby and he used to rock her on his knee, she would make little lightning grabs for it, but Brimstone was always faster. Karou had never succeeded in laying so much as a fingertip to it.

Now that she was grown she showed more decorum, but she still sometimes found herself itching to reach for the thing. Not now, though. Cowed by Brimstone’s abrupt rising, she felt her rebelliousness subside. Taking a step back, she asked in a small voice, “So, um, what about this urgent errand? Where do you need me to go?”

He tossed her a case filled with colorful banknotes that turned out to be euros. A lot of euros.

“Paris,” said Brimstone. “Have fun.”

6

6

T HE A NGEL OF E XTINCTION

Fun?

“Oh, yes,” Karou muttered to herself later that night as she dragged three hundred pounds of illegal elephant ivory down the steps of the Paris Metro. “This is just so much fun.”

When she’d left Brimstone’s shop, Issa had let her out through the same door by which she’d entered, but when she stepped onto the street she was not back in Prague. She was in Paris, just like that.

No matter how many times she went through the portal, the thrill never wore off. It opened onto dozens of cities, and Karou had been to them all, on errands like this one and sometimes for pleasure. Brimstone let her go out and draw anywhere in the world where there wasn’t a war, and when she had a craving for mangoes he opened the door to India, on the condition that she bring some back for him, too. She had even wheedled her way into shopping expeditions to exotic bazaars, and right here, to the Paris flea markets, to furnish her flat.

Wherever she went, when the door closed behind her, its connection to the shop was severed. Whatever magic was at work, it existed in that other place—Elsewhere, as she thought of it—and could not be conjured from this side. No one would ever force his way into the shop. One would only succeed in breaking through an earthly door that didn’t lead where he hoped to go.

Even Karou was dependent on the whim of Brimstone to admit her. Sometimes he didn’t, however much she knocked, though he had never yet stranded her on the far side of an errand, and she hoped he never would.

This errand turned out to be a black-market auction in a warehouse on the outskirts of Paris. Karou had attended several such, and they were always the same. Cash only, of course, and attended by sundry underworld types like exiled dictators and crime lords with pretensions to culture. The auction items were a mixed salad of stolen museum pieces—a Chagall drawing, the dried uvula of some beheaded saint, a matched set of tusks from a mature African bull elephant.

Yes. A matched set of tusks from a mature African bull elephant.

Karou sighed when she saw them. Brimstone hadn’t told her what she was after, only that she would know it when she saw it, and she did. Oh, and wouldn’t they be a delight to wrangle on public transportation?

Unlike the other bidders, she didn’t have a long black car waiting, or a pair of thug bodyguards to do her heavy lifting. She had only a string of scuppies and her charm, neither of which proved sufficient to persuade a cab driver to hang seven-foot-long elephant tusks out the back of his taxi. So, grumbling, Karou had to drag them six blocks to the nearest Metro station, down the stairs, and through the turnstile. They were wrapped in canvas and duct-taped, and when a street musician lowered his violin to inquire, “Hey lovely, what you got there?” she said, “Musicians who asked questions,” and kept on dragging.

It could have been worse, certainly, and often was. Brimstone sent her to some god-awful places in pursuit of teeth. After the incident in St. Petersburg, when she was recovering from being shot, she’d demanded, “Is my life really worth so little to you?”

As soon as the question was out of her mouth, she’d regretted it. If her life was worth so little to him, she didn’t want him to admit it. Brimstone had his faults, but he was all she had for a family, along with Issa and Twiga and Yasri. If she was just some kind of expendable slave girl, she didn’t want to know.

His answer had neither confirmed nor denied her fear. “Your life? You mean, your body? Your body is nothing but an envelope, Karou. Your soul is another matter, and is not, as far as I know, in any immediate danger.”

“An envelope?” She didn’t like to think of her body as an envelope—something others might be able to open up and rifle through, remove things from like so many clipped coupons.

“I assumed you felt the same way,” he’d said. “The way you scribble on it.”

Brimstone didn’t approve of her tattoos, which was funny, since he was responsible for her first, the eyes on her palms. At least Karou suspected he was, though she didn’t know for sure, since he was incapable of answering even the most basic questions.

“Whatever,” she’d said with a pained sigh. Really: pained. Getting shot hurt, no surprise there. Of course, she couldn’t argue that Brimstone shoved her unprepared into danger. He’d seen to it that she was trained from a young age in martial arts. She never mentioned it to her friends—it was not, her sensei had taught her early, a bragging matter—and they would have been surprised to learn that Karou’s gliding, straight-spined grace went hand in hand with deadly skill. Deadly or not, she’d had the misfortune to discover that karate went only so far against guns.

She’d healed quickly with the help of a pungent salve and, she suspected, magic, but her youthful fearlessness had been shaken, and she went on errands with more trepidation now.

Her train came, and she wrestled her burden through the doors, trying not to think too much about what was in it, or the magnificent life that had been ended somewhere in Africa, though probably not recently. These tusks were massive, and Karou happened to know that elephant tusks rarely grew so big anymore—poachers had seen to that. By killing all the biggest bulls, they’d altered the elephant gene pool. It was sickening, and here she was, part of that blood trade, hauling endangered species contraband on the freaking Paris Metro.

She shut the thought away in a dark room in her mind and stared out the window as the train sped through its black tunnels. She couldn’t let herself think about it. Whenever she did, her life felt gore-streaked and nasty.

Last semester, when she’d made her wings, she’d dubbed herself “the Angel of Extinction,” and it was entirely appropriate. The wings were made of real feathers she’d “borrowed” from Brimstone—hundreds of them, brought to him over the years by traders. She used to play with them when she was little, before she understood that birds had been killed for them, whole species driven extinct.

She had been innocent once, a little girl playing with feathers on the floor of a devil’s lair. She wasn’t innocent now, but she didn’t know what to do about it. This was her life: magic and shame and secrets and teeth and a deep, nagging hollow at the center of herself where something was most certainly missing.

Karou was plagued by the notion that she wasn’t whole. She didn’t know what this meant, but it was a lifelong feeling, a sensation akin to having forgotten something. She’d tried describing it to Issa once, when she was a girl. “It’s like you’re standing in the kitchen, and you know you went in there for a reason, but you can’t think of what that reason is, no matter what.”

“And that’s how you feel?” asked Issa, frowning.

“All the time.”

Issa had only drawn her close and stroked her hair—then its natural near-black—and said, unconvincingly, “I’m sure it’s nothing, lovely. Try not to worry.”

Right.

Well. Getting the tusks up the Metro steps at her destination was a lot harder than dragging them down had been, and by the top Karou was exhausted, sweating under her winter coat, and extremely peevish. The portal was a couple more blocks away, linked to the doorway of a synagogue’s small storage outbuilding, and when she finally reached it she found two Orthodox rabbis in deep conversation right in front of it.

“Perfect,” she muttered. She continued past them and leaned against an iron gate, just out of sight, to wait while they discussed some act of vandalism in mystified tones. At last they left, and Karou wrangled the tusks to the little door and knocked. As she always did while waiting at a portal in some back alley of the world, she imagined being stranded. Sometimes it took long minutes for Issa to open the door, and each and every time, Karou considered the possibility that it might not open. There was always a twinge of fear of being locked out, not just for the night, but forever. The scenario made her hyperaware of her powerlessness. If, some day, the door didn’t open, she would be alone.

The moment stretched, and Karou, leaning wearily against the doorframe, noticed something. She straightened. On the surface of the door was a large black handprint. That wouldn’t have been so very strange, except that it gave every appearance of having been burned into the wood. Burned, but in the perfect contours of a hand. This must be what the rabbis were talking about. She traced it with her fingertips, finding that it was actually scored into the wood, so that her own hand fit inside it, though dwarfed by it, and came away dusted with fine ash. She brushed off her fingers, puzzled.

What had made the print? A cleverly shaped brand? It sometimes happened that Brimstone’s traders left a mark by which to find portals on their next visit, but that was usually just a smear of paint or a knife-gouged X-marks-the-spot. This was a bit sophisticated for them.

The door creaked open, to Karou’s deep relief.

“Did everything go all right?” Issa asked.

Karou heaved the tusks into the vestibule, having to wedge them at an angle to fit them inside. “Sure.” She slumped against the wall. “I’d drag tusks across Paris every night if I could, it was such a treat.”