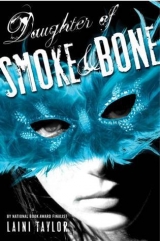

Текст книги "Daughter of Smoke & Bone"

Автор книги: Лэйни Тейлор

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

57

57

R EVENANT

“Akiva,” breathed Karou with the fullness of her self.

Mere seconds had passed since they had broken the wishbone, but in that space of time, years had come home to her. Seventeen years ago, Madrigal had ended. All that had happened since was another life, but it was hers, too. She was Karou, and she was Madrigal. She was human and chimaera.

She was revenant.

Within her, something was at work: a swift concrescence of memories, two consciousnesses that were really one, coming together like interlacing fingers.

She saw her hamsas and knew what Brimstone had done. In defiance of Thiago’s sentence of evanescence, he had somehow gleaned her soul. And because she could not have a life in her own world, he had given her one here, in secret. How had he extracted her memory from her soul? The life she had lived as Madrigal—he had taken it all and put it in the wishbone, and saved it for her.

It came to her what Izîl had said the last time she saw him, when he offered her baby teeth and she rejected them. “Once,” he’d said, and she hadn’t believed him. “Once he wanted some.”

She believed it now.

Revenants were made for battle; their bodies were always conjured fully grown, from mature teeth. But Brimstone had made her a baby, a human, named her hope and given her a whole life, far away from war and death. Sweet, deep, fond love filled her. He had given her a childhood, a world. Wishes. Art. And Issa and Yasri and Twiga, they had known and helped; hidden her. Loved her. She would see them soon, and she wouldn’t stand back from Brimstone as she always did, cowed by his gruffness and his monstrous physical presence. She would throw her arms around him and say, finally, thank you.

She looked up from her palms—from one wonder to another—and Akiva was before her. He still stood at the foot of the bed on which, just a moment earlier, they had fallen back together, all of him against all of her, and Karou understood that the aching allness rose from what she had shared with him in another body, another life. She had fallen in love with him twice. She loved him now with both loves, so overpowering it was almost unbearable. She beheld him through a prism of tears.

“You escaped,” she said. “You lived.”

She uncoiled from the bed, flashed toward him, threw herself against the remembered solidity of him, the heat.

A hesitation, then his arms came around her, tight. He didn’t speak, but held her against him and rocked back and forth. She felt him shake, weeping, his lips pressed to the crown of her head.

“You escaped,” she repeated, sobbing, but laughing now, too. “You’re alive.”

“I’m alive,” he whispered, choked. “You’re alive. I never knew. All these years, I never thought—”

“We’re alive,” Karou said, dazed. The wonder of it swelled within her, and she felt like their myth had come to life. They had a world; they were in it. This place that Brimstone had given her, it was half her home, and the other half lay waiting through a portal in the sky. They could have both, couldn’t they?

“I saw you die,” Akiva said, helpless. “Karou… Madrigal… My love.” His eyes, his expression. He looked as he had seventeen years ago, on his knees, forced to watch. He said again, “I saw you die.”

“I know.” She kissed him tenderly, remembering the scouring horror of his scream. “I remember it all.”

As did he.

The hooded executioner: a monster. The Wolf and the Warlord, looking on from their balcony, and the crowd, their stamping riot, their roars and bloodlust: monsters all, making a mockery of the dream of peace Akiva had nurtured since Bullfinch. Because one among them had touched his soul, he had believed them all worthy of that dream.

And there she stood in shackles—the one; his one—her wings in their pinion crimped cruelly out of shape, and the sham dream was gone. This was what they did to their own. His beautiful Madrigal, graceful even now.

He watched in helpless horror as she sank to her knees. Laid her head on the block. Impossible, screamed Akiva’s heart. This couldn’t happen. The will, the mystery that had been on their side… where was it now? Madrigal’s neck, stretched vulnerable, her smooth cheek to the hot black rock, and the blade, raised high and poised to fall.

His scream was a thing. It clawed its way out of him, gutting him from the inside. It ripped and tore; there was pain, pain to summon, and he tried to work it into magic, but he was too weak. The Wolf had seen to that: Even now Akiva was flanked by revenant guards, their hamsas aimed at him and flooding him with their debilitating sickness. Still he tried, and ripples went through the crowd as the very ground beneath their feet shifted. The scaffold rocked, the executioner had to take a step to steady himself, but it wasn’t enough.

The effort burst the blood vessels in his eyes. Still he screamed. Tried.

The blade glinted its descent, and Akiva fell forward on his hands. He was shredded, empty. Love, peace, wonder: gone. Hope, humanity: gone.

All that remained was vengeance.

The blade was a great and shining thing, like a falling moon.

It bit, and Madrigal was unsheathed.

She was aware of the falling away of flesh.

She still was. She was, but she was not corporeal. She didn’t want to see her head’s disgraceful tumble, but couldn’t help it. Her horns hit the platform first with a clatter, and then there was the ungodly thud of meat before it came to rest, the horns preventing it from rolling.

From this strange new vantage point above her body, she saw it all. She couldn’t not. The eyes had been the body’s apparatus, with their selective focus and lids for closing. She had no such ability now. She saw everything, with no fleshly boundary to divide herself from the air all around her. It was a muted kind of seeing, all directions at once as if her entire being were an eye, but a hazy one. The agora, the hateful crowd. And on the platform facing her own, his scream still warping the air around her: Akiva on his knees, pitched forward and wracked with sobs.

Below her she saw her own body, headless. It swayed to one side and collapsed. It was finished. Madrigal felt tethered to it. She had expected that; she knew souls stayed with their bodies for several days before beginning to ebb. Revenants who had been snatched back from the verge of evanescence had said it felt like a tide carrying them out.

Thiago had ordered her body left on the platform to rot, under guard, so that no one might attempt to glean her soul. She was sorry for the treatment of her body. For all that Brimstone might call bodies “envelopes,” she loved the skin that had carried her through her life, and she wished it could have a more respectful end, but it couldn’t be helped, and anyway, she didn’t intend to be here to see it break down. She had other plans.

She wasn’t certain that it could be done, this idea she clung to. She had nothing but a hint to go on, but she wrapped all her will around it, and all her longing and passion. Everything that she and Akiva had dreamed about, now thwarted, she directed into this one last act: She was going to set him free.

To which end, she would need a body. She had one picked out. It was a good one; she’d made it herself.

She had even used diamonds.

58

58

V ICTORY AND V ENGEANCE

“What’s going on with you, Mad?”

A week earlier, Madrigal had been with Chiro in the barracks. It was dawn, and she had crept into her bunk a mere half hour earlier from a night with Akiva. “What do you mean?”

“Do you ever sleep anymore? Where were you last night?”

“Working,” she said.

“All night?”

“Yes, all night. Though I may have fallen asleep in the shop for a couple of hours.” She yawned. She felt safe in her lies because no one outside Brimstone’s inner circle knew what went on in the west tower, or even knew about the secret passageway through which she came and went. And it was true that she had slept for a little while—just not in the shop. She’d dozed curled against Akiva’s chest and woken to him watching her.

“What?” she’d asked, bashful.

“Good dreams? You were smiling in your sleep.”

“Of course I was. I’m happy.”

Happy.

She thought that was what Chiro really meant when she asked, “What’s going on with you?” Madrigal felt remade. She had never guessed how deep happiness could go. In spite of the tragedy in her childhood and the ever-present press of war, she had mostly considered herself happy. There was almost always something to take delight in, if you were trying. But this was different. It couldn’t be contained. She sometimes imagined it streaming out of her like light.

Happiness. It was the place where passion, with all its dazzle and drumbeat, met something softer: homecoming and safety and pure sunbeam comfort. It was all those things, intertwined with the heat and the thrill, and it was as bright within her as a swallowed star.

Her foster sister was scrutinizing her in silence when a trumpet blast in the city caused her to turn to the window. Madrigal went to her side and looked out. Their barracks were behind the armory, and they could just see the facade of the palace on the far side of the agora, where the Warlord’s gonfalon hung, a vast silk banner that indicated he was in residence. It bore his heraldry—antlers sprouting leaves to signify new growth—and beside it, as Madrigal and Chiro watched, another gonfalon unfurled. This one was blazoned with a white wolf, and though it was too distant to read, they both knew its motto well.

Victory and vengeance.

Thiago had returned to Loramendi.

Chiro’s hands fluttered so that she had to steady them against the window ledge. Madrigal saw her sister’s excitement, even as she fought her own rising bile. She had chosen to take Thiago’s departure and absence as a sign—of fate conspiring in her happiness. But if his absence had been a sign, what did his return signify? The sight of his banner was like a splash of icy water. It couldn’t douse her happiness, but it made her want to curl around it and protect it.

She shivered.

Chiro noticed. “What’s the matter? Are you afraid of him?”

“Not afraid,” Madrigal said. “Only anxious that I gave offense, disappearing like I did.” Her story had been that she’d drunk too much grasswine and, overcome by nerves, had hidden in the cathedral, where she’d fallen asleep. She studied her sister’s expression and asked, “Was he… very angry?”

“No one likes to be rejected, Mad.”

She took that as a yes. “Do you think it’s over now, though? That he’s through with me?”

“One way you could make sure,” said Chiro. She was glib, jesting—surely—but her eyes were bright. “You could die,” she said. “Resurrect ugly. He’d leave you alone then.”

Madrigal should have known then—to take care, at least. But she hadn’t the soul for suspicion. Her trust was her undoing.

59

59

T HE W ORLD R EMADE

“I can’t save you.”

Brimstone. Madrigal looked up. She was on the floor in the corner of her barren prison cell, and didn’t expect saving. “I know.”

He approached the bars, and she held herself still, chin raised, face blank. Would he spit at her, as others had? He didn’t have to. The simple fact of Brimstone’s disappointment was worse than anything others could hurl at her.

“Have they hurt you?” he asked.

“Only by hurting him.”

Which was worse a torture than she could have believed. Wherever they were keeping Akiva, it was just near enough that she could hear his screams when they crested into full agony. They rose, wavering audible at irregular intervals, so she never knew when the next one was coming, and had lived the past days in a state of sick expectancy.

Brimstone studied her. “You love him.”

She could only nod. She’d held up so well until now, high dignity and a hard veneer, not letting them see how inside she was dissolving, as if her evanescence had already begun. But under Brimstone’s scrutiny, her lower lip began to tremble. She crushed her knuckles against it to still it. He was silent, and once she thought she could trust her voice, she said, “I’m sorry.”

“For what, child?”

Was he mocking her? His ovine face had always been impossible to read. Kishmish was on his horn, and the creature’s posture mimicked his master’s, the tilt of his head, the hunch of his shoulders. Brimstone asked, “Are you sorry for falling in love?”

“No. Not for that.”

“Then what?”

She didn’t know what he wanted her to say. In the past, he had told her that all he ever wanted was the truth, as plain as she could make it. So what was the truth? What was she sorry for?

“For getting caught,” she said. “And… for making you ashamed.”

“Should I be ashamed?”

She blinked at him. She would never have believed that Brimstone would taunt her. She had thought he just wouldn’t come, that her last sight of him would be on the palace balcony as he awaited her execution along with everyone else.

He said, “Tell me what it is you have done.”

“You know what I’ve done.”

“Tell me.”

It was to be taunting, then. Madrigal bowed to it. She gave him a recitation. “High treason. Consorting with the enemy. Endangering the perpetuity of the chimaera race and everything we’ve fought for for a thousand years—”

He cut her off. “I know your sentence. Tell me in your own words.”

She swallowed, trying to divine what he wanted. Haltingly, she said, “I… I fell in love. I—” She shot him an abashed glance before revealing what she had so far told no one. “It started at the Battle of Bullfinch. The fighting was over. It was after, during the gleaning. I found him dying and I saved him. I didn’t know why; it felt like the only thing. Later… later I thought it was because we were meant for something.” Her voice dropped and her cheeks flamed as she whispered, “To bring peace.”

“Peace,” Brimstone echoed.

How childish it seemed, considering where she was now, to have believed there was some divine intention in their love. And yet, how beautiful it had been. What she had shared with Akiva could not be touched by shame. Madrigal lifted her voice to say, “We dreamed together of the world remade.”

There followed a long silence, Brimstone just looking at her, and if she hadn’t made a game of trying to outstare him as a child she would have been ill-equipped to endure it. Even so, she was burning to blink by the time he finally spoke. “And for that,” he said, “I should be ashamed of you?”

All the cogs of misery within Madrigal froze. It felt as if her blood stopped moving. She didn’t hope… she didn’t dare. What did he mean? Would he say more?

No. He breathed a heavy sigh, and said again, “I can’t save you.”

“I… I know.”

“Yasri sent you these.” He thrust a cloth bundle through the bars, and Madrigal took it. It was warm, fragrant. She unwrapped it and saw the horn-shaped pastries Yasri had been stuffing her with for years in a vain effort to fatten her up. Tears sprang to her eyes.

She laid them gently aside. “I can’t eat,” she said. “But… tell her I did?”

“I will.”

“And… Issa and Twiga.” An ache swelled in her throat. “Tell them…” She had to press her knuckles to her lips again. She was barely holding it together. Why was it so much more difficult in Brimstone’s presence? Before he came in, anger had kept her hard.

Though she had yet to give him a message to relay, he said, “They know, child. They already know. And they aren’t ashamed of you, either.”

Either.

It was as close as he would come, and it was good enough. Madrigal burst into tears. She leaned into the bars, head down, and wept, and she felt his hand settle on her neck, and wept harder.

He stayed with her, and she knew that no one but Brimstone—save the Warlord himself—could have overridden Thiago’s direct order that she have no visitors. He had power, but even he couldn’t overrule her sentence. Her crime was just too grave, her guilt too plain.

After she had cried, she felt at once hollow and… better, as if the salt of all her unshed tears had been poisoning her, and now she was cleansed. She leaned against the bars; Brimstone was hunkered down on the other side. Kishmish started chirping regular little snips that Madrigal knew were a combination boss/beg, so she broke off bits of Yasri’s pastry and fed them to him.

“Prison picnic,” she said, with a weak effort at a smile, which then bit off abruptly.

They both heard it at the same time—a scream of such pure wretchedness that Madrigal had to fold over herself, press her face to her knees and her hands to her ears, pitching herself in darkness, silence, denial. It didn’t work. This fresh scream was already in her skull, and even after it stopped, its echo stayed inside her.

“Who will be first?” she asked Brimstone.

He knew what she meant. “You. With the seraph watching.”

In a moment of strange detachment, she said, “I thought he would decide the opposite, and make me watch.”

“I believe,” said Brimstone with some hesitation, “that he isn’t… finished with him yet.”

A small sound escaped Madrigal’s throat. How long? How long would Thiago make him suffer?

She asked Brimstone, “Do you remember the wishbone, when I was younger?”

“I remember.”

“I finally made a wish on it. Or… a hope, I suppose, as there was no real magic in it.”

“Hope is the real magic, child.”

Images flashed through her mind. Akiva smiling his smile of light. Akiva beaten to the ground, his blood running into the sacred spring. The temple in flames as the soldiers dragged them away, the requiem trees starting to catch fire, too, and all the evangelines that lived in them. She reached into her pocket and produced the wishbone she had brought to the grove that last time. It was intact. They had never gotten the chance to break it.

She thrust it at Brimstone. “Here. Take it, trample it, throw it away. There is no hope.”

“If I believed that,” Brimstone said, “I wouldn’t be here now.”

What did that mean?

“What do I do, child, day after day, but fight against a tide? Wave after wave upon the shore, each wave licking farther up the sand. We won’t win, Madrigal. We can’t beat the seraphim.”

“What? But—”

“We can’t win this war. I’ve always known it. They are too strong. The only reason we’ve held them off this long is because we burned the library.”

“The library?”

“Of Astrae. It was the archive of the seraph magi. The fools kept all their texts in one place. They were so jealous of their power, they didn’t allow copies. They didn’t want any upstarts to challenge them, so they hoarded their knowledge, and they took only apprentices they could control, and kept them close. That was their first mistake, keeping all their power in one place.”

Madrigal listened, rapt. Brimstone, telling her things. History. Secrets. Almost afraid to break the spell, she asked, “What was their next mistake?”

“Forgetting to fear us.” He was silent a moment. Kishmish hopped back and forth from one of his horns to the other. “They needed to believe we were animals, to justify the way they used us.”

“Slaves,” she whispered, hearing Issa’s voice in her head.

“We were pain thralls. We were the source of their power.”

“Torture.”

“They told themselves we were dumb beasts, as if that made it all right. They had five thousand beasts in their pits who weren’t dumb at all, but they believed their own fiction. They didn’t fear us, and that made it easy.”

“Made what easy?”

“Destroying them. Half the guards didn’t even understand our language, were happy to believe it was just grunts and roars we screamed in our agony. They were fools, and we killed them, and we burned everything. Without magic the seraphim lost their supremacy, and all these years, they have not recovered it. But they will, even without the library. Your seraph is proof that they are rediscovering what they lost.”

“But… No. Akiva’s magic, it isn’t like that—” She thought of the living shawl he’d made her. “He would never use it as a weapon. He only wanted peace.”

“Magic isn’t a tool of peace. The price is too high. The only way I can keep using it, cycling souls through death after death, is by believing that we are keeping alive until… until the world can be remade.”

Her words.

He cleared his throat. It sounded like gravel churning. Was it possible, was he telling her that he…?

He said, “I dream it, too, child.”

Madrigal stared.

“Magic won’t save us. The power it would take to conjure on such a scale, the tithe would destroy us. The only hope… is hope.” He still held the wishbone. “You don’t need tokens for it—it’s in your heart or nowhere. And in your heart, child, it has been stronger than I have ever seen.” He slipped the bone into his breast pocket, then rose from his lion-haunched crouch and turned. Madrigal’s heart cried out at the thought that he was leaving her alone.

But he only paced to the small window on the far wall and looked out. “It was Chiro, you know,” he said, an abrupt change of subject.

Madrigal knew.

Chiro, who had the wings to follow her, and who hid in the grove, and saw.

Chiro, who, like Thiago’s lapdog, betrayed her for a pat on the head.

“Thiago promised her human aspect,” Brimstone said. “As if it were a promise he could keep.”

Stupid Chiro, thought Madrigal. If that was her hope, she had chosen her alliance poorly. “You won’t honor his promise?”

With a dark look, Brimstone replied, “She should make best efforts to never need another body. I have a string of moray eel teeth I never thought I would be tempted to use.”

Moray eel? Madrigal couldn’t tell if he was serious. Probably. She felt almost sorry for her sister. Almost. “To think I wasted diamonds on her.”

“You were true to her, even if she was not to you. Never repent of your own goodness, child. To stay true in the face of evil is a feat of strength.”

“Strength,” she said with a little laugh. “I gave her strength, and look what she did with it.”

He scoffed. “Chiro is not strong. Her body may have been wrought with diamonds, but her soul within will be a soft mollusk thing, wet and shrinking.”

It was an unlovely image, but it felt just about right.

Brimstone added, “And easily pushed aside.”

Madrigal cocked her head. “What?”

Out in the corridor: sounds. Was someone coming? Was it time? Brimstone spun toward her. “The revenant smoke,” he said, quick and clipped. “You know what is in it.”

She blinked. Why was he talking about the smoke? There would be none of it for her. But he was looking at her so intently. She nodded. Of course she knew. The incense was arum and feverfew, rosemary, and asafetida resin for the sulfur smell.

“You know why it works,” he said.

“It makes a path for the soul to follow, to the vessel. The thurible, or the body.”

“Is it magic?”

Madrigal hesitated. She’d helped Twiga make it often enough. “No,” she said, distracted, as the sounds in the corridor grew louder. “It’s just smoke. Just a path for the soul.”

Brimstone nodded. “Not unlike your wishbone. It isn’t magic, just a focus for the will.” He paused. “A powerful will might not even need it.”

His look burned at her, steady. He was trying to tell her something. What?

Madrigal’s hands started to shake. She didn’t understand, quite, but something was starting to take shape, out of magic and will. Smoke and bone.

At the door, the bolts drew back. Madrigal’s heart pounded. Her wings made the ineffectual fluttering of a caged bird. The door opened and Thiago framed himself in it like a picture. As ever, he was clad all in white, and Madrigal realized for the first time why he wore white: It was a canvas for the blood of his victims, and now his surcoat was livid with it.

With Akiva’s blood.

Thiago’s face flashed anger when he saw Brimstone in the room. But he didn’t risk a battle of wills he couldn’t win. He inclined his head to the sorcerer and faced Madrigal. “It’s time,” he said. His voice, perversely, was soft, as if he were coaxing a child to sleep.

She said nothing, fought for calm. Thiago wasn’t fooled. His wolf senses could smell the tang of her fear. He smiled, turning to the guards who awaited his command. “Bind her hands. Pinion her wings.”

“That is unnecessary.” Brimstone.

The guards hesitated.

Thiago faced the resurrectionist and the two stared at each other, their enmity confined to the flaring of nostrils, clenching of jaws. The Wolf repeated his order in precise syllables, and the guards scurried to carry it out: into the cell, wrestling Madrigal’s wings together and piercing them through with iron clips to secure them. Her hands were easier; she didn’t struggle. Once she was fully trussed, they shoved her toward the door.

Brimstone had one last surprise. He told Thiago, “I have designated someone to bless Madrigal’s evanescence.”

The blessing was a sacred ritual that she had assumed she would be denied. Thiago, apparently, had assumed the same. He narrowed his eyes and said, “You think you’re getting anyone close enough to glean her—”

Brimstone cut him short. “Chiro,” he said. Madrigal flinched. To Thiago, he said, “I can’t imagine you would object to her.”

Thiago did not. “Fine.” To the guards, he said, “Go.”

Chiro. It was so deeply wrong, so profane, that Madrigal’s betrayer should be the one to grant her soul peace, that for an instant she thought she had misconstrued everything that Brimstone had just said to her, that this was one final punishment heaped upon the others. Then he smiled. A wily uplift of the line of his stern ram’s mouth, and it struck her. It exploded behind her eyes.

Soft mollusk thing. Easily pushed aside.

The guard gave Madrigal another shove and she was out the door, her mind racing to encompass this wild new notion in the short time that was left to her.