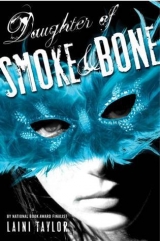

Текст книги "Daughter of Smoke & Bone"

Автор книги: Лэйни Тейлор

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

30

30

Y OU

She led him to her flat, all the while thinking, Stupid, stupid, what are you doing?

Answers, she told herself. I’m getting answers.

She hesitated at the elevator, unsure about being in so small a space with the seraph, but he wasn’t in any state to climb stairs, so she pushed the button. He followed her in, seeming unfamiliar with the principle of elevators, and startled slightly when the mechanism chugged to life.

In her flat, she dropped her keys in a basket by the door and looked around. On the wall: her Angel of Extinction wings, uncannily like his wings. If he noticed the similarity, his face gave away nothing. The space was too small for the wings to be spread to their full span, so they were suspended like a canopy, half-sheltering the bed, which was a deep teak bench piled princess-and-the-pea with feather mattresses. It was unmade and lost in an avalanche of old sketchbooks that Karou had been leafing through the night before, keeping company in the only way she could with her family.

One lay open to a portrait of Brimstone. She saw the angel’s jaw clench at the sight of it, and she grabbed it and clutched it to her chest. He went to the window and looked out.

“What’s your name?” she asked.

“Akiva.”

“And you know mine how?”

A long beat. “The old man.”

Izîl. Of course. But… a thought struck her. Hadn’t Razgut said Izîl leapt to his death to protect her? “How did you find me?” she asked.

It was dark outside, and Akiva’s eyes reflected orange in the window glass. “It wasn’t difficult,” was all he said.

She was going to ask him to be specific, but he closed his eyes and leaned his brow against the glass. She said, “You can sit down,” and gestured to her deep green velvet armchair. “If you’re not going to burn anything.”

His lips made a grim twist that was like the joyless cousin of a smile. “I won’t burn anything.”

He loosed the buckle on the leather straps that crossed his chest, and his swords, sheathed between his shoulder blades, fell to the floor with two thunks that Karou did not think her downstairs neighbor would appreciate. Then Akiva sat, or rather collapsed, in the chair. Karou shoved her sketchbooks aside to make a space for herself on the bed, and seated herself in lotus position facing him.

The flat was tiny—just room for the bed and the chair and a set of carved nesting tables, all atop Karou’s splurge of a Persian carpet, haggled for while it was still on the loom in Tabriz. One wall was all bookcases, facing one all of windows, and off the entry hall: a tiny kitchen, tinier closet, and a bathroom roughly the size of a shower stall. The ceilings were a fairly preposterous twelve feet, making even the main room taller than it was wide, so Karou had built a loft above the bookcases, which she had to climb to reach it, just deep enough to lounge on Turkish cushions and take in the view out the high windows: a direct line over the rooftops of Old Town to the castle.

She watched Akiva. He had let his head drop back; his eyes were closed. He looked so weary. He was rolling one shoulder gingerly, wincing as if it pained him. She considered offering him tea—she could have used some herself—but it felt too much like playing hostess, and she struggled to remember the dynamic between them: They were enemies.

Right?

She studied him, mentally correcting the drawings she’d done from memory. Her fingers itched to snatch up a pencil and draw him from life. Stupid fingers.

He opened his eyes and caught her looking. She blushed. “Don’t get too comfortable,” she said, discomposed.

He struggled upright. “I’m sorry. It’s like this, after battle.”

Battle. He watched guardedly as she processed the idea. She said, “Battle. With chimaera. Because you’re enemies.”

He nodded.

“Why?”

“Why?” he repeated, as if the notion of enemies needed no justification.

“Yes. Why are you enemies?”

“We have always been. The war had been going on for a thousand years—”

“That’s weak. Two races can’t have been born enemies, can they? It had to start somewhere.”

A slow nod. “Yes. It started somewhere.” He rubbed his face with his hands. “What do you know of chimaera?”

What did she know? “Not a lot,” she admitted. “Until the night you attacked me, I didn’t even know there were more than the four of them. I didn’t know they were an entire race.”

He shook his head. “They aren’t one race. They’re many, allied.”

“Oh.” Karou supposed that made sense, with how unalike they were. “Does that mean there are others like Issa, like Brimstone?”

Akiva nodded. The idea gave new shades of reality to the world Karou had glimpsed. She imagined scattered tribes in vast landscapes, a whole village of Issas, families of Brimstones. She wanted to see them. Why had she been kept from them?

Akiva said, “I don’t understand what your life has been. Brimstone raised you, but just in the shop? Not in the fortress itself?”

“I didn’t even know what was on the other side of the inner door until that night.”

“He took you inside, then?”

Karou pursed her lips, remembering the Wishmonger’s fury. “Sure. Let’s say that’s what happened.”

“And what did you see there?”

“Why would I tell you that? You’re enemies, in which case, you’re my enemy, too.”

“I’m not your enemy, Karou.”

“They’re my family. Their enemies are mine.”

“Family,” Akiva repeated, shaking his head. “But where did you come from? Who are you, really?”

“Why does everybody ask me that?” Karou asked, animated by a flash of anger, though it was something she had wondered herself almost every day since she was old enough to understand the extreme oddness of her circumstances. “I’m me. Who are you?”

It was a rhetorical question, but he took it seriously. He said, “I’m a soldier.”

“So what are you doing here? Your war is there. Why did you come here?”

He took a deep, shuddering breath, sank back once more into the chair. “I needed… something,” he said. “Something apart. I have lived war for half a century—”

Karou interrupted him. “You’re fifty?”

“Lives are long, in my world.”

“Well, you’re lucky,” said Karou. “Here, if you want long life, you have to yank out all your teeth with pliers.”

The mention of teeth brought a dangerous flicker to his eyes, but he said only, “Long life is a burden, when it’s spent in misery.”

Misery. Did he mean himself? She asked him.

His eyes fluttered shut as if he’d been struggling to keep them open and abruptly abandoned the fight. He was silent for so long that Karou wondered if he’d fallen asleep, and gave up on her question. It felt intrusive, anyway. And she sensed he had meant himself. She thought of the way he’d looked in Marrakesh. What made the life go out of somebody’s eyes like that?

Again the caretaker impulse came to her, to offer him something, but she resisted it. She let herself stare at him—the cut of his features, the deep black of his brows and lashes, the bars inked on his hands, which were splayed open on the chair arms. With his head tilted back, she could see the welt on his neck and, a little higher up, the steady pulse of his jugular vein.

Once more his physicality struck her, that he was a flesh-and-blood being, though unlike any she had ever seen or touched. He was a melding of elements: fire and earth. She would have thought an angel would have something of air, but he didn’t. He was all substance: powerful and rugged and real.

His eyes opened and she jumped, caught staring once again. How many times was she going to blush, anyway?

“I’m sorry,” he said, his voice faint. “I think I fell asleep.”

“Um.” She couldn’t help it. “Do you need some water?”

“Please.” He sounded so grateful she felt a pang of guilt for not offering sooner.

She untangled her legs from their lotus, rose, and brought him a glass of water, which he drained in a draft. “Thank you,” he said in a weirdly heartfelt way, as if he were thanking her for something much more profound than a glass of water.

“Uh. Uh-huh,” she said, awkward. She felt like she was hovering, standing there. There was really nowhere in the room to go except the bed, so she scooted back onto it. She kind of wanted to take off her boots, but that was something you didn’t do if there was any chance you might have to quickly flee or kick someone. Judging from Akiva’s plain exhaustion, she didn’t think she was in danger of either. The only danger was of foot smell.

She kept her boots on.

She said, “I still don’t get why you burned the portals. How does that end your war?”

Akiva’s hands tightened on the empty water glass. He said, “There was magic coming through the doorways. Dark magic.”

“From here? There’s no magic here.”

“Says the flying girl.”

“Okay, but that’s because of a wish, from your world.”

“From Brimstone.”

She acknowledged this with a nod.

“So you know that he’s a sorcerer.”

“I… Uh. Yeah.” She’d never really thought of Brimstone as a sorcerer. Did he do more than manufacture wishes? What did she know, really, and how much did she not know? Her ignorance was like standing in pure dark that could be either a closet or a vast, starless night.

A kaleidoscope of images whirled in her mind. The fizz of magic when she stepped into the shop. The array of teeth and gems, the stone tables in that underground cathedral, laid out with the dead… the dead who were not, as Karou had learned the hard way, actually dead. And she remembered Issa admonishing her not to make Brimstone’s life any harder—his “joyless” life, as she had said. His “relentless” work. What work?

She picked up a sketchbook at random, fanning past drawings of her chimaera so that they made a jerky kind of animation. “What was the magic?” she asked Akiva. “The dark magic.”

He didn’t answer, and she expected when she looked up to see that he had fallen asleep again, but he was watching the images flash past in her sketchbook. She snapped it closed, and his eyes fixed on her instead. Again, that vivid searching.

“What?” she asked, discomfited.

“Karou,” he said. “Hope.”

She raised her eyebrows, as if to say So?

“Why did he give you that name?”

She shrugged. It was getting tiring, not knowing anything. “Why did your parents name you Akiva?”

At the mention of his parents, Akiva’s face hardened, and the vivid watchfulness of his gaze glazed back to fatigue. “They didn’t,” he said. “A steward named me from a list. Another Akiva had been killed. The name opened up.”

“Oh.” Karou didn’t know what to make of that. It made her own strange upbringing seem cozy and familial by comparison.

“I was bred to be a soldier,” Akiva said in a hollow voice, and he closed his eyes again, tightly this time, as if gripped by a wave of pain. He was silent for a long time, and when he spoke again, he said far more than she expected.

“I was taken from my mother at five years old. I don’t remember her face, only that she did nothing when they came for me. It’s my earliest memory. I was so small that they were just legs, these looming soldiers surrounding me. They were the palace guard, so their shin plates were silver, and I could see myself mirrored in them, in all of them, my own terrified face over and over. They took me to the training camp, where I was one of a legion of terrified children.” He swallowed. “Where they punished our terror and taught us to conceal it. And that became my life, the concealment of terror, until I didn’t feel it anymore, or anything else.”

Karou couldn’t help imagining him as a child, afraid and forsaken. Tenderness welled up in her like tears.

In a fading voice, he said, “I exist only because of war—a war that began a thousand years ago with a massacre of my people. Babies, elders, no one spared. In Astrae, the capital of the Empire, the chimaera rose up to massacre the seraphim. We are enemies because the chimaera are monsters. My life is blood because my world is beasts.

“And then I came here, and humans…” A dreamlike wonder shaded into his tone. “Humans were walking freely, weaponless, gathering in the open, sitting in plazas, laughing, growing old. And I saw a girl… a girl with black eyes and gemstone hair, and… sadness. She had a sadness that was so deep, but it still could turn to light in a second, and when I saw her smile I wondered what it would be like to make her smile. I thought… I thought it would be like the discovery of smiling. She was connected to the enemy, and though the only thing I wanted to do was look at her, I did what I was trained to do and I… I hurt her. And when I went home, I couldn’t stop thinking about you, and I was so grateful that you had defended yourself. That you didn’t let me kill you.”

You. Karou did not miss the pronoun shift. She sat unblinking, barely breathing.

“I came back to find you,” Akiva said. “I don’t know why. Karou. Karou. I don’t know why.” His voice was so faint she could barely hear him. “Just to find you and be in the world that you’re in…”

Karou waited, but he didn’t say any more, and then… something happened in the air around him.

A shimmer, like an aura at first, brightening to light and becoming wings—open and upthrust from his shoulder blades to sprawl over the armchair and sweep the carpet in great arabesques of fire. His glamour had given way, and Karou almost gasped to see his wings revealed, but the flame didn’t catch. It was smokeless, somehow self-contained. The subtle shifts of the fire-feathers were hypnotic, and Karou breathed again, deeply, and sat watching them for minutes as Akiva’s features relaxed into something like peacefulness. This time he was truly asleep.

She got up and took the water glass from his hands. She turned off the light. His wings were sufficient illumination, even for drawing. She got out her sketchbook and a pencil, and she drew Akiva asleep at the locus of his vast wings, and then from memory, with his eyes open. She tried to capture the precise shape of them; she used charcoal for the heavy black kohl that rimmed them and made him look so exotic, and she couldn’t take leaving his fiery irises colorless. She grabbed a watercolor box and painted. She drew and painted for a long time, and he didn’t move except for the soft rise and fall of his chest and the glimmer of his wings, which cast the room in a firelight glow.

Karou didn’t plan to sleep, but some time after midnight she subsided, still half on the landslide of her sketchbooks, to “rest her eyes” for a moment. She fell into dreams, and when she woke just before dawn—something woke her, a quick, bright sound—the room around her was, for a blink, entirely unfamiliar. Only the wings on the wall over her were not, and gave her a surge of pleasure, and then it all slid away as dreams do. She was in her flat, of course, on her bed, and the sound that had awakened her was Akiva.

He was standing over her, and his eyes were molten. They were wide, his orange irises ringed around in white, and he was holding, one in each hand, her crescent-moon knives.

31

31

R IGHT

Karou sat up with a suddenness that sent sketchbooks skidding off the bed. Her pencil was still in her hand, and the thought struck her: always with the ridiculous weapon, where this angel was concerned. But even as she adjusted her grip on it, ready to stab, Akiva was backing away, lowering the knives.

He set them where he had found them, where she had left them, in their case, atop the nesting tables. They would have been practically under his nose when he woke.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I didn’t mean to frighten you.”

Just then, lit only by the flicker of his wings, the sight of him was so… right, somehow. He was right. It made no sense at all, but the feeling flooded through Karou, and whatever it was, it was as sweet as a patch of sun on a glossy floor and, like a cat, she just wanted to curl up in it.

She tried to pretend she hadn’t been about to stab him with a pencil. “Well,” she said, stretching and letting it drop casually out of her hand. “I don’t know your customs, but here, if you don’t want to frighten someone, you don’t go looming over their sleeping body with knives.”

Was that a smile? No. A twitch at the corners of his stern mouth; it didn’t qualify.

She caught sight of the sketchbook open before her, the evidence of her late-night portrait session right there for him to see. She flipped it quickly shut, though he’d of course have seen it while she was still sleeping.

How could she have fallen asleep with this stranger in her flat? How could she have brought this stranger to her flat?

He didn’t feel like a stranger.

“They’re unusual,” Akiva said, gesturing to the knife case.

“I just got them. Beautiful, aren’t they?”

“Beautiful,” he agreed, and he might have been talking about the knives, but he was looking straight at her.

She flushed, suddenly conscious of her appearance—mussed hair, sleep drool?—then got angry. What did it matter what she looked like? What exactly was going on here? She shook herself and climbed off the bed, trying to find a space in the tiny room outside his radiant aura. It was impossible.

“I’ll be right back,” she said, and stepped into the hall and then the tiny bathroom. Separated from him, she experienced a sharp fear that she would return to find him gone. She relieved herself, wondering if seraphim were above such mundane needs—though judging from the duskiness of his jaw, Akiva was not above the need for a razor—then splashed water on her face and brushed her teeth. She ran a brush through her hair, and every moment she lingered, her anxiety grew that when she returned she would find just an empty room, balcony door standing open and the whole universe of sky above, giving no hint which way he’d gone.

But he was still there. His wings were glamoured gone again, his swords strapped in place at his back, innocuous in their decorative leather sheaths.

“Um,” she said, “bathroom’s in there, if, uh…”

He nodded and went past her, awkward as he tried to wedge his invisible wings into the tiny space and get the door closed.

Karou hurriedly changed into clean clothes, then went to the window. It was still dark out. The clock said five. She was starving, and knew from her previous morning’s foraging that there was nothing even remotely edible in the kitchen. When Akiva emerged, she asked, “Are you hungry?”

“As if I might die of it.”

“Come on, then.” She picked up her coat and keys and started toward the door, then paused and changed direction. She went out onto the balcony instead, climbed up onto the balustrade, glanced back over her shoulder at Akiva, and stepped right off.

Six stories to the street, she landed light as hopscotch, unable to suppress a smile. Akiva was right beside her, unsmiling as ever. She couldn’t quite imagine him smiling; he was so somber, but wasn’t there something in the way he looked at her? There, in that sidelong glance: a hint of wonder? She recalled the things he’d said in the night, and now, seeing flickers of feeling interrupt the sad gravity of his face, it shot a pang through her heart. What had his life been like, given over so young to war? War. It was an abstraction to her. She couldn’t conceptualize its reality, not even the edges of its reality, but the way Akiva had been—dead-eyed—and the way he looked at her now, it made her feel as if he was coming back from the dead for her, and that seemed a tremendous thing, and an intimate one. The next time their eyes met, she had to look away.

She took him to her corner bakery. It wasn’t open yet, but the baker sold them hot loaves through the window—honey-lavender, fresh from the oven and still steaming in their crinkly brown bags—and then Karou did what anyone would do if they could fly and found themselves out on the streets of Prague at dawn with loaves of hot bread to eat.

She flew, gesturing to Akiva to follow, up into the sky and over the river, to perch on the high, cold cupola of the cathedral bell tower, and watch the sun rise.

Akiva kept close behind her, watching the snap of her hair, its long tendrils taking on the damp of dawn. Karou had been wrong to suppose her flying didn’t surprise him. It was only that he had learned over many years to crush down all feeling, all reaction. Or he thought he had. In the presence of this girl, it seemed, nothing was certain.

There was a neatness in the way she sliced through the air. It was magic—not glamoured wings, but simply the will to fly made manifest. A wish, he supposed, from Brimstone’s own supply. Brimstone. The thought of the sorcerer came on like an ink splash, a black thought against the brightness of Karou.

How could something as light as Karou’s graceful flight come from the evil of Brimstone’s magic?

They flew above casual observation, over the river and veering in the direction of the castle, where they circled down toward the cathedral at its heart. It was a Gothic beast, carved and weathered like some tortured cliff battered by ages of storms. Karou alighted upon the cupola of the bell tower. It was not a kind perch. The wind scoured past, full of ice and ill will, and Karou had to gather her hair in her hands and hold it off her face. She produced a pencil—the same one she had brandished at him?—knotted her hair, and shoved the pencil through it; an all-purpose implement. Blue wisps escaped the arrangement and danced across her brow, blowing over her eyes and catching on her lips, which were smiling with uncomplicated, childlike delight. “We’re on the cathedral,” she said to him.

He nodded.

“No. We’re on the cathedral,” she said again, and he thought he was missing something, some nuance lost in language, but then he realized: She was just amazed. Amazed to be perching atop the cathedral, high on the hill above Prague with everything below her. She hugged her arms around the warm bread and stood looking out, and on her face was a naked awe more potent than Akiva could ever recall feeling, even when flying was new. It was likely he had never felt any such thing. His own early flights weren’t occasion for awe or joy—only discipline. But he wanted to be part of the moment that was making her face shine like that, so he moved to her side and looked out.

It was a remarkable sight, the sky beginning to flush pale at the roots, all the towers bathed in a soft glow, the streets of the city still shadowed and aglitter with fireflies of lamplight and the weaving, winking beams of headlights.

“You haven’t come up here before?” he asked.

She turned to him. “Oh, yes, I bring all the boys up here.”

“And if they don’t meet with approval,” he said, “you can always push them off.”

It was the wrong thing to say. Karou’s expression darkened. No doubt she was thinking of Izîl. Akiva admonished himself for making an effort at humor. Of course it would come off all wrong. It had been a long time since he’d had the will to banter.

“The truth is,” Karou said, letting it pass, “I only made the wish for flying a few days ago. I haven’t had a chance to enjoy it yet.”

Again he was surprised; it must have shown this time, because Karou caught his look and said, “What?”

He shook his head. “You were so smooth in the air, and the way you stepped off your balcony without a second’s pause, as if flying is just a part of you.”

She said, “You know, it didn’t occur to me that the wish could wear off. That would have been some punishment for showing off, wouldn’t it? Splat.” She laughed, untroubled by the thought, and said, “I should be more careful.”

“Do the wishes wear off?” he asked.

She shrugged. “I don’t know. I don’t think so. My hair has never changed back.”

“That’s a wish? Brimstone let you use magic on… that?”

“Well. He didn’t exactly approve.” She skewed him a glance that was both sheepish and defiant. “It’s not like he ever let me have any real wishes. Just enough to make minor mischief—Oh.” A thought struck her. “Oops.”

“What?”

“I made a promise last night and forgot all about it.” She rummaged in her coat pocket and pulled out a small coin, on which Akiva glimpsed Brimstone’s likeness. It was there on her palm when she closed her hand; when she opened it, it was gone. “Magic,” she said. “Poof.”

“What did you wish?” he asked.

“Just something stupid. A mean girl somewhere down there is going to wake up happy. Not that she deserves it. Hussy.” She stuck out her tongue at the city, a flash of childish whimsy. “Oh. Here.” She turned to Akiva and thrust one of the bakery bags at him. “You know, so you don’t die.”

While they ate, he saw that she was shivering, and he opened his wings—invisible—so the wind would catch their heat and fan it around her. It seemed to help. She sat down, dangling her legs over the edge, and kicked them casually while she pulled little pieces of bread off her loaf and ate them. He went into a crouch at her side.

“How are you feeling, by the way?” she asked.

“That depends,” he said, feeling sly, as if Karou’s whimsy were catching.

“On?”

“On whether you’re asking because you’re concerned for my well-being, or because you mean to keep me weak and helpless.”

“Oh. Weak and helpless. Definitely.”

“In that case, I feel awful.”

“Good.” She said it seriously enough, but with a glint in her eye. Akiva realized that she had been taking care with her hamsas, to not accidentally turn them in his direction. He was moved, as he had been when he’d awakened to find her sleeping just feet from him, so lovely and vulnerable, and her trust, like Madrigal’s, so unearned.

“I’m feeling better,” he said softly. “Thank you.”

“Don’t thank me. I’m the one who hurt you.”

Shame engulfed him. “Not… not like I hurt you.”

“No,” Karou agreed. “Not like that.”

The wind was spiteful; with an insurgent gust it freed her hair, then danced in to seize it; in an instant it was everywhere, as if a pod of air elementals were trying to make off with it, to line their nests with its blue silk. She scrambled to contend with it; the pencil was lost over the roof’s edge, plunging between flying buttresses, so she held her hair with both hands.

Akiva waited for her to say she was ready to get down out of the wind, but she didn’t. The sun climbed above the hills and she watched as its glow herded night into the shadows where it gathered, all the darker for its density—all of night crowded into the slanting places beyond the reach of the dawn.

After a while she said, “You know last night, you said your earliest memory was of the soldiers coming for you—”

“I told you that?” He was startled.

“What, don’t you remember?” She turned to him, eyebrows twin quirks, cocoa-dark, raised in surprise.

He shook his head, searching his mind. He’d been so ill from the devil’s marks, it was all a fugue, but he couldn’t believe he’d spoken of his childhood, and that day of all days. It made him feel as if he’d dragged that bereft little boy out of the past—as if, in a moment of weakness, he had become him again. He asked, “What else did I say?”

Karou cocked her head. It was the gesture that had saved her in Marrakesh, the quick birdlike tilt, to regard him almost sideways, and Akiva’s heart sped up. “Not much,” she said, after a moment. “You fell asleep after that.” She was clearly lying.

What had he said to her in the night?

“Anyway,” she went on, not meeting his eyes, “you got me thinking, and I was trying to remember my own earliest memory.” She levered herself back to her feet from the roof’s edge, a move that required releasing her hair, which sprang wild back into the wind.

“And?”

“Brimstone.” A hitch in her breathing, a fond and infinitely sad smile. “It’s Brimstone. I’m sitting on the floor behind his desk, playing with the tuft of his tail.”

Playing with the tuft of his tail? That didn’t fit with Akiva’s own idea of the sorcerer, which had been forged by his deepest anguish, seared into his soul like a brand.

“Brimstone,” he said, bitter. “He was good to you?”

Karou was fierce in her reply. Her hair a blue torrent, her eyes hungry, she said, “Always. Whatever you think you know of chimaera, you don’t know him.”

“Isn’t it possible, Karou,” he said slowly, “that it’s you who don’t really know him?”

“What?” she asked. “What exactly don’t I know?”

“His magic, for one thing,” said Akiva. “Your wishes. Do you know what they come from?”

“Come from?”

“It’s not free, Karou. Magic has a price. The price is pain.”