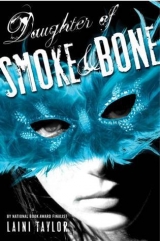

Текст книги "Daughter of Smoke & Bone"

Автор книги: Лэйни Тейлор

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

55

55

C HILDREN OF R EGRET

Once upon a time, before chimaera and seraphim, there was the sun and the moons. The sun was betrothed to Nitid, the bright sister, but it was demure Ellai, always hiding behind her bold sister, who stirred his lust. He contrived to come upon her bathing in the sea, and he took her. She struggled, but he was the sun, and he thought he should have what he wanted. Ellai stabbed him and escaped, and the blood of the sun flew like sparks to earth, where it became seraphim—misbegotten children of fire. And like their father, they believed it their due to want, and take, and have.

As for Ellai, she told her sister what had passed, and Nitid wept, and her tears fell to earth and became chimaera, children of regret.

When the sun came again to the sisters, neither would have him. Nitid put Ellai behind her and protected her, though the sun, still bleeding sparks, knew Ellai was not as defenseless as she seemed. He pled with Nitid to forgive him but she refused, and to this day he follows the sisters across the sky, wanting and wanting and never having, and that will be his punishment, forever.

Nitid is the goddess of tears and life, hunts and war, and her temples are too many to count. It is she who fills wombs, slows the hearts of the dying, and leads her children against the seraphim. Her light is like a small sun; she chases away shadows.

Ellai is more subtle. She is a trace, a phantom moon, and there are only a handful of nights each year when she alone takes the sky. These are called Ellai nights, and they are dark and star-scattered and good for furtive things. Ellai is the goddess of assassins and secret lovers. Temples to her are few, and hidden, like the one in the requiem grove in the hills above Loramendi.

That was where Madrigal took Akiva when they fled the Warlord’s ball.

They flew. He kept his wings veiled, but it didn’t prevent his flying. By land, the requiem grove was unreachable. There were chasms in the hills, and sometimes rope bridges were strung across them—on Ellai nights, when devotees went cloaked to worship at the temple—but tonight there were none, and Madrigal knew they would have the temple to themselves.

They had the night. Nitid was still high. They had hours.

“That is your legend?” Akiva asked, incredulous. Madrigal had told him the story of the sun and Ellai while they flew. “That seraphim are the blood of a rapist sun?”

Madrigal said blithely, “If you don’t like it, take it up with the sun.”

“It’s a terrible story. What a brutal imagination chimaera have.”

“Well. We have had brutal inspiration.”

They reached the grove, and the dome of the temple was just visible through the treetops, silver mosaics glinting patterns through the boughs.

“Here,” said Madrigal, slowing with a backbeat to descend through a gap in the canopy. Her whole body thrilled with night wind and freedom, and with anticipation. In the back of her mind was fear of what would come later—the repercussions of her rash departure. But as she moved through the trees, it was drowned out by leaf rustle and wind music, and by the hish-hish all around. Hish-hish went the evangelines, serpent-birds who drank the night nectar of the requiem trees. In the dark of the grove, their eyes shone silver like the mosaics of the temple roof.

Madrigal reached the ground, and Akiva landed beside her in a gust of warmth. She faced him. They were still wearing their masks. They could have stripped them off while flying, but they hadn’t. Madrigal had been thinking of this moment, when they would stand face-to-face, and she had left her mask on because in her imagining, it was Akiva who took hers off, as she did his.

He must have imagined the same thing. He stepped toward her.

The real world, already a distant thing—just a crackle of fireworks at horizon’s edge—faded away entirely. A high, sweet thrill sang through Madrigal as if she were a lute string. Akiva took off his gloves and dropped them, and when he touched her, fingertips trailing up her arms and neck, it was with his bare hands. He reached behind her head, untied her mask, and lifted it away. Her vision, which had been narrowed all night to what she could see through its small apertures, opened, and Akiva filled her sight, still wearing his comical mask. She heard his soft exhalation and murmur of “so beautiful,” and she reached up and took off his disguise.

“Hello,” she whispered, as she had when they had come together in the Emberlin and happiness had bloomed in her. That happiness was like a spark to a firework, compared with what filled her now.

He was more perfect even than she remembered. At Bullfinch he had lain dying, ashen, slack, and still beautiful for all that. Now, in the full flush of health and the blood-thrum of love, he was golden. He was ardent, gazing at her, hopeful and expectant, inspired, beguiled, glad. He was so alive.

Because of her, he was alive.

He whispered back, “Hello.”

They stared, amazed to be facing each other after two years, as if they were figments conjured out of wishing.

Only touching could make the moment real.

Madrigal’s hands shook as she raised them, and steadied when she laid them against the solidity of Akiva’s chest. Heat pulsed through the fabric of his shirt. The air in the grove was rich enough to sip, full enough to dance with. It was like a presence between them—and then not, as she stepped close.

His arms encircled her and she tilted up her face to whisper, once more, “Hello.”

This time when he said it back, he breathed it against her lips. Their eyes were still open, still wide with wonder, and they only let them flutter shut when their lips finally met and another sense—touch—could take over in convincing them that this was real.

56

56

T HE I NVENTION OF L IVING

Once upon a time, there was only darkness, and there were monsters vast as worlds who swam in it. They were the Gibborim, and they loved the darkness because it concealed their hideousness. Whenever some other creature contrived to make light, they would extinguish it. When stars were born, they swallowed them, and it seemed that darkness would be eternal.

But a race of bright warriors heard of the Gibborim and traveled from their far world to do battle with them. The war was long, light against dark, and many of the warriors were slain. In the end, when they vanquished the monsters, there were a hundred left alive, and these hundred were the godstars, who brought light to the universe.

They made the rest of the stars, including our sun, and there was no more darkness, only endless light. They made children in their image—seraphim—and sent them down to bear light to the worlds that spun in space, and all was good. But one day, the last of the Gibborim, who was called Zamzumin, persuaded them that shadows were needed, that they would make the light seem brighter by contrast, and so the godstars brought shadows into being.

But Zamzumin was a trickster. He needed only a shred of darkness to work with. He breathed life into the shadows, and as the godstars had made the seraphim in their own image, so did Zamzumin make the chimaera in his, and so they were hideous, and forever after the seraphim would fight on the side of light, and chimaera for dark, and they would be enemies until the end of the world.

Madrigal laughed sleepily. “Zamzumin? That’s a name?”

“Don’t ask me. He’s your forefather.”

“Ah, yes. Ugly Uncle Zamzumin, who made me out of a shadow.”

“A hideous shadow,” said Akiva. “Which explains your hideousness.”

She laughed again, heavy and lazy with pleasure. “I always wondered where I got it. Now I know. My horns are from my father’s side, and my hideousness is from my huge, evil monster uncle.” After a pause, Akiva nuzzling her neck, she added, “I like my story better. I’d rather be made from tears than darkness.”

“Neither is very cheerful,” said Akiva.

“I know. We need a happier myth. Let’s make one up.”

They lay entwined atop their clothes, which they had draped over a bank of shrive moss behind Ellai’s temple, where a delicate rill burbled past. Both moons had slipped beyond the canopy of the trees, and the evangelines were falling silent as the requiem blooms closed their white buds for the night. Soon Madrigal would have to leave, but they were both pushing the thought away, as if they could deny the dawn.

“Once upon a time…” said Akiva, but his voice trailed off as his lips found Madrigal’s throat. “Mmm, sugar. I thought I got it all. Now I’ll have to double-check everywhere.”

Madrigal squirmed, laughing helplessly. “No, no, it tickles!”

But Akiva would retaste her neck, and it didn’t really tickle so much as it tingled, and she stopped protesting soon enough.

It was some time before they got back around to their new myth.

“Once upon a time,” Madrigal murmured later, her face now resting on Akiva’s chest so that the curve of her left horn followed the line of his face, and he could tilt his brow against it. “There was a world that was perfectly made and full of birds and striped creatures and lovely things like honey lilies and star tenzing and weasels—”

“Weasels?”

“Hush. And this world already had light and shadow, so it didn’t need any rogue stars to come and save it, and it had no use for bleeding suns or weeping moons, either, and most important, it had never known war, which is a terrible, wasteful thing that no world ever needs. It had earth and water, air and fire, all four elements, but it was missing the last element. Love.”

Akiva’s eyes were closed. He smiled as he listened, and stroked the soft down of Madrigal’s fur-short hair, and traced the ridges of her horns.

“And so this paradise was like a jewel box without a jewel. There it lay, day after day of rose-colored dawns and creature sounds and strange perfumes, and waited for lovers to find it and fill it with their happiness.” Pause. “The end.”

“The end?” Akiva opened his eyes. “What do you mean, the end?”

She said, smoothing her cheek against the golden skin of his chest, “The story is unfinished. The world is still waiting.”

He said wistfully, “Do you know how to find it? Let’s leave before the sun rises.”

The sun. The reminder stilled Madrigal’s lips from their new course up the curve of Akiva’s shoulder, the one scarred with the reminder of their first meeting, at Bullfinch. She thought how she might have left him bleeding, or worse, finished him, but some ineluctable thing had stopped her so that they might be here, now. And the idea of disentangling, dressing, leaving, gave rise to a reluctance so powerful it hurt.

There was dread, too, of what her disappearance might have stirred up back at Loramendi. An image of Thiago, angry, intruded into her happiness, and she pushed it away, but there was no pushing away the sunrise. In a mournful voice, she said, “I have to go.”

Akiva said, “I know,” and she lifted her face from his shoulder and saw that his wretchedness matched her own. He didn’t ask, “What will we do?” and she didn’t, either. Later they would talk of such things; on that first night, they were shy of the future and, for all that they had loved and discovered in the night, still shy of each other.

Instead, Madrigal reached up for the charm she wore around her neck. “Do you know what this is?” she asked him, untying the cord.

“A bone?”

“Well, yes. It’s a wishbone. You hook your finger around the spur, like this, and we each make a wish and pull. Whoever gets the bigger piece gets their wish.”

“Magic?” Akiva asked, sitting up. “What bird does this come from, that its bones make magic?”

“Oh, it’s not magic. The wishes don’t really come true.”

“Then why do it?”

She shrugged. “Hope? Hope can be a powerful force. Maybe there’s no actual magic in it, but when you know what you hope for most and hold it like a light within you, you can make things happen, almost like magic.”

“And what do you hope for most?”

“You’re not supposed to tell. Come, wish with me.”

She held up the wishbone.

It was part whimsy and part impudence that had made her put the thing on a cord. She had been fourteen, four years in Brimstone’s service, but also now in battle training and feeling full of her own power. She’d come into the shop one afternoon while Twiga was plucking newly minted lucknows from their molds, and she had wheedled for one.

Brimstone had not yet educated her about the harsh reality of magic and the pain tithe, and she still regarded wishing as fun. When he refused her—as he always did, not counting scuppies, which cost a mere pinch of pain to create—she’d had a small, dramatic meltdown in the corner. She couldn’t even remember now what wish had been of such dire importance to her fourteen-year-old self, but she well remembered Issa extracting a bone from the remains of the evening meal—a grim-grouse in sauce—and comforting her with the human lore of the wishbone.

Issa had a wealth of human stories, and it was from her that Madrigal came by her fascination with that race and their world. In defiance of Brimstone, she took the bone and made an elaborate show of wishing on it.

“That’s it?” Brimstone asked, when he heard what petty desire had inspired her tantrum. “You would have wasted a wish on that?”

She and Issa were on the verge of breaking the bone between them, but they stopped.

“You’re not a fool, Madrigal,” Brimstone said. “If there’s something you want, pursue it. Hope has power. Don’t waste it on foolish things.”

“Fine,” she said, cupping the wishbone in her hand. “I’ll save it until my hope meets your high expectations.” She put it on a cord. For a few weeks she made a point of voicing ridiculous wishes aloud and pretending to ponder them.

“I wish I could taste with my feet like a butterfly.”

“I wish scorpion-mice could talk. I bet they know the best gossip.”

“I wish my hair was blue.”

But she never broke the bone. What started as childish defiance turned into something else. Weeks became months, and the longer she went without breaking the wishbone, the more important it seemed that when she did, the wish—the hope, rather—should be worthy of her.

In the requiem grove with Akiva, it finally was.

She formed her wish in her mind, looking him in the eyes, and pulled. The bone broke clean down the middle, and the pieces, when measured against each other, were of exactly the same length.

“Oh. I don’t know what that means. Maybe it means we both get our wishes.”

“Maybe it means that we wished for the same thing.”

Madrigal liked to think that it did. Her wish that first time was simple, focused, and passionate: that she would see him again. Believing she would was the only way she could bring herself to leave.

They rose from their crushed clothes. Madrigal had to wriggle back into the midnight gown like a serpent back into a shed skin. They went into the temple and drank water from the sacred spring that rose in a fount from the earth. She splashed her face with it, too, paid silent homage to Ellai to protect their secret, and vowed to bring candles when she came again.

Because of course she would come again.

Parting was almost like a stage drama, an exaggerated physical impossibility—to fly away and leave Akiva there—the difficulty of which she would not, before this moment, have believed. She kept turning and returning for one last kiss. Her lips, unaccustomed to such wear, felt mussed and obvious, carnal, and she imagined herself red with the evidence of how she had spent her night.

Finally she flew, trailing her mask by one of its long ribbon ties like a companion bird winging at her side, and the dawn-touched land rolled beneath her all the way back to Loramendi. The city lay quiet in the aftermath of celebration, pungent and hazy with the residue of fireworks. She went in by a secret passage to the underground cathedral. Its interlocking gates were keyed by Brimstone’s magic to open to her voice, and there was no guard to see her come in.

It was easy.

That first day she was hesitant, cautious, not knowing what had passed in her absence, or what wrath might await her. But the fates were weaving their unguessable threads, and a spy came that morning from the Mirea coast with news of seraph galleons on the move, so that Thiago was gone from Loramendi almost as soon as Madrigal returned to it.

Chiro asked her where she’d been and she gave a vague lie, and from then on her sister’s manner toward her changed. Madrigal would catch her watching her with a strange, flat affect, only to turn away and busy herself with something as if she hadn’t been watching her at all. She saw her less, too, in part because Madrigal was adrift in her new and secret world, and in part because Brimstone had need of her help in that time, and so she was excused from her other duties, such as they were. Her battalion was not mobilized in response to the seraph troop movements, and she thought, ironically, that she had Thiago to thank for it. She knew that he’d been keeping her from any potential danger that might relieve her of her “purity” before he had a chance to marry her. He must not have had time to countermand the orders before his departure.

So Madrigal spent her days in the shop and cathedral with Brimstone, stringing teeth and conjuring bodies, and she spent her nights—as many as she could—with Akiva.

She brought candles for Ellai, and cones of frangible, the moon’s favorite spice, and she smuggled out food fit for lovers, which they ate with their fingers after love. Honey sweets and sin berries, and roasted birds for their ravenous appetites, and always they remembered to take the wishbone from its place in the bird’s breast. She brought wine in slender bottles, and tiny cups carved from quartz to sip it from, which they rinsed in the sacred spring and stored in the temple altar for the next time.

Over each wishbone, at each parting, they hoped for a next time.

Madrigal often thought, as she sat quietly working in Brimstone’s presence, that he knew what she was doing. His gold-green gaze would rest on her, and she would feel pierced, exposed, and tell herself that she couldn’t go on as she was, that it was madness and she had to end it. Once she even rehearsed what she was going to say to Akiva as she flew to the requiem grove, but as soon as she saw him it went out of her mind, and she slipped without struggle into the luxury of joy, in the place they had come to think of as the world from her story—the paradise waiting for lovers to fill it with happiness.

And they did fill it. For a month of stolen nights and the occasional sun-drenched afternoon when Madrigal could get away from Loramendi by day, they cupped their wings around their happiness and called it a world, though they both knew it was not a world, only a hiding place, which is a very different thing.

After they had come together a handful of times and begun to learn each other in earnest, with the hunger of lovers to know everything—in talk and in touch, every memory and thought, every musk and murmur—when all shyness had left them, they admitted the future: that it existed, that they couldn’t pretend it didn’t. They both knew this wasn’t a life, especially for Akiva, who saw no one but Madrigal and spent his days sleeping like the evangelines and longing for night.

Akiva confessed that he was the emperor’s bastard, one of a legion bred to kill, and he told her of the day the guards had come into the harem to take him from his mother. How she had turned away and let them, as if he wasn’t her child at all, but only a tithe she had to pay. How he hated his father for breeding children to the task of death, and in flashes she could see that he blamed himself, too, for being one of them.

Madrigal smoothed the raised scars on his knuckles and imagined the chimaera represented by each line. She wondered how many of their souls had been gleaned, and how many lost.

She did not tell Akiva the secret of resurrection. When he asked why she bore no eye tattoos on her palms, she invented a lie. She couldn’t tell him about revenants. It was too great a thing, too dire, the very fate of her race balanced upon it, and she couldn’t share it, not even to assuage his guilt for all the chimaera he had killed. Instead, she kissed his marks and told him, “War is all we’ve been taught, but there are other ways to live. We can find them, Akiva. We can invent them. This is the beginning, here.” She touched his chest and felt a rush of love for the heart that moved his blood, for his smooth skin and his scars and his unsoldierly tenderness. She took his hand and pressed it to her breast and said, “We are the beginning.”

They began to believe that they could be.

Akiva told her that, in the two years since Bullfinch, he had not slain another chimaera.

“Is it true?” she asked, hardly believing it.

“You showed me that one might choose not to kill.”

Madrigal looked down at her hands and confessed, “But I have killed seraphim since that day,” and Akiva took her chin and tilted her face up to his.

“But in saving me, you changed me, and here we are because of that moment. Before, could you have thought it possible?”

She shook her head.

“Don’t you think others could be changed, too?”

“Some,” she said, thinking of her comrades, friends. The White Wolf. “Not all.”

“Some, and then more.”

Some, and then more. Madrigal nodded, and together they imagined a different life, not just for themselves, but for all the races of Eretz. And in that month that they hid and loved, dreamed and planned, they believed that this, too, was meant: that they were the blossoms set forth by some great and mysterious intention. Whether it was Nitid or the godstars or something else altogether, they didn’t know, only that a powerful will was alive in them, to bring peace to their world.

When they broke their wishbones now, that was what they hoped for. They knew they couldn’t hide in the requiem grove and daydream forever. There was work to be done; they were just beginning to make it real, with such passion in their hope that they might have wrought miracles—begun something—had they not been betrayed.