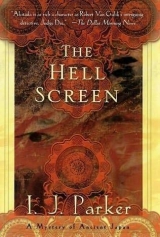

Текст книги "The Hell Screen"

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

“Never mind,” said Eikan. “This is a special situation. You know His Reverence has told us to cooperate fully with the authorities.”

Seeing the young man’s uneasiness, Akitada said soothingly, “I will be as quick as I can. I am sure you must find all this upsetting.”

Ancho nodded gratefully. He looked like a bright youngster, not much more than eighteen, Akitada guessed.

“Well, then, Ancho, are you certain that the door to this room was locked when you came to clean the room?”

“Yes. When there was no answer to my knocking, I pushed against it. Usually the guests leave the door unlatched when they leave. I knocked again, and when there was again no answer, I inserted my key and tripped the latch.”

“May I see the key, please?”

Ancho exchanged a glance with Eikan—who nodded firmly—and handed over a thin metal gadget he carried tied to the rope around his waist.

The key was peculiarly shaped, and Akitada saw immediately that it was made especially for this kind of latch. He inserted it into the hole and heard the small click as the latch moved. A slight twist released it again. Satisfied that only an expert thief, and one who had come prepared, would be able to unlock the door without this special key, Akitada returned it to the young monk.

“Now I must ask about some things which you may find upsetting,” he said. “Please forgive me and do the best you can. First, tell me exactly what you saw when the door opened.”

The young monk closed his eyes. He grew a bit paler, but spoke readily enough. “I saw the lady on the floor. Her feet were toward the door. I recognized the robe right away. Very pretty it was, with chrysanthemums and golden grasses embroidered on it. I thought she was asleep, but she was not on her bedding. She was on the bare floor and lying strangely. Then I thought she had become ill and fainted. I went in to help her.” He shuddered and swallowed hard. “There was blood and her face… there was no face… it was all cut up. I knew she was dead then and I ran.” He opened his eyes and looked at Akitada miserably.

“You are doing very well,” said Akitada reassuringly. “Were you at all aware that there was someone else in the room?”

Ancho shook his head. “There wasn’t much light, only what came from the open door, and I only looked at the lady, never thinking that a man might have joined her.” He flushed painfully and averted his eyes.

“You said you recognized her robe. Had you seen her the night before?”

“Yes, my lord. When I brought her bedding and some food and water.”

Eikan cried, “You had served her? You never told me.”

Ancho said simply, “You never asked me.”

For a moment Eikan looked irritated, then he brightened. “How about that? Only someone like you, my lord, would discover such a very important fact from a casual word. I have much to learn, it seems.”

Akitada’s mouth twitched. “Do you expect to need such skills in your way of life?”

“Certainly, my lord. You’d be surprised at the sorts of tricks our youngsters get up to, though not murder, of course. Also, with so many visitors, and low types like those actors … though I believe the abbot plans to review the policy of permitting acting groups and women to stay here. It is written: All degeneration of the Law begins with women.’ “

“I confess I was startled that the temple admits lay women free access to the monastery. I found some of the actors, men and a woman, in the bathhouse that night.”

Eikan looked profoundly shocked. “A woman? Are you certain, my lord? That area is strictly forbidden to lay persons of either gender. What about the bath attendant?”

“He went to speak to them, but with little effect. I thought perhaps the rules had been lifted for the occasion of the festival.”

“Not at all, my lord. The actors were supposed to remain in their rooms here.” He shook his head. “No wonder the abbot is upset.”

Akitada turned back to Ancho.

“Tell me about the evening before, when you saw the two people alive.”

“They sent me to serve new guests, a gentleman and a lady. I stopped first in the kitchen. It was closed already, but I put cold rice cakes and two pitchers of water into a basket. These I took to the veranda before the lady’s room. Then I fetched a roll of bedding from the storeroom and knocked. The lady opened the door. I tried not to look at her, but noticed the pretty gown. I took in the bedding first and put it under the window.” He flushed. “We are not supposed to spread it out. As soon as I had done that, I went back for some of the rice cakes and a pitcher of water. I put those just inside the door and went to do the same for the gentleman.”

“I see. You did not speak with either of the guests?”

“No, my lord. It is discouraged. The gentleman thanked me.”

“Did you notice any luggage?”

“Yes, my lord. The gentleman had a saddlebag and his sword, and the lady had just a saddlebag.”

“How did they seem? Cheerful, nervous, bored, or irritated?”

“It is hard to say. The gentleman gave me a smile and a nod. He looked tired, I think. The lady was walking about. Perhaps she was nervous. I don’t know. She did not smile, and did not so much as look at me. I’m afraid that is all I can tell.”

Somewhere a bell began to ring again, high and strident. Ancho glanced over his shoulder and began to inch away.

“The bell for our noon meal, my lord,” said Eikan.

“Just a moment more,” said Akitada. “As you were on duty that evening, did you have occasion to serve another visitor who would have arrived later? He would have been in his fifties, gray-haired and thin.”

“Oh, no, sir. There were no other visitors later that night. And I don’t recall seeing anyone like the man you describe.”

So Nagaoka apparently had not followed his wife and brother. “One more thing: did any of the other guests express an interest in the lady who died?”

Ancho shook his head. “Not to my knowledge, sir.”

“Thank you. That is all. It was very good of you to think back to something which must have troubled you a great deal.”

Ancho bowed briefly and then ran. Eikan lingered behind, watching as Akitada pulled the door to the murder room shut behind him and found that it would not latch. “There is no need to lock it, my lord,” he said.

Akitada stared at the door fixedly. Then he pulled it to again, harder this time. The latch jumped into place with a loud click and the door was locked.

“It locks from the outside,” Akitada said with pleased surprise. “And that explains why Ancho and his fellow attendant have keys and why he opened the locked door with the key after knocking. He assumed it was empty and had slammed shut.”

“Of course. People sometimes slam the doors so hard that they lock by themselves.”

“But that makes all the difference,” said Akitada. “While no one could enter a locked room without a key, it was quite simple to leave a room locked. Thanks to your help, we now know that someone other than Kojiro could have killed Mrs. Nagaoka.”

Eikan looked blank. After a moment he said, “I am not sure I understand. May I ask if my lord suspects one of us?”

“Not necessarily. Someone who was in the temple or monastery the night of the murder. There were, by all accounts, many outsiders here that night. But you will miss your meal and I must continue my journey. I shall not forget your generous and invaluable assistance.”

Eikan brightened slightly. “I have time. Someone brings my food to the gate. Will you come back, my lord?”

“Perhaps. But whatever happens, I shall let you know the outcome.”

They parted company pleased with each other, and Akitada mounted his horse again and hurried back down the mountain road, anxious to make up for lost time.

Not completely lost, perhaps, for he had at least enough information now to speak again to Kobe. But there were so many uncertainties, not the least of which was the troubling person of Noami. The man seemed to be everywhere, a perpetual, ominous presence in the background.

He fell imperceptibly into glum discouragement again as he reviewed the past weeks. He was no closer to the solution of the murder of Nagaoka’s wife, at home his unforgiving mother lay dying, one of his sisters was desperately unhappy and the other had married a man under suspicion of theft from the Imperial Treasury, he himself had yet to make his report to the palace, and he had so far failed to solve even one problem.

The mood persisted until he passed through a clearing and caught a glimpse of the valley and the highway below him. At the little shack where he had stopped earlier he saw a great bustle of carts, horses, and people. A group of travelers had paused on their journey to the capital.

His eyes sharpened, and he counted. Yes, two carts with oxen and a number of horses, at least fifteen. And there, just inside the shack, he saw the blue robe of a woman, and then a man stepped out, carrying a small child on his back. They had finally come!

Giving a shout of joy, Akitada slapped his horse into a neck-breaking gallop down the road to greet his family.

NINE

Family Matters

Their reception at the house was less than climactic. To be sure, Saburo grinned hugely when he saw his mistress again, and Yoshiko came running, brushing at her cotton gown and smoothing her hair back, but the other servants were strangers and merely peered curiously into the courtyard filled with horses, wagons, and strange men. But with the elder Lady Sugawara at death’s door, and the chanting of the monks casting a pall over the return, there was no sense of celebration.

Tamako and Yori looked well after their long journey, healthy and tanned by the sun. Yoshiko’s sickly pallor was all the more apparent by contrast.

Tamako knew about his mother’s condition from Akitada, but now asked Yoshiko for the particulars. The two women, Yoshiko with Yori in her arms, walked toward the elder Lady Sugawara’s room, while Akitada followed glumly behind. He had felt a strong urge to prevent this meeting, to protect them from the poison of his mother’s disturbed mind, but Tamako had quickly informed him that it was her duty as daughter-in-law to pay her respects and present her son. So he hung back, stopping outside the door among the chanting monks, while the women disappeared inside.

He had a long wait, which he passed in morose thought, staring down at six shaven heads and thinking of the mountain temple; the murder; the painter Noami, once a monk himself; the hell screen; and finally of his gift for Tamako. The last thought cheered him, for presenting the scroll of boy and puppies reminded him that he would soon be alone with his wife. They would have a chance to talk, make plans for the future, touch hands, and then perhaps make love.

When Tamako emerged from his mother’s room, her face drawn with distress, she was surprised to find her husband smiling at her happily, his hands extended eagerly.

“Finally,” he cried. “Come, let us go to my room. I have missed you dreadfully.”

One of the monks choked over a line, causing the chant to disintegrate and falter into silence. Six pairs of reproachful eyes were raised to Akitada. Then the oldest monk nearest the door cleared his throat and raised a hand. At his signal, they all picked up the chant again and continued.

Tamako took Akitada’s extended hand and drew him away quickly. “She is dying,” she murmured, partly in reproach and partly to express her own sadness. When they had put some distance between themselves and the monks, she added, “It cannot be long now. But she knew me, and she raised a hand to caress Yori. Only she was too weak even for that. Oh, Akitada! We returned barely in time.”

Akitada looked into his wife’s tear-filled eyes and marveled at her grief for a woman she had barely known. He knew his mother to be undeserving of such kindness. “I returned too soon,” he said harshly. “If I had taken my time, it would have saved me the knowledge that my own mother hated me enough to drive me from her presence with curses.”

“Oh, Akitada!” Tamako looked deeply distressed. “You did not tell me.”

He turned away and started walking toward his room. “I did not mean to poison your mind, too,” he said. “I stay away from her, waiting for the end, hoping it will come soon and release all of us so we can begin to live our lives like everyone else.”

He opened the door to his room. It was cold. No one had thought to bring a brazier or hot water for tea. Akiko’s luxurious quarters came to his mind, with their many glowing braziers, the silken bedding, and the cushions spread on thick straw mats and protected from drafts by screens and curtain stands.

“Forgive me,” he said, turning toward his wife. “Nothing is ready. My mind has been on other things. This is a dreadful homecoming for you.”

For all that, they rested well that night. The following morning, the bustle of settling in began. Akitada went early to inspect the stables and greet his horses. The weather was cold, windy, and overcast, causing him anxiety. A large portion of the stables was roofless, and cold currents of air stirred up the straw spread for the animals. He gave instructions to Genba and Tora about temporary weatherproofing and blamed himself for not having taken care of this before.

When he returned to his room, he found Tamako shivering under a winter robe. “I am sorry, my dear,” he said. “My mother’s illness keeps the servants busy. And here you are in a cold room with not so much as a hot cup of tea.” He suddenly missed his son. “Where is Yori?” he asked, glancing anxiously back toward the door.

Tamako smiled a little. “Don’t fret. Yoshiko has taken him to your mother again. She seems better when she looks at him, and he does not mind being around her. And do not worry about me. Now that I am here, I shall be able to give a hand to Yoshiko, who must have had a dreadful struggle taking care of your mother and you, too. She has only one housemaid to help her, she says.”

Akitada flushed guiltily, thinking of the robe his sister had sewn for him.

“I am worried about Yoshiko,” Tamako said, unpacking clothing and draping it over clothes racks to air out.

He grimaced. “I know. Too much work, my mother’s sharp tongue, her illness, loneliness! It has been no life for a young woman of her class. I promised to find a husband for her. With a home of her own, she will soon be her own self again.”

Tamako laughed. “Oh, Akitada! It is not that simple!” Turning serious, she said, “No. There is something else. Apparently she is keeping it to herself, and that means trouble of some sort.”

Akitada cocked his head and smiled at his wife. “You are just looking for someone to dose with one of your magic potions,” he said fondly. His wife’s skill with herbal remedies had been a great boon to his family and household during the long years in the north. Even Seimei, his old friend and a family retainer, had turned over his box of salves and teas to her and concentrated instead on his new role as Akitada’s personal secretary. “It is enough that we have my mother’s illness to deal with,” he said firmly. “Yoshiko is quite well, just tired and housebound.”

Tamako went to open the shuttered doors to the overgrown garden. Cold air blew into the already chilly room. “Your mother is beyond my help.” She sighed, looking at the sad tangle of shrubs and trees.

Akitada had followed her to the door. “I have not had time to get things tidied up,” he said apologetically. The evergreen shrubs had grown to tree height, and frost-blackened weeds and choking piles of dead leaves and fallen branches covered everything else.

But Tamako smiled. “Never mind! I have always liked this room best. It gets sunlight most of the day and yet the garden is like a private world. It will be good to garden again. No more long winters and crushing snows. We shall sit on this veranda and sip tea, admiring the azaleas and camellias, peonies, and autumn chrysanthemums.” She turned to him impulsively, her eyes shining. “Oh, Akitada! It is good to be home.”

Akitada was so deeply touched by his wife’s words that he did not realize for a moment that he was about to lose the room he had always occupied, the place where he had slept and worked and found refuge from the disdainful eyes and words of his parents. Well, he would find another room if Tamako wanted this one. “You know,” he said, pulling her against him, “I was never happy in this house until now.”

Instead of answering, Tamako buried her face against his shoulder with a happy sigh. Outside, a breeze picked up a handful of brown leaves and whirled them into the air. He shivered and wrapped his arms more tightly around her. “It has turned winter early,” he said. “And there is no heat in this room. You must be cold. I wonder what happened to the servants. I have not had time to see about hiring more staff, either. Let me go get your maid and see about some tea and braziers.”

She chuckled and released him reluctantly. “It does not matter, though a cup of hot tea would be nice.”

He closed the veranda doors and went in search of the maid. Except for the distant chanting of the monks, the house seemed deserted, it was so quiet. When he went outside, he saw that the carts still stood in the courtyard only half unloaded.

In the low kitchen building he found the cook and his mother’s tall rawboned maid in eager conversation with Tamako’s dainty maidservant, satisfying their curiosity about the new mistress and Akitada’s people. Apart from a bit of a small fire under the rice steamer and a small pile of chopped vegetables on a board, there was no sign of food preparation.

Feeling more than ever that this negligence was his fault, he snapped, “Why are there no braziers in my room? And where is the hot water for tea?”

The cook and the big housemaid rushed toward the stove and the empty braziers.

Akitada glared at Tamako’s pert little maid and growled, “You are a terrible gossip, Oyuki. Go to your mistress immediately to make her comfortable!” The girl rose, grinning impudently, and disappeared.

The cook was pouring boiling water into a teapot, and the housemaid transferred glowing charcoal from the hearth to one of the braziers.

“When you have taken that brazier,” Akitada ordered, “come back for another. The room is very cold.”

The maid goggled at him. “I can’t. The old mistress won’t allow more than one brazier, sir,” she protested.

“I am the master here now,” Akitada corrected her with a flash of anger, “and from now on you do what I say, or what my wife tells you to do. Do you understand?” He directed a quelling glance at the gaping cook and added, “Both of you.” Then he extended his hand for the teapot. “Get busy with the morning rice,” he told the cook. “There are many mouths to feed.”

The cook wailed, “There’s not enough food for the rest of the day.”

He almost cursed. But it was not, after all, the woman’s fault. “Get more and do the best you can!”

Carrying the pot of hot water, he preceded the big maid with her brazier to his room, where he found Tamako admiring Noami’s scroll painting and her maidservant unpacking a clothes box someone had brought in. Piles of gowns lay strewn about the room, and mirrors and cosmetics cases covered his desk. He sighed inwardly, but said only, “The scroll is a present for you. Do you like it?”

“It’s beautiful,” she said. “I don’t think I have ever seen anything so lifelike. You can see every whisker on the puppies and every hair in their tails, and the little boy is charming. Wherever did you find this?”

The maid had placed the brazier next to his desk and left. Akitada poured hot water and brought Tamako her cup of tea. “Akiko’s husband Toshikage found the artist. He commissioned a screen for her room. When I saw the screen, I knew I wanted you to have one, too, but the painter is a very strange creature, not at all pleasant even if he is very skilled. He insisted that he would have to observe the flowers for a whole year to paint a screen of plants for all seasons.”

“How odd! I would like to meet the man sometime. How is Akiko? Yoshiko told me she is expecting a child.”

“Yes. She seems in excellent health and very happy.” He decided not to mention Toshikage’s troubles and said only, “I like her husband, and he seems to dote on her.”

Tamako studied his face. “Good! I shall look forward to meeting him.”

The door opened, admitting Tora and Genba with more boxes. When they had gone, the second brazier appeared.

Akitada put down his empty cup. “There is much to do. I forgot to let Akiko know about your arrival. And I suppose I had better speak to Seimei about finding me other accommodations. And then I will lend a hand to the stable repairs. The place is not in good condition, I am afraid.”

Tamako smiled at him. “Never mind! It will all come right now.”

Akitada encountered Seimei in the hallway leading to his father’s room. The elderly man was lugging a heavy box of documents.

“Wait,” cried Akitada, rushing up to relieve him of the load. “You should not be doing this,” he scolded. “It is much too heavy. Tora or Genba can carry the boxes and trunks. Where are you going with it?” He recognized his own writing set and personal seals among the items in the box.

“To your father’s room,” said Seimei. “It is fitting that you should be there now.”

Akitada stopped abruptly. “No! Not there!”

Seimei looked up at him, his eyes sympathetic in the heavily lined face. “Ah! Old wounds are painful.”

“You should know better than anyone,” Akitada said harshly, “why I cannot work in a room filled with such memories.”

The old man sighed. “You are the master now. And your father’s room is the largest and best room in the house. It is expected that you should occupy it.”

The thought crossed Akitada’s mind that Tamako had assumed the same thing, but he simply could not face the prospect. “Some other room will do for the time being. Until we get my father’s things cleaned out,” he promised lamely.

“They have been put away already,” Seimei informed him, and headed down the corridor. “There will be talk if you do not assume your father’s position in this house. A man does not forget what is owed to either his home, his family, or himself.”

His master followed dazedly with the box. When Seimei flung back the lacquered doors to his father’s study, Akitada made one last desperate appeal. “My father did his best to prevent my taking his place. No doubt he will haunt this room if I use it.”

At this Seimei chuckled. “Now you sound like Tora. I do not believe you. In any case, remember that patience is bitter, but its fruit is sweet. I have dreamed for many years of this day, hoping to live long enough to see you installed in your father’s place.”

Akitada looked at Seimei in astonishment. The old man had been with him all his life, doing his best to protect the child and youngster against his father’s anger and his mother’s resentment, but he had done so without ever committing the offense of criticizing, either. His loyalty to the Sugawara family had been exceeded only by his love for young Akitada. Akitada was more deeply touched than he cared to admit and gave up his resistance.

“Oh, very well,” he said, and lugged the box into the room. Then he looked around. The light was dim, with the doors to the garden closed against the weather. The air smelled stale and musty.

There were the familiar shelves against one wall, but his father’s books and document boxes were gone. Gone also were the calligraphy scrolls with the Chinese cautionary precepts and the terrifying painting of Emma, the king of the underworld, judging the souls of the dead. This picture in particular had always instilled a special terror in young Akitada when he had crept into his father’s room, expecting punishment. The resemblance between his father and the scowling judge had been striking, and Akitada had always suspected that that was the reason the painting held such a prominent place in the room.

The broad black-lacquered desk was also bare of his father’s writing utensils and his special brazier and lamp. Only the atmosphere of stern and unforgiving judgment lingered. Akitada shuddered at the thought of receiving his own son in this room.

Seimei opened the doors to the veranda. Fresh, cold air came in. There was a private garden outside, with a narrow path leading to a fishpond, now covered with floating leaves. As a boy, Akitada had never been allowed to play here. Seimei tut-tutted at the state of the shrubbery, but Akitada stepped outside, glad to escape the room, and went to peer into the black water of the pond. Down in the depths he could make out some large glistening shapes, moving sullenly in the cold water. He picked up a small stick and tossed it in, and one by one the koi rose to the surface looking for food. They were red, gold, and silver, spotted and plain, and they looked up at their visitor curiously. Yori would like this place.

“Perhaps,” said Akitada, “with some changes, the room might do.”

Seimei, who had waited on the veranda, watching his master anxiously, gave a sigh of relief. “Her ladyship has directed which screens, cushions, and hangings are to be brought here. And, of course, there will be your own brushes and your books, your mementos from the north country, your tea things, your mirror and clothes rack, and your sword.”

“Hmm. Yes. Well, make sure your own desk is placed near mine,” said Akitada, giving the old man a fond smile, “for I refuse to work here without you.”

Seimei bowed. “It shall be so” There was a suspicion of moisture in his eyes as he turned to go back into the room.

Akitada followed, saying with a pretense of briskness, “I must go see about the horses and will send Tora to you. But could you dispatch a message to my brother-in-law Toshikage’s, letting them know that the family has arrived?”

“I took the liberty to do this earlier, sir.”

“I should have known.” Akitada touched the old man’s shoulder with affection, painfully aware how frail it had become. “I shall always think of you as my real father, Seimei,” he said, tears rising to his own eyes.

Seimei looked up at him. His lips moved, but no words came. Instead he touched Akitada’s hand on his shoulder with his own.

It was not until the afternoon that Akitada was free to help with the stables. A good part of the building had been torn down years ago, when he was a child. The Sugawara finances had made the keeping of horses and oxen impractical when there were neither grooms for their care nor money for their fodder. Since then a part of the remaining section had lost its roof, and piles of wet leaves covered the rotten boards where once horses had stood.

He found Tora and Genba busy erecting a rough wall between the roofed area and the stalls that were open to the elements. In this freezing weather, you could not leave animals unprotected. Akitada’s four horses and the pair of oxen which had drawn the carts were crammed together in the most sheltered part, where they had dry flooring covered with fresh straw.

The big gray stallion, a gift from a grateful lord, turned its handsome head to look at Akitada and whinnied. He went to the animal, running his hands over its body and down the slender, muscular legs, then did the same with the other three, a bay and two dark brown geldings. They had made the long journey in good condition. The bay was smaller than the others, but finely made and belonged to Tamako. They would be able to take rides into the countryside together. And soon, he thought contentedly, he would have to buy a horse for his son.

Protecting his horses was more important to Akitada than arranging his books. He worked companionably with his two retainers. Genba, a very big man, broad-shouldered and heavily muscled, had once been a wrestler. It was a sport he still engaged in at odd times, but he had, with great difficulty, lost much of the weight he used to carry and was perpetually hungry or fantasizing about foods.

Tora was willing enough to put his hand to a bit of rough carpentry when there were no pretty young women around to distract him. He had joined the household during Akitada’s first assignment, when his master had taken a chance on the ex-soldier and saved him from a murder charge.

It got much colder when darkness fell, but the efforts of lugging about boards and climbing up and down ladders kept them warm enough, and the exchange of news passed the time.

Genba and Tora listened spellbound to his account of the events at the mountain temple. But when Akitada spoke of the hell screen and the painter’s studio near the Temple of Boundless Mercy, Tora stopped hammering nails and stared at him.

“That place is haunted!” he announced. “Hungry ghosts are thick as flies there and every morning the outcaste sweepers find parts of human bodies.”

Working side by side in the flickering light of torches while the animals quietly munched their hay and moved about in the straw went a long way toward laying the ghosts haunting Akitada’s mind. Tora’s imaginings were so far-fetched that both Akitada and Genba laughed at some of the details.

“Not a bad job,” remarked Genba when they were done, and had looked over the makeshift wall. “I think I’ve earned an extra helping of the evening rice. I meant to ask you, sir, how’s the cook? Not too stingy with fish in her soups and stews, is she?”

“She is from the country and cooks hearty meals, but you were not expected. There may not be enough food in the house.”

Comically, Genba’s face first fell, then brightened again. “I could run out and get some of those vegetable-stuffed dumplings, and maybe some soba noodles. Yori likes those.”

Akitada was putting on his robe. “Very well,” he said with a smile. “But don’t buy more than we can eat.”

Tora hooted. “That’s like telling the cat not to eat the fish.” As Genba headed out the door grinning, Tora turned to Akitada. “I’m ready to get started on that temple murder tomorrow.”

Akitada had planned to speak to Kobe as soon as possible, but now there were other things to be done. It would have to wait. He told Tora, “First we must get the family settled.”

Tora waved a dismissive hand as they headed out of the stable. “Done in no time!”