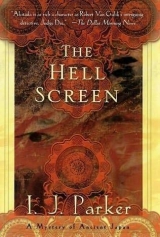

Текст книги "The Hell Screen"

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

With Tora’s fingers gripping his painfully, Akitada said, “Put on the ice! In her business the woman should know what works best.”

The monk grunted. “The love of women leads to delusion. Don’t have any leeches anyway,” and transferred the ice to a square of cotton, which he tied and placed on the injured groin. Tora sighed and relaxed a little.

Next the old monk fingered the purple bruises on Tora’s chest. “No broken ribs,” he pronounced, “but some of the vital organs may have been displaced or injured. The patient’s coldness and the sweating suggest a rupture may have occurred, but it is too soon to tell.”

“What if there is a rupture?” asked Akitada, visions of Tora’s slow and agonizing death from internal injuries passing through his mind.

But the monk knotted up his bundle and rose, saying piously, “We must all prepare to leave this world of nothingness.”

A miserable silence settled over the room after the monk had left. Then Tora said tentatively, “The ice helps.”

“Good,” cried Kobe. “You see! All will be well.”

“What about your breathing?” asked Akitada.

“The same.” Tora looked up at him. “I’m not afraid to die.”

“You are not going to die,” cried Akitada, and jumped up. “Where is that oxcart? You are going home, where Seimei will make you well.”

The door opened. Miss Plumblossom said, “There’s a messenger outside for you, Superintendent.”

Kobe left the room, and Miss Plumblossom inched in. She had been weeping, for black smudges ringed her eyes like a badger’s. “I’m very sorry, Tora,” she told the patient. “I’ll try to make it up to you. Whatever I have, it’s yours.”

Tora waved a languid hand. “Forget it!”

“No, no,” she insisted, wringing her hands, when Kobe put in his head again.

“The oxcart is ready. But I have to leave. Looks like they found Nagaoka. Dead. His skull bashed in.”

SEVENTEEN

Switched Boots

Since Kobe had rushed off without giving particulars about Nagaoka’s death, Akitada merely saw Tora settled under Seimei’s care before he went looking for the superintendent. Unfortunately, at his headquarters nobody knew or wanted to tell him where he had gone. He met with the same results at the prison, but here Akitada fretted and complained, and finally demanded to see Kojiro. The officer in charge relented and took him to the cell.

Kojiro rose as soon as Akitada entered. He looked much better than the last time they had met. Apparently there had been no further beatings, and he had been allowed to wash and shave. When he recognized his visitor, he bowed, his eyes intent. “Is there news, my lord? Have they found Nobuko’s murderer?”

Evidently Kobe had not bothered to inform the man of his brother’s death. Akitada steeled himself for the ordeal. “There is news, but it does not concern your sister-in-law.” He searched for the right words. “I was hoping,” he finally confessed, “that the superintendent had told you. He received an unsubstantiated report that your brother has met with a mishap.”

Instant anxiety appeared in the other man’s eyes. “Mishap? What kind of mishap? Is he wounded? Ill?”

“I have no details, nor do I know where he was found.”

“ ‘He was found’? Then it must be serious.” Kojiro clenched his manacled fists and glared at the locked cell door. Frustrated, he started pacing back and forth. The chain on his legs clinked and limited his path to no more than three steps either way. Like a caged beast, he had learned when to turn. “He may even be dead,” he muttered, then stopped. “Is he dead?”

Akitada spread his hands helplessly. “There is a chance that the man they found is not your brother after all,” he evaded awkwardly.

“But they found a dead man and think he’s my brother?”

Akitada nodded.

Kojiro sat down abruptly and put his head in his hands. After a moment he said dully, “Thank you for telling me. This way I shall be prepared when Kobe finally bothers to inform me.”

“This is bad news, and I am very sorry to be the one to bring it.” Akitada crouched down near him. “A number of strange things have been happening. Perhaps they have something to do with the death of your sister-in-law, and if the man they found is indeed your brother and he was murdered also, the same killer may be responsible. The best thing you can do now is to help me find justice for both. Can you explain why your brother might sell all his goods, everything except the house? And why he would then disappear without telling anyone where he was going or why?”

Kojiro raised his head from his hands and looked at him bleakly. “Perhaps, but I doubt it has anything to do with Nobuko’s death. My brother’s business affairs have not been going well for a few years now. I offered money on a number of occasions, but he always refused it. Too much pride. His reputation was excellent, and his creditors did not press him for payment as a rule, but perhaps this time their patience ran out. Paying his debts is a matter of conscience with him. He would do so even if it meant selling everything. My brother had much honor.” Tears welled up in his eyes, but he controlled himself immediately. “Could he have been killed because he carried the money on him?”

“Possibly. His servant said he left with a saddlebag, and was dressed for a journey. He may have rented a horse. Did he have any creditors outside the capital?”

“Yes. He sometimes bought art objects from temples and from country manors. I’m afraid he kept business details to himself, perhaps because he did not want me to help him out.”

“The last time I was here, I asked you to think about your sister-in-law.”

Kojiro rubbed his face as if to remind himself of his own problems. “I don’t know what you have heard, so I had better tell you what I saw and thought of her.” He told about his encounters with Nobuko, from their first meeting to the calamitous trip to the temple. He described her beauty and said he had distrusted her for marrying his middle-aged brother, but had accepted her when he saw his brother’s happiness and pride in his young wife’s talents.

“She could play the zither like a professional and knew wonderful songs. Sometimes she even danced for us. My brother was completely enchanted, and in time so was I. I was stunned, appalled, when she approached me one day to suggest we become lovers because my brother was … inadequate and she wanted a child. Torn between disgust and pity, I stopped my visits to my brother’s house. But he sent for me and I went back reluctantly. To my relief, my sister-in-law was cold and distant. I assumed she was embarrassed about the incident.”

“Could she have been angry with you for rejecting her advances?”

Kojiro nodded. “She may have been. At the time I said some things to her that I regret now, but I meant to shock her into having more sense.”

“Do you think she could have found another lover?”

He shook his head. “I have wondered, but don’t see how. My brother never entertained, and the only men who came to his house were clients who never met his wife.”

“What about her life before her marriage? Were there any men in it?”

Kojiro shook his head helplessly. “I know only what she or my brother told me about her family life. Her father is a retired scholar. He moved to Kohata after his wife’s death. Nobuko was raised in the country, but she received a good education from her father. From what she said, I gathered that her life must have been entertaining. They had celebrations on all the festival days, sometimes with singers and musicians, and her father encouraged her to ride and took her with him on hunting trips. I always thought that she must be dreadfully bored in my brother’s house.”

Akitada pulled his earlobe and pondered. “Surely your brother showed her the famous sites of the capital? Or took her to the palace for horse races, and to temples for the festival dances and play performances?”

“No. My brother used to take an interest in theater in his younger years, but lately he considered public entertainments unsuitable for a man in his position and he would never have taken his wife. I thought she had settled for children and a quiet family life.” He flushed a little.

“There were some actors staying at the temple where she died. Uemon’s Players, they called themselves. It may not mean anything, but I knew of your brother’s interest and now you tell me your sister-in-law also may have met such performers.”

Kojiro looked blank. “I did not see them and know nothing of this.”

In the hallway outside the cell, steps and voices approached, followed by the grating of a key in the door. It opened and Kobe stepped in. Kojiro rose, his mouth set and his face expressionless.

Kobe nodded to him and turned to Akitada. “They told me you were here. Does Kojiro know?”

“I only told him what I knew. Was the report correct?”

“Yes, I’m afraid so. Sorry, Kojiro. Your brother was found bludgeoned to death near the southern highway. You have my sympathy.”

The prisoner looked down at his shackled hands. They were clenched so tightly that the knuckles showed white against the sun-darkened skin. “Thank you, Superintendent,” he said tonelessly. “I can only hope it was not my arrest and imprisonment which caused my poor brother to undertake this tragic journey.” He grimaced, then looked up at Kobe. “I don’t suppose you would let me out to find the bastards who killed him?”

“You know I cannot do that. There is still a murder charge against you.”

Akitada said, “All the evidence we have points away from Kojiro and to someone else. Now that Nagaoka himself has been killed—and Kojiro certainly could not have done that—is it not likely that the two murders are connected?”

“Why? From all accounts, the man carried money, which has disappeared. He must have been set on by bandits.”

Akitada sighed and rose. It was all too likely. “How is it that you are back so early?” he asked.

“I met my sergeant at the city gate. He was bringing back the body. I suppose you would like to see it for yourself ?”

“Yes.” Akitada turned to Kojiro. “I promise to do my best to find who is responsible for this. I liked your brother, you know. His knowledge of the antique trade was admirable, and he had great affection for you.”

Kojiro struggled to his feet. “I know. Thank you,” he said with a bow.

Akitada and Kobe crossed the prison courtyard to the same small building which had held the corpse of Nagaoka’s wife only a month earlier.

Nagaoka lay in much the same spot. He, too, had suffered dreadful wounds to the head, but his thin, sharp features were untouched and looked strangely noble in death. He wore the clothes the servant had described, but there was something odd about the way the body lay, and Akitada stared for a moment before he realized what bothered him.

“Are his legs broken?”

Kobe looked, then bent to manipulate one of them. “No.”

Behind them the door opened, admitting Dr. Masayoshi, the coroner.

“A new case?” He came forward and stared at Akitada. “You again? Do you make a habit of visiting the dead?”

“And a good day to you, Doctor.” Akitada made him a tiny bow, which the coroner returned in the same deliberately rude manner. Akitada pointed. “What is wrong with this man’s feet?”

Masayoshi looked at the corpse, briefly felt one of the legs, then grinned. “Your little joke, my lord? Forgive me, but it was rather puerile even for you.”

Akitada stared, then flushed at the insult. Controlling his fury with an effort, he walked to the body and jerked off one of the boots. Nothing at all was wrong with Nagaoka’s leg. His boots had been put on the wrong feet. Akitada’s eyes flew to Masayoshi’s face and caught the moment the coroner realized that it had not been a joke after all, but a mistake. Masayoshi’s eyebrows rose mockingly.

Akitada was tempted to wipe the sneer off the man’s face, but he clenched his fists and turned his back abruptly on the grinning coroner. He told Kobe, “Did your men do this?”

But they had not, and it changed everything. Even Kobe could not see bandits taking off their victim’s boots and then replacing them.

Kobe scratched his head. He removed the other boot and looked at Nagaoka’s feet. They wore clean white socks. “Strange!” he muttered. “I thought they might have tortured him. Maybe they tried on his boots and they didn’t fit.”

“Nonsense! They would not have bothered to put them back.”

Masayoshi had knelt to examine the head wound, probing it gently with his fingers. He was pursing his lips. Moving forward, he lifted the dead man’s eyelids and then smelled his mouth. He got to his feet with a satisfied grunt. “Even stranger than the boots,” he said, “is the fact that this man died from poison.”

“Poison!” yelled Kobe. “How poison? Even an idiot can see he’s been clubbed to death. Why poison him, too? Are you mad?”

Grinning, Masayoshi folded his arms across his small paunch and rocked back and forth on his heels. “Not at all.” He chuckled. “I must say, you present me with the most interesting cases, Superintendent,” he said appreciatively. “But actually you got it backward. He was poisoned first and clubbed afterward. You notice that there is very little blood in the wound. Dead men don’t bleed, you see.”

Silence greeted his explanation.

Much as he detested Masayoshi’s manner, Akitada did not question his professional expertise. In fact, he should have seen the lack of blood himself. He asked brusquely, “Can you tell when he died? And how much later the head wounds were inflicted?”

Masayoshi became businesslike. He returned to the body, flexing its limbs and joints down to the fingers and toes, then pulled apart the clothing to study Nagaoka’s torso and poke his thin belly. Finally he pinched the skin in a few places. Straightening up, he said, “Hard to tell. Depends on whether he was left lying around outside or inside near a fire. He’s been frozen, of course, so he was outside at least part of the time and probably all of it. My guess would be several days. The head injury happened shortly after death, probably while the body was still slightly warm. There are some residual traces of bleeding in the wounds.”

“Several days! That’s not much help for the time of murder,” exploded Kobe. “What about the poison? How soon before he died did he take it?”

“Ah. That is even more difficult. Some poisons work quickly and some are quite slow. And we do not know how much he consumed. He may have lasted a few heartbeats, or taken a whole day and night to die, or even several days. I cannot be certain what he took until I dissect him and make certain tests. These, as you will hardly wish to spare any of your prisoners, will involve rats, whose tolerance for poison is different from that of humans. Still, we’ll know if it was quick, and may be able to guess at what it was. Though I have an idea about that.”

“Which is?” demanded Kobe.

“No, Superintendent! You must wait. I don’t enjoy making a fool of myself and avoid it at all costs.” His eyes slid to Akitada, and he smirked.

Akitada bit his lip. “Well,” he challenged Kobe, “either way, it eliminates highway robbery as a motive. Poisoning a man requires thought and selection. It is not random. Are you ready to admit that you made a mistake about Kojiro?”

“Certainly not. This does not clear him of the other charges.”

“Your people should not have moved the body. The killer may have left clues to his identity. Footprints, for example.”

“I know.” Kobe cursed. “It looked like a robbery. The money was gone, along with his horse. He was lying by the road. And my sergeant was so pleased with himself for identifying the missing Nagaoka that he decided to bring him back here for us to see. I’ll have his balls for this and fry them in oil. How’s Tora, by the way?”

Akitada suppressed a chuckle. “Seimei thinks he will do well.” Suddenly and perversely he felt a great deal better about the Nagaoka case. “Shall we go take a look at the scene while your capable coroner does his job?” he suggested, with a smile and bow toward Masayoshi, who looked at him in blank astonishment.

Kobe cursed again. “I suppose wed better. Before it gets dark.”

Dusk fell early, before they were well out of the city. It was bitterly cold. A sharp northerly wind pushed them onward and brought heavy dark clouds on their train. Kobe muttered something about the failing light, but Akitada would not turn back. The smell of snow was in the air, and he was afraid all tracks would disappear if they waited for the next day.

So they rushed on at a gallop, on horses requisitioned for government business, followed by the cowed sergeant and six mounted constables.

It was difficult to talk over the sound of the horses’ hooves and the gusts of wind, and for a while they simply covered ground. Soon the horses were steaming; flecks of foam from their muzzles flew back past the riders.

To the right and left of the raised highway, fallow rice fields and withered plantings of soybeans stretched into the murky distance. A few small farms huddled under dark groves of trees, like birds gone undercover from the freezing cold.

It began to snow when they were about halfway. The low dark clouds had steadily caught up with them, moving faster and lower, and when the first flakes materialized in the cold air, they stung their cold faces like pins and dusted their clothes and the horses’ manes.

The sergeant pulled up beside Akitada, perhaps to avoid catching more of Kobe’s wrath. He was eager to make up for his mistake and scanned the distance anxiously. “See that line of pine trees up ahead?” he shouted, pointing at a shadowy bank of darkness in the general murk. “That’s a canal. It crosses the road. About a mile after that is the turnoff.”

Minutes later they passed over the small bridge and turned down a narrower track.

“Where does this road lead, Sergeant?” Akitada asked.

“To a village called Fushimi.”

The name was familiar. “Isn’t that where Kojiro’s farm is?”

“Yes, sir. Though it’s a pretty large place, actually.”

Well, Nagaoka had said that his brother’s hard work had made his farm prosper. Akitada had a strong desire to see for himself. Since it was not far from where Nagaoka had been found, he thought Kobe might accept the need for a visit.

Eventually the narrow road cut through a forest of pines and leafless trees, and the sergeant called out to slow down. They came to a place where the ground was churned up by the hooves of horses and boots of men, and stopped. The sergeant pointed. “He was right over there! Against that rock!”

The sergeant, Kobe, and Akitada dismounted. Akitada cast a hopeless glance around. Those who had found the dead man, and those who had come later to get him, surely had destroyed any tracks left by his killers.

But when they reached the rock, the sergeant pointed out hoof marks in the soft ground. “They brought him on a horse,” he said. “We came on foot and carried him back to the highway.”

“ ‘They’?” Akitada crouched to stare at the indentations. His heart started beating rapidly. “A single horse! Perhaps his own? And whoever brought him took it away again. Could a single person manage? One man … or woman?”

The sergeant glanced back at the waiting constables on the road. “His companions may have stayed on the road.”

“Not likely under the circumstances, Sergeant,” snapped Kobe. “He was poisoned. I hardly think the murderer would bring along an escort while disposing of the body.”

The sergeant flushed. “The body was sort of flung down,” he said to Akitada, “not laid flat or sat up or anything. I suppose a strong woman, if she had a dead man draped over the saddle of a horse, could pull him off. A man, definitely. Getting him on is a bigger problem.”

They all crouched, studying the prints, but there were too many to make sense of. Akitada gave up first and followed the hoofprints away from the rock. The tracks slanted toward the road more or less along the same line on which they had arrived, and rejoined the tightly packed dirt track about fifty feet from the rock. The horse’s hooves had left clear marks in the moist earth of the grassy verge. To Akitada’s eye, the impressions looked the same both coming and going. “Come here, Sergeant,” he called. “Have a look at this. All the hoofprints are the same depth. Yet we know that, coming, the horse carried the body. That means the person who brought the body must have led the horse to the rock, and then ridden back to the road. Do you agree?”

The sergeant nodded eagerly. “You are right, sir. Let’s look for his footprints here.”

Akitada turned to Kobe, who had come up. “There was only one horse,” he said. “And only a single individual leading it. This individual lives within walking distance from here.”

Kobe glanced down the road where it disappeared among the trees in a haze of blowing snow. He scowled. “How far is the brother’s place?” he snapped at the sergeant.

The man flinched. “A couple of miles, sir. I can’t make out any footprints, except in this place here.”

In the growing darkness, they gathered and peered at a shallow impression. “Maybe a boot, not big, but not a woman’s, either,” guessed Kobe. Nobody could improve on this, and after another look around they gave up. The light was failing rapidly, and the snow fell more thickly.

“Let’s go to Kojiro’s farm,” said Akitada, swinging back in the saddle. “The weather is worsening and we will probably have to seek shelter anyway.”

Kobe scowled at the sky, but he nodded with a grunt, and the small cavalcade set out again.

They reached their destination just before it became necessary to light their lanterns. To Akitada’s amazement, Kojiro’s property was a manor house in a compound of buildings which was larger than his own in the capital. The entire compound was walled and had an imposing roofed gate.

“Are you sure we have the right place?” Akitada asked the sergeant. “This looks like some nobleman’s estate.”

The sergeant assured him that there was no mistake and applied the wooden clapper to the bell.

Kobe joined Akitada. “What do you make of this?” he asked, clearly thunderstruck. “The man acts like the merest peasant. If he has this much wealth, why didn’t he make an outcry? Where are all his wealthy friends? Or the poor officials who would gladly put in a good word for him for a small present?”

Akitada was completely out of his depth. “Perhaps he just does not have any connections and friends. Or maybe he does not believe in bribes.”

Kobe was snorting his derision when the gate opened on oiled hinges.

A boy of ten or eleven stood there, holding up a lantern and looking at them. Behind him an elderly man in a simple cotton robe came hobbling up, leaning on a stick. The wide courtyard was neat in the light of torches fixed to the walls of the manor house before them.

“You are welcome,” the old one said, a little out of breath. “I suppose you need lodging for the night?”

Akitada glanced up at the sky, which was nearly black and filled with swirling, dancing snowflakes. “Yes, thank you for your hospitality. The weather caught us unprepared. We are from the capital, investigating a murder which happened nearby. This is Police Superintendent Kobe with his men, and I am Sugawara Akitada.”

It was doubtful if the old man took in Akitada’s name, but when he heard Kobe introduced, his expression changed, and his eyes became fixed on the superintendent. “Are you the one that’s put my master in jail?” he asked, suddenly belligerent.

Akitada glanced nervously at Kobe to see how he would react to the sudden defiance of the old man.

Kobe scowled, being used to abject bows from mere peasants, then glanced around the compound again and cleared his throat. “In a manner of speaking,” he said. “I am in charge of the prisons in the capital. Who are you?”

Completely unimpressed, the man stood a little straighter. “I’m Kinzo. Senior retainer in charge of the manor while my master is away, jailed, though he is as pure and innocent as Saint Zoga.” He glared back at Kobe.

Kobe cast a glance at the sky. “I don’t blame you for your feelings,” he said peaceably, “but your master cannot be released until the evidence against him is either disproven or we find another suspect. That is why we are here now.”

The old servant’s fierce expression softened marginally. “You’d better come in,” he said grudgingly, and turned to lead the way.

They rode in, and the boy closed and latched the gate behind them. Kobe and Akitada dismounted at the house, where the boy took their horses. The others followed him to the stables.

Not unexpectedly, the house was dark and empty. Kinzo lit a lantern in the entry while they removed their boots. Then they followed him down dark corridors into a spacious room with a fire pit in its center. Heavy shutters to the outside were closed against the night and the weather. The room contained little beyond necessities: a few mats and cushions, several candlesticks with candles, and a large wooden chest of the type used by traveling merchants. It was reinforced with decorative metal corners, hinges, and locks on its drawers and had metal hafts at both ends to push carrying poles through. The only item in the room which was not utilitarian was a large and very fine scroll painting of a waterfall in a mountain landscape.

“Your master must be prosperous,” said Akitada, looking around.

“He has been blessed by Daikoku, god of farmers, but suffers the injustice and cruelty of the emperor Chu.”

“A well-read peasant,” whispered Kobe to Akitada, as Kinzo removed the wooden lid from the fire pit and lit the neat pile of charcoal at its bottom. Then he arranged cushions around it and invited them to sit.

“You may spend the night,” he said to Kobe. “Like the sainted Kobo Daishi, my master would not turn his worst enemy out on a night like this. Maybe you are trying to help him, but you’ve taken your time about it. Four times I’ve traveled to the capital and asked to see him, and four times your constables have turned me away. May Amida grant my master the unshakable spirit of Fudo. Last time, one of the constables said that not even my master’s wife was admitted any longer. I ask you, what wife may that be? My master does not have a wife.”

Akitada and Kobe looked at each other. Akitada said, “The constable made a mistake. The visitor happened to be my sister. She met your master once, and when she heard of his troubles, she took him some food.”

Now he had the old man’s full attention. “Ah! Forgive me, your honor. I didn’t catch the name.”

“Sugawara. I am a government official, and I, too, have taken an interest in your master’s case and am here to help.”

Kinzo suddenly smiled and bowed deeply. “An illustrious name! You walk in the footsteps of your noble ancestor who defied tyranny. You are indeed welcome. May the Buddha reward you for your help and may he reward your noble sister’s kindness. It is good to work on the side of the just. My master would never have killed his brother’s wife. He loves his brother more than his life. I told him so only a week ago.”

“Told whom?” snapped Kobe, coming to attention.

“Why, Master Nagaoka, of course. Your guards would not let me see my master, remember. Master Nagaoka stopped by to check on things and bring me news. I told him what the constable at the prison had said about a wife, and Master Nagaoka said it wasn’t true. I don’t suppose he knew about your sister, sir. He said the superintendent had warned him away, too, and that we must hope for a miracle to happen, for there was nothing that could be done anymore.” Kinzo shot an accusing glance at Kobe, who was staring at him fixedly.

“You say Nagaoka was here a week ago?” the superintendent asked. “When did he leave?”

“Why, the very next day. He had business elsewhere.”

“And how did he look when he left?” Kobe asked, giving Akitada a meaningful nod.

The old man had sharp eyes. He frowned suspiciously, but said, “As you’d expect. Like Kume after he saw the washerwoman’s legs.”

Kobe looked blank. “Who is Kume? What washerwoman?”

“It’s another story. Kume was a fairy,” Akitada explained. “The story has it that he lost his supernatural powers because he lusted after a mortal woman.”

The old man nodded. “A woman ruined Kume. A woman ruined Nagaoka. Her and that father of hers.”

“What is he talking about?” Kobe asked. “All I want to know is if Nagaoka was sick when he left here.”

“There was nothing wrong with his health,” snapped the old man. “If you’re afraid to spend the night here, you can ride home in the storm.”

Akitada said quickly, “No, no. You misunderstood. Nagaoka was found dead not two miles from here. He may have died the day he left here. The superintendent and I are trying to find out what happened to him. Do you know where he was going?”

Kinzo’s jaw dropped. “Master Nagaoka’s dead?” He shook his head in disbelief. “Oh, his karma was very bad! And now my poor master will be even more wretched than Fujiwara Moroie when his beloved died.”

“Come on, man,” snapped Kobe, “where was Nagaoka headed when he left here?”

Kinzo’s eyes widened. “Hah,” he cried. “That woman got him! I knew it. They say the spirit stays in its home for forty-nine days. Hers must have gone to Kohata. That’s where Master Nagaoka was going. Just over the hill to Kohata. And that evil demon was lying in wait for him.” He shook his head at the pity of it.