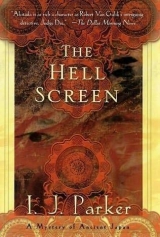

Текст книги "The Hell Screen"

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Akitada nodded. He was only mildly surprised that Nagaoka had recognized the origin of the objects. A man of his experience would certainly know what was contained in the Imperial Treasury. “Thank you. I thought so, but needed confirmation. What about taking the goods out of the capital and selling them in a distant province, or even in Korea?”

Nagaoka thought. “It is possible, but dangerous. You would have to assume in the first case that the thief has a buyer in mind who is already disloyal to His Majesty and is willing to pay a great deal to possess such goods. Such a man needs to be very secure in his position.”

Akitada looked at Nagaoka with new respect. The man was extraordinarily shrewd. Perhaps his profession had taught him a great deal about the secret desires of the powerful. “And in the second instance?” he asked.

“The thief would have to approach one of the foreign traders either here or at the port city of Naniwa. We have not had any trade ships arrive from Korea in over a year and none are expected to leave for there, since there has been a cooling of relations between our countries. This has been very bad for men of my profession, but it almost certainly means that such objects would not be offered to Korean merchants. They could not leave the country and, as I said, possessing them is dangerous.”

“Yes. I think you are quite right. Thank you. Do you yourself travel a great deal in your business?”

“Not often nowadays.”

Silence fell. Akitada wondered how to introduce the subject of the brother, when Nagaoka cleared his throat and said, “It was very kind of you, my lord, to take an interest in my family affairs the other day, but I hope you will not trouble yourself further on my unfortunate brother’s behalf.”

“Oh? You have had reassuring news, then? The police have another suspect, perhaps?”

Nagaoka did not meet his eyes. “Not precisely. Forgive me. I am not at liberty to discuss the case with anyone, but I have hopes the matter will be resolved soon.”

Now what had happened? Akitada hesitated, then asked the question which had troubled him all along. “I don’t suppose there is any question in your mind about the victim’s identity?”

Nagaoka stared at him dumfounded. “Of course not. I recognized my wife immediately.”

So that eliminated Akitada’s suspicion that the corpse was someone else!

Nagaoka looked miserable, but somehow Akitada did not think it was grief which had him so downcast today. Had Kobe threatened him? Or was there another, deeper reason? Had he decided it was too dangerous to have Akitada poke his nose into his family affairs? Either way the message was clear. Akitada was to stay out of the business.

Thanking Nagaoka again for his help with Toshikage’s list, Akitada took his leave.

The servant, less sullen and in an unexpectedly chatty mood, was waiting at the door with his shoes. “Winter’s here for sure,” he said for an opening. “A bit chilly out today.”

“So it is,” agreed Akitada, sitting down. “I see you have had your hands full with all the leaves. It must be a big job to take care of everything by yourself.”

“And little thanks I get from the master,” grumbled the man, busying himself with Akitada’s boots. “The funeral’s coming up. That’ll make more work, even if it is to be a small affair.”

“Very sad, yes. Did you like your mistress?”

A strange, secretive look passed over the servant’s face. “She was very beautiful.” He paused, then added, “And much younger than the master.”

“I suppose it must have been dull for a young lady here with your master gone so much from home?”

“Hmm,” said the servant, rising to his feet.

Akitada reached into his sash and counted some copper coins into his hand. “Here,” he said, “for your trouble.”

The servant grinned and bowed. They walked companionably toward the gate.

“She was making eyes at the master’s brother,” the man volunteered suddenly. “Fair drove him away, she did. But the master was blind to her ways. Always among his old pots and things, or going out to buy more. The gods only know why people want such stuff.”

“It is one of the mysteries of life. I suppose it was you who gave him the news about her death? That must have been difficult for you.”

The servant nodded. “That it was. You could have knocked me down with a thin reed when the police came pounding at the gate that morning, asking questions as if I was a thief. I had to tell them he wasn’t expected in till later and I had no idea where he’d gone. They kept at me like hungry gnats, but in the end they told me what’d happened and went about their business, leaving it to me to tell him. He got back soon after. I must say, he took it well enough. Turned right around and went to the jail to see his brother.”

“Were you surprised that the brother was arrested for the murder?”

“A bit. But then I thought, who knows what goes on in the heads of people? He used to get drunk a lot, and a man is not accountable for what he does then.”

It made for a simple and convenient explanation all right. But as Akitada walked homeward, he wondered where Nagaoka had spent the night of his wife’s murder.

SIX

Painted Flowers

More than a week passed without news of any kind. Akitada’s mother rallied a little over the next few days, but continued her steadfast refusal to see her son. Akitada was relieved. Since his visit to the shrine, he no longer actively hated his mother, but in his present detachment, he had no desire to face another scene. He occupied himself with drafting his report to the chancellor and reviewing his accounts. He visited the temple which supplied the monks whose chanting continued to fill the house, and presented several rolls of silk in payment for their services. He also negotiated the terms of the funeral rites, an action which met with disapproval from the betto, intendant of the temple, who murmured a gentle reprimand about having more faith in the prayers. He did, however, to Akitada’s sarcastic amusement, enter into the financial arrangements with the utmost thoroughness.

Akitada’s greatest concern was the lack of a letter from Tamako. He knew that they must be getting close to the capital by now, and it would have been easy to entrust a letter to one of the many government messengers who hourly galloped along the major highways leading to Heian Kyo. He fretted because he could do nothing about it.

Toshikage and Akiko had also not made an appearance for a number of days. Though no news was good news, Akitada could not help feeling uneasy about Toshikage’s problem. This, at least, he could do something about, and so he sent a brief note announcing his visit. On a dry, cold morning with hoarfrost on the roofs and terraces, he set out to pay a visit to his brother-in-law.

Toshikage’s house, though smaller than the Sugawara residence, was newer and altogether more impressive. It occupied four city lots in one of the best residential streets, and its gatehouse and main building were roofed with blue tiles and carved spouts like the imperial palaces, great temples, and houses of important nobles.

Akitada admired the complex from the street, reflecting that his own home, though in an old and prestigious quarter and certainly large enough by the standards which applied there, was sadly ramshackle and old-fashioned by comparison. His father and grandfather had been forced to sell off several parcels of the original grounds, so that the buildings now appeared cramped among the remaining huge trees and narrow gardens which surrounded them. To his own eyes and, no doubt, to his disapproving neighbors, they seemed sadly run-down. Worse, repairs had been done only as a last resort and the great roofs looked patched and ragged. The money had certainly never stretched to tile roofing, though it was far more durable than the thick, blackened thatch which covered the Sugawara halls, or the boards, held down by heavy rocks, which protected the outbuildings.

Akitada knew that his mother had been motivated by Toshikage’s wealth when she had chosen him for Akiko’s husband and he hoped wryly that all this would not be confiscated for theft.

He walked through the open gate into a wide courtyard. Servants were sweeping the gravel. One of them bowed deeply and ran ahead to announce him. Inside, a majordomo appeared, saw to his reception, and informed him with many bows that Lord Toshikage regretted that he was in conference. However, her ladyship would be delighted to receive her brother.

Akiko occupied a large, handsome room in the northern quarter assigned to the first lady of the house. Akitada found himself in a most luxurious and feminine setting. The entire wall facing him consisted of translucent oilpaper-covered sliding doors, closed now against the wintry weather, but promising a veranda and garden view outside. Shelves, filled with decorative objects, and cabinets took up the right wall, while a lovely painted screen and a series of lacquered clothes boxes occupied the left. The center of the polished black wood floor was covered with four thick grass mats which were surrounded by low curtain stands with richly tasseled brocade hangings.

Akitada’s sister reclined languidly on the mat among her silken bedding as a young servant girl brushed her shimmering black hair.

“What, still abed?” he teased, walking to her.

“Don’t be silly.” She smiled up at him. “1 am fully dressed. Though only just. Toshikage insists that I take it easy.” She patted her stomach, a tightly rounded shape covered by a saffron yellow silk gown under an embroidered Chinese jacket in chestnut brown.

“You look very fetching,” acknowledged Akitada, seating himself on a cushion. “That is a lovely jacket. And I had no idea that your hair had grown so long.”

Akiko was pleased. “Yes. It is nice, isn’t it? I have it brushed for an hour every morning.” She sat up abruptly and turned to the maidservant. “That is enough. You see I have a visitor. Go and fetch some wine.”

“Too early for wine,” protested Akitada. “I don’t suppose you serve tea?”

“Naturally. Toshikage gets me anything I like. Very well, Sachi. Make some tea instead, and bring some of the sweet rice cakes.”

When they were alone, Akiko rose. “How do you like my room?”

Akitada glanced around the large, elegant space. Filtered light came through the paper-covered doors. The room was comfortably warm, for large braziers filled with glowing charcoal stood about everywhere.

Akiko walked to the doors and opened one a little. “My private garden,” she said proudly.

Akitada joined her and looked. Beyond the open veranda with a red-lacquered railing lay a landscape in miniature. A tiny stream meandered among mosses. Spanned by a curved red-lacquered bridge, it flowed through a small pond and out under the tall plaster walls which enclosed the area. Hillocks rose and undulated around the waterway, cleverly planted with shrubs and dwarfed trees to resemble a wooded scene. A small wooden pagoda, precise in every detail, to the gilded bells at its eaves and the golden spire on its top, stood among some rocks, and a carved stone lantern beckoned from beyond the bridge as if the tiny path continued past a dense shrubbery into another scene.

“That one there is supposed to be Mount Fuji.” Akiko pointed to the largest hillock. “Does it look like it?”

Akitada had seen the sacred mountain. “An exact replica,” he lied. He glanced at Akiko fondly. “I am glad to see you so happy and that Toshikage is such a good husband to you.”

She laughed lightly. One of the nicest things about Akiko was her tinkling laughter. It lacked the infectious spontaneity of Yoshiko’s, but fell very pleasantly on the ear. For a moment, Akitada felt a strong sense of affection for both his sisters.

Akiko shivered and pushed the door shut. “It is so cold today,” she said. “How is Mother? No doubt she ordered more braziers for her room until you cannot breathe at all. I do not see how Yoshiko stands it day after day.”

Akitada’s warmth toward Akiko faded a little. His eyes fell on the large screen. It was painted with baskets and vases of flowers. The colors and shapes were lovely and natural, and the realistic detail with which the artist had rendered wisteria, bluebells, kerria, camellias, maiden grass, and many other plants astonished Akitada. Tamako would know them all by name, along with their medicinal properties. The painted flowers had been gathered in a number of charming painted baskets, porcelain bowls, and bamboo birdcages.

It occurred to Akitada that Tamako would find only bare rooms, stripped of their ancient and broken furnishings. Toshikage’s generosity made him painfully conscious of his own neglect. With her love for gardens, Tamako would enjoy such a screen above all the other luxuries he owed her.

“This is a lovely screen,” he told his sister, “Who is the artist? I would like Tamako to have one.”

“I have no idea,” Akiko said. “Toshikage ordered it for me. You must ask him. The colors are very bright, aren’t they? I expect it was expensive. Everything Toshikage buys is expensive. Just look at all the things in this room!”

Inwardly amused by his sister’s warning that the screen might be too costly for him, Akitada wandered about the room looking at hanging scrolls and carved vases, lacquered boxes, painted clothes trunks, silk-covered curtain stands with heavy silk tassels, and writing sets, games, makeup stands, and mirrors in gay profusion.

One item gave him sudden pause. It was a small ceramic figurine of a floating fairy, dainty, detailed, and painted in faded but exquisite colors, down to the gilding of her headdress and drooping jewelry. “Did he give you this also?” he asked, his heart beginning to pound in sudden panic.

Akiko glanced at it without much interest. “I don’t remember that!” she said, vaguely astonished. “He must have sneaked it in to surprise me.” She looked at the figurine more closely. “Pretty, but a bit old, isn’t it? It looks foreign. Like some of the Chinese statues of Kwannon in the temple.”

“Yes.” She had a surprisingly good, if untutored, eye. The figurine was certainly old and dressed in Chinese costume like the representations of the Goddess of Mercy. However, unless he was mistaken, the little lady was one of the missing imperial treasures. Surely there could not be two of these around. He looked at Akiko and wondered if her husband was a thief after all.

“What is the matter?” she asked.

Seeing her standing there, a worried look in her eyes, her hand pressed against the swelling abdomen, he decided he could not burden her with his suspicions. He walked back to his cushion and sat down. Warming his hands over one of the braziers, he said lightly, “I was thinking that I have not treated Tamako very well. It is high time that I showed some appreciation for my wife.”

Akiko trilled one of her laughs and came to sit with him. “And so you should!” she said, shaking her finger at him. “Men are always wrapped up in business, taking us for granted when night comes. Thank heaven Toshikage is still attentive. It is no wonder so many highborn ladies take lovers on the side.”

The maid came in with the tea. She filled their cups from the bronze pot, placing it on one of the braziers afterward to keep warm. Before she left, she bowed and told Akitada, “The master’s guest has gone. The master says he will see you when you have finished your visit with her ladyship.”

Akitada thanked her, but Akiko pouted.

“You just got here,” she complained. “I thought you wished advice on what to buy for Tamako. I know all the best shops for silks and gewgaws.”

Akitada sipped his tea and smiled. “I shall come back often now that I know the way. And the other day I went to a silk merchant near the market to shop for some fabric for a court robe for myself and some silks for Yoshiko. They seemed to have an immense selection.” He mentioned the name of the establishment.

Akiko nodded. “Yes. That one is good. But why in heaven’s name are you buying stuff for Yoshiko? She never wears anything but old cotton rags.”

Akitada rose. “That is precisely why I did it. Unfortunately, the lovely colors were a little too lively. She reminded me that Mother might put us all into mourning shortly.”

“Oh!” Akiko struggled up. “What a horrid thought! It is bad enough that we will be in seclusion for weeks, with taboo tablets hanging at the gate and around our necks! I do wish that they would shorten the mourning period for a parent. It seems so pointless.”

And so it was, thought Akitada on his way to Toshikage’s study, though Akiko’s pronouncement lacked proper sentiment. But he of all people could hardly fault her, for he felt neither love nor grief for his dying mother.

Toshikage was looking unexpectedly glum and was not alone. A young man in the dark robe of a government clerk rose when Akitada entered. Akitada recognized him in an instant as one of Toshikage’s sons. He had his father’s round face, though he had not yet run to fat.

“Welcome, dear brother,” cried Toshikage, coming to embrace him. “Please forgive the delay. I had a rather unpleasant visit from my superior. This is my son Takenori. He is my confidential secretary and knows all about the, er, problem.”

Akitada bowed to the young man, who returned the bow politely, his face expressionless.

“Come, let us sit down. Some wine for your illustrious new relation, Takenori!”

Akitada took his seat on one of the silk cushions in the center of the room. Like Akiko’s quarters, Toshikage’s study was the epitome of comfort and luxury. Here, too, large braziers spread their pleasant warmth. Here, too, mats covered the floor and papered doors filtered light from outside. Toshikage’s doors had carved grilles and, instead of painted screens, scrolls covered his walls, and the doors of the built-in cabinets were painted with landscapes. Shelves above the cabinets held his books and document boxes, and his writing utensils and paper were laid out on a low window seat under a round, screened window. A bell with a wooden hammer hung there also, suspended from a silk rope, in case he wished to summon a servant.

The son poured, and Akitada accepted the cup, saying pleasantly, “You must be a great help to your father, Takenori. I had no idea that you were already old enough to hold a position of such responsibility. Did you attend university?”

“Yes, sir. Thank you, sir.”

Akitada wondered if the young man was shy. He certainly did not engage in conversation.

To ease the awkward moment, Toshikage filled in. “Takenori is twenty-eight years old. My other son, Tadamine, is twenty-seven. He serves at the northern front and was recently promoted to captain.” Fatherly pride and something else—a sadness?—sounded in Toshikage’s voice.

“You are to be congratulated on your children. Are there daughters also?”

Toshikage brightened a little and chuckled. “No such luck, or I could make some shrewd connections with the ruling Fujiwaras. Are you by any chance asking because you wish to take another wife?”

Akitada was taken aback by the suggestion. He would never take another woman into his household while Tamako occupied it. Renewed worries about his family’s welfare surfaced and were banished. “Not at all,” he said firmly. “I am well content with my present arrangements.”

“And so am I,” cried Toshikage. “Your sister is all an old man like myself could wish for. She has such elegance and beauty it takes my breath away.”

Akitada smiled warmly at his brother-in-law. When he glanced at Takenori, however, he noticed the young man’s clenched hands. So there might be some ill feeling here! Not a pleasant situation for Akiko, who had probably been a bit naive to congratulate herself on being the mother of the next heir. She had planned without considering Toshikage’s grown sons.

Toshikage, unaware of the effect of his speech on his son, continued happily, “And now she is to be a mother soon. She tells me it is to be a boy. Women know about such things, don’t you think? What about your wife? You have a son, I hear. Did she carry him high in her belly? For that is what Akiko does. A lively child! He kicks already to open the door to life!” Toshikage laughed and his own belly trembled with merriment. His son got up abruptly and busied himself with some papers at the desk.

“Well,” said Akitada blandly, “if it is not a son, you will have a daughter to play marriage politics with. And, in any case, you have sons already.”

Toshikage’s face fell. “My sons are well enough,” he said, “but Takenori here is promised to the church. He has postponed taking the tonsure to see me through the present problems at work but will enter the Temple of Atonement in Shinano province in the coming year. And Tadamine insisted on joining the army last year. There has been a great deal of fighting up north.” He sighed deeply.

Akitada looked at Takenori with surprise. The young man returned his glance stolidly. Akitada told him, “You are to be admired for such a serious spiritual choice at your age. Few young men are so devout, though it is said the Buddha himself followed the calling before he had reached the prime of life. But will you not miss your family and the life of the capital?”

Takenori said, “I see my path clear. There is nothing for me in this world.”

Toshikage shifted uncomfortably. Akitada wondered whether Takenori had rejected the temptations of a worldly career or felt abandoned by his father. He glanced uncertainly at Toshikage and thought he saw tears in his brother-in-law’s eyes. So it had been the young man’s own choice, just as apparently it had been the other son’s wish to become a soldier. To have both sons turn their backs on a career in the capital where they could support their father and eventually carry on the family name was a tragic blow. But eventually, of course, it would benefit Akiko, particularly if she did bear Toshikage more sons, and if Tadamine lost his life on the battlefield. No doubt his sister had taken these things into account. Thus were grief and happiness forever intertwined in the rope of fate.

“Takenori,” said Toshikage with a sigh, “stop your fidgeting and sit down. We must tell Akitada about our visitor.”

It developed that the director of the Bureau of Palace Storehouses himself had called on his assistant to express his dissatisfaction with certain rumors he had heard.

Toshikage was distressed. “Apparently the story of my having the lute got out past our department,” he said. “The director does not show his face very often in the office. His is one of those appointments which merely produces a good income. He was angry because someone made insinuations about lax administration at a party he was attending.”

Akitada watched his brother-in-law as he reported on the director’s visit. Toshikage appeared more frustrated than conscious of guilt. His son looked angry. When he met Akitada’s eyes, he cried, “It was an intolerable insult to my father and may cost him his position.”

Akitada said soothingly, “Well, nobody takes gossip very seriously. Next week they will have something else to talk about. I meant to tell you that my questioning the local antiquarians has at least given us the encouraging news that the thief, if there was one, has not offered any of the objects for sale.” He gave Toshikage a hard look. “I don’t suppose they could simply have been misplaced. Perhaps, like the lute, they were removed temporarily only and will be returned?”

“Impossible,” cried Takenori. “Father and I checked carefully. They have been missing for months.”

Toshikage nodded with a sigh. “Yes, I am afraid Takenori is right. We have made a most careful search since I last spoke to you. We did so after hours so as not to attract the notice of my colleagues.”

Fleetingly Akitada wondered if Takenori was taking refuge in Buddhist vows because he foresaw his father’s downfall and exile. They would certainly protect him from prosecution. But what about the figurine in Akiko’s apartment? “Are you quite certain, Brother, that you have not forgotten bringing home some of the things? They could easily have become mixed up with your own treasures.”

Toshikage stiffened. “Of course not. I am not yet in my dotage even if I am quite a bit older than you.”

“Sorry. I did not mean to imply anything.” Seeing the anger in Toshikage’s face, Akitada broke off awkwardly. How was he to pursue the matter? Any suggestion of his suspicion might offend Toshikage so seriously as to lead to a break between the families, or worse.

Toshikage had fallen into a hurt silence, but Takenori looked flushed with anger. When he saw Akitada’s eyes on himself, he protested, “My father is most meticulous in his duties. It is so unfair! I think that we should propose that this house be searched. It will establish his innocence once and for all.”

Toshikage cried, “Heavens, no! I forbid it. What are you thinking of? It would upset Akiko, and in her delicate condition that could endanger the child.”

Akitada, more than ever at sea about Toshikage’s culpability, sought desperately for something else to say and remembered the screen.

“Forgive me, Brother, for speaking so carelessly. I really was thinking of the many wonderful things I saw in Akiko’s quarters.”

Toshikage looked slightly mollified. “It gives me pleasure to surround beauty with more beauty,” he said sentimentally.

“She is a lucky woman. And you are a remarkable collector with a fine eye for art. I particularly admired the screen with the flowers.”

“Oh, that! Yes. Does it look well there? It cost a pretty penny. The fellow is getting a name at court.”

There was something not quite right about Toshikage’s response. Had the man not seen it for himself ? Akitada said, “It looks very well indeed. Was it you who chose to place it just to the side of the sliding doors to the courtyard? In the summertime it must look as if the garden had moved into the house.”

Toshikage beamed. “Hah! Very good. No, Akiko must have put it there. Clever girl!”

So Toshikage did not venture to his wife’s room regularly. Apparently, like the emperor’s consorts, Akiko proceeded to her husband’s quarters for their intimacies. More importantly, it was possible that Toshikage had nothing to do with the suspect figurine. It made the problem more complex, for someone else in the household could have placed it there. If, indeed, it was part of the imperial treasure and not some similar piece.

Akitada turned to Takenori. “By the way, your father has given me a description of the missing items. It occurs to me that you, too, may be familiar with them. Could you give me your recollection of what they looked like, please? It will help confirm your father’s memory.”

Takenori turned out to be less than helpful. He stumbled through some vague descriptions, getting the colors of the figurine wrong and being corrected by his father, and finally gave up with the comment that he did not take much interest in such things. The outcome was largely inconclusive, except to confirm that Akiko’s figurine was at least a close replica of the emperor’s and that Toshikage was not aware of its presence in his house.

Well, he could do no more at the moment without alerting father and son to his suspicions. With an inward sigh, Akitada gave up, and then remembered the screen. He said to Toshikage, “I am really impressed with the flower screen. Akiko could not tell me the name of the artist and referred me to you. I thought I might commission something similar for Tamako. She is very fond of gardening.”

Toshikage clapped his hands. “That is an excellent idea. Takenori took care of the commission for me. Please look up the address and tell Akitada how to get there, Takenori!”

His son obediently rose and went to the shelves, where he opened one of the document boxes and searched through the contents. He returned with a sheet of paper, which he handed to Akitada. “This contains the information, sir,” he said politely.

It was a copy of a bill of sale for “one screen, four panels, decorated with flowers of the season in exotic containers” to be delivered by the end of the Leaf-Turning Month to His Excellency, the assistant director of the Bureau of Palace Storehouses, in return for ten bars of silver. The bill was signed, “Noami, of the Bamboo Hermitage, by the Temple of Boundless Mercy.”

Ten bars of silver! It was an enormous price to pay a mere artisan. Artists usually scraped together a living hawking their wares at markets and during temple fairs. Akitada said, “At these prices the man must live in a palace. Where is this Bamboo Hermitage?”

Toshikage laughed. “I told you the fellow is becoming the fashion. Did you notice the detail? He is said to study a flower from the time the bud opens through all the stages of bloom until the petals fall. Such patience costs money. But I have an idea. I have wondered how to express my gratitude to you, dear Brother, and to welcome you home properly at the same time. Allow me the pleasure of making you a gift of such a screen. Takenori shall go with you, and you shall tell the man what you want. When it is done, I shall have the screen delivered to your lovely wife.”

Akitada was embarrassed. Under no circumstances did he wish to obligate himself to Toshikage, at least not until he knew exactly where his brother-in-law stood in the case of the missing treasures. “Thank you, Brother! You are most generous, but this particular gift to Tamako must be my own. You understand, I am sure?”

Toshikage raised an eyebrow and grinned knowingly. “Say no more, dear Brother! I understand completely. The lady must be reassured of your affection. I know the feeling.” He chuckled.

Akitada turned to the son. “There is no need for you to come, but perhaps you can give me directions to the artist’s house?”

It appeared that the painter lived in the western part of the city. Takenori hinted that it was in a rough neighborhood.

“What’s this?” cried Toshikage. “You said nothing to me about the place being dangerous.”

Takenori lowered his eyes humbly. “Forgive me, Father. I did not know until I was accosted by a pair of aggressive beggars. I got away from them easily enough, but Lord Sugawara may not be so lucky.”