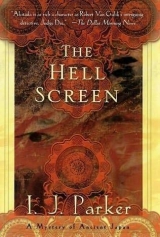

Текст книги "The Hell Screen"

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

“You are Sugawara?” he said, staring at Akitada. “But you are not expected till the end of the month.”

“I know. I received news of my mother’s illness and rushed ahead by myself. I just arrived and thought it best to report to Their Excellencies as soon as possible.”

“Hmm. Nobody’s here now. I suppose you can leave a note.” The young man rummaged among papers, found a sheet and writing utensils, and pushed them toward Akitada, who dashed off a few lines. When he raised his head, he saw that the young dignitary was still eyeing his clothes suspiciously. Taking the note, the young man read it with a frown, then asked, “Are you pressed for funds, by any chance?”

Interpreting the question correctly, Akitada said stiffly, “Not at all. If you are referring to my attire, I rode ahead of my entourage and did not bring any luggage. I had to make do with some old clothes put away years ago.”

The young noble’s face reddened, then relaxed into a smile of amusement. “Oh. I see. For a moment, I thought you might be someone masquerading as a ranking official. Well, you’d better go back home until you can equip yourself properly. Their Excellencies are very particular about dress. I’ll see to it that they get your message. We’ll send for you when you are needed.”

“Thank you.” Akitada did not return the young man’s smile. The incident would, he was sure, make an amusing tale to pass around among the fellow’s noble friends. Seething with anger, he gave the young man, who undoubtedly outranked him, a mere casual nod and turned on his heel.

He walked home quickly and without looking into people’s faces. The sun shone, but there was a chill in the air. The blue of the sky and the drifts of fallen leaves under his feet had lost their brilliance and seemed merely a sickly pale and dull brown. Far from making a triumphant return after a dangerous and highly successful assignment, he felt he was taking up where he had left off. After all these years he still shrank in embarrassment from what people thought of him. It was as if his mother’s reception had brought back a host of old miseries. In truth, he reminded himself, there was no reason for him to be ashamed. He was no longer poor and he had made a name for himself in the far north. He had handled difficult situations well and he would be of use to the emperor in the future. It was ridiculous that he still cringed before his dying mother and some noble youngster in an expensive robe.

When he got home, Akitada found that his sister Akiko had arrived. She greeted him with a big smile and immediately posed to show off an extremely handsome robe of embroidered silk.

“How do I look?” she cried.

“Wonderful,” he said, and meant it. Akiko had filled out and looked rosy and contented. Her long hair almost reached the floor and shone with care and good health. He looked from her to. Yoshiko. The contrast was painful. Yoshiko was the younger by two years, but her thinness and the plain robe, along with the unattractively tied-up hair, made her look like a middle-aged servant. His heart contracted with pity.

Akiko was still posing, sideways now, stroking her robe down over her belly and arching her back. “Do you really think so?” she asked, her eyes twinkling.

Yoshiko gasped. “Akiko! Are you sure?” she cried.

It took Akitada another moment. “You are expecting a child,” he cried, and went to hug her. “How splendid to hear such happy news on the very day of my return.”

Akiko sat down complacently. “I have known for a while now. Toshikage is beside himself with pride.” She gave Akitada a look. “You knew that he has two grown sons?”

Akitada nodded. He had seen the documents when Akiko’s marriage settlements were being arranged, a process which had frustrated everyone because of the long delays involved in carrying papers between Heian Kyo and the distant province of Echigo.

“Of course, my position was impossible until now. Unless I can produce a son, I have nothing to look forward to but widowhood living on your charity in this house.” She made the fate sound like abject penury. “Toshikage is no longer young. He could die any day. And then everything will go to his sons, and nothing to me.”

Akitada’s jaw dropped at Akiko’s cool analysis of her situation. It told him that her happy looks had nothing to do with marital bliss, a fact she confirmed almost immediately.

“It was not easy,” she said, patting her belly with a sigh. “My husband is willing, but not always able. I am told men lose their desire with age. You cannot imagine what I’ve had to do to keep him coming to my bed.”

Akitada said sharply, “I have no wish to hear such intimate details. And if you felt that way about Toshikage, why did you consent to the marriage? You knew that I would take care of you.

Akiko laughed bitterly. “Oh, yes. But who wants to grow old serving Mother as a target for her ill temper, while going around looking like a common maid? Look at Yoshiko! Anything is better than that! I am Lady Toshikage now, with my own household. I have many beautiful gowns, my rooms are furnished luxuriously, and I have three maids. And now that I bear a child—a son, I think, and with luck the future heir—my position will be permanent.”

Akitada looked at Yoshiko, saw the averted face, the clenched fingers in her lap, and felt anger at Akiko. “Your sister has too much work, with your mother so ill. Your place should have been here to help her,” he said sharply.

Akiko’s eyes grew wide. “With my own house to run? And in my condition?” she cried. “Toshikage would never permit it.”

As if on cue, Akitada’s brother-in-law arrived. He was a corpulent man in his fifties, and he approached smiling widely, until he saw Akitada’s clothes. Then he stopped uncertainly.

Akiko followed his glance. “Heavens, Akitada,” she said, “where did you find those old rags? You look absolutely ridiculous. Toshikage no doubt thinks you’re some itinerant soothsayer.’“

“Not at all!” cried her husband. “I recognized the noble features of my brother-in-law. Pleasure, my dear fellow! Great to be related!” He approached and embraced Akitada, who had risen.

Akitada returned the pleasantries and invited him to sit down. When he congratulated Toshikage on his imminent fatherhood, his brother-in-law smiled even more widely and cast an adoring look at Akiko, who simpered in return.

“Lovely girl, your sister,” he told Akitada, “and now she’s made me doubly happy at my advanced age. I tell you, I feel quite young again.” He laughed until his belly shook and clapped both hands on his pudgy thighs. “We are to have little children running around the house again! It will be wonderful.”

Akitada began to like the man. As a proud father himself, he soon involved Toshikage in cheerful discussions of children’s games and antics. Seeing the ice thus broken, the sisters withdrew, and Akitada sent for wine and pickles. In due course, he turned the conversation to news and gossip about the government. At first Akitada had only a vague sense that the subject depressed his brother-in-law. But Toshikage became increasingly ill at ease, fidgeting nervously, sighing, and making several false starts to convey some information.

“Is there anything the matter, Brother?” Akitada finally asked.

Toshikage gave him a frightened glance. “Er, y-yes,” he stuttered, “as a matter of fact, well, there is something … that is, I could use some advice….” He paused and fidgeted some more.

Akitada was becoming seriously alarmed. “Please speak what is on your mind, Elder Brother,” he said, using the respectful form of address for an older blood relation, to encourage Toshikage.

Toshikage looked grateful. “Yes. Thank you, Akitada. I will. After all, this is a family affair, since it also affects Akiko and our unborn child. Er, well, there has been trouble in my department. Some false stories are being told about me.” He gulped and gave Akitada a pleading look. “They are quite untrue, I assure you. But I am afraid—” He broke off and raised his hands, palms up, in a gesture of helplessness.

Akitada’s heart fell. “What stories?” he asked bluntly.

His brother-in-law looked down at his clenched hands. “That I have… privately enriched myself with, er, objects belonging to the Imperial Treasury.”

THREE

The Cares of This World

After a moment of shocked silence, Akitada asked, “Do you mean that someone suspects you of having stolen imperial treasures?”

Toshikage flushed and nodded. “It all started with a stupid misunderstanding. In an old inventory list I found that a lute called Nameless had been mislabeled ‘Nonexistent.’ Then some fool had drawn a line through the entry and made the notation that the instrument had been removed from the storehouse, but did not say by whom. When I started asking questions, nobody seemed to know what had happened to the lute, and there was no record that someone from the palace had sent for it. This started me checking all the lutes in the treasure-house. I could not find Nameless, but saw that another lute needed repair and restringing. Because it was the last day of the week, I took it home with me to have our usual craftsman work on it at my house. Foolishly I did not sign it out. It so happened that evening I was having a party for friends. Someone must have seen it lying there, for when I returned to work the next week, the palace sent for me and asked what an imperial lute was doing in my house. It was embarrassing, I tell you, especially since the person did not quite believe my explanation.” Toshikage broke off and sighed deeply.

“Hmm,” said Akitada. “I grant you that was a bit unpleasant, but I don’t see that a single incident should cause you serious trouble. Surely you returned the lute?”

“Of course.” Toshikage rubbed his brow with shaking fingers. “And I got strange looks from everybody when I did. You know how people are. They were whispering behind my back, snickering, exchanging glances. The worst was that they have been doing it every time I make some innocent remark, perhaps mentioning that I was thinking of buying a present for Akiko, or commenting on some misplaced object.” He sighed again.

“Nasty.” Akitada nodded. “Your colleagues must be rather unpleasant people.”

Toshikage looked surprised. “I never thought about it, really. I suppose they are. What shall I do?”

“Who is behind it, do you think?”

“Behind it? What do you mean?”

“Well, if there is a plot to blacken your name, then there must be someone, or perhaps several people, who instigated it.”

Toshikage’s expression went blank. He asked in total astonishment, “Do you really think so?”

Akitada almost lost his patience. It was becoming clear to him that his new brother-in-law was naive and not given to pondering arcane matters. Instead of explaining, he said, “Of course. Who saw the lute in your house?”

“Oh, everybody, I suppose.”

Akitada bit his lip. “Who was at your house?” To forestall another “everybody,” he added quickly, “Their names, I mean.”

“Oh.” Toshikage wrinkled his brow. “Kose was there, of course, and Katsuragi and Mononobe. Then some people from the Bureau of Books and someone from the Bureau of Music, I don’t recall their names, and some of my personal friends. Do you want their names also?”

“Perhaps later. Were the first three the only ones from your office?”

Toshikage nodded.

“Do you have any particular enemies among any of the men who attended your gathering and may have seen the lute?”

“Enemies?” Toshikage was shocked. “Of course not. They may not all be close friends, but they certainly were not enemies. I am not in the habit of inviting enemies to my house.”

Akitada sighed inwardly. “Could anyone other than the three from your office—what were the names—Katsuragi, Kose, and… ?”

“Mononobe.”

“Yes, Mononobe. Could anyone else have recognized the lute as belonging to the Imperial Treasury?”

Toshikage shook his head. “I doubt even Mononobe would. He just started working in the bureau.”

“Very well,” said Akitada. “We are making progress. More than likely either Kose or Katsuragi, or both, recognized the lute. They may have pointed it out to Mononobe, and one or all of them later passed the story around your office. From that point on, someone, perhaps one of the three, perhaps someone else in the bureau, decided to make use of the incident to blacken your reputation. You will have to find out who that man is and put a stop to it.”

“How can I do that?” cried Toshikage. “I cannot very well accuse them.”

“Do you want me to pay your colleagues a visit and ask questions?”

Toshikage looked horrified. “Good heavens, no! I would really be in trouble.”

Akitada looked grim. “Then I do not know how I can serve you in this matter.”

“I thought you might find the missing items. Then we could return them quietly and the whole matter would die down.”

Akitada stared at his brother-in-law. “What items? You said you returned the repaired lute. Do you mean that other instrument? What was it called? Nameless?”

“No. Everybody knows Nameless has been missing for a long time. The other things started disappearing later, after the gossip about my having taken the lute.”

Akitada sat up straight. “What else is missing?” he asked, fearing the worst.

Toshikage closed his eyes and recited tonelessly, “A lacquer box with a design of wheels, given to the eighth emperor by a Korean ambassador; two amulet covers, gilded silver, once the property of Empress Jimmu; a painted jar, said to have contained the true toenail of the Buddha; a small carved statue of a fairy; a gilded censer; and the golden seal given by the Chinese emperor to one of our embassies to Changan.”

Akitada breathed, “Good heavens!” Such a loss was a scandal of the first magnitude. “How many people know?”

Toshikage began to look frightened. “Only I know of all of them. I think Katsuragi has been checking the inventory, and he and Kose know about the jar and the box. Maybe the statue also.”

“Have they reported the losses to you?”

“No.”

“Didn’t that puzzle you?”

“I supposed it was because they thought I had been taking the things.”

Oh, Toshikage! “Have you mentioned the theft to anyone?”

“No, I was afraid to. I think we should try to find everything and put it back.”

“Easier said than done. Shouldn’t you have reported to your superior? Who is he, by the way?”

“The director is Otomo Yasutada. And no, I did not.”

“I think you had better. It does not look good for you to keep this matter to yourself… unless there is something you are not telling me?”

Toshikage waved his hands. “No, no. I have no secrets from you, Akitada. Where do you think the items are?”

“That depends. If they were taken for resale, they could be in a shop or in someone’s home.” Toshikage looked shocked. “But if they were taken purely to get you in trouble, they may be hidden someplace.”

“Oh. Well, you must find them.” Toshikage bit his lip. “But why get me in trouble? I have not done anything to them.”

“Since you cannot remember having made any enemies, there must be another reason. Who would get your position if you were dismissed?”

Akitada watched his brother-in-law digest this new thought. He was beginning to look distinctly uneasy and said, “Kose would be promoted in my place. But I cannot believe it of him. The thief must have sold the objects. Even that is terrible to consider. How can I clear myself ?”

“It may be difficult. Well, I shall ask around in the shops. Cautiously, for it would not do for anyone to find out that we are looking for imperial treasures.” Akitada found a sheet of paper and some writing utensils. “Here, make a list of the items for me.”

Toshikage seized on this task eagerly. “Thank you, my dear Akitada,” he muttered when he was done, passing him the list. “I shall, of course, pay you back if you have to buy the items.” He paused, frowning. “I don’t suppose it would be too expensive? They are all old things.”

Oh, Toshikage, thought Akitada again. Aloud he said, “It all depends on the seller and the dealer. I have been away for a long time. Who might buy such things for resale?”

“If it’s dealers in antiquities you mean, I only know Nichira. His store is near the eastern market. But since I am hardly in a position to squander my money on such baubles, I am not the best person to ask. As for private collectors, well, it could be anybody. All the Fujiwaras have the wealth, and several of them have famous pieces. Kanesuke, for example, and Michitaka, and the chancellor, of course. And then there is Prince Akimoto. But surely you cannot mean to visit any of them?”

Akitada shook his head. “Not the great men, certainly. I might look in on some of the dealers and antiquarians, though. That will do for a start. Meanwhile, I want you to make an initial report that you cannot locate certain items and wish to take an inventory.”

Toshikage looked unhappy but promised.

Before Akitada could change the subject to something more pleasant, Akiko came back. “Mother wants to see you, Akitada.”

His spirits sinking further, Akitada rose and went to his mother’s room. Yoshiko was sitting next to the pile of bedding which covered the frail body. Lady Sugawara fixed her son with a glare from eyes sunken into the hollows of her thin face. Her pale skin flushed unnaturally. She snapped, “Surely you did not report to the controllers looking like that?”

Akitada glanced down at his disreputable gown in dismay. He should have remembered to change before coming to see her. He said apologetically, “I am afraid so. You see, I have not brought any suitable clothes, and you insisted I go immediately.”

Lady Sugawara sucked in her breath sharply and turned her head away. “Oh! You are impossible!” she moaned. “You did this to spite me! No doubt you wish me dead and hope to speed me on my way by shaming me publicly. Go away! I cannot bear to look at you.”

Outside in the corridor, Akitada stopped and took a deep breath to control the sudden sickness which rose in his belly like a live thing. She was an old woman and in pain, he reminded himself. He must not mind so much. Perhaps she did not mean it.

But the logic was in vain. He was both angry and sorry now that he had rushed home, hoping to make his peace with at least one parent before death parted them forever.

Instead of returning to Toshikage and his sister, Akitada went to his own room, where he sat until night fell, staring out at the dark garden until Yoshiko came.

“Toshikage and Akiko have left,” she announced, adding, “You have no light.” She went on silent feet to light a lamp, and brought it over to him. Sitting down near him, she waited. When

Akitada made no move to talk, she asked, “Will you eat something if I join you?”

He looked at her thin, drawn face and felt guilty. “Yes. Of course.” He tried a smile. “Please do join me. I hate to eat alone.”

They shared a simple meal, and when they were done, Yoshiko said hesitantly, “You may have to return to the palace soon. It occurs to me that we have a very nice piece of dark blue silk. Will you let me sew you another gown? I am very handy with my needle.”

He was touched. “Thank you. It is a good idea, but one of the servants can do it.”

“I am much better at it. I made Akiko’s gown.”

He recalled the elegant appearance of his other sister. “Did you? It was quite beautiful. I had no idea you have such talents.” A thought occurred to him. “If I buy some silks tomorrow, will you sew two robes, one for you and one for me?”

She looked down at the plain cotton gown she wore. “I do not need anything. Fine silk is wasted on mere housework and nursing.”

“It would give me pleasure to see you in it when we share our meals.”

She smiled with sudden affection. “In that case, yes. Thank you, Elder Brother.”

Akitada went shopping the next morning. Leaving the house to the accompaniment of the monks’ chants, he felt as if he were escaping from a prison. The weather was warm and sunny, and even the bare willows of Suzaku Avenue made a fine show against the limpid blue sky. The recent rain seemed to have washed the world clean, and the ordinary people in the streets looked remarkably tidy. The great thoroughfare bustled with foot traffic, ox carriages of noble gentlemen and ladies, and riders on urgent business.

He passed the red-lacquered gate of the Temple of the City God and turned right into the business quarters of the capital. Here well-dressed shoppers mingled with bare-chested porters carrying heavy bales and boxes on their backs. An occasional red-coated constable, bow and quiver slung across his shoulder, kept an eye out for pickpockets.

The increased traffic and noise told him that he was approaching the markets, and he turned into a street of large shops, looking for silk dealers and antiquarians.

He found Nichira’s almost immediately. Whitewashed plaster walls and high screened windows covered with dark wooden fretwork faced the street. A sign announced proudly, “Nichira’s Treasure House of Antiquities,” but the shop door was plain. Akitada walked through and found himself in a stone-paved entryway just below a raised platform of polished wood. The wooden floor stretched all the way to the dim back of the building. As far as he could see, the walls were lined with floor-to-ceiling shelves, and rows of raised tables stood everywhere, forming passages crisscrossing the central space.

From nowhere, a thin young man appeared at Akitada’s side and knelt to help him with his shoes. Stepping out of his own clogs, he led Akitada up onto the wooden floor, bowed, and asked what his honor would like to see.

“Hmm,” said Akitada, glancing around him. Every surface of shelf space and every tabletop were covered with objects. There seemed to be hundreds of small boxes of every description, and thousands of small ceramic and porcelain vessels. The shelves held figurines and masks, rolled scrolls and yellowed books, lamps and candlesticks, carved writing utensils and jade seals, games and musical instruments, religious as well as secular items. “May I look around?”

The assistant bowed, and followed Akitada around the room. Closer inspection proved that none of the objects on display were of sufficient antiquity to qualify as imperial treasures. Akitada gave up. Turning to the assistant, he asked, “Do you perhaps have a very old lute?”

The assistant bowed again and led him back to one of the shelves. It held some twenty different instruments, all of them nice, but none old enough to be “Nameless.” Frowning, Akitada pursed his lips and said, “No, no. Nothing so ordinary will do. Don’t you have something really special? Really old?”

The young man hesitated, then said, “Perhaps Mr. Nichira had better be called.”

Mr. Nichira duly appeared. He was short, fat, and quite self-possessed. Casting an appraising eye over Akitada’s brocade hunting robe, he bowed. “I am told the gentleman is looking for a very special old lute? Might I have some particulars about the instrument?”

Akitada bit his lip. They were getting on dangerous ground. How to ask for an object without describing it in recognizable detail? He pretended ignorance. “Yes. Well…” he said, glancing helplessly around the large room. “Not necessarily a lute, but something really special…. I suppose it need not be a lute as long as it is rare… it is a gift for someone highly placed, you see… very highly placed.”

To his relief, Mr. Nichira smiled. “I quite understand. It is not always easy to find just the right thing for a connoisseur, is it?”

Akitada raised his shoulders helplessly. “No. I thought… But perhaps you might know better what…” He let his voice trail off.

“Quite. Might I ask your honored name?”

“Sugawara.”

The name rang no bell for Nichira. Akitada was more relieved than hurt. The dealer said, “Ah, yes. If your honor is not particular about its being a lute, I may have some other very special objects to show you.”

Akitada murmured something about putting himself entirely into Mr. Nichira’s hands, and was led into a private room behind the showroom. Here the dealer begged him to be seated on a fine silk cushion, poured a very strong, fruity wine from a translucent porcelain flagon into a jade green cup of Chinese origin, and then produced several silk-covered packages, which he began to unwrap. None of the lovely things were the missing treasures, but Akitada managed to chatter about antique seals, lacquer boxes of great antiquity, and statues of fairies—not because he expected Nichira to produce them, but in hopes that the dealer might have heard about such things from his colleagues or suppliers. No such luck. But the thought of suppliers prompted another question.

Picking a lovely old flute from among the items on the table, Akitada said, “How did you come by this? It is quite unusual.”

“It is part of the estate of Lord Mibu Kanemori. The widow was in straitened circumstances and sent for me. She says it’s been in the family for more than two hundred years.”

Akitada turned the flute this way and that, studying the workmanship closely. “The arrangement of the finger holes is unique. Does it have a good sound?”

Nichira looked impressed. “Does your honor play?”

“A little,” Akitada said modestly. He tried to place his fingers over the holes, itching to try out the sound produced by such an instrument. He once had a wonderful old flute himself, a present from a young noble friend, and he flattered himself on his skill playing it.

“Please allow me to hear you perform,” begged Nichira. “I have no skill myself.”

Polite fellow, thought Akitada, pleased, and put the mouthpiece to his lips. The sound which emerged when he blew was quite lovely, high and clear rather than mellow like his own flute. He attempted a more complicated piece of music, struggling a little with the unfamiliar finger holes.

Nichira listened with rapt enjoyment. Akitada was impressed with the dealer’s appreciation of music and said so when he finished. Nichira burst into highly flattering comments. After that they were entirely in charity with each other. Akitada bought the flute, trying not to wince at the price, and had no trouble getting Nichira to part with some useful information.

The other antiquarians likely to have very old and precious goods were called Heida, Kudara, and Nagaoka. Nichira helpfully supplied their addresses. Nagaoka was semiretired, handling a few transactions out of his family residence. All respectable dealers investigated the provenance of any articles brought to them.

“It is necessary to tell the buyer,” explained Nichira. “You asked about the flute. Knowing the previous owners adds to the value of the item.”

Akitada parted contentedly from Nichira, promising to return on another occasion.

He found a silk shop in the next street. This store was open to the street, its shutters raised to allow passersby a view of the large interior, where apprentices bustled about carrying rolls of silk to seated customers. Akitada entered, and a senior saleswoman introduced him to the treasures of the shop. Akitada, who was used to the meager offerings in the northern province, felt his head spin at the colors and patterns of silk and brocade which were offered for his inspection. His own needs were fairly easily met, but he lingered over the silks for Yoshiko.

The assistant was a graceful middle-aged woman of great patience. Akitada pleasurably pictured Yoshiko in a new wardrobe. A lovely deep rose silk which changed to paler pinks depending on how the light struck it seemed to him particularly elegant and youthful, but it was after all winter, and he eventually settled on a deep copper red. Then, on an impulse, he added the rose silk after all. Matching thinner silks for undergowns, five each, their colors complementary yet distinct, had to be selected next. The assistant brought the lengths of silk tirelessly, combining and recombining their shades in layers until he was happy with the results. The copper red fabric would cover layers of pale gold, lilac, sand, and moss green, while the rose silk would be lined in leaf green, deep red, light red, and white. Immensely pleased with his choices, Akitada paid another astronomical sum and had everything sent to his residence.

Poorer but happy, he stepped out into the street to the sound of bells. It was already time for the midday rice, and he decided to postpone visits to the other antiquarians, except for Nagaoka, whose house was on his way home.

The thought of home, reminding him of his mother, ruined his good mood. In addition it began to look more and more as though someone in Toshikage’s office was hiding the treasures for his own purposes. The thought raised unpleasant possibilities. Was it merely an attempt to get Toshikage dismissed and so win a promotion? Or was the thief bent on vengeance and planning to have the treasures discovered on Toshikage’s person or in his house? The offense of stealing from the emperor was serious enough to warrant public humiliation, confiscation of property, and banishment to a distant province. Toshikage’s family would suffer the same fate as he. While Akitada, by virtue of bearing a different surname, would not be involved, his sister Akiko and their unborn child certainly would share her husband’s fate.

Nagaoka lived in a quiet residential quarter, not quite for the “good people,” nor for mere tradesmen, either. His house was a typical wealthy merchant’s home on a double plot, hidden from the street by tall wood screening. A simple sign above the decorative doorway read, “Nagaoka, Antiquarian.”

Akitada raised his fist to pound on the fretwork gate, when it was suddenly flung open and he found himself face-to-face with an old acquaintance.

The expression on the other man’s face changed rapidly from surprised pleasure to acute suspicion.

“Kobe!” cried Akitada heartily. “What a coincidence! I intended to pay my respects eventually, but family matters have kept me occupied.”

“What are you doing here?” growled the other man, as usual bypassing politeness to get to the heart of the matter.

Akitada raised his brows. “Now, that is hardly a friendly greeting after all these years,” he said lightly. He realized belatedly that there was something quite different about the police captain: Kobe did not wear his customary uniform of red coat and white trousers. Instead he was attired rather formally in dark silk. “I was calling on the antiquarian for some information. But are you no longer with the police?”