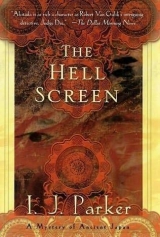

Текст книги "The Hell Screen"

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

It was nearly dark outside. Akitada glanced across the dim courtyard at the looming shapes of the residence and felt another pang of regret that in his absence little had been done to take care of it. “There are also the repairs to the house and gardens.”

Tora’s eyes opened wide. “But winter is coming, sir. It’ll be best to wait until spring.”

They walked to the well to wash their hands. The water in the bucket was icy, and the night air bit their wet skin painfully.

“Well,” said Akitada, grimacing as he hurriedly dried his hands on the fabric of his trousers, “if you do have some spare time, you might ask around about those actors. They seem to have roamed all over the monastery that night. One of them may have seen something. And try to find out if any of their women were outside around the hour of the rat. They call themselves the Dragon Dancers and work for an old man by the name of Uemon.”

“The easiest thing in the world,” cried Tora, rubbing his hands. “A man like myself knows all the wine shops along the river where the actors usually spend their money—” He broke off as Seimei joined them.

“Beware of letting the tiger loose in the market,” Seimei said to Akitada, with a meaningful nod toward the grinning Tora. Tora meant “tiger” and he had lived up nobly to the name since he adopted it. But he fancied himself as an assistant investigator of crimes, and he had had some success, though his methods involved copious drinking bouts and bedding material witnesses, much to the disapproval of Seimei.

“Thank you, Seimei. The advice is well taken.” Akitada chuckled. “But you did not come for that, I am sure.”

“Oh, no. Lord Toshikage and his lady have arrived. They are in her ladyship’s room.”

Akitada hesitated. He had no wish to see his mother. But Seimei corrected himself. “I meant your lady’s room, sir.” After another moment’s confusion, Akitada realized that Seimei referred to his own room, or rather his former room.

Shaking his head at the changes wrought in a few hours, he headed that way. Yori’s giggles and women’s laughter came from behind the door, and he braced himself for a scene of chaos, with the women excitedly digging through Tamako’s wardrobe, which would be flowing from innumerable trunks and covering every available surface, while his son romped about freely amid the general upheaval. He opened the door, hoping to extricate his brother-in-law from the chatter of women and children, but found to his surprise a tidy room with a happy family seated decorously on cushions around his desk.

All the trunks were closed and placed neatly against the walls, and a small painted screen and several handsome curtain stands stood around the gathering to protect them from the cold air coming from the doors. The faces turned toward him shone with laughter and good cheer in the light of candles. Tamako sat near the teapot; Yoshiko was holding Yori on her lap; Akiko, all smiles, had placed a hand protectively on her stomach; and Toshikage, next to his wife, rose to greet him. It suddenly struck Akitada that an extraordinary change had come over this house which, until most recently, had been filled with nothing but the mournful chants of the monks and nervous whispers of servants in the corridors.

The most profound change had nothing to do with his mother’s illness. He could not recall ever hearing laughter in this house, or the shouts of children, or indeed seeing a happy gathering of family all under one roof. Feeling a surge of gladness, he greeted Toshikage with a hearty embrace.

The women were drinking tea, but Toshikage had a flask of warm wine, and Akitada accepted a cup of that, warming his frozen fingers on the bowl before letting the warm liquid spread a glow through his stomach. The two braziers, together with the screens, kept the chill at bay, and he relaxed into blissful leisure. Tamako informed him that she had entertained everyone with stories of the far north, and that now it was his turn. He obliged, and as they listened, asked questions, and chattered, they passed a giggling Yori from hand to hand. It was a more pleasurable time than Akitada could have imagined.

It was Akiko who broke the happy mood. “By the way, Mother looks dreadful,” she suddenly informed him in a tone which was almost accusatory, though whether she held him accountable for his mother’s decline or blamed him for her unpleasant experience was not immediately clear to him. “She cannot last the night. You had better think of the arrangements, Brother.”

He sighed. “Don’t worry. The arrangements have been made. How are you feeling, Akiko?”

This distracted her. She gave Toshikage a coy smile and patted her stomach. “We are very well, my son and I,” she said proudly. “And Toshikage is quite charmed with your Yori, so he will take enormous care of us. Won’t you, Honorable Husband and Father of our Son?”

Toshikage smiled broadly and bowed to her. “The most tender care, my Beloved Wife and Mother of our Child.” He turned to Akitada and said, “You are blessed with a delightful family, my Brother, and I count myself the luckiest man alive to be a part of it.”

Akitada was touched and made a suitable and affectionate reply, but thought privately of that unhappy young man who was Toshikage’s oldest son. These thoughts led inescapably to the problem of the thefts from the Imperial Treasury, and he would have taken Toshikage aside to discuss the matter if the door had not opened to admit Tamako’s maid with the evening rice.

Genba had outdone himself. There were platters of pickles, bowls of fragrant fish soup, mountains of soba noodles, and piles of stuffed dumplings. These delicacies were accompanied by rice and steamed vegetables from the cook’s own kitchen. Dinner was another pleasant interlude, but finally Yori became tired and fretful. The women rose together to put him to bed.

On her way out Akiko had to pass Akitada and paused briefly. “By the way, Brother, it is the strangest thing, but that little figurine of the floating fairy you were so interested in? It has floated away again, and Toshikage swears he knows nothing about it. Have him tell you about it.”

Akitada’s eyes flew to Toshikage and he saw the other man flush to the roots of his hair. He waited till the door had closed behind the women before he asked, “So you recognized the figurine?

Toshikage raised his hands. “I never saw it. I remembered what you said about instructing Akiko about the history of the little treasures and went to visit her room the very next day. She told me about the figurine, but when we looked for it, it was gone.” He gulped down a cup of wine and sighed.

“And?”

Toshikage said miserably, “Akiko described it. Your sister has an excellent memory. It sounds like the floating fairy from the treasury. I don’t think there could be two of them. I swear to you, Akitada, I did not put it there!”

“I believe you, but someone in your household must have done so.”

“Impossible. Who would do such a thing? For what purpose?”

“I wonder why it was left in Akiko’s room, and where it is now.”

“Why leave it at all?”

“Perhaps as a warning to you?”

Toshikage looked absolutely confused. “A warning? About what? I don’t understand.”

Akitada sighed and thought.

After a moment Toshikage said, “It’s a miracle the director did not see it. Remember the unpleasant visit I had from my superior?”

Akitada nodded.

“I had meant to show him the screen in Akiko’s room and would have done so if you had not called to see your sister. Can you imagine what would have happened if the director had seen the thing?”

“Yes. But I thought you said the director was there to reprimand you. Why would you show him around under the circumstances?”

“Oh, it was not like that. I had mentioned the screen to him a few days earlier at the office and invited him over. In fact, at first I thought that was why he had come.” Toshikage subsided into a misery of sighs and head shakings. “What can it all mean?” he muttered.

Akitada was beginning to have an idea. But it was hardly one he could share with Toshikage. If he was right, the truth would be a far bigger blow to his brother-in-law than a mere dismissal from office, no matter how embarrassing the circumstances.

TEN

The Dark Path

Lady Sugawara died the next morning.

It was Tamako who brought the news to Akitada. He was in his father’s room, remote from the women’s quarters, and thus unaware of the event. Rising early, he had slipped from under the covers gently so as not to disturb his sleeping wife and had walked softly to the kitchen to fetch a brazier and some hot water for tea, and then to his new study.

The room still depressed him. He lit as many candles and oil lamps as he could find against the darkness of closed shutters, but still a clammy, unpleasant aura remained. For a while he walked around rearranging his things where once his father’s had stood. In the process he found the old flute he had bought from the curio dealer and decided to cheer himself up with some music.

He was badly out of practice but found some old scores and soon became immersed in the intricacies of fingering and timing the notes.

He was not aware of his wife until she walked up quickly and took the flute from his lips.

“What is the matter?” he asked blankly. “It was not all that bad, was it?”

Tamako looked down at him sadly. “No, Akitada. But you must not play anymore just now. It is your mother.”

He rose abruptly. “Heavens! Am I not even permitted such a small pleasure in my own house? That is intolerable, and I shall not allow her to dictate my life any longer.”

Tamako looked at him with tragic eyes and sighed. “Yes, I know. Your mother is dead.”

He gaped at her. Dead? His first reaction was relief that it was finally over, the long dying, the dreadful pall which had lain over this house so long. The relief immediately made way for shame, and then depression. Perversely, the event, so long expected, now seemed sudden, badly timed, too soon. “When?” he asked, and felt his heart contracting.

Tamako put a hand on his arm. He had not realized that his fists were clenched at his sides. His right hand hurt and when he raised it, he saw that it still held the antique flute, broken now; a splinter of bamboo had cut one of his fingers. Tamako gave a soft cry and took the pieces, laying them on his desk. Pulling the splinter from his hand, she said, “A short while ago. Another hemorrhage. Your sister was feeding her the morning gruel. I found Yoshiko covered with blood and incoherent with shock and took her away. The doctor has already seen your mother, and the maid and I have tended to her.” She hesitated. “Do you want to go to her now?”

So Tamako had spared him the sight of his mother’s blood-covered corpse. With a shudder he recalled the terrible scene when his mother had cursed him, the gaunt, distorted face, the sunken eyes blazing with hate, heard again the hoarse voice spitting out her vilifications until the words had drowned in a flood of gore.

Tamako gently stroked his arm. “Don’t look so. You knew it was going to happen. It was time.”

Akitada turned away from her sympathy. How could she understand that he felt mostly hatred for his own mother? Anger, regret, hopelessness, pain, but above all hatred. “Yes. I knew,” he said harshly. “I even wished it. And, oh, yes, it was time! She poisoned everything she touched. My life, Yoshiko’s, Akiko’s also! She would have poisoned yours, too, and our son’s! I am glad it is over!” He laughed. “Finally it is over!” Looking around at his father’s room, he shouted, “They are both gone! Gone! The house is ours! Our lives are our own! We can finally find peace and happiness….” He collapsed on his cushion and covered his face with his hands.

“Shh! Akitada!” Tamako came to kneel beside him and touched his arm. “Don’t! The servants will hear you! Please, you must not!” She saw that his face was wet with tears and, with a small moan of pity, took him into her arms.

“My own mother hated me so much,” he sobbed into her hair, allowing her to hold him, rocking back and forth with the pain, “that she died without taking back her curses. What have I done to deserve that? Tell me, what have I done?”

“Shh!” Tamako crooned, patting him as if he were little Yori, “Shh, she could not help it. Death came too quickly.”

Eventually he calmed himself and straightened up. “I suppose,” he said, drying his face with his sleeve, “I had better go pay my respects.”

Akitada had seen death often. It had never been a casual encounter, even when the dead person had been a stranger. But he had never hesitated or flinched as he did now at the door to his mother’s room. He had stood here many times in his life, never eagerly, always wishing himself elsewhere. But always he had faced up to the encounter, because it was expected of him. With a sigh, he opened the door.

His mother’s room was brighter than it had been in her lifetime. Many candles shone on the thin figure of the old woman as she lay, surrounded by the figures of the chanting monks. She was wrapped in the voluminous folds of a heavy white silk gown. Someone (Tamako?) had cut her hair like a nun’s, suggesting a deathbed devotion which Lady Sugawara had never felt in life. It made her look younger, and her features seemed peaceful.

Akitada forced himself to study the face which, when alive, had regarded him with irritation, dislike, cold fury, and indifference, but never with love. He thought it ironic that those who had led blameless lives and whom he had loved had often died with contorted features. There was great perversity in death.

For the benefit of the chanting monks he knelt and bowed, staying in this reverent pose for an adequate time before rising and withdrawing. It was done!

The next days were taken up with funeral preparations. He concentrated on his duties, putting aside his bitterness for a calmer time. Both the house and its inhabitants wore willow-wood tablets with the “taboo” character inscribed on them, to warn outsiders of the ritual contamination of death. The taboo did not, of course, discourage the Buddhist monks, who seemed to take over the house and the lives of its inhabitants and would until after the funeral. But theirs was a different faith from the old religion, which abhorred the very thought of death.

No business of any type could be transacted during this period, and no visitors appeared, though Akitada received many messages of condolence from friends and from his mother’s and father’s acquaintances. It was all very proper and expected, except for one incident.

The day after his mother’s death, Yoshiko came to see him. She was still very pale and looked frail in her rough white hemp gown. Kneeling in front of his desk, she looked with a sigh down at her folded hands. “There is something I have to tell you,” she said. “I have thought about it a long time, for it may be painful for you.” She looked up at him then, her eyes large and serious. “You know, I would not hurt you for the whole world, Akitada.”

Akitada’s heart fell. He had been worried for a while now that she was in some sort of trouble, and Tamako had suspected the same. Hiding his fear behind a smile, he said warmly, “I know. And there is nothing you could tell me that would make any difference in the way I feel about you, Little Sister. Please speak!”

She did not return his smile, saying bluntly, “I am afraid I caused Mother’s death.”

Her tone was so flat that Akitada stared at her. This lack of emotion was quite unlike Yoshiko, who had always had a soft heart. For a moment he wondered whether her presence during the final paroxysms had perhaps deranged her mind. To reassure her, he said briskly, “Nonsense! She was dying. What could you have done that would have made any difference in that certainty?”

Yoshiko shook her head stubbornly.

He searched his memory for Tamako’s report, regretting for the first time that he had not seen his mother’s body immediately. A hemorrhage, Tamako had said. Probably just like the one he had witnessed himself. But Yoshiko had not been with him then. He tried again, “Mother died of a hemorrhage. How could that be your doing?”

“Oh, Akitada. Can’t you guess what happened? I quarreled with her. I knew how she felt about you, knew that one more provocation could bring on a final attack, but I could not keep still any longer.”

Half-afraid of the answer, he asked, “What did you say?”

“I asked her why she would not see you, why she treated you so badly when you had rushed all that way to be at her side. She got very angry and said it was none of my business, but I would not leave it alone. I argued with her and accused her of lacking a mother’s feeling for her son. That was when she started screaming at me.”

Akitada winced. So it had been his mother’s hatred for him that had finally killed her after all. Looking at Yoshiko’s white, strained face, he said, “Don’t blame yourself! It was kind of you to speak for me, but pointless. I have known for a long time that she did not love me. It is clear that I was foolish to think she would change on her deathbed. As for motherly feelings, I suppose she simply never cared for me. I have tried to account for it by the fact that she was as disappointed in me as was my father. I am so sorry that I should have been the cause for your distress.”

Yoshiko cried, “Oh, no! That wasn’t it at all. Oh, Akitada, I didn’t come here because I needed you to console me. It is true, I blame myself for provoking her, but I know Mother was dying, and perhaps it was good that she spoke to me before she did.” She paused and looked at Akitada anxiously. “You see, I don’t think she was your mother at all.”

After a moment’s stunned silence, Akitada said, “You must have misheard something. My father never had any secondary wives.”

“He did! We just did not know. I think your mother died when you were born, and you were raised by our mother. And I think she never forgave you for being another woman’s son.”

Akitada blinked. He felt as if he had walked into a dense fog. He wondered again if Yoshiko had gone mad under the recent strain. But she looked calm enough except for the nervous twisting of her hands. “What makes you think so?” he asked.

She leaned forward a little, her face tense, her voice high with emotion as the words tumbled out. “Mother said so in so many words. Actually, she screamed it at me! It was horrible, but if you think about it, it explains so much! I have thought about it ever since. Imagine all that resentment, years and years of it, holding it in for fear of Father. And when Father was gone, she still would not speak because you were the heir and could have ordered her out of the house if you had known. Oh, she probably knew you would not abandon her totally, but she was afraid that you would find her another place to live, and she could not have borne that. Only now she was dying, and you had brought your wife and heir home, and she knew there was no point in keeping quiet any longer. All the hatred and jealousy of nearly forty years, of knowing that Father preferred your mother to her, that your mother gave him a son, when she had no children at all, until Akiko and I were born, all of it poured out. She ranted on until she choked on her own misery, and then the blood came up and she died. It was dreadful!” The stream of words halted abruptly on a little gasp, and Yoshiko looked at him tearfully.

Akitada’s mind reeled. “What exactly did she say?” he demanded. “What were her words?”

Closing her eyes, Yoshiko thought back. “She said, ‘He’s no son of mine!’ and then, ‘She was a person of no importance! What did he see in her?’ and then she said, ‘He insulted me and my family by bringing her child into my house, to raise him as his heir for all to see and pity me!’ “ She opened her eyes. “There were many hateful words about this other woman.”

Akitada was silent, caught in the monstrous shock of the thing. He stood up and walked to the veranda door, opened it, and stepped outside. Standing on the edge of the veranda, he stared down at the fishpond, where a few dead leaves mimicked the golden and scarlet fish beneath the dark waters. Just so his father must have stood many times. What thoughts had been on his mind? The bond between himself and his father suddenly seemed strong and unbroken. It was as if he had always known deep inside of himself the truth he had just been told. The truth within! Somewhere he had read those words, but could not now recall where.

His sister sat wringing her hands in her lap. After a long time of watching him anxiously, she whispered timidly, “I am so sorry, Akitada. I did not mean to hurt you.”

Akitada had been thinking of his father loving another woman, who was his mother, and was startled. “You have not hurt me,” he said in a tone of wonder. “On the contrary, it is a great relief to me. Only, now my father’s dislike for me seems even more strange.”

His sister said quickly, “I thought about that, too. I think he must have pretended to dislike you because of Mother.”

Akitada turned to look at her uncertainly. That idea would take some getting used to. How do you divest yourself of almost forty years of resentment toward your father in one moment? There were too many bad memories to be explained away, one by one. It was not going to be easy. He sighed and said, “At least it should not be difficult to find out the truth.”

“You are not angry with me, then?”

“Of course not. And stop worrying about having caused… your mother’s death. The slightest aggravation would have done the same.” As he watched Yoshiko rise, her slender figure obscured by the stiff folds of the hemp gown, he forced a smile. “I suppose I shall have to wait until the forty-nine days are up before I see you in one of your pretty new gowns.”

“Forty-nine days? We mourn a parent for a full year.”

“No, Yoshiko. As head of this family, I decree that after the funeral we shall wear dark colors until after the ceremony of the forty-ninth day. Then all mourning will be put aside. So get busy with your needle.”

She opened her mouth to protest, then smiled. “Yes, Elder Brother. As you say.”

After she left, Akitada examined his feelings. On the whole he felt enormous relief that he was the child of another woman, as yet a mythical figure. It was one thing to be hated by one’s own mother, but quite another if a stepmother had done so. A woman’s jealousy of a rival could well cause her to reject that woman’s child.

He felt a mild curiosity about that long-dead young woman, so hated by her rival, and so beloved by his father. For if he had not loved her, surely the woman whom Akitada had thought of as his mother would not have hated her son so bitterly and long. He recalled, too, moments when his stepmother’s guard had slipped and she had revealed her bitterness toward her late husband, her many complaints about his political and financial failure, her bitter reminders that she had married someone unworthy of her own family. And gradually the stern, unforgiving image of his father softened in his memory until it became almost human.

He was still pondering these relationships when the door opened softly and Seimei entered with another message of condolence.

Seimei! Akitada looked at the old man with new eyes. He put the message aside unread and said brusquely, “Please take a seat!”

Seimei was surprised but obeyed.

“I have just had some extraordinary news, and it occurs to me that you must have known about it for many years.”

The old man looked blank. “What is that, sir?”

“It seems the woman who claimed to be my mother all these years unburdened herself on her deathbed and told my sister that I am another woman’s son.”

Seimei paled slightly, but his eyes did not flinch. “It is true, sir,” he said. “Lady Sugawara was not your mother. I regret that you had to find out before I could speak.”

Akitada stared at him. How could the old man be so calm? A bitter resentment rose in his stomach. “Why did you not tell me?

“I was bound by a promise to your honored father, but I was about to do so now, since Lady Sugawara has passed out of this sad world.”

Akitada felt stark disbelief. This Seimei was a stranger to him, not the friend he had trusted from childhood, to whom he had confided every hurt and all his uncertainty about his parents, and whom he had loved like the father he had wished for. This man had kept a secret from him through all those years, a secret which would have saved him so much heartache! How could he have done it?

Seimei was still looking fully at him, but there were tears in his eyes now. “I gave my word, sir,” he repeated.

His word! Was keeping one’s word more important than a child’s misery? Was it more important than seeing the adult struggle with self-recrimination? As recently as yesterday Akitada had still agonized over the relationship between himself and his supposed mother.

Seimei said softly, “I promised your father, because we feared for your life.”

“What are you talking about?”

Seimei flinched at the harshness of Akitada’s voice. “Lady Sugawara believed she would have a son of her own. There came a time when she was certain she was with child and she made arrangements for an accident to happen to you. Your father discovered it in time and sent you away.”

All these years Akitada had believed that his father had driven him out of the house because he disliked him so intensely that he could not bear his sight any longer. He was moved profoundly by the thought that his father had cared for him after all. He stared at Seimei, but the tears welling up in his eyes blurred the old man’s image until he could barely see him, and he turned away to regain his. composure. The news raised more questions. After a moment he asked, “If he discovered his wife in such a plot, why did he not divorce her?”

“He, too, believed her with child. By the time it became apparent that she was not, you were quite happy in the Hirata family and refused to come home.”

Yes, that was true. His professor at the university had taken him in. Hirata and his daughter Tamako, now Akitada’s wife, had both welcomed the deeply distressed Akitada with such unaccustomed kindness and warmth that he had rejected out of hand his father’s rapprochement.

“But why did you not speak after my father’s death?” Akitada asked. “And why did my father not leave a letter for me?”

“Your father asked for my silence again on his deathbed. I do not know if he feared for your safety or wished to protect Lady Sugawara and your sisters. I could only give my word that I would do as he asked.” Seimei quoted softly, “ ‘First and foremost be faithful to your lord and keep your promise to him.’ “

Akitada closed his eyes. Confound Confucius! He had much to answer for in this case, he thought bitterly.

“You would not wish me to break my word to you, sir, would you?”

Akitada looked at the old man and saw tears sliding down the wrinkled cheeks into his straggly beard. He sighed. “No, I suppose not. Tell me about my mother!”

“Her name was Sadako. She was the only child of Tamba Tosuke, one of your father’s clerks. Her family was provincial, very poor but respectable. When his wife died, Tamba Tosuke suddenly took Buddhist vows without a thought to his daughter’s welfare. People took it for a sign of his extreme devotion, but your father was angry and he paid for the young lady’s support. In time he fell in love with her and married her, though arrangements had been made for another marriage to the late Lady Sugawara. Your mother died when you were born, sir, and then your father brought you to this house to be raised by Lady Sugawara, hoping she would be a mother to you.” Seimei paused, then added diffidently, “Her ladyship came from very different circumstances than your poor mother.”

Akitada knew it well enough. Of course she despised the child of a woman of the lower classes, one who had been her predecessor and her rival. She had never allowed anyone to forget her own pedigree.

A sudden thought struck him. What if she had passed some of her qualities on to Akiko? Had not Akiko also wished to be rid of the sons of her husband’s earlier marriage? He was immediately appalled at his lack of faith in his sister. Akiko was merely spoiled, not evil. She could be selfish and thoughtless, but she was not cruel. Still, she might already have caused trouble in Toshikage’s house. He had to make an effort to undo it! That, too, was one of the legacies his stepmother had burdened him with. He considered bitterly that he was about to become the late Lady Sugawara’s chief mourner in an elaborate funeral ceremony. It was ironic. In a way he was bound as irrevocably as Seimei to carrying out the wishes of the dead.

The funeral took place after dark. They set out for the cremation site in procession. Torchbearers and monks chanting Buddhist mantras walked ahead. Lady Sugawara’s corpse, washed again and wrapped in white cotton sheets perfumed with incense, lay in an ox-drawn carriage behind drawn curtains made of her embroidered court robes. Ahead walked Seimei, carrying the sacred lamp, and Saburo followed behind with a censer from which clouds of incense perfumed the night air. The mourners walked behind, Akitada first, followed by Yori in the arms of Tora, and Toshikage. The three women followed in hired litters. After them walked the Sugawara servants and friends. The long line moved slowly, silent except for the chanting of the monks, through the deserted streets of the capital.

The cremation ground was outside the city. A site had been prepared for them, with white sand strewn about the funeral pyre, and temporary shelters had been erected for the mourners.

Akitada took his seat among the men and prepared for the long night’s watch. There was a clear sky with many stars, and it was bitterly cold. He had made arrangements for open braziers to be placed in all the shelters, but they made only a slight difference. He glanced worriedly at his son, who sat next to him. Yori was bundled into so many quilted robes that his round, rosy face looked absurdly small among all the silken coverings. Akitada had insisted that hemp was to be worn over ordinary clothing and only by his sisters and the servants. He, Tamako, and Yori wore dark silk robes instead. He had chosen that single subtle gesture because he was no blood relation to the dead woman. Since both dark silks and hemp were customary in mourning, outsiders would hardly realize the significance. If anything, they would ascribe the silk to his position as head of the family.