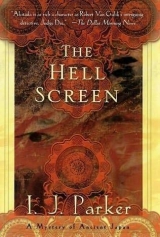

Текст книги "The Hell Screen"

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Kobe’s face relaxed momentarily and a smile twitched his lips. “Promoted,” he said. “To superintendent.”

“You don’t say!” Akitada chuckled and bowed. “My sincerest congratulations. You deserved it.”

“Thanks. You did not do so badly yourself. Provisional governor. And you crushed a rebellion or two, I hear. The New Year should bring a generous promotion.”

“Not with my luck.” Akitada paused and glanced at a servant who had cracked open the gate and was listening with an expression of avid curiosity. Kobe followed his glance and took Akitada’s arm to pull him a few steps away. Behind them the gate clanked shut.

Akitada looked back and then in growing puzzlement at Kobe. “What brings you here? Is something wrong?”

“Murder,” remarked Kobe placidly. “My men seem to be making a mess of the investigation, so I came to see what’s what.”

“The antiquarian has been killed?” If the trail of the imperial treasures ended here, Toshikage’s predicament had just taken a new, more ominous turn.

But it appeared that Nagaoka was alive.

“His wife,” said Kobe. “Apparently killed by his brother. A love triangle. Pretty young wife agrees to meet elderly husband’s younger brother in a romantic setting. Somehow they argue, and he kills her. Husband is understandably distraught. Mixed loyalties! Should he help the police and have his own brother sentenced for murder, or should he protect the man who killed his beloved wife? He has not been cooperative so far.”

“I see.” It was a tricky problem for a Confucian scholar. Was a man’s first duty to his wife or to his blood brother? More to the point, Nagaoka would hardly be in a frame of mind to answer questions about antiques.

“What did you want from him?” Kobe’s eyes studied Akitada’s face with bright interest.

Akitada could hardly divulge Toshikage’s problem to the police superintendent, yet Kobe must be told something. Akitada hesitated just a fraction too long, and Kobe’s eyes suddenly became intent. “Aha! I was right. What do you know about the case?” he snapped, his good humor gone in a flash. “Come on! Your arrival is just a little too coincidental.”

“I swear I know nothing about it,” said Akitada, trying to think of some innocuous reason. Then he remembered his flute purchase. “I, er, have taken up flute playing, and am interested in antique instruments. Nagaoka’s name came up as someone who might help me.”

Kobe was unconvinced. “You are here to look at flutes?”

Akitada nodded. “I have had four long years in the northern wilderness to practice. You have no idea how soothing the sound of a flute is when you are snowed in and the cares of the world hang heavy on you.”

Kobe looked at him askance. “Sounds depressing to me. I don’t suppose you’d better bother Nagaoka at present. He has about as much of the cares of the world as any man can bear.”

“I can see that. When did the murder happen?”

Kobe hesitated for a moment, then said, “Night before last. In a temple west of the capital. The brother was found with the wife’s corpse in a locked room. It’s a clear case and he confessed right away, but then Nagaoka talked to him in jail, trying to get him to withdraw the confession. I could see our case falling apart in court and came to warn Nagaoka off.” Somewhere another bell rang the half hour. Kobe said, “I must get back. Are you walking my way?”

Akitada hesitated. He cast a glance back up the street at the closed gate of the Nagaoka residence, then said, “I am on my way home. My mother is very ill, and I had better not be too late. Can we meet tomorrow?”

“Of course. Stop by my new office in the palace. Sorry about your mother.”

They exchanged bows and walked off in opposite directions. Akitada went around the next corner and stopped. A murder night before last? In a temple? Perhaps the Eastern Mountain Temple, where he had heard a woman scream in the middle of the night?

It was not really any affair of his, and Kobe would not take kindly to his meddling in police business again. But Akitada had never been able to resist a mystery.

Peering around the corner of Nagaoka’s fence, Akitada made sure that Kobe was gone. Then he returned to the gate and knocked.

FOUR

Faceless Murder

After a moment, the fretted doorway opened a crack and the round, frowning face of the servant peered out.

“I am Sugawara,” said Akitada in a businesslike manner. “I must speak to your master immediately.”

This had the desired effect, for the gate opened wider and the servant let him enter. Akitada took in his surroundings. The unswept courtyard with its stone pathway was covered with fallen leaves, and the man had merely tossed a hempen shirt of mourning over his regular cotton clothes. He looked irritated, symbol of a household in disarray, but led Akitada politely enough into the house and helped him remove his shoes before bringing him to a small study in the rear of the building.

The room was bathed in diffuse light which came through the paper-covered openings of doors to the outside. Faded silk paintings and calligraphy scrolls hung against the dark wood of the walls, and carved stands displayed translucent jade bowls and vases. In the center of the room sat a thin, bent figure at a low black desk.

Nagaoka was a colorless man, gray from his hair to his dress. His clean-shaven face was ashen and deeply lined. He wore a robe of costly gray silk and was sitting hunched over, inert. When the door opened, he looked up without much interest. Even the sight of an unexpected guest caused no change in his expression. In a tired voice he said, “Not now, Sasho.”

“The gentleman insisted, sir.” The servant’s tone was aggrieved.

Akitada stepped fully into the room. “I am Sugawara Akitada,” he introduced himself formally, closing the door on the servant’s curiosity.

After a moment’s hesitation, Nagaoka took in his rank and came to his feet with a deep bow. He was almost as tall as Akitada, but narrow-shouldered and much thinner. “How may I serve you, my lord?”

“I came here for information about antiques,” said Akitada, seating himself, “but find instead that I may be of some use to you in your present difficulty.” At least he hoped he might. “Just now I met my old friend Superintendent Kobe outside your gate. He told me of the recent tragedy. You have my deepest sympathy on your loss.”

Nagaoka still stood, looking down at him with a dazed expression. His face contracted suddenly. “My brother …” he said, his voice catching. “My younger brother has been arrested for murder. If you can help, I would be…” Tears suddenly spilled from his eyes. He broke off, put a shaking hand to his face, and collapsed on his cushion. “Oh, there is no help,” he sobbed. “I don’t know what to do.”

The fact that Nagaoka seemed to grieve, not for his wife who had been the victim, but for the brother who had murdered her, struck Akitada as strange. When Nagaoka finally stopped weeping and dabbed his face with a piece of tissue, Akitada said, “May I ask where the murder took place?”

Nagaoka raised reddened eyes to his. “In the Eastern Mountain Temple. They were on a pilgrimage.”

Akitada had expected it. The complexities of fate always had a way of catching him. The rains which had brought him to the Eastern Mountain Temple for the night of the murder, the old abbot’s rambling talk, the hell screen, and his frightful dreams of screaming souls had all inescapably led him to this moment in Nagaoka’s house. He felt a shiver of dread run down his spine.

He asked Nagaoka, “Why do you believe that your brother is innocent?”

Nagaoka cried, “Because I know him like myself. He is incapable of such a crime. Kojiro is the most gentle of men. Since he remembers nothing of the night and does not know how he got into my wife’s room, he should not have confessed to something he did not do.”

Akitada reflected that a loss of memory hardly constituted innocence, even if it was genuine, but he only said, “Perhaps you had better tell me his story.”

But now Nagaoka balked. “Forgive me,” he said, “but why is it that you are interested in my family troubles?”

“Not at all. I happened to spend the night at the temple and may have seen or heard something which could be of use to you and the authorities. Besides, I am fascinated by complicated legal problems and have had some luck in discovering the truth on past occasions. In fact, that is how Superintendent Kobe and I met several years ago. He was a captain then, and I served in the Ministry of Justice. I am sure he will vouch for me.” Akitada had some doubts about this, but his curiosity about the Nagaoka murder was thoroughly aroused. “Suppose you start by telling me a little about your wife and your brother.”

Nagaoka had listened with growing amazement. Now he nodded. “Yes, yes. Let me see. My brother is much younger than I, and more strongly built. He has an intelligent, cheerful look about him. Everyone takes to him right away.”

Akitada nodded. “It sounds like a young man I saw when I first arrived at the temple gate. The lady with him was veiled.”

“My wife was wearing a pale silk robe embroidered with flowers and grasses. She, too, is … was young.”

“Quite right. They had arrived just before I did. I am afraid we did not exchange many words.”

“What a coincidence!” Nagaoka said, shaking his head. “That gown … I had just given it to her. She died in it. When I saw her, her face was … disfigured, but she was very beautiful.” He shuddered. “It is most kind of you to offer help. My brother and I…” His voice broke. “We are very close, and my being the elder… our father died young, and I have always felt like a father to Kojiro. This has all been most dreadful and I blame myself terribly.”

“For what?” Akitada asked, surprised, then added, “I don’t wish to pry into personal matters, but I would have expected you to be deeply grieved and shocked by the loss of your young wife. Instead you seem to be mostly troubled by your brother’s arrest.”

The antiquarian said bleakly, “Of course I am shocked by her death, but it is my brother who is alive, and he needs my help now. Besides …” He sighed deeply. “Our marriage had become a burden to both of us. Nobuko did not love me. I think she fell in love with my brother. It was to be expected. She was only twenty-five, and I am fifty. Look at me! I am an old man, a dull fellow who deals in old things. My brother is fifteen years my junior. He writes poetry and plucks the zither in the moonlight outside his room. What young woman could resist?”

Being happily married to Tamako, Akitada could not imagine what another husband might feel when his wife sought love from his own brother. It occurred to him that Nagaoka had a strong motive for murder himself. In spite of his explanations, the man’s reactions were all wrong. A husband betrayed by both wife and brother should have been furiously, even murderously angry. But this man sounded apologetic about his wife’s faithlessness and frantic over his brother’s arrest.

Nagaoka took up his story again. “I should never have married again. At least not someone young enough to be my daughter.” He moved his thin hands helplessly. “Nobuko was very lively when she lived in her father’s home. She liked to dance and sing, and they always had young people around. I had hoped that children might fill her life, but we did not have any. I found out soon that she was unhappy with me, and so I started staying away. I claimed that my work kept me busy, but the truth is I could not bear to see her so unhappy. She only cheered up when my brother came, and I was glad.” He broke off and stared miserably at one of the scrolls on the wall.

After a moment, Akitada said, “Forgive me, but are you suggesting that your wife took your brother as a lover because she was bored?”

Nagaoka looked shocked. “Of course not. They were not lovers, though I would not have objected. But Kojiro would never betray me … unless …” He flushed, then said firmly, “My brother would never knowingly do anything to hurt me, any more than I would hurt him.”

“Knowingly? People don’t commit adultery unknowingly.”

Nagaoka looked away. “I do not believe it.”

Akitada, having caught the small note of doubt, coaxed gently, “But there is something?”

Nagaoka cried, “I don’t know the full truth…Neither does he! Apparently Kojiro had been drinking heavily. When he drinks he often does not remember the next day where he has been or with whom. The constables from the pleasure quarter used to bring him home senseless. It was a great worry to me, because I was afraid that his drinking would ruin him.” He sighed. “And now it has.”

“Did your brother live here?”

“No, he stayed here only for his visits. He owns a place in the country. I helped him buy it with money from our father’s estate. He has worked hard on that land and also managed Prince Atsuakira’s estate nearby.” Nagaoka clenched his hands. “Oh, what will the prince think! And why did this have to happen now?”

“What do you mean, ‘now’?”

“Kojiro had stopped drinking. He had not touched wine in over a month.” Nagaoka looked at Akitada beseechingly. “Please understand that Kojiro’s behavior at the temple was a complete surprise. His previous drinking had been because of a romantic disappointment, and he’d got over that.”

Akitada had his doubts. A man who had spent his leisure time drinking himself into a stupor in the pleasure quarter was not above drinking in a temple and assaulting his sister-in-law. But he said only, “How did he come to be at the temple with your wife?”

“It was Nobuko’s idea to worship there. She wished to make a donation and say some special prayers because she had heard that women had conceived after reciting a particular passage from one of the sutras. I thought it was all nonsense, but she… Well, I could hardly stop her. But I did not want to go myself, and Kojiro offered to be her escort.”

“I see. And how does your brother explain the condition he was found in?”

“He cannot. He swears he only drank some tea, but…”

“You suspect he is lying?”

Nagaoka fidgeted. “No, of course not, but I don’t know how to explain it. He was found reeking of wine and there was a nearly empty pitcher of some cheap wine in the room.”

Akitada nodded. “Go on. What else does he say?”

“Kojiro remembers feeling tired and sick and says he went to lie down in his room. That is the last he remembers, until the monks broke open the door of my wife’s room and found him with her… dead.”

“Then why has he confessed to the crime?”

Nagaoka clenched his hands in helpless frustration. “Because he cannot remember what happened all those other times, he thinks he must have killed her in some sort of fit. I tried to convince him to withdraw his confession. To let the police investigate further.” He grimaced. “But the superintendent came today to tell me the case was closed and not to meddle anymore, that I’d just make things worse for Kojiro. He said the evidence is so solid against him that they must get a confession, and would use force to get it. Can they really do that?”

“Probably. Confessions are encouraged with bamboo whips.”

Nagaoka cried, “But my brother is no common criminal. He is a respectable landowner. Can’t you make them wait? There must be some explanation why Kojiro was in her room. Someone may have seen something that night.”

They were interrupted by the servant. “Will you take your rice now,” he asked, “or shall I let the fire go out in the kitchen?”

Nagaoka looked at him uncomprehendingly, then said, “Rice? Is it time to eat?”

“An hour past,” said the servant, casting a resentful glance at Akitada.

“Oh, dear.” Nagaoka looked helplessly at Akitada and suddenly remembered his manners. “Forgive me, my lord. I am afraid I lost all sense of time. Will you honor me with your company for the noon rice?”

Akitada had more questions, but they could wait. He must speak to Kobe as soon as possible. The longer he delayed, the angrier Kobe would be, and he would need the superintendent’s help if he was to help Nagaoka. Rising, he thanked Nagaoka, assuring him that he would do his best on his brother’s behalf.

Nagaoka also stood up. He looked relieved, but whether he was glad to be rid of Akitada or counted on his help was not clear. Bowing deeply, he said, “My brother and I are deeply obliged to you.”

Police headquarters occupied a city block on Konoe Avenue not far from the Imperial City. Akitada passed through the heavy, bronze-studded gate into the usual bustle in the broad courtyard. He walked to the main administration building and asked a young constable for Kobe. By great good luck, the superintendent was still there. Akitada found him in one of the eave chambers, deep in conversation with one of the jail guards. Kobe greeted Akitada with raised brows.

“Can I speak to you privately?” Akitada asked with a glance at the guard.

Kobe led him to another office, waving the occupant out. “Well?” he asked brusquely when they were alone.

“It is about the Nagaoka case.”

Kobe began to glower.

“I had no intention of meddling—I swear it—but something you said made me wonder if I might not be involved anyway.

“How so?” snapped Kobe. He had raised his voice, causing Akitada to glance nervously at the door. “What do you mean, ‘involved’? You just got back. How could you have anything to do with a local case? If this is another one of your tricks, you are wasting your time.”

“Oh, come, now,” said Akitada reasonably. “You were glad enough of my meddling the last time we worked together. I thought we had become friends.”

Kobe relented a little and lowered his voice. “Well, it looks bad when you stick your nose into police business. For one thing, it makes us look incompetent. And now that you are a private person of some standing in the government, there might be talk about undue influence.”

Akitada almost laughed. “I have standing? Heavens, Kobe, I am a nobody. I cannot even promote my own interests. And even if I had influence, you should know me better. I would never play political games.”

Kobe sighed. “All right! Never mind! Explain how you are involved in something that happened three days ago in the Eastern Mountain Temple!”

“I spent the night there and heard someone scream.”

Kobe’s jaw dropped. “What?”

“The rain forced me to seek shelter in the temple. I arrived right after a young couple. During a restless night I woke up suddenly—why, I do not know. But once awake, I knew there was a woman screaming somewhere outside my room. I ran out, but being unfamiliar with the temple layout, I got lost. The next morning I left early. At the gate I mentioned the incident to the monk on duty, and he let me have a look at a plan of the monastery. He explained that there is only a service courtyard in the area where the woman must have been, and only monks use it during the day. Also, because of the rain, they had an unusual number of overnight guests, among them a troupe of actors who had given a performance the day before, and the actors were, as I had witnessed myself, an unruly bunch. They could well have wandered all over the place with their women. At any rate, I put the matter from my mind.”

Kobe had listened carefully. “But you think it was something to do with the murder.” Akitada nodded. “Well, I don’t agree. You either dreamed the whole thing or, as you point out, it was probably some of those actors making a nuisance of themselves. But if it will make you feel better, I’ll have my men go back and check it out. Were you staying in the visitors’ quarters?”

“No. They keep apartments for special guests in one of the monastery wings. I stayed there. The visitors’ quarters were quite a long way off.”

Kobe said, “Well, there you are, then. Not anywhere near the murder site. In any case, there is no need for you to trouble with it further. You have reported it, and there the matter rests.”

Akitada protested, “But what if it was the murdered woman I heard screaming? It is certainly a strange coincidence that an actress should have screeched outside my room the same night. Isn’t it at least possible that she was not killed in her room or by her brother-in-law?”

Kobe glared. “That does not follow, and you know it.” Narrowing his eyes, he asked suspiciously, “And how do you know where she was found?”

“Nagaoka told me.”

Kobe flushed with anger. “So you went to speak to Nagaoka after all! No doubt he asked you to clear his brother.”

“He did.”

Kobe muttered under his breath and started pacing, casting angry glances at Akitada from time to time. After a few passes, he stopped in front of Akitada and asked through clenched teeth, “Did you inform him also about the scream and your theory that the murder must have happened elsewhere?”

“Of course not! I have no intention of undermining your work.”

“Hah! You have done plenty of damage already. Now Nagaoka will persist in dragging out the case. I went to tell him that the evidence forces us to put his brother through interrogations until he signs a confession. If the man refuses, he will be dead in a week.”

Akitada’s stomach lurched. “You cannot do that! Your evidence is not complete. He was asleep or unconscious when they found him. He does not remember anything.”

“That’s what he says. He was drunk. It’ll come back to him when he feels the bamboo whip.”

Akitada searched for a convincing argument and failed. Biting his lip, he tried another tack. “What does your coroner say about the cause of death?” he asked.

To his surprise, Kobe became evasive. “Nothing special. Time of death sometime during the night. They never like to be precise. In his fit of anger, the killer cut her up pretty badly with his sword. Not a pretty sight. By the way,” he added pointedly, “Nagaoka’s brother still had the sword in his hand and was covered with her blood when we found them together.”

Akitada felt his heart beating faster. “You still have the body?”

Kobe jerked his head. “In the morgue. It’s messy. You don’t want to look.”

“I do want to look. Would you show me?”

Kobe turned away.

“Three days have passed,” Akitada pleaded. “There is not much time before you will have to release her for cremation. How could my seeing her ruin your case?”

After a moment Kobe turned and nodded grudgingly. “Come on, then,” he muttered, walking to the door. “I must be mad, but there is something that’s been bothering me about that corpse. The coroner and I have an argument about the cause of death. I’d like to get your opinion. The doctor is still around somewhere, I think.”

As they passed through the hall, smiling police constables and sergeants bowed snappily to Kobe. His new status had clearly won him their respect. He passed them with a joke here or a nod there, only pausing once to request that the coroner be sent to the morgue.

They left the administration hall by the back, crossed an open exercise yard, and headed toward a series of low buildings. The morgue was the farthest of these, a small building reminiscent of the earthen storehouses of most mansions and temples. A guard stood at the narrow door. When he saw Kobe approaching, he flung it open. Kobe led the way as they stepped over the wooden threshold onto a floor of stamped earth. The bare room held several human cocoons, bodies wrapped in woven grass mats, but only one corpse occupied its center. A faint smell of death hung in the cool air but was not yet offensive. Light fell through two high windows covered with wooden grates.

Kobe went to the body in the middle of the room and flung back the grass mat covering the naked corpse of a young woman. She was on her back. Next to her lay a carefully folded bundle of clothing. Akitada recognized the material, heavy cream-colored silk with an embroidery of chrysanthemums and grasses. He had last seen it on the veiled woman in the rain outside the temple gate. The lovely fabric was stained with blood and dirt, and Akitada, having priced expensive silks for his sister, guiltily wished it had not been wasted on a woman who had first dragged it through the mud and then allowed herself to be murdered in it.

“Well?” said Kobe, when Akitada’s eyes had rested long enough on the clothing. “Look at her! What do you think?”

Akitada did as he was told. It was his second glance, and again he flinched inwardly. The first look had taken in the mutilated head and quickly escaped to the embroidered silk. The willful destruction of a part of the human anatomy which was the person’s identity, the self which he or she saw every morning in the mirror, the means by which humans are recognized for who they are and by which they express their thoughts and emotions to others, shocked even him who had seen too much of violent death. He recalled wishing to see the face of the veiled lady who had moved with such lithe grace. Now he would never know if she had been beautiful. Gone was the mouth which once had smiled at husband or lover and had spoken words of love—or hatred! The eyes would never again see the beauty of the world and mirror thoughts of happiness or sadness. Instead of a human face he saw a bloodied mask of raw flesh, the nose and one eye gone, the other covered with gore, and the mouth gaping like some grotesque wound. The memory of the horrors of the hell screen flashed into his mind. He wondered if the painter had studied his craft in the police morgue.

It had been a vicious attack. The killer must have been either demented or so furiously angry with his victim that he was no longer rational. Akitada thought of Nagaoka, the husband.

Kobe, untroubled by either philosophy or psychology, urged impatiently, “Well, come on! Or are you waiting for the coroner to tell you what happened to her?”

“Talking about me behind my back again, Superintendent?” asked a high, brisk voice from the doorway. A small, dapper man in his fifties walked in with a bouncing step. He gave Akitada a glance, bowed slightly to both of them, but spoke to Kobe in a casual, almost jovial manner. “So? What gives us the honor of a second visit, Super?”

“ ‘Us’?” Kobe grinned, raising his brows. “Have you appropriated police headquarters, Masayoshi, or just the morgue? Or perhaps you have formed a closer relationship with the late Madame Nagaoka here?”

The dapper man cackled. “The latter, of course. It is a professional bond which always develops between the coroner and the latest victim of a crime. The intimacy of my investigation has much of love and passion in it.” He winked at Akitada, who frowned back.

“I brought a friend,” explained Kobe. “His name is Sugawara. He’s the nosy fellow who likes to solve my cases. As he wanted a look, I thought you could use some help, being that you don’t seem to be able to make up your feeble mind about the cause of death.” Kobe turned to Akitada. “This is Dr. Masayoshi, our coroner.”

Akitada gave the man a cool nod. He was scandalized by the coroner’s flippant attitude toward the body of a respectable young married woman.

If Masayoshi noted his expression, he ignored it. “I’ve heard of you,” he said. “There was a great deal of talk the time you pinned a strangulation of a girl from the pleasure quarter on one of the silk merchants.”

Akitada stiffened. “Nobody pinned anything on the silk merchant. The man was guilty. It was a long time ago, and you cannot be expected to have all the facts. Also, it required no medical skills. I have since had opportunity to learn a few things from one of your colleagues, but could not, of course, match your expertise. Please give me the benefit of your opinion in this case.”

“Ah!” said Masayoshi, his eyes twinkling. “I see how it is. The superintendent has brought an ally. It would hardly be fair if I spoke first. Tell us what you think happened to her.”

Irritated by the man’s manner, Akitada said, “Very well,” and began an examination of the dead woman. Nagaoka’s wife was of average height, as he knew from having seen her at the gate, and had a well-shaped and pale-skinned body. There were no visible wounds anywhere except, of course, for the mutilated face and shoulders. Nudity of men and women was too common a sight in bathhouses, or in ponds and rivers during the summer, to trouble him as he bent closer to scrutinize the well-shaped legs and arms, the small, firm breasts, flat belly, and rounded hips. “She was young and attractive, perhaps in her early twenties, and has led an active life,” he said, and moved to study the soles of her feet and the palms and fingers of her hands. “Her skin is too smooth and white for a peasant,” he noted, “and her hands and feet are well cared for, but…” He felt the upper arms and thighs, pursed his lips, and straightened up.

Kobe met his eyes impatiently. “Come on! What about the way she died?”

Akitada glanced at the terrible wounds made by the killer. Several of them could have been fatal. They had obliterated the face, nearly severed the neck, and left deep gashes in her shoulders. “The cuts were made with a sword, I believe. No knife could have left such deep, hacking gashes, but sword wounds look like that. I have seen many of them.” Unwelcome memories rose; Akitada pushed them firmly aside and knelt again to look more closely at the wounds. “Strange,” he muttered. “She must have been prone. Whoever wielded the sword stood over her, for the cuts are deeper at the top and quite shallow lower down. Also the swordsman, or perhaps it was a woman, must have cut the throat deliberately, for that required a change of direction.”

Kobe said, “Hah!” and exchanged a triumphant glance with Masayoshi, who chuckled and asked, “Anything else?”

Akitada was still looking and probing with his long index finger. The wounds of the face gaped, puddles of dried blood mingling with cartilage here and there, and pieces of bone protruded whitely from the raw flesh. One eye was closed; the other had disappeared completely in a mass of bloody pulp. Where the lips had been, broken teeth glimmered against the coagulated blood which filled the mouth cavity. It was no longer a human face. Akitada controlled a shudder.

“There is not enough blood,” he said after a moment, and looked up at Masayoshi, his face suddenly tense. “That means she was already dead when she was hacked to pieces, doesn’t it?”