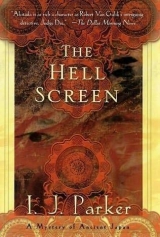

Текст книги "The Hell Screen"

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

It was a very small act of defiance, for otherwise Akitada mourned Lady Sugawara publicly with all the expense and proper behavior of an only son.

Akitada saw that Yori’s eyes were large with excitement as he watched the flames of the funerary pyre being lit by one of the monks. When the moment came, Akitada rose and ceremoniously placed Lady Sugawara’s favorite possessions, her elegant toiletry boxes, carved rosary, zither, and writing utensils, along with the token coins to pay her way in the other world, into the flames.

The monks began their chanting again, and the flames rose higher, crackling softly, sending a long column of darker black smoke into the night sky, slowly obscuring the stars. The fire consumed symbols of emptiness, for life was no more than a wisp of dark smoke fading into night.

Yori fell asleep after a while, and his father pulled him close into his protective arm. Across the way, in the women’s shelter, someone sobbed loudly. Akiko, no doubt, Akitada thought wryly. She always knew what was expected of her in public. Toshikage half turned to cast anxious looks that way, and Akitada thought, not for the first time, that Akiko had been very lucky to have found such a husband.

Of course, Toshikage’s problem also affected her, and if Akitada was right in his suspicions, Akiko was the cause of it. Either way, he had a duty to help Toshikage. But this death had made things very awkward. None of them could go about naturally for the next seven days. They were, for all intents and purposes, housebound. And even after that Akitada and his sisters would have to observe restrictions of normal activities for another six weeks, until the ceremonies of the forty-ninth day had been completed and the soul of the deceased had departed the world.

On the positive side he need not worry about being called to court for the coming weeks. But meanwhile Toshikage’s situation was pressing. For all they knew, the director of the Bureau of Palace Storehouses was already planning an investigation into Toshikage’s stewardship. It was dangerous to let another day pass without taking action, and Akitada pondered this problem as the hours passed slowly.

The fire began to burn out after a while, and more wood was added to the pyre. The air became saturated with the smell of wood smoke and incense and, very faintly, of burnt flesh.

Tora came quietly to take the sleeping child to his mother. When he left, Toshikage whispered, “Do you think the ladies are warm enough?”

Akitada nodded and glanced at the sky. “It will be dawn soon,” he murmured. “Come to my house to warm up before returning home.”

Toshikage nodded gratefully.

Akitada thought how easily the words “my house” had come to his lips. It was truly his home now, no longer poisoned by memories of his parents’ supposed rejection of him. He recalled his father’s stern mien, so harsh and frightening in his childhood memories, and tried to see it as a mask put on to reassure a jealous wife that he felt no love for this son and merely tolerated him. And he thought much of the young woman who had been his mother. How short her life had been! Had she loved his father? If she had lived, would his life have been different? He felt in his heart that his mother would have loved him.

With the first light of the dawn, the monks stopped chanting. They went to pour water on the smoking remnants of the fire, then sprinkled the ashes with rice wine. Later they would collect the bones and inter them near his father. Akitada wondered where his mother’s remains lay. The mourners straggled to their feet stiffly, and attendants went to get the litters ready for the women. Yori, still asleep, would ride with Tamako, but Akitada and Toshikage walked back side by side.

On the way from the cremation grounds, they stopped to perform the ritual purification at one of the canals which crisscrossed the city. The water was icy, and they hurried their ablutions.

“A fine funeral,” remarked Toshikage, wrapping his wet hands into the full sleeves of his gown.

“Yes. It went very well,” replied Akitada. One said such things, when there was nothing else to say. Certainly Toshikage knew better than to assume that Lady Sugawara was sincerely mourned by anyone, including his wife Akiko.

But this did not stop Akiko later from reciting lines of poetry about the melancholy event when they gathered for some hot rice gruel and warm wine. She dwelt with many sighs on the emptiness of life, and spoke of that sad period spent in “a night of endless dreams” before entering “the dark path” into death, meanwhile eating and drinking heartily between moments of inspiration.

Toshikage watched her complacently, remarking that the enforced period of mourning would give him a chance to see more of his wife. “I shall not be expected at the office,” he said, adding with a distinct note of fatherly pride, “Takenori is quite capable of carrying out my duties for the next week. The boy is really a great help to me these days.”

Akitada went to visit Takenori later that day. It was early afternoon, and he had had only a few hours of sleep. The weather was still wintry, but the sun shone brightly and warmed the air. He had dressed in a plain gray robe and formal black cap which could pass for either mourning or ordinary wear, but wore the wooden taboo pendant attached to the cap. It would stop casual acquaintances and strangers from engaging him in conversation on his way across the palace grounds.

He left the house quiet and shuttered, the large taboo sign at the gate warning visitors away from the contamination that a recent death placed on a household. The morbid presence of these reminders of death cast a dark mood over his errand. Much—no, everything—depended on Toshikage’s son, and their previous meeting had not been encouraging.

When he reached the Greater Palace, the streets and buildings of the large enclosure hummed with activity: officials and clerks bustled about and messengers ran to and fro, carrying documents and records; the Imperial Guard made a splendid show at the gates, and performed a snappy drill in front of their headquarters. Akitada had his private doubts about the guard’s effectiveness in case of an armed attack on the emperor. It had become a much-sought-after profession for the sons of minor nobles and provincial lords who wished to give their offspring exposure at court. But the guardsmen were young and looked sharp enough in their stiff black robes and feathered hats as they rode their horses in tight circles and twanged their bows.

The Bureau of Palace Storehouses was in a large building immediately to the north of the imperial residence. It contained not only offices but storage for the treasures belonging to the sovereign and other members of the emperor’s family. The entrance was guarded by two young guardsmen who cast sharp glances at Akitada, noting his cap rank as well as the taboo marker, and let him pass.

Akitada was not prepared to answer searching questions about his identity and business there, so he was pleased to find Toshikage’s name on a door almost immediately. He knocked, heard a firm young voice inviting him in, and entered, closing the door behind him.

Takenori was seated at his father’s desk, bent over a ledger into which he was making entries. When he saw who had walked in, he froze, brush in hand, and stared openmouthed.

“Good afternoon, Takenori,” said Akitada pleasantly, seating himself across from the young man.

Takenori dropped his brush into the water container and scrambled to his feet to bow. “Good afternoon, my lord,” he gasped. When he straightened up, he still looked utterly confused. “Er, allow me to express my condolences, my lord,” he stammered, then ruined the conventional courtesy by blurting out, “But your honored mother’s funeral was only last night. My father is at home because of it. How is it that you are here?” He stopped and, with sudden panic showing in his face and voice, cried, “Something has happened! Is it my father? Is he ill?”

Akitada noted this reaction with approval and relief. So the young man did care about his father! That made things easier. He said, “No. Nothing of the sort. Please be seated. I had hoped to have a chat with you while your father is elsewhere, that is all.”

Slowly Takenori sat down. His brows contracted, and some of his former antipathy returned. No doubt he wondered what could be of such importance that Akitada would break the social and moral rules of mourning so flagrantly to consult him personally.

Akitada smiled at him. “Though I have not known your father very long, you should know that already I feel a great affection for him.”

Takenori barely suppressed a look of distaste. He clearly did not believe Akitada, but said politely enough, “Thank you. You do us a great honor, my lord.”

“And that is why I am very concerned about the missing items. I think you must be aware of the seriousness of your father’s situation. Should he be found guilty of this theft, he along with his whole family would be exiled to some very unpleasant, faraway province.”

Takenori flushed. “My father is innocent and will prove it.”

“Furthermore,” continued Akitada as if Takenori had not spoken, “his property, large though it is, would be confiscated and all of you, you and your brother included, would be penniless.”

Takenori became quite still. He looked at Akitada for a long time, clenching and unclenching his hands. Then he asked harshly, “Did you come here to tell me that you wish my father’s wife, your sister, to return to her family because you fear for her future?”

Akitada raised his brows. “That was not only rude, but silly,” he said. “I would not discuss such a matter with you, but with your father.”

But Takenori had worked himself into a seething temper. “Well, if it was not your intention to dissolve the marriage,” he said, “you must forgive me, for I cannot imagine that anything but an urgent crisis affecting your own family could bring you out during the ritual seclusion. And what else could you have to discuss with me?”

Akitada cocked his head. “Come, now, Takenori, we both know who took the missing objects, don’t we?”

Takenori stared back at him. He slowly turned pale. “Wh-what do you mean?”

“Where are they? In your room in your father’s house? Or somewhere in this building?”

“Why would you accuse me? Anyone could have stolen those things.”

Akitada noted that so far the young man had avoided an outright denial. He pressed his advantage. “No. Not anyone. Only you or your father could have removed anything from this place and brought it to your house, and I saw the figurine in Akiko’s room myself. No one else in that house had access to the treasures, and no one here had access to her room. As I said before, I have come to like your father a great deal. He is as incapable of theft as of lying about it afterward. You, on the other hand, are a stranger to me.”

Takenori stared back at him. The color came and went in his pale face.

“I have wondered a great deal lately what sort of person you are,” continued Akitada thoughtfully, folding his arms across his chest and studying the young man. “Are you, for example, greedy for wealth and power? Or do you feel such resentment toward your father that you are willing to sacrifice your whole family and yourself to punish him for putting you and your brother aside for the child my sister bears? Or perhaps you are merely playing some sort of childish game by which you hope to break up your father’s marriage to my sister?”

Takenori flushed scarlet and bit his lip.

“Ah, so that was it. I thought so. Well, it won’t work, young man. You are playing with fire. The other day you hoped to provoke a scene between your father and his superior by placing the emperor’s figurine in my sister’s room, thinking that your father would take the director there to show him the new screen. If I had not happened to visit that day, disaster would have struck. Your father would have been arrested. How did you hope to extricate him from the trap you had built?”

Takenori cried, “They would not have dared arrest him. He does not need to steal. He is rich. It would simply have been ascribed to thoughtlessness as before. But you would have heard about it and thought he was guilty. And she would have left my father.”

“I see. Tell me, why do you resent my sister so much?”

Takenori looked away. “I have served as my father’s secretary for several years now and I saw the marriage settlements. My brother and I plied the matchmaker with wine, and he told us all about it. Your sister married my father only for his money. Your mother and your sister apparently were quite frank about it during the negotiations.” He gave Akitada a sudden, bitterly resentful look. “Cruelly frank, I might add.”

Akitada grimaced. That had the ring of truth about it. “Does your father know about this?”

Takenori flashed, “Of course not. We would never tell him what was said. My brother and I tried to talk Father out of this marriage, tried to make him renege on the contract, but he refused. When my brother became too insistent, my father got angry and sent him away.” He clenched his fists and added bitterly, “He sent his own son away to die. I know your sister suggested it to him, because we stand in the way of her unborn son. When I saw what had happened to my brother, I decided to become a monk. At least a monastery is safer than a war.” He buried his head in his hands.

Akitada knew only too well the pain of feeling rejected by a parent. “You do not really desire the monastic life, I gather?” he asked gently.

There was no answer.

Akitada sighed. “My sister has her faults,” he said after a moment, “but she had nothing to do with your brother’s decision. Neither did your father. He told me that he tried to talk Tadamine out of it. It appears that your brother is just such a hothead as you, but unlike you he is enamored of soldiering. Unfortunately, since you both made such drastic changes in your lives, Akiko has come to look at the unborn child as the natural successor to your father. It may, of course, be a girl, but there will be other children. Still, if my sister’s children succeed to the entire estate, it will be no one’s fault but yours and your brother’s. I suggest you reconsider your own plans and urge your brother to return. He can always carry out his martial activities here as a member of the Imperial Guard.”

Takenori raised his face from his hands to stare at Akitada. “B-but I thought,” he stammered, “that you and she wanted it this way. I… I assure you, the marriage contracts are very specific about her rights.”

“I know all about the contracts. I signed them and provided my sister’s dower. However, I had nothing to do with the terms. My late … mother was a shrewd businesswoman when it came to providing for her daughter. I may not approve of all that passed in my absence, but it is right that Akiko and her unborn child should be secure if something were to happen to your father. However, that does not mean that anyone wished you and your brother to be disinherited.”

“Oh.” Takenori looked suddenly lost, uncertain about what had just taken place, and not yet believing in his good fortune.

Akitada rose. “I cannot stay. Someone might come in, and I have no desire to be caught in explanations. Your plan was quite irresponsible and extremely dangerous. I trust that you would not have let it come to the point of your father’s arrest?”

Takenori started. “Oh, no! I would have confessed immediately.”

“Well, whatever you may have thought, your father loves both his sons and is very proud of you and Tadamine. It would hurt him badly to know what you did. That is why I had to come to speak to you without his knowledge. You will keep the matter to yourself, and I rely on you to return the missing items immediately to their proper places. Find a plausible explanation for how they came to be misplaced.”

Takenori scrambled to his feet. “Yes. Right away. I… am so sorry about all this. You were very good to …”

But Akitada had already slipped out of the door.

Outside, the same winter sun shone brightly. Akitada blinked his eyes against the brightness. The day no longer seemed sad to him. If life was a path through darkness into death, then at least it was good to extend a helping hand to another traveler. Besides, the past had taught him lessons which would light the way in the future.

ELEVEN

Miss Plumblossom

As it turned out, it was a whole week later before Tora and Genba were free to visit the city. They were by now well into the last month of the year, and appropriately the weather was bitter cold. There had been too many chores to do in the sadly understaffed household. But after some of the most urgent—and quiet—repairs had been made, even Akitada could see that hammering and sawing were not appropriate in a house of mourning, at least not until the taboo tablets had been taken down from the gates.

The pair were on their way toward the riverfront in the southern part of the capital. It was late afternoon, and already the light was fading. The weather was not only frigid, but a heavy gray cloud cover threatened snow. They wore their quilted robes and lined boots and stepped out briskly, eager to sample the night life.

Their way took them through residential streets, quiet and sedate, lined with tall plaster walls which hid low-roofed pavilions in large tree-shaded gardens. Here servants swept the street in front of important double gates, and litters picked up the inhabitants for their errands.

The farther south they walked, the more the character of the streets changed. The houses moved closer together and added second stories whose roofs almost touched, and the gardens shrank to a few trees which grasped for the leaden sky with skeletal branches through narrow openings between roofs. Here the merchants lived, doing business in the house which they occupied with several generations of their families. Their wives or kitchen maids swept the street here, and customers and apprentices hurried in and out of many narrow doors.

Genba attracted the usual admiring stares. His size made him noticeable, for he was half a head taller than Tora, who was no midget himself, and much heavier. In fact, Genba was so big and broad that his wide shoulders and barrel-like torso resembled more a moving tree trunk than a man. His gait, developed after years of lifting weights and wrestling, had something to do with this also. He moved from the hips with a wide-legged stride, placing each foot firmly and deliberately before shifting the rest of his body, causing him to sway ponderously from side to side. The wrestler’s walk is easily recognized, and wrestlers were universally idolized. No wonder, then, that people stopped and stared after them.

He looked about him happily, like a child on an excursion. Smiling broadly at people, he remarked to Tora, “It’s getting close to the hour of the evening rice, isn’t it?”

“Too early.” Tora was nearly as cheerful as his companion. “Let’s go through the pleasure quarter. Maybe some of the girls are out.”

“Not in this weather,” said Genba firmly. “People stay in and put some nourishing hot food inside themselves.” He gave Tora a measuring glance and added, “How about some nice restaurant? The girls will be there on a day like this.”

“Hmm,” said Tora.

They reached the Willow Quarter, but as Genba had predicted there were only a few customers hurrying to assignations, and no women at all. Tora walked along the street, peering into each grated window, disappointed to find it closed by paper screens or curtains. .

He proposed stopping in the quarter for a cup of wine, but Genba had more substantial things in mind. “The master wants to know about the actors. Let’s go where the actors eat!” he said.

They had to leave the protective streets and alleys of the city to reach the windy riverfront. A cold blast of air from the mountains in the north blew up the skirts of their robes and sent icy needles of air through their leggings and down their collars. Heavy black clouds were gathering above Mount Hiei, and the Kamo River moved choppily.

“Whew! Bad weather coming!” Tora peered down the street which followed the river. Fishermen’s huts and warehouses gave way to long rows of eateries overlooking the broad gray waters of the river. Like the icy wind, the river came from the mountains in the north and flowed in a southerly direction past the capital, forming its eastern boundary. It was here, along the riverfront, that Tora and Genba hoped to find news about Uemon’s Players.

Tora was for putting his head into every wineshop and eatery they passed to ask for them, but Genba made for a large building with a nondescript exterior about halfway along the block. Over its low door hung a badly written sign which read “Abode of the River Fairies,” and it seemed to be doing an excellent business. A low hum of voices emanated from the door and the screened windows. A rich smell of cooking fish emanated also and started Genba’s nostrils quivering and his lips smacking in anticipation.

Their arrival in the dim, lamp-lit room went unnoticed. Most of the space was taken up by rough tables and wooden benches, the kind one usually finds outside for the convenience of travelers or people in a hurry. Their practicality here was due to the fact that the establishment had a dirt floor. The tables and benches were arranged around a cooking pit in the middle of the room. Several huge black iron cauldrons simmered over a charcoal fire, watched over by a bare-chested, muscular fellow with a bandanna tied around his hair and sweat glistening on his face and chest. From time to time he paused his stirring to use a huge ladle to fill a bowl held out by one of the waiters. A lively exchange of jokes passed back and forth between this cook and some of the guests.

Tora paused to study the women, but Genba had no eyes for them. Smiling happily, he seized Tora’s elbow and made for a table close to the steaming cauldrons, where he slid onto a bench already occupied by an elderly man who was staring morosely into his wine cup.

“May two thirsty fellows join you, brother?” Genba asked, using the local dialect. The man was in his fifties and wore a stained brown cotton robe. His thinning gray hair was stringy and unkempt, and a heavy stubble on his chin showed that he had not bothered to shave for several days. Tora took him for the neighborhood drunk.

The man looked up at them with bleary, bloodshot eyes. “Why not?” he asked, his voice cracked and the sounds slurring. “Drinking alone causes depression, and depression is unhealthy, as the ancients tell us.”

Tora and Genba looked at each other. The man’s speech was educated, incongruous in these surroundings and in someone of his appearance. The drunk seemed to read their thoughts, because he suddenly gave them a crooked grin and lifted his cup. Emptying it, he waved it toward the muscular cook and cried, “More of your elixir of happiness, Yashi! I feel the blue demons coming on again.”

Blue demons? It crossed Tora’s mind that the man might be one of those soothsayers who sell their spells in the marketplace. Some of them claimed to be wizards who could call up demons whenever it pleased them. He eyed the drunk warily.

The cook glanced over, took in the two newcomers, and shouted back, “You’ve had enough! I’m not putting you up again. And your master’ll have your hide if you spend another night in the gutter and get killed.”

This ridiculous threat reassured Tora. The man was only a servant after all.

The elderly man, however, glared at the cook and rose, swaying a little. “My good man,” he said with enormous dignity, “I resent your inference as much as your tone. I’ll have you know I am no servant. Indeed, my education makes me the equal of the gentleman lucky enough to enjoy my services at the moment.” He then spoiled the gesture by belching and tipping backward so suddenly that Genba had to jump up to catch him.

“Thank you, my humble friend,” the man muttered, feeling about in his sleeves. “A touch of dizziness. It is a warning I recognize.”

“A warning of what?” asked Tora.

“Ah,” said the man, glancing across at him from watery eyes, while still feeling about in his robe. “You and your friend here are both too young to understand the sorrows of an academician come down in the world. You have not lived long and painfully in a country inimical to intellectual pursuits. What I meant was this: I always get dizzy when the blue demons are imminent. And now I seem to have misplaced my money, too.”

Tora cast a glance around the room for the blue demons, but saw only ordinary people who were more interested in their food than the odd man at their table. “Where are these devils? I don’t see them.”

Genba chuckled. “He means his sad thoughts for which he drinks. Perhaps you would care to join us, sir,” he said to the elderly man, pulling out a string of coppers. The elderly man bowed his acceptance and Genba waved down a waiter. “Here, bring enough wine and food for the three of us!”

“Most kind of you to help a stranger in distress, sir,” said the man. “Allow me to introduce myself. My name is Harada, doctor of mathematics, but at present estate manager for my colleague, Professor Yasaburo, in Kohata. May I know your honorable name and dwelling so that I may repay the debt?”

“I’m Genba and my friend is Tora. But what are a few coppers between fellow visitors to the capital? We hate to eat and drink alone.”

Harada bowed, expressed himself charmed to make their acquaintance, and offered himself as a guide to the local attractions, which he had just begun to describe when the waiter returned with a jug of wine, two more cups, and a large platter of pickled radish. Mr. Harada poured, spilling only a little, and Genba sampled the radish.

“So you’re really just an overseer of a farm?” Tora asked, still thinking about the blue devils. “I mean, you don’t tell fortunes and call up spirits on the side?”

The cook shouted across, “The only spirits he calls up are in his cup. He’s a hard drinker.”

Harada, far from taking offense, said, “On the contrary, my friend of the steaming pots. Drinking is the easiest thing I do. The world rests heavily on my shoulders and the worries of my days fray at my nerves.”

“And the wine makes the world go round till you’re too dizzy to see straight,” grunted the cook, ladling out a large platterful of steamed chunks of fish and vegetables. “See,” he said to Tora and Genba, passing the bowl to the waiter with a jerk of the head toward their table, “it’s like this: When he’s out of sorts, he drinks. After the first cup he feels more like himself. So he has another and now feels like a new man. But the new man wants to drink, too, and so he goes on drinking till, pretty soon, he feels like a babe … bawling and crawling all the way home!”

Laughter greeted these witticisms. When Harada protested, “I drink only to calm myself,” one of the guests shouted, “Yeah! Last night he got so calm he couldn’t move! Ho ho ho!”

“Fools!” muttered Harada. He pushed away disdainfully the bowl of fish and rice the waiter placed before him and instead refilled his cup from the pitcher. “The Chinese poets understood about wine!” he said, holding up the cup and squinting at it. “It frees a man’s genius from the shackles of physical existence.” He emptied the cup. “ ‘I will fill my cup and never let it go dry,’ said Po Chü-i. And Li Po said, ‘I can love wine without shame before the gods.’ Li Po knew there’s no point in explaining this to a sober man. Poets must nourish their souls, not their bellies.” He glanced around the table and saw that both Tora and Genba had their noses deep in their bowls of fish stew. His nose twitched, and he eyed his own bowl thoughtfully for a moment, then reached for it.

Genba was emptying and refilling his own bowl with such speed and complete enjoyment that his lip-smacking and belching attracted the pleased attention of the cook, who promptly sent along a heaping platter of steamed eel, compliments of the house.

“So you’re a poet?” Tora asked their companion. “I thought you just said that you manage a farm.”

“Not a farm. An estate.” Harada looked at him blearily. “You may not be aware of it, young man,” he said with a fruity belch, “but poets have never enjoyed a regular income without a generous p-patron. P-professor Yasaburo, my old friend and classmate, is the closest I could find to a p-p … magnanimous p-erson, and he makes use of my many other skills as he has need of them.” Taking another gulp from his cup, he belched again, and added, “At the present time, you behold in me an ambassador of good will, a bearer of happy tidings, a p-purveyor of the substance which makes even the dull p-pragmatists happy. In short, I have completed an errand of mercy.” With a great sigh, he folded his arms on the table, laid his head on them, and went to sleep.

Tora, who had listened with only half an ear, now turned to Genba. To his surprise, Genba had stopped eating. He sat, slack-jawed, staring past Tora’s shoulder, an expression of stunned amazement on his face. The platter of eels in front of him was barely touched, and he still held his chopsticks with a juicy morsel suspended halfway to his open mouth.

Tora looked to see what had shocked Genba into immobility. The restaurant was full of people. Behind them six men, of the ordinary riverfront variety, were exchanging stories over their wine. Near a pillar, several women were eating fish stew and chattering among themselves. Against the back wall, an old man presided over a table filled with members of his family. And near them a husband and wife were engaged in an argument. Tora could not see anything likely to cause that look in Genba’s eyes. He reached across to take the chopsticks from Genba’s rigid fingers. “What are you staring at?”

Genba jerked. “Huh? Oh!” He blushed scarlet. “See the young lady over there? She’s the most stunning creature I’ve ever seen.”