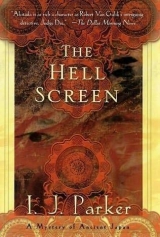

Текст книги "The Hell Screen"

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

NINETEEN

The Temple of Boundless Mercy

Saburo opened the gate and helped Akitada with the semiconscious Harada. When they had him standing on wobbly legs, Harada mumbled, “Sorry, must’ve had a drop too much. Head hurts,” and pitched forward. Akitada caught him and picked him up bodily. Harada weighed little, even with his assorted blankets.

“Get Seimei and send him to my room,” Akitada told Saburo, and carried Harada into the house.

In his study, he laid him down. Harada opened his eyes and blinked at him. “What… where … ?”

“Don’t worry! My secretary is quite good with herbal remedies, and so is my wife. They will have you feeling better in no time.”

“Tha’s very good of you,” mumbled Harada. He looked at Akitada uneasily. “Er, who are you? I seem to have forgotten.”

“Sugawara. You are in my house. I brought you here because you seem a bit feverish.”

“Hmm,” said Harada, and fell into a dry coughing fit which left him shaking and gasping.

The door opened and Seimei came in.

“Another patient for you,” said Akitada. “This is Professor Harada. He was manager for Nagaoka’s father-in-law, Yasaburo, who was arrested for Nagaoka’s murder. Our guest is a witness in the case. I brought him here because he is too sick to go anyplace else.”

Seimei was immediately all interest and attention. He knelt, greeting Harada with a bow, before peering at his face intently. Harada peered back. Seimei bowed again and touched Harada’s forehead. “A fever is burning your life force and you must be put to bed immediately, sir,” he informed the sick man. Then he turned to Akitada. “Shall I put Professor Harada in Miss Akiko’s room?”

“Yes. And see what you can do for him.” Harada had closed his eyes and was either asleep or unconscious. Akitada took Seimei aside and gave him a sketchy outline of Harada’s misfortunes, adding, “He has suffered more misery than one man deserves.”

Seimei shook his head with pity, but remarked, “As to what he deserves, sir, we do not know what he may have been guilty of in his previous life.” Seimei was a strong believer in karma as the ultimate leveler of human lives, punishing transgressions and rewarding virtues in subsequent lives.

“How is Tora?” Akitada asked.

Seimei smiled. “Much improved, though he won’t say so in front of the ladies.”

“The ladies?”

“Oh, yes. He has visitors every day.”

Akitada scooped the sick man up again, and carried him to another wing of the house where his sister Akiko’s room had stood empty since her marriage to Toshikage. There, Seimei spread bedding from a trunk. Together they divested Harada of an odd assortment of patched blankets and robes and tucked him under the quilts.

The small room Tora shared with Genba was crammed full of people. Tora, covered by a quilt and leaning on an armrest, reclined on a mat in its center. Next to him sat Miss Plumblossom, enthroned on an upturned water barrel on which someone had placed one of the silk cushions from Akitada’s room. Apparently she refused to sit on the floor like everyone else. Slightly behind her was her maid, her scarred face hidden behind a fan, and on Tora’s other side knelt a very pretty young girl with sparkling eyes. Genba’s bulk filled the rest of the room. All of them looked up at Akitada’s entrance, smiled, and bowed.

“Well!” Akitada looked around. “I hope I see you all well. Especially you, Tora.”

“Pretty well, pretty well,” Tora said with an expression of patient suffering. “The company helps, but the nights are bad, and I can’t seem to move without much pain.” The pretty girl by his side took his hand and stroked it, murmuring, “My poor tiger.”

The rascal, thought Akitada, and sat down. He kept a straight face and told Miss Plumblossom, “I am happy to see that you have made your peace.” Sitting down had put him at a distinct disadvantage, because the formidable Miss Plumblossom now towered over him.

She was untroubled by the impropriety. “The four of us have come to an understanding,” she informed Akitada, and smiled with fashionably blackened teeth. “Yukiyo, the foolish girl, will make up for falsely accusing poor Tora by helping him find the slasher. Between us we’ll get the bastard, if it’s the last thing we do.” She nodded emphatically and her red hair ribbons bounced.

Akitada looked at Tora, who looked back uneasily. “It’s what I’d planned to do all along, sir,” he pleaded. “In fact, that’s one reason I went to Miss Plumblossom’s. I’ve finally got a case of my own to solve.”

Akitada opened his mouth to point out some small problems—such as the fact that Tora needed rest, or that, once he was well, he had certain duties to perform, or that the slasher had so far escaped the superior manpower of the police as well as the watchful eyes of people. Something about Tora’s face made him keep his thoughts to himself. “Excellent!” he said heartily. “I wish you the greatest success. Given your experience and special talents and Yukiyo’s description of the man, you will triumph where Superintendent Kobe has failed.”

Tora flushed with pleasure, but Miss Plumblossom said, “The silly girl says she couldn’t see in the dark. All she’s sure of is that he was smallish and thinnish but very strong. Humph!”

“After such a vicious attack, it is a wonder she recalls anything. Perhaps in time she will remember more.”

The maid mumbled something.

“Oh, yes. She says she smelled him,” interpreted Miss Plumblossom with a toss of her head. “As if we could go around smelling people.”

“What sort of smell was it?” Akitada asked, interested in spite of himself.

Tora moved impatiently. “Never mind, sir. We’ll get it all sorted out. How was your trip? Catch any murderers?”

“Superintendent Kobe has arrested Nagaoka’s father-in-law, and I brought home a guest, a Professor Harada. He used to work for Yasaburo. He is pretty sick, but may be able to give us some information. Seimei is tending to him now.” Akitada looked curiously at the pretty girl. “Is this young woman by any chance a member of Uemon’s Players?”

“Yes, Gold’s an acrobat. She’s fantastic.” Tora smiled proudly at the girl, who returned the adoring look.

“In that case, Gold,” said Akitada, “you may be able to answer a question. You stayed at the temple where the woman was murdered, didn’t you? On the fifth day of last month?”

“Yes, sir. Tora’s already asked me about that. I saw nothing, and neither did any of the others, sir.”

Akitada hid his disappointment. “You did not leave your room after dark?”

“No. We had performed that afternoon and I was tired. Besides, it was raining.”

“You slept alone?”

“No. My sister and Ohisa shared the room. They came to bed later, but my sister also saw nothing.”

“And Ohisa?”

“Ohisa took off before either of us awoke.”

“Took off?”

Gold made a face. “Ohisa used to be Danjuro’s girl. Danjuro is our lead actor, and all the women are wild about him.” Tora glowered and she added with a smile, “Except me. I can’t stand the arrogant bastard. Anyway, he dumped Ohisa and she left in a snit, just like that. We would’ve been short a dancer if Danjuro’s new girlfriend hadn’t stepped in.”

“And none of the others saw anything suspicious?”

She shook her head. “They would’ve told me. We talked about the murder all the way back to the capital.”

Akitada thanked her and turned to Genba. “I trust everything was quiet in my absence?”

Genba nodded. “But there was an odd little man here a little earlier. He asked for you. Something about a screen he’s supposed to paint for your lady, so I took him to her. I hope that was all right?”

“Heavens, Noami!” Akitada jumped up. “He is a very unpleasant person. I had better see him before he upsets my wife.”

He met Tamako in the corridor outside her quarters. She had heard of his arrival and was coming to look for him.

“I am glad you are back safely.” She bowed in her restrained and formal manner, but her eyes searched Akitada’s face.

“I looked in on Tora first and found him surrounded by admiring females, plotting how to catch the slasher.” Seeing her incomprehension, he explained, “A man who has been mutilating and killing young women in the city.”

Her eyes grew round. “How very horrible,” she breathed. “I had no idea such things were happening. Is it safe to go out?”

“Safe enough, provided you go in the daytime, take a maid with you, and don’t venture into unsavory parts of town. By the way, I brought you another patient.” He explained briefly about Harada.

She nodded, then took his arm. “Come! I have someone waiting to talk to you. The painter of the pretty scroll has called. I left him giving a drawing lesson to your son.”

An irrational fear seized Akitada. “You left him with Yori?”

But the scene which met his eyes was harmless enough. The defrocked monk, dressed in a decent gray robe, his short hair brushed back, knelt next to Akitada’s son. Both held ink brushes and were bent over a large sheet of paper.

The boy looked up and a broad smile lit his face. Jumping to his feet, he ran to his father and wrapped his arms around his thighs. “I’m painting,” he cried. “I painted cats. Come see!”

Akitada nodded to Noami, who bowed with unexpected politeness.

“I called, sir,” he said in his grating voice, “to see if you wished me to proceed with the screen for your lady. Since you were not here, it was my great fortune to meet the beautiful lady herself and your charming son.”

The compliments were courteous, but Akitada did not want this man near his family. “It was good of you to come,” he said brusquely, “but we have not really had time to consider the matter.”

Yori tugged at his sleeve.

“I was perhaps a little unreasonable about the price,” Noami suggested.

Still easily shamed by money problems, Akitada felt the color rise to his face. “No, no. I have been too busy to consider and will let you know when we make up our minds.” He hoped Noami would get the idea that the visit was over.

But the painter lingered. “Young Yori has something to show you,” he reminded Akitada.

Reluctantly Akitada allowed his son to draw him over to Noami’s side. The sheet of paper was covered with pictures of cats. Some were admirably true to life, their catlike postures sketched with consummate skill: a cat jumping for a mouse, a cat staring down into a fishbowl, a cat toying with a beetle, a cat hissing, and a cat eating a bird. The others were childish copies by Yori, painstakingly executed, the black-on-white scheme enlivened by vivid touches of red.

“Your son has a lively sense of color,” Noami commented, his eyes watching Akitada’s face.

The red touches looked like blood, were meant to be blood. Yori had got the idea from the just-killed bird and applied a thick layer of red grease paint from his mother’s cosmetics to the bird and to the face of the cat. Pleased with the effect, he had then given all the other cats red muzzles. He pointed, quite unnecessarily. “Blood! Cats eat birds and mice and they get blood on them.”

Tamako came to take a look and clasped her hand to her mouth.

Noami chuckled, a dry coughlike sound. “A boy after my own heart,” he said, and put a hand on Yori’s shoulder. “So young and already so observant. What a man you will be someday!”

Tamako jerked up the child. “It is time for his nap,” she cried, and ran from the room, Yori protesting loudly.

Akitada looked at the painter with hatred in his heart. Controlling himself with difficulty, he said coldly, “We won’t keep you any longer. And there is no need to return. I will send for you if we decide on the screen.”

Noami nodded. “I am told you saw the hell screen at the temple?”

“Yes. It is greatly admired.”

The painter cocked his head. “But not by you?”

Akitada said stiffly, “I do not hold with the Buddhist theory of hell.”

“Ah! I, on the other hand, have problems with the Western Paradise.” Noami stepped closer and fixed Akitada with his deep-set, burning eyes. “What pleasure can be so great that it matches pain? We all suffer the agonies of hell, but none has tasted the joys of paradise.” With that he turned and walked out.

When Tora felt well enough to begin his investigation two days later, he dressed in the worst clothes he could find: baggy pants, liberally stained and torn in places; a ragged cotton shirt; a quilted jacket with unmatched patches, tied about the waist with a hemp rope; and old straw sandals. He untied his long hair, rubbed it with some greasy lamp oil, and wrapped a rag around his head. Finally, putting a scowl on his unshaven face, he left.

He was headed for the western city, where poor people, criminals, and outcasts lived in tenements, abandoned ruins, or squatters’ shacks in open fields. There was the heart of the underworld of the city, the refuge of gangs and notorious criminals, of vagrants, beggars, cripples, and the insane.

The day was overcast and cold. Tora walked at a comfortable pace to avoid undue strain to his recent injuries and thought about Yukiyo. She had tried her best to describe her ordeal. In a shamefaced whisper, she had spoken of her wounds, the horrible disfigurement of her face, the deep slashes across her breasts and abdomen. The monster had taken pleasure in the cutting, it seemed, but was not bent on killing her, or he would have stabbed or disemboweled her. Appalled by the viciousness of it, Tora had wondered if she encountered a demon instead of a man. His small size, his superhuman strength and cruelty, and his acrid stench all pointed to it. But Yukiyo had shaken her head stubbornly. He had been a man. As for the smell, it been more like hot lacquer or lamp oil, maybe.

Some sort of craftsman, thought Tora as he walked. It was not a useful clue. There were too many of them in the city. Tora planned to retrace Yukiyo’s steps that night, beginning with the place where she had met the slasher, at a cheap brothel. She had been soliciting there without any luck, but as she was walking away a hooded figure had reached out from an alley and drawn her into the shadows. In a hoarse whisper, the man had offered to pay her thirty coppers to go home with him. Thirty coppers was wealth; it would pay for food for weeks, and she had agreed eagerly.

They had walked a long way, through a warren of back alleys in the far western city wards. Once she had glimpsed the roof ornament of a pagoda, and not long after that they had come to a grove of bamboo and entered an empty unlit house. There, in the darkness, he had given her a cup of wine. After that she remembered nothing until she woke in another alley in horrible pain, looking up into the horrified eyes of people who found her half-naked and bleeding.

Tora found the brothel easily. It was a rickety wooden building with the impressive name Crane Terrace. A cheap wineshop occupied the street level and a few rooms above served prostitutes and their customers. The entrance was remarkable only for the stained and torn door curtain with a misshapen bird painted on it. Tora noted the narrow passage along the side of the building. Here, among the remnants of broken sake casks and vegetable peelings, the slasher had lurked that dark night, catching his victim by the simple expedient of grabbing her arm as she passed by. Tora shook his head. Even a half-starved whore should have had the good sense to run.

He ducked under the curtain into the semidarkness of the wineshop. A thick, fetid vapor of food smells and smoke almost took his breath away.

He stood on a dirt floor. On his right, a set of steep stairs led above. Straight ahead a fire pit was putting out the smoke and the indescribable smells from a large cauldron stirred by a shaggy-haired hag. On his left, a one-eyed brute sat next to a keg. Three ragged creatures eyed the newcomer blearily. The innkeeper growled, “Wine’s a copper, take it or leave it. For another copper, you can eat.”

Tora suppressed his revulsion. “Wine,” he said gruffly, joining the three guests.

“Show me the money first!”

Tora dug out a copper coin. The man snatched it from his hand, held it up to his eye, and nodded. Dropping the coin down the front of his shirt, he dipped out a measure of dark, cloudy liquid from the keg. It was easily the worst wine Tora had ever tasted and almost choked him. “I’m looking for a girl,” he said when he found his voice.

“I don’t provide whores,” snapped the host. “You get your own around here.” One of the customers snickered.

“She’s my sister,” said Tora, improvising. “Our mother’s dying and she’s asking for her, so I came to the capital to look for her. I was told she works this part of town.”

The one-eyed man said gruffly, “She must be hard up. Sorry about your troubles. What does she look like?”

This could not be answered easily, so Tora said vaguely, “About this high, kinda small bones, pretty hair. Ordinary, you know.”

“It’s not fat Mitsu,” volunteered one of the guests.

“And Kazuko’s a good lay, but bald as an egg,” added another.

The one-eyed man turned to the old hag stirring the cauldron. “What do you think, Mother?”

She wiped the sweat from her face with her sleeve. “Maybe she’s the sickly little thing. Only came a few times. Seems like her name was Yukiyo.”

Tora asked eagerly, “Any idea who she went with?”

The old woman said, “Nobody. She came in, but there were no takers. She looked so sick I gave her some soup on account and she left.”

Tora dug out another copper. “Here. We may be poor, but we pay our debts.”

This gesture worked wonders. They all fell to a serious discussion of every man or woman Yukiyo might have talked to, but the men who visited the brothel were mostly transients, nameless laborers, vendors, porters, beggars, or monks.

“Monks?” Tora asked. “Looking for women?”

His naïveté caused general hilarity. “Some of ‘em are worse than ordinary men,” cackled the old woman, “and, come to think, there was one who kept looking at the girl. Getting up his courage, I guess. But he never talked to her that I could see.”

“Is there a monastery around here?” Tora asked, thinking of the pagoda.

There was not. It was a dead end. Tora thanked them and left.

He walked northward, passing through alleys and poor streets, and began to suspect that the slasher had avoided landmarks which his victim might recall. He had zigzagged through quarters, always skirting their main gates. No wonder Yukiyo could not give a clear account of their route.

He wished he could have talked to her some more, but after his master had returned, Yukiyo had refused to visit again. Miss Plumblossom had snorted. “I don’t know what’s come over the girl. When we were leaving, she grabbed my arm and started rushing for the gate. And now she won’t come back!”

But her unexplained fright was not the only thing troubling Tora. Apparently all the slasher did was cut her. Yukiyo was certain that she had not been raped. Lust, even perverted and sadistic lust, Tora could understand, but this was something else entirely.

The quarter he was entering now was more depressing than the previous one. People lived here, if you could call it that, but there were far too many loitering men. No work meant high crime or slow starvation. And that reminded Tora of another troubling fact. The slasher had offered Yukiyo thirty coppers to go home with him. That was a lot of money for an employed laborer, let alone an outcast or mendicant monk.

He raised his eyes to scan the rooftops once again for the spire of a pagoda, when he was suddenly jostled, and a string of curses rang in his ears. Before he could blink, he was flung violently against a house wall, and punches rained on his head and chest. Tora raised his arms to protect his face and waited for his chance. But the onslaught ended as abruptly as it had begun. His assailant spat disgustedly and turned to walk off.

Hot fury washed over Tora. He raised himself from his half -prone position and rushed after his assailant. Grabbing his elbow, he spun him about, cried, “That’s for hitting a man for no reason, bastard,” and landed a fist squarely on the other’s chin. He stepped back instantly. The other man, young and poorly dressed, wore a bloody bandage over part of his face.

He raised his arm to protect himself, but Tora said, “Never mind! I wasn’t done with you for the thrashing you gave me, but I’ll put it on your account, seeing that someone else has already done the job. I don’t like an uneven fight.”

The other man growled, “Don’t let that stop you. I can beat you any day, turd.”

He was slightly taller and much wider in the shoulders than Tora, but the fight had gone out of him.

“Why did you hit me.’

Slowly the other man lowered his arm. “You pushed me, bastard. Nobody does that to me.”

“I didn’t see you. I was looking for a pagoda.”

The eye not covered by the bloody bandage narrowed, looking Tora up and down. “You’re a stranger here?”

There was no sense in inventing new lies. Tora told the story of his dying mother and lost sister again, adding some heartrending detail which brought tears to his own eyes.

The ruffian rubbed his bristly chin, reddened from Tora’s fist. “Sorry, buddy,” he said hoarsely. “Looks like you’re worse off than me. Didn’t mean to lay into you, but I’ve had a bad day with some rough fellows. My head’s sore as hell itself and when you bumped into me I was seeing stars.”

“Oh, in that case,” said Tora, “allow me to make up for it with a cup of wine. My name’s Tora, by the way.”

“Junshi.” The other man grinned, revealing a large recent gap in his front teeth. “Thanks. I won’t say no. There’s a place around the corner sells some decent muck.”

The place was worse than the Crane Terrace, being smaller, dirtier, and smellier, but the wine was slightly better.

“Now, about your sister,” said Junshi awkwardly. “She may be dead, you know. I work for the warden and I can tell you, street girls have a hard life in this quarter.”

“I know, but I’ve got to keep looking till I know one way or another.”

Junshi sighed. “Most men here can’t pay more than a copper or two for a woman, and there’s a lot of rough stuff. My boss could tell you how many dead girls they fish out of the canals or find among the garbage in the alleys.”

“By heaven! The warden!” Tora slapped his forehead with his hand. “Why didn’t I think of that? Where’s his office?”

Junshi snorted. “A warden with an office? In this quarter? If there ever was one, it’s long gone. The position is what you might call ‘by popular acclaim.’ My boss runs things here and he’s usually somewhere around the temple in the daytime.”

Tora sat up. “What temple? Does it have a pagoda? And monks?”

Junshi laughed. “They call it the Temple of Boundless Mercy—which is a laugh, seeing that mercy’s the last thing you expect to find there—but yes, it’s got a pagoda. The monks left long ago. There’s only the one hall and the pagoda left. People think demons roam about at night there. That makes it a fine meeting place for thugs. Either way, it’s unhealthy after dark.” He touched his bandage and grimaced.

Tora shuddered. However, he merely needed to find the house where the slasher had taken Yukiyo, and it was still broad daylight. “Can you introduce me to your boss?”

Junshi guffawed. “Not today. He’ll send me back after the bastards tonight. I’ll show you the way to the temple, but you’ll have to find him yourself. And don’t mention you’ve seen me.”

Tora paid for their wine, and they walked northwestward through slums and open fields with squatters’ shacks. People glanced at them and crossed the street. Junshi filled Tora in on the dangers of the quarter. “Bodies in the street almost every day,” he said in a matter-of-fact tone. “If it wasn’t for the boss, it’d be worse. The police don’t come here. They don’t like to deal with outcasts. The boss doesn’t care what a man is or has, so long as he doesn’t hurt people.”

“He sounds good to me,” said Tora. “Any bamboo groves near the temple?”

“No groves. The fox shrine has some pines around it.” They emerged into the square in front of the ruined temple. Junshi stiffened and grabbed Tora’s arm, saying, “There’s the boss now. Good luck!” and was gone before Tora could thank him.

A bearded giant stood in front of the remnants of the temple gate, his arms folded across a barrel-like chest. A group of young boys surrounded him. Tora crossed the square slowly. The semilegal standing of this individual did nothing to reassure him. He looked more like a robber chief than a representative of the law in his sector.

The giant was laughing with the boys, but his eyes found Tora immediately and sharpened. He detached himself from the youngsters and strolled up. “Good day to you,” he said. His voice rumbled from the depth of his chest like a rock slide.

Tora returned the greeting with a grin. “I am told you’re the warden,” he said. “Could you tell me where I might find a bamboo grove around here?”

The warden’s eyes narrowed suspiciously. “What’s your purpose for asking?” he demanded.

Tora bristled. “Look, I’m a stranger here, asking for directions. What’s with the third degree?”

“I like to know what strangers are up to in my district,” snapped the big man. “You either tell me what you want here, or you leave.”

Tora considered his options and said in an ingratiating tone, “Well, it’s a bit embarrassing. But here goes. I’m looking for my sister, who’s disappeared. She’s been working as a whore. Now our mother’s on her deathbed and wants to see her. Someone told me she worked around here and might have gone off with a monk. To a bamboo grove.”

The eyes narrowed even further, moving speculatively from Tora’s trim mustache to his hands. “Who told you that?”

“Er, the landlord of a tavern.”

The boss sneered and opened his mouth, but was suddenly distracted by the sounds of a fight inside the temple grounds. He snapped, “No monks in my district and no bamboo groves, either. You’d better go look in another part of town.” He strode off to investigate.

Tora wondered for a moment about the man’s reaction. Everyone else had swallowed the tale of the dying mother. He looked down at himself. His clothes looked no worse than the warden’s rags. Maybe the guy had a hangover or a toothache.

Shaking his head, he also went into the temple grounds, where a pitiful sort of market seemed to be in progress. The fight had attracted scant attention. Human scarecrows sat about on the muddy ground with items spread out for sale which looked like the garbage tossed out by the servants of the better houses, and probably was. Tora strolled about and tried to strike up conversations, but after a glance at him people turned uncommunicative. He was an outsider and his rags made him unwelcome here, for clearly he had no money for purchases, but might be there to steal from them.

It was already long past midday, and so far Tora was no closer to his objective than before. Glancing up at the old pagoda, he got an idea. If he climbed up there, he could look over the rooftops for miles. A bamboo grove within a few blocks of the pagoda should be easy to find.

Luck was with him—the entrance to the tower had not been boarded up. Inside, however, his heart fell. The steep stairs were missing steps, and a pile of rotten timbers had fallen from the upper floors. Tora peered up. The floor above him was missing so many planks that he could see through it to the one beyond. But he decided to risk it. At least there was enough daylight so he could see where he was putting his feet.

The climb was tedious because each step and each board must be tested before he dared put weight on it, and when he reached the top floor, he was sweating in spite of the cold. Slowly he made his way around all four sides, looking out over the quarter. There were only a few spots of green among the wintry huddle of dull brown roofs. All but one of these were the dark green of pines, but one was paler, the jade green color of bamboo. It was smaller than a grove or woods, but larger than the yards of houses thereabouts, and it lay only two blocks to the southeast of the temple.

Elated, Tora started downward, but in his hurry he took a misstep, lost his footing, and, twisting wildly, plunged through space.

When he regained consciousness, he was in darkness but knew immediately where he was. His back rested across a beam, his hips and legs, slightly higher than the rest of his body, were supported by more solid flooring, but his head hung over empty space. He was conscious of pain everywhere, but the worst of it in his head. After cautiously checking to see if he could move his limbs without falling again, he shifted just enough on his beam to support his head. After resting for a few moments, he tried to sit up, but a wave of dizziness hit him and he grasped desperately around him to keep from tipping over the edge. After a moment the nausea passed and his eyes adjusted to the darkness. He could make out vague shapes of flooring and part of the stairs. Carefully, inch by inch, he moved toward them, testing each plank before heaving his bruised and aching body onto it.

After a short rest, he felt his head and found his hair wet with blood and a large, painful swelling behind his right ear. Otherwise he seemed whole, though very sore in places. He looked up. If memory served, he had fallen from the fourth level to the second. The beam had caught his shoulders and kept him from landing headfirst on the stone floor of the entrance level. He must have been unconscious for hours if it was nighttime. He listened. All was silent outside the pagoda. The market was over, and people had left without discovering his fall. Or, more likely, they had ignored it.

He got to his hands and knees and crept backward down the stairs. In the almost complete darkness he had to trust his sense of touch not to step through a hole and fall the rest of the way. When he finally reached solid ground and stood up, the world spun dizzily for a moment. He staggered toward the lighter rectangle of the doorway and looked out.

The night was moonless, and the courtyard lay deserted. In the darkness, the shapes of trees, buildings, and walls loomed strangely, and he suddenly remembered the reputation of the temple. Sweat broke out on his body and his hair bristled unpleasantly. Everybody knew deserted temples were dwelling places for demons and hungry ghosts. With a shudder he shrank back into the doorway. But a strange rasping sound, followed by a skittering noise, came from under the stairs, and with a mighty leap Tora plunged down the stone steps and into the open.