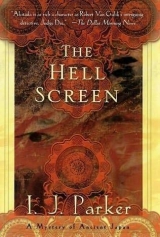

Текст книги "The Hell Screen"

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

The rest was drowned out by the gush of icy water from the other pail. It hit Akitada squarely across head and shoulders and soaked his whole body.

Without another word, Noami left.

The cold was unbelievable and produced a totally new kind of pain, perversely almost akin to burning. Not in all those years in the snow country had Akitada felt such deadly cold. He tried to think back to the stories of people who had barely escaped freezing to death. They had become sleepy and felt nothing after a while. So Noami would be disappointed after all. Akitada thought that he was beginning to lose sensation in most parts of his body already. Then the memory of amputated limbs came to him. Those who had not died in the frozen north had lost hands and feet, ears and noses to the cold. Ice was as effective as a sharp knife.

Movement and physical exertion had warmed him earlier, and he tried to move again, to pull against the rope, but his muscles were stiffening, cramping, refusing his commands. For the first time he considered seriously the fact that he was about to die. To die slowly, forgotten in this overgrown bamboo grove, while a demented artist sketched his final moments. To die without a single act of courage or affirmation. The thought of being mocked in death, and again mocked after death by the thousands who would pass by Noami’s masterpiece, revolted his very soul.

He began his struggle again, straining, his teeth grinding against the rags in his mouth, his own groans filling his ears till they drowned out the rustling of the bamboo and the distant sound of temple bells marking the hours. He gained enough purchase that his arms and shoulders could move a little and he celebrated that moment with a brief period of rest during which he attempted to move his fingers and wrists. Without them he could not work the knot loose. But his exertions were in vain. He had no idea if his fingers were capable of movement, and his wrists hurt too badly. But the physical effort had counteracted the freezing water against his skin, and one of the rags had actually come loose and fallen.

He considered his situation. Once or twice during some of his more violent efforts of pulling against the rope, he had brushed the bark of the tree trunk behind him. Perhaps he could get close enough to rub the rope against it.

Belatedly he remembered the bucket he stood in. He had lost contact with his feet when he stopped feeling them. With a convulsive kick forward, and a resulting new tear to his shoulder muscles, he overturned the bucket. He barely felt the ground under his feet, but the bucket touched his ankle. If he could get his feet on top …

It took another vicious pull on his arms and shoulders to raise his legs. He missed, sliding off the wooden surface of the bucket with the soles of his feet. Clamping his teeth into the gag, he tried again, clung precariously for a moment; then somehow the bucket must have rolled slightly and settled into the mud under him. He stood on it, supported totally by his feet, but swaying weakly, perilously, on its curved surface.

The resulting slack had brought his tied wrists close enough to see that the rope was knotted too tightly to undo, even if he could have moved his hands, which no longer resembled human hands at all. He blocked the thought of losing both hands from his mind.

Instead he concentrated on severing the rope some other way. If the trunk of the tree was immediately behind him, he could lean backward against it. If not, he would tumble off the bucket again. He tried not to think of the pain which would follow, and reached back. And touched the tree. He leaned back cautiously, feeling the sharp bark against his back, letting it support some of his weight. But there was very little slack in the rope now and pushing his bound wrists up and down against the bark of the tree required him to stretch upward from his shoulders and against the pull of the rope. Each movement sent new arrows of pain through his shoulders and caused him to teeter on the bucket beneath his feet.

He persisted. The bucket settled more deeply into the mud, and at some point of the continuous push and pull he dislodged the cloth covering his face and sucked in a deep breath of clean air and gazed at the stars. The relief brought tears he could not stop.

The rubbing motion became automatic, the pain a fact of existence, proof he was alive. He was hardly conscious of the moment when the sharp bark of the tree bit into his skin.

And then the rope parted and he fell.

He fell hard, totally unprepared for freedom, and lay there for a time, too stunned to form any plan for further action. Above him rose the massive trunk of the tree, splitting into black branches and twigs against the midnight blue, star-spangled sky.

After a while, he rolled on his side and brought his arms down, cradling them against his chest. Lowering his arms in itself was exquisitely painful, and even after that agony dulled, there was more pain, though the worst spasms were different from the earlier ones. He rested some more and tried to move his fingers again. Evidently the rope, once severed, had parted completely, because his wrists, black with blood, were free. He tried to warm his hands against his belly and could feel them moving. Thank heaven.

He next thought of getting rid of the gag. He tried raising his hands to his face, but was unable to make his fingers take hold of the fabric and instead rubbed the side and back of his head against the ground. A protruding tree root shifted the cloth strip enough that he could force the gag from his mouth with his tongue.

He vomited, but felt better afterward, and struggled into a sitting position. The strip which had held the gag in place still encircled his head, covering one of his eyes. He pushed it up and off and looked around. The tree stood in the middle of dense bamboo. The sky above had paled and the stars were becoming faint. Almost dawn. How much time had passed? Noami had said he would return in an hour. Akitada could call for help now, but that might simply bring his tormentor back, and how was he to deal with him in his present condition? His ankles were still hobbled together; he could not untie the knot, because his hands were useless. Besides, his knees shook so badly when he tried to stand that he fell down again.

He must crawl, hide somewhere in the garden, give himself time to recover more strength, perhaps untie his legs.

He crawled, slithered, rolled, more like a snake or worm than a two– or four-legged creature, deeper and deeper into the bamboo thicket, until he reached the boundary wall and could go no farther. Here he sat up, leaning his back against the wall, and rested.

All was still blessedly silent. After a while he began to work on his hands again. The icy skin felt like something alien against his chest and cheek, and he put his fingers in his mouth to warm them. Then, taking them out, he watched his fingers move in the dim light, one by one, reluctantly and eerily, since he could not feel the movement. One finger at a time, they all moved, pale white like the underbelly of a dead fish against the dark, oozing flesh of his wrists. He exercised them again and again, warming them briefly in his mouth in between.

Finally came the moment when he felt a faint itching in one of his thumbs. It spread and changed to an unpleasant tingling, but he was so encouraged that he increased his hand exercises, adding slow stretches of his arms and shoulders.

He was just starting to explore the rope around his ankles when he heard a distant shout.

Noami! He had found his prisoner gone.

Akitada sagged hopelessly as the sounds of thrashing and breaking bamboo began. Too soon. He could not get up yet. Not even walk a few steps, let alone run. The sounds of frantic searching, loud in the still predawn air, were coming closer. He had left a trail for Noami to follow.

Pointless though it seemed, Akitada bent to work the knot, his half-raw fingers protesting until blood trickled from under his fingernails. The knot was wet, partially frozen, and sharp bits of ice were cutting his skin. It was no use. Looking around, he saw a chunk of stone the size of an infant’s head. Scooting over, he tried to pick it up. But his fingers would not grasp, nor would his arm muscles support, even such a slight weight in their present condition. He staggered to his feet, bent, and scooped it up by placing both his hands underneath and lifting with his back. Then, cradling the stone against his bare belly, he shuffled the few feet back to the wall and propped himself upright against it to wait for Noami.

TWENTY-ONE

The Mended Flute

When Tora regained consciousness, he thought at first that he had fallen the rest of the way down the ruined pagoda. But the rustling of leaves eventually penetrated the thick fog of pain in his head, and he rolled onto his back to stare up at the night sky. Fronds of bamboo dipped over a garden wall and soughed dryly at the slightest breath of air. He sat up and immediately reached for his head. The stars above were dancing wildly, and the wall undulated like a snake. He had to blink hard several times before the world settled down to its usual solidity.

At that point memory returned. The bamboo grove. The slasher. And someone had jumped him from behind. He felt for the string of coppers in his sash and found it. At least the bastard had not got the rest of his money. That amounted to a miracle. Then Tora recalled the short hooded figure who had twisted from his grip at the gate.

He felt his head again. The crusty lump he had sustained in his earlier fall had spawned a twin. The whole back of his skull was swollen and tender. A short man had struck this blow, and that convinced him that his attacker had been the hooded fellow—the slasher himself ?

It seemed wise to move in case he returned to finish the job.

Tora staggered to his feet, waited a moment for his stomach to settle, then groped along the wall toward the rear of the property. The place was large and the wall high and well maintained but appeared to have no other gates.

The blind backs of storage sheds, belonging to the next street and surrounded by broken fencing, weeds, and shrubbery, adjoined in the rear. Feeling dizzy, Tora sat down to think over his options.

If his attacker had been the slasher himself, it was strange that he had left him unconscious next to his hideout. Why not make sure his victim would not raise an outcry? Maybe he had gone back for his knife. Tora shuddered. On the other hand, leaving a murdered man lying about would cause some awkward questions even in this part of town.

Tora started feeling better, but the sharp night air penetrated his thick clothing. He got to his feet and became aware of a faint moving glow above the dark mass of bamboo behind the wall. Someone was walking around inside with a lantern. He listened and thought he heard a faint voice. So the bastard was not alone!

Tora continued along the wall until he reached the street again, verifying his suspicion that there was no back gate. What now? He could go home and tend to his wounds. After all, it was the middle of the night. Besides, he had probably alerted his quarry. Tomorrow, by daylight, he could return with Genba, knock on the gate, and force his way in. The little creep might be strong for his size, but he was no match for the combined skills of Tora and Genba.

It was the wisest choice, but something held Tora–a strange and perverse urge to get over the wall and into the slasher’s lair as soon as possible.

Shivering with cold and light-headedness and in spite of a monstrous headache and assorted other pains, Tora retraced his steps to the back of the property and took a closer look at the ramshackle storehouses.

He found a section of broken but sturdy fencing, just long enough to prop against the wall for a ladder. He listened. Everything was quiet, and he decided that whoever was inside had gone to bed.

Tora climbed up, straddled the wall, and looked down on the other side. A far jump, but it could not be helped. Thick stalks of bamboo grew close to the wall and he leaned out to take hold of one to break his fall and jumped. The bamboo bent and made an infernal noise, creaking and rustling as if a huge bear were rampaging about, but Tora landed quite softly. After the bamboo had snapped back with more hideous racket, he waited for a few moments, but all remained quiet.

Carefully he made his way through the grove, pausing from time to time to make sure that the rustling sounds around him were no more than the night breeze in the leaves or some small animal. In the darkness it took him a long time to get close enough to the house to see its size and layout. It was larger than he had expected and in good repair. But the garden had been allowed to grow into a tangled wilderness, the bamboo covering everything except a small area surrounding a large leafless tree some distance away.

The house was plunged in silence and darkness. Tora considered going inside, but without knowing precisely where the slasher was, this was impracticable. At a loss, Tora glanced around the garden again. A distant crackling sound attracted his attention. Whatever was moving through the bamboo sounded larger than a rat or cat. He decided to explore.

The sounds came from the direction of the tree. He followed a narrow well-trodden path through the bamboo thicket to the clearing and stopped. Pale in the murky darkness, rolls of paper lay scattered about. A large upturned basket rested among them, and a long rope dangled from a branch of the tree. There was nobody about.

Tora approached cautiously. A container of brushes and a large inkstone and water container stood near the basket. Beside the tree, a water bucket lay on its side among some rags. Whoever had worked here was messy; Tora decided. He kicked one of the papers and it unrolled.

There were drawings on it. In the gloom it was hard to see, but they seemed to be pictures of a nearly naked man tied to a tree. Tora eyed the tree and the rope. Then he picked up the picture, and another, and a third. Swallowing sudden nausea, he went to take a closer look at the rope and rags.

The rags had been wet and were beginning to stiffen in the freezing temperature. The rope, also wet, looked frayed. Some shorter pieces of rope on the ground showed dark stains. Picking up one of these, Tora raised it to his nose. Blood! He had found the slasher, and he had been torturing some other poor bastard even as Tora closed in on him. Tora wondered if the monster had dragged away a corpse to bury it. Perhaps that was when he had heard something. He glanced around the perimeter of the clearing.

He was lucky, for at that moment he caught sight of someone rushing down the path toward him. In this light, it seemed an apparition, moving silently, its face distorted like a goblin’s and a long knife in its right hand.

Shaking off a superstitious panic, Tora dropped the piece of rope and sidestepped the slashing ball of fury, tripping him as he passed. The creature was, thank heaven, real enough, and he flung himself on top of the thrashing figure. This time, he took no chances. He remembered the strength of this small, agile creature. Catching the flailing knife arm, he twisted it back so violently that the man’s shoulder dislocated with a snap. With a shrill scream, the slasher stopped moving.

Tora threw the knife deep into the bamboo, made sure his captive had fainted, and got the rope pieces to tie him up securely.

Meanwhile, the night had become less murky. His surroundings began to take shape with sharp outlines. It must be close to dawn. In the faint light, Tora saw that the rope ends he was using were frayed and torn, not cut. Whoever had been tied to that tree had managed to free himself. Breaking the heavy rope must have taken extraordinary patience and strength.

Tora rose to his feet. The clearing lay empty and silent. He called out, “Hey! It’s safe! You can come out now.”

No response. Somewhere a bird chirped sleepily. It occurred to Tora that whoever had escaped the slasher’s torture would hardly emerge from his hiding place at the invitation.

Making a methodical circuit of the clearing, he saw where dried weeds and fallen leaves had been disturbed by something large rolling or dragging through the bamboo. For a moment, Tora feared that the slasher had managed to kill his victim after all and had dragged the corpse away. But then he found the partial print of a bare foot. The monster’s victim had been too weak to walk and had crawled away, pushing and clawing forward with toes and hands. Cursing under his breath, Tora followed the track as quickly as he could, prepared at any moment to stumble over the dead or unconscious body of a mutilated person.

Preoccupied with the ground, he did not see the wall or the pale figure leaning against it. One moment his eyes were fixed on the earth, the next there was a flash of movement, and he felt a blinding pain on the back of his skull. Sagging to his knees, he plunged into darkness.

Tora was the last person Akitada had expected to see emerging from the bamboo thicket. Thinking only of Noami, he put the last shred of his remaining strength into raising and bringing down the rock at the precise moment when the leaves parted. It seemed an eternity passed, and when the moment finally came, Akitada’s arms acted independently. He could do no more than slow the violent descent of the rock at the last moment. Too weak to control the downward stroke, he watched in horror as Tora crumpled before him. Letting the stone drop from his lifeless hands, he began to shake again. He had killed his friend who had come to his rescue.

He fell to his knees beside Tora. “I’m sorry. I’m sorry,” he sobbed, hot tears stinging his cheeks as he rocked back and forth. He stroked Tora’s head and his swollen hands were covered with warm blood. With an inarticulate cry, he collapsed across Tora’s broad back.

“Sir? Sir? Is that you, sir?”

When the words penetrated the fog of weakness and misery, Akitada struggled up. “Are you alive, Tora?” he asked feebly. “I thought you were Noami, come back to finish me off.”

Tora sat up, too, holding his head. He chuckled weakly. “And I thought you were the slasher’s accomplice. That’s the third knock my head caught tonight.”

The sky above had turned a silvery gray, and birds chirped all around them.

“I’m sorry,” Akitada said again. He was still shaking, and his teeth chattered uncontrollably, but he looked at Tora with joy. “I’m so glad you came. Yori got home, then?”

“Yori?” Tora lowered his hands and stared at his master. “Holy heaven!” he exclaimed. “What did that bastard do to you?”

Akitada smiled bitterly through chattering teeth. “An experiment in artistic realism. The effect of freezing on the human body. For the hell screen,” he said with some difficulty, and struggled to his feet. “Never mind that. What about Yori?”

Tora stood up. “I don’t know about Yori. I haven’t been home since yesterday morning.”

Akitada suddenly felt faint. “Dear heaven! Then the child is still lost. Come. We must find Yori.” He grasped Tora’s shoulder for support. “Before Noami catches us.”

“If he’s an ugly little runt with spiky hair, I’ve caught him.” Tora slipped off his ragged coat and shirt. These he wrapped around his master and then put his arm about him to support him. “Your hands, sir,” he muttered. “They look terrible.” Akitada hid them inside Tora’s quilted jacket.

Together they staggered back to the clearing. Noami was conscious and moaning. He glared balefully when he saw them. “Untie me this instant!” he shrieked. “You’ve broken my shoulder. I may never be able to paint again!”

“Good!” remarked Akitada, sinking weakly on the upturned basket. “Make sure, Tora, that he cannot escape before the police get here.”

Tora glanced at the rope dangling from the tree, grinned, and jerked Noami to his feet. The painter screamed. Tora carried him to the tree, attached the rope to his bound wrists, and pulled it taut. The painter screamed again and fainted. His weight caused him to flop forward.

“I wrenched his shoulder out of the socket earlier,” Tora explained with great satisfaction. “When he comes to, he won’t try to move if he can help it.”

Akitada grimaced. “Let him down enough so his feet support his weight,” he said.

Tora obliged, but the unconscious man still drooped forward. Akitada got up from his basket. “Here, set him on this and then let’s go.” As Tora adjusted the unconscious Noami, Akitada flexed his arms and legs experimentally to get some circulation and warmth back into his muscles. But he was too weak and in too much pain and would have fallen if Tora had not caught him in his arms.

Subsequent events were a haze in Akitada’s mind. When they emerged from Noami’s gate, they encountered the giant warden and Genba. Reassured by them that Yori was home safe, Akitada felt his knees buckle under him. He was placed on a litter and whisked home.

His trials, however, were far from over. Fussed over by a white-faced Tamako, he was stripped and immersed in lukewarm water by Genba and Seimei, an experience which turned out to be excruciatingly painful to his nearly frozen flesh. Later Seimei treated his lacerated wrists by applying ointments and herbal packs, which he changed every few hours. Akitada’s hands began to swell and burn. The skin cracked in places and oozed blood.

In spite of this, the satisfaction of knowing Yori was safe was enough in itself, and after drinking a sleeping draught, Akitada asked no questions and slept.

But the exposure during the freezing night had undermined his strong constitution, and his sleep turned into a virulent fever filled with hallucinatory images from the hell screen.

He tossed between nightmare and waking for six days and nights. Finally, on the seventh day, exactly a week after his escape, he woke up clearheaded and hungry. His eyes fell on his sister. Yoshiko sat by his bedside, quietly sewing some child’s garment, no doubt Yori’s. Memory returned abruptly, and he was filled with an immense gratitude that both he and his son were alive, that he might see him grow up after all, play games with him, and laugh at his childish antics together with Tamako.

He longed for Tamako, but perhaps she had gone to rest. He had given them all too much trouble. Yoshiko looked drawn and tired, quite as pale and worn as she had been when he had first seen her on his return from the north. He lay comfortably warm in his silken bedding—how different from that hellish night in Noami’s garden—and wondered if he had done the right thing, forbidding his sister her last chance for happiness. It struck him now that he owed his own happy family to her, for it was Yoshiko who had brought him Tamako.

If only that fellow Kojiro could be cleared of the murder charge. He was innocent, and a much better—and wealthier– man than Akitada had expected. Well, he must see what he could do for him as soon as he was up and about again. He cleared his throat.

Yoshiko’s head shot up. “Akitada?” She looked at him anxiously. “You are awake?”

Silly question. Akitada meant to say yes, but managed only a croak.

“Don’t try to talk,” she cried, and put her sewing by to reach for a teapot on the brazier at her side. She poured a cup and supported his head as he drank.

He was very thirsty and emptied the cup.

“More?”

He nodded and she gave him another cup.

“Thank you,” he managed to say after that. “Where is Tamako?”

“Playing with Yori in his room. Shall I fetch them?”

He felt a little hurt that Tamako had left him, but shook his head. “Later.”

“How are you feeling, Elder Brother?”

He managed a lopsided grin. “Hungry. How’s Tora’s head?”

She got up. “Fine. You know Tora. He recovers quickly. He and Genba have been spending most of their time with Miss Plumblossom and the young actress. If you think you will be all right by yourself for a few minutes, I will go heat some rice gruel in the kitchen.”

Akitada nodded and she left. Just as well, for he did not relish the idea of having her company for a trip to the privy. Testing his limbs, he found them pain-free but strangely languid. He pushed the covers back and saw the white silk bandages about his wrists. His hands were no longer swollen, but stiff and covered with scabs. Getting to his feet was easier than he thought, but he had to catch hold of a screen when he took his first step. Fortunately, his head cleared and he negotiated the hallway and gallery to the privy without incident.

Feeling better when he emerged, he decided to find his wife and son.

They were, as Yoshiko had said, in the boy’s room, kneeling over some papers and busy with brush and ink.

This brought back memories of Noami’s lessons and momentarily nauseated him. He grabbed hold of the open doorway. Tamako looked up.

“Akitada!” She was on her feet and, flinging her silk skirts aside, rushed to him to put her arms around his waist.

“A fine greeting for your husband, madam,” he teased. “Have you been taking lessons in the Willow Quarter?”

She immediately dropped her arms and flushed scarlet. Bowing primly, she said, “Forgive my immodesty, please. I thought you were going to fall and… and …”

Akitada reached out and pulled her into his arms, burying his face in her soft, sweet-smelling hair. “You may take me into your arms anytime, my wife,” he murmured.

“I have missed you,” she whispered.

Feeling her pliant body press against his, he took a ragged breath and reached for her sash.

Yoshiko appeared in the corridor, carrying a small footed tray with a steaming bowl on it. “Oh,” she cried, “so here you are. You should not have tried to get up so soon after having been in a fever for a whole week.”

Akitada released his wife reluctantly. “A week?” he asked, flabbergasted.

The women nodded and half pushed, half drew him into the room to sit on a pillow. Wrapping him into Yori’s quilts, they made him eat his gruel. He smiled at Yori between sips, wondering why the boy was so quiet. He tried to talk to him, to ask questions about what had happened, but the women would not permit it until he had emptied the bowl.

The boy sat wide-eyed, watching his father finish. Then he held up a sheet of paper. It bore the wobbly and smudged character for “A Thousand Years.”

A New Year’s wish. Of course, it was almost that time. Akitada nodded and smiled. “A remarkably fine sign, and very appropriate.”

“Do you really like it, Father?” Yori whispered, perhaps out of respect for his father’s condition. “It’s Chinese for having a long life and good fortune in the coming year. Mother showed me how to write it.”

Tamako read and wrote Chinese because her father, a professor at the Imperial University, had taught her as if she had been a son.

Putting the empty bowl aside, Akitada asked, “Do you remember the night at the painter’s house?”

Yori nodded. “You sent me home, but I got lost. I asked a man to show me the way. I said, ‘Take me to the Sugawara mansion!’ He was quite rude and laughed at me, so I stomped on his foot and told him I would have him beaten if he did not obey instantly. He grabbed me by the arm and shook me, saying he would wring my neck like a chicken, but a huge giant appeared and snatched me away. The giant was bigger than Genba, but very dirty. He took me to his hut and gave me soup. He did not laugh when I told him to take me home, but he was not terribly polite and he did not obey me. I went to sleep then.”

“You were very brave!” Akitada complimented him.

Yori nodded. “I was.”

So the warden had saved the boy. Good man! He would have to do something for him. If only Yori had told the warden where Akitada was. He could have been rescued before Noami strung him up in the garden. But that was ungrateful. He looked at the women. “How did you find out what happened?”

Tamako said, “The warden brought Yori home. When we asked about you, he remembered that Yori had said something about his father. We woke up the child and he told us about the painter’s house. After that it was easy. The warden and Genba went to find you. They got there just as Tora carried you out in his arms.”

Akitada corrected her. “I was walking. But I must thank the warden in person for returning Yori. He appears to be a very decent fellow and an excellent influence in a bad section of the capital. Besides, I have some questions about Noami’s activities. By the way, what happened to the man?”

The two women looked at each other. Tamako said diffidently, “Superintendent Kobe called daily to inquire about your condition. He mentioned that the painter hanged himself.”

“What? In prison? They must have been unusually careless.”

Tamako avoided his eyes. “Not in prison. They found him hanged in his garden.”

Akitada stared at her. “In his garden? But we left him alive.”

“Oh. The superintendent thought it strange. He wants to ask you about it.”

How was this possible? Akitada thought back to his last sight of Noami. Tora had fastened Noami’s wrists to the rope from the tree branch and then shoved the basket under him to prop him up. How could Noami have hanged himself? Even if he had gained consciousness and, like Akitada, climbed on the basket, he could not have tied the rope around his neck with that dislocated shoulder. He shook his head in bafflement.

When Kobe came to see him, Akitada had had a bath and been shaved by Seimei. He had spoken with Genba, Tora, and the recovered Harada, had eaten a light meal of fish soup, and was resting comfortably in his study.

The superintendent approached warily, his face anxious. Akitada greeted him affably. “Good afternoon, my friend. I am grateful for your concern during my illness.”

“Oh,” said Kobe, sitting down with a sigh of relief, “you do look much better now. Yesterday I was afraid you would not make it.”

Akitada chuckled and poured two cups of wine. “My wife says that Noami hanged himself?”

Kobe gave Akitada a sharp look. “It is true that we found him hanging by the neck from a rope tied to a tree branch.” He paused, then added, “His hands and feet were tied, and one of his shoulders was dislocated.”