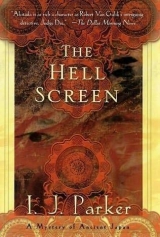

Текст книги "The Hell Screen"

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

FOURTEEN

A Taste of Ashes

When Akitada entered his study, the short, rotund figure of his brother-in-law was sitting on a cushion by his desk cheerfully sipping wine. As soon as Toshikage saw Akitada, he arranged his face into suitable gravity.

“Good afternoon, Brother!” he said with a bow. “I hope you don’t mind my waiting in your room. Seimei brought me some warm wine. Please have some. It takes the chill off the weather. You look frozen.”

“Good afternoon, Toshikage.” Akitada touched his face and ears. They were icy. Preoccupied with his family troubles, he had forgotten to turn up his collar against the wind. He untied his hat and went to warm his hands over the glowing brazier, then held them over his ears. The cold had given him a headache. “You are always welcome here, Brother,” he said to Toshikage, who filled a second cup with wine.

Akitada had become fond of his brother-in-law, but his presence here today struck him as ominous, because of Yoshiko’s threat of leaving. Apparently she had been serious. The situation left him utterly helpless. His solemn resolve to take care of his family had already ended in the first failure.

Toshikage extended the wine cup. Akitada attempted a smile and drank. Toshikage was right. The wine, sweet and mellow to the tongue, lit a fire in his belly. He felt marginally better. All day he had been as tightly strung as a bow, afraid that his self-control would shatter. He rubbed his temples, waiting for the headache to recede.

Toshikage, searching Akitada’s face, said, “We both came the moment we received Tamako’s message. What does the superintendent say?”

“Oh! You brought Akiko?” Then the full implications of Toshikage’s words struck Akitada momentarily speechless. Tamako had sent for them! She had taken Yoshiko’s side and sent for Toshikage and Akiko the moment his back had been turned. No doubt the three women were together even now, packing Yoshiko’s clothes and making plans for her life in Toshikage’s household. He felt slightly sick. Between them the women had cast him in the role of the ogre.

Toshikage’s face wrinkled with new concern when he saw Akitada’s expression. “What is it? Bad news? Will she be arrested after all? It is outrageous! We must stop him. I tell you what: I’ll go to Kudara. He’s a major counselor, a member of the Great Council of State. Kudara’s the sort of man who insists on class privilege. He’ll tell this Kobe fellow a few things and we’ll have Yoshiko back home in no time.”

Toshikage’s offer was kind, but Akitada’s way, no matter how mortifying, was preferable. He had no desire to put himself into debt to one of the great men. Such favors came with a price, and the price was too often one’s integrity. He hurriedly reassured Toshikage, “No, no. The case is not as desperate as all that. I have managed to stave off the worst by throwing myself on Kobe’s mercy.” The memory of that difficult step was still painful, and he grimaced. Toshikage raised his brows questioningly, and Akitada confessed, “I doubt he was motivated by mercy. The situation was fairly humiliating.”

Toshikage bristled. “That man gives himself too many airs!”

“We don’t get along too well because he thinks I meddle in his affairs. On this occasion he thought I had finally overstepped the bounds of legality by smuggling messages and instructions to a prisoner about to come to trial. Has Tamako told you Yoshiko’s story?”

Toshikage looked uncomfortable. “Yes, er, that is, I understand that this Kojiro is a former suitor and she went to visit him in prison.”

“Yes. Repeatedly. And it is worse than that, I’m afraid. She appears to be besotted with the man. He is totally unsuitable, but she insists on marrying him as soon as he is cleared of the murder charge. I have forbidden it, of course.”

“Ah, hmm.” Toshikage nodded, avoiding Akitada’s eyes and fidgeting.

Akitada was not encouraged by Toshikage’s manner to hope that he was on his side, but he decided to get it over with. “She has defied me and informed me that she will leave this house. I assume you are here to take her back with you?”

Startled, his brother-in-law looked up. “Heavens, no. I came to offer my support against those high-handed police authorities. I had no idea things were as bad as that. She is leaving? Oh, dear, I have no wish to come between you two.” He paused to digest this new information. “By the Blessed Buddha,” he said, shaking his head, “if it’s not one thing, then it’s another. I’ve only just settled my own problems, when here is this new thing cropping up. But my dear Akitada, you are the head of her family. She must obey you. What do you want me to do? I am completely at your service.”

“Thank you.” Akitada did feel profoundly grateful. It meant a great deal that Toshikage at least recognized his authority and would support him against the women. “I want Yoshiko to stay here,” he said, “but I will not force her beyond reasoning with her. If worse comes to worst, I would be very grateful if you offered her the shelter of your home.”

“But of course. She is Akiko’s sister and I am very fond of her.”

“How is Akiko?”

Toshikage beamed. “Blooming! In view of your trouble, I am almost ashamed to admit that my own home has never been happier. And just think, that little problem of the missing treasures has been straightened out. Stupid of me to trouble you. All the lost items have turned up. It was just a silly mistake. I am so glad that you did not have to become involved.”

So Toshikage’s son had managed to return everything without arousing his father’s suspicion. Akitada feigned ignorance. “Really? Where did you find them?”

“Oh, that careless son of mine forgot that we had sent a large number of things to be cleaned and repacked in new boxes along with other items. Takenori should have checked them off the master list. The fellow who does that sort of thing for us delivered most of the things last month, but he brought these back only yesterday. Everything is there, thank the heavens. Of course, in theory I am responsible for knowing where things are, but Takenori went before the director, threw himself full-length on the floor, and confessed his oversight. The director was very understanding. Silly boy! Of course, he should have been more careful, but I was quite impressed with his behavior. And let’s face it, I have been laying too many of my own duties on his shoulders lately.” Toshikage’s face brightened. “And there is even better news. I have thought of a plan to bring his brother Tadamine home for good. There will be several openings in the Imperial Guard come New Year’s Day. If he wants to play soldier, let him do it here in safety. What do you think of the idea?”

Biting his lip to keep from smiling, Akitada said he thought it the perfect solution. Privately he suspected that young Takenori had considerable hidden talents for a political career. Apparently he had had no trouble convincing Toshikage that the cleaning of the treasures and the reassignment of his brother had been his father’s idea all along.

Toshikage rubbed his hands gleefully. “Yes, isn’t it wonderful? I shall soon have both my boys back with me, and another one on the way.” He positively glowed with happiness.

Suppressing a sigh, Akitada congratulated him on his good fortune and poured more wine to toast the happy news.

Toshikage recalled the reason for his visit. His face fell. “Forgive me, Brother. I should not have forgotten Yoshiko’s problem so quickly. What did Kobe say?”

Akitada grimaced. “He commiserated with me on having a sister who could shame her family to the degree of claiming to be the wife of a peasant jailed for raping and murdering his own sister-in-law.”

Toshikage sucked in his breath. “Surely she did not do that!”

“She did. It was the only way she could gain access to him. They allow wives to bring food to the prisoners.”

“Oh, dear! Oh, dear! How angry you must have been! Did you beat her?”

Akitada was taken aback. The thought of striking his sister, or any woman, had never entered his mind and he felt slightly-sick at the notion. “Of course not,” he said. “Besides, she is a grown woman.”

Toshikage shook his head and waved a monitory finger. “All women are children. And the provocation, my dear Akitada. I admire your restraint. I would have beaten my son if he had embarrassed me half as much.”

“But not a daughter or sister.” Or your wife, Akitada hoped, thinking of the troublesome Akiko.

Toshikage, guessing his thoughts, grinned. “Well, perhaps not quite so hard. Women cannot be held to the same standards as men.” He sighed. “It’s a fine mess. What will you do?”

“Of course Yoshiko will not be permitted any further contact with the prisoner. But Kobe has agreed to let me investigate the case with certain conditions. I am to work under his command.”

“Oh, dear! Oh, dear!” Toshikage muttered again, shaking his head. “With your rank! How very embarrassing for you.”

Akitada felt himself flush. “I had no choice. Kobe and that man have my sister’s reputation in their hands. One word from either of them, and she is ruined. In fact, unless I can clear Kojiro of the murder charge, she may never be able to hold up her head in polite society again.”

“Amida!” said Toshikage, and fell silent, momentarily bereft of words. They sat and considered the situation. Gossip ran like a firestorm among the “good people,” and a scandal involving his wife’s sister would touch Toshikage’s family also. To Akitada’s surprise, Toshikage was not thinking of himself. “Poor girl!” he muttered. “We must do our best to protect her. What sort of man is this Kojiro? Does he strike you as capable of the crime? Is he likely to use Yoshiko to protect himself?”

“I am positive that he is not capable of either.” Toshikage had put his finger on something which had been troubling Akitada ever since his meeting with the prisoner. “I don’t know why I am so certain. The man puzzles me. He appears surprisingly well educated. Quite gentlemanly, as a matter of fact. And he behaved well about Yoshiko. He tried to cover for her. Of course, Kobe did not believe him. In fact, I was very favorably impressed until he thought I had come to help him because Yoshiko asked me to. At that point, I am afraid, I got very angry at his brazen assumption that I might countenance such a relationship. Since Kobe stood there watching to see how I would take it, I disabused them both quickly of such an idea. Kojiro became quite stiff after that.”

“But you will attempt to clear him?”

Akitada nodded. “He denies having had an affair with his sister-in-law, and I believe him. I also think he is sincere about his feelings for Yoshiko. His brother told me that Kojiro started drinking because of an unhappy love affair. I think the occasion was the rejection of his suit for Yoshiko.”

Toshikage’s eyes grew a little misty. “Heavens! Knowing your honorable mother’s firmness of purpose, that must have been painful in the extreme. A truly romantic tale. Too bad you don’t like the fellow.”

Akitada raised his brows. “My dear Toshikage,” he said brusquely, “it has nothing whatsoever to do with my liking or disliking the man. He is a commoner.”

“Ah. Yes. That is very true. I forgot.”

Akitada gave his brother-in-law an irritated look. “To get back to the murder: Kojiro’s story suggests that he may have been drugged. On my visit to the temple, I observed that the young monks bring only water to the guests, but Kojiro says he was given tea. Being thirsty, he drank it and immediately fell asleep. When he was woken by the monks, he was in his sister-in-law’s room. To this day he has no idea how he got there. He says his head felt fuzzy and someone had poured a pitcher of wine over him so that everybody assumed he was drunk. He thought so, too, at first, remembering the blackouts he used to suffer when he was still drinking. Wine affects him worse than most men. But he swears he stopped drinking, and I tend to believe him. Anyway, it explains why he confessed to the crime in the beginning but later changed his mind. I think there was something in the tea. The bitter taste would hide whatever sleeping powder someone gave him.”

“Of course! How clever of you to figure that out.” Toshikage paused. “But wasn’t the door locked from the inside?”

“Slamming those doors will make them lock of their own accord. Guests are asked to leave the doors open when they depart, but the monks have a key in case someone forgets.”

“The monks have a key? But that means one of the monks could be the murderer.”

“Yes.” Akitada was surprised at his brother-in-law’s sharpness. He had not expected it from Toshikage, who had been totally helpless about his own problems. “Quite right. A monk, or someone else who knew where the key was kept. I cannot help thinking that there is more involved here than mere lust. Someone wanted her dead.”

“Her husband?”

“Perhaps.” Akitada decided to share his thoughts more often with his brother-in-law. It was helpful to have someone to listen to and comment on his theories. “Nagaoka was away from home the night of the murder. And Kobe is receptive of the idea.”

His brother-in-law smiled. “There you are, then.”

“Yoshiko won’t be much better off having her name linked with a killer’s brother. Kojiro, by the way, threatened to confess again, if we accuse Nagaoka. His affection for his brother is quite strong.” Akitada grimaced. “I have some difficulty accepting that Nagaoka could treat his own brother so cruelly.”

“My dear Akitada, our history is full of instances of fratricide.”

Seimei came in with another flask of hot wine. Clearing his throat apologetically, he said, “The ladies have asked me to tell you that they are anxious to hear what happened at the prison.”

Akitada rose. “Yes, of course. I forgot. I suppose we had better go now.” He sighed. His head still ached and he dreaded the coming interview.

Seimei followed them, carrying the wine and their cups.

At first glance the gathering of the three young women looked charming and normal. Dressed in pretty silk robes, dark because of the mourning period, but most becoming, their long, lustrous hair spread out behind them, they sat or reclined on cushions placed around a large brazier.

But the faces they turned to the men were not cheerful. Akiko looked angry, and Yoshiko was sickly pale, with bluish circles under her red-rimmed eyes and a general air of frailty.

Akitada’s eyes passed quickly from them to Tamako. His wife was sitting stiffly upright, her normally placid face tense and stern. His heart misgave him. Feeling guilty that he had delayed so long with Toshikage, he stumbled into apology. “Forgive me, but we were discussing the case against Nagaoka’s brother.” As soon as he had spoken, he felt that this excuse simply made the matter worse. Lately he always seemed to be saying the wrong thing to Tamako. Their easy, companionable relationship had changed to one of disapproval and hurt feelings. He went on hurriedly, “The news is good for Yoshiko at least. Kobe has agreed to leave her in peace for the time being.”

Tamako said quietly, “Thank heavens for that!”

Akiko was less pleased. She cried angrily, “I should hope so! Who does the man think he is?”

Only Yoshiko did not speak. She looked down at her hands, plucking at the fabric of her robe.

Akitada was aware of new irritation with his youngest sister. She clearly had no idea what danger she had been in and what it had cost him to protect her. What had she expected? That he would get her lover released and bring him home to meet the family? He suppressed an urge to shout at her and instead seated himself next to Tamako. His wife immediately rose, offering her cushion to Toshikage, who accepted.

Seimei filled their cups with wine. When he was done, he hesitated and looked at Akitada. But his master’s eyes were following Tamako, troubled that she had withdrawn from him, trying to catch her eye. Being ignored, the old man withdrew on soft feet.

“Well?” Akiko demanded impatiently. “What happened? Don’t keep us in suspense, Akitada!”

“What? Oh. I told Kobe your sister’s story. Under the circumstances, only the truth would do. He expressed shock and sympathy. Since he did not question it, the rest was easy enough. I asked to be allowed to investigate the crime in order to clear Kojiro. He agreed, provided I work under him.” No point in going into the unpleasant details of the interview.

Tamako looked at him now and he knew that she understood his humiliation. He tried a reassuring smile, but she only bit her lip, glancing away again. His sisters received the information differently. Yoshiko’s face lit up with hope, and Akiko clapped her hands. “Wonderful!” she cried. “That should take care of the problem neatly. You will prove the fellow innocent, and everyone will forget Yoshiko was ever involved in the matter.”

“Thank you for your faith in me,” Akitada said dryly. “At the moment I am not nearly as sanguine as you are.” He glanced at Yoshiko. She had paled again, and her fingers resumed plucking and pleating her gown. “Well, Yoshiko?” he asked, hoping his voice was not as harsh as it seemed to him. “What have you decided to do?”

Without looking up, she said softly, “I shall wait.”

“For what?” Akiko demanded. “Put the fellow from your mind and go on with your life. If it were not for this stupid mourning period, Toshikage and I would soon have you in the right company to meet gentlemen.”

Though Akiko expressed Akitada’s views precisely, her tactlessness irritated him. He asked again, “Yoshiko?”

She raised tear-dulled eyes to his.

“Will you remain here, in your home, for the time being?”

“Of course she will,” Akiko cut in. “All this nonsense about leaving because she brought dishonor to you! How would it look, for heaven’s sake?”

Akitada and Yoshiko were still looking at each other. He saw the helpless tears gathering in her eyes and opened his mouth to reassure her, but it was too late. The tears spilled over. “I shall stay—as I stayed with Mother,” she said in a tone of utter hopelessness, half choking on the words, then jumped up and ran from the room. Tamako, with an inscrutable look at her husband, rose to follow.

“Now what?” said Akiko in an annoyed tone, staring after them. She started to get up also, clumsily, because of her pregnancy, and muttered, “Heavens! The stubbornness of that girl! She must be made to see reason!”

“No.” Akitada was up. “Don’t strain yourself. Stay here with your husband. You have done enough.” He headed out the door, pleased for a moment with the ambiguity of his words, but tension, and with it the throbbing behind his eyes, returned. He was not sure whether he was more frustrated by Yoshiko or her insensitive sister. At the moment he felt like blaming both for the strain between himself and his wife.

He heard Yoshiko before he reached her room. Her voice was desperate, high with passion, and carried quite clearly. “No! You are wrong!” she cried. “My brother has made up his mind against it. He’s the kind of person who despises men who are not as nobly born as he and thinks them no better than animals.”

Akitada stopped abruptly. His mind rebelled at her opinion of his character. He fought his anger. It was not true, of course. She did not know him, could not know how fond he was of Tora and Genba, neither of whom would dream of aspiring to marry his sister.

There was a pause, presumably for Tamako to respond, but she spoke so softly he could not hear her. Yoshiko cut back in with, “Honor? It is he who is dishonored by forcing me to break my word to Kojiro.”

Akitada bit his lip, then knocked.

Tamako opened, her eyes widening at the anger in his face. Akitada said stiffly, “Leave us alone.” Tamako flinched, then her eyes narrowed. She compressed her lips and left.

Yoshiko stood in the middle of her room, a very pleasant one as her brother saw, his glance sweeping over screens and painted clothes boxes, lacquered sewing kits and writing utensils, a bamboo shelf with narrative scrolls and collections of poems, and paper-covered doors to the outside. That she should be so unappreciative of the comforts provided for her angered him more. He glared at her flushed, tear-stained face and said coldly, “I shall not force you to remain under my roof against your will. However, in this matter both Toshikage and Akiko support me. I cannot imagine that your stay with them would be much more pleasant than putting up with me.”

Yoshiko stared at him. Slowly the tears started again. Her voice was unsteady. “I know. Thank you, Akitada.”

He looked away and glanced around the room again, searching for words. He finally said stiffly, “It appears that I cannot make you see that I have only your best interests at heart, and this naturally pains me. But if you decide to remain, there will be a condition. I will not tolerate your putting your affairs between myself and Tamako. Do you understand!”

She gasped and made an imploring gesture with her hands. “I… I didn’t intend … I am sorry.” Then she began to sob in earnest. Her words were so muffled that he could barely hear her. “I am sorry and shall obey you in the future.” She bowed, weeping silently. He could imagine what such a promise had cost her, and felt a little ashamed, sickened at having reduced his sister to this pitiful weeping thing—no matter that he had done so with words instead of blows; it had been just as effective.

He returned to his guests in a bitter mood. Toshikage was standing before the scroll of the boy and the puppies. He glanced at Akitada, but with great tact he did not ask about Yoshiko. Instead he said, “This is by Noami, Akiko says. What did you think of him?”

Covering his distress, Akitada became almost voluble. “A remarkable artist, but I did not like him. For one thing, he is insufferably rude. For another, there is something unpleasant about him. Did I tell you that he is painting a gruesome hell screen for the temple where Nagaoka’s wife was killed?”

“You don’t say! What a coincidence! Well, he is becoming very popular. I suppose his patrons think it’s artistic eccentricity. Will he paint a screen for you?”

Akitada wanted Tamako to have the finest screen in the capital, even if it meant paying an exorbitant amount to a man he instinctively detested, but he hesitated. “I don’t know. The thought of visiting his studio again appalls me. I am not superstitious, but I had the strangest sense of evil while I was there.”

Toshikage chuckled. “I have met him. He would make a fine demon, I think.”

Akiko yawned noisily and shivered. “How you men chatter! It is cold in here.”

Toshikage rushed to help his wife into her quilted jacket. “It is getting late and Akiko is worn out,” he said apologetically. “If things are settled, we will go home.”

Akiko was either too tired or had the good sense to say no more on the subject of Yoshiko’s lover. Leaning heavily on her husband’s arm, she waved a languid good-bye to her brother.

Akitada saw them off and then returned to his own room. The charcoal in the brazier had turned to ashes, and it was chilly. His head still ached, and he wondered if he was getting sick. He did not have the energy to call Seimei. Besides, the old man had been doing enough. Throwing an extra robe around his shoulders, he sat down behind his desk and tried to think. The meeting with his wife and sister had gone about as badly as he had feared. Although he considered his anger justified after Tamako had taken Yoshiko’s side against him, he dreaded facing her.

A scratching at the door interrupted his morose imaginings of what his wife would do or say to him after he had ordered her from his sister’s room.

“Come in,” he called, wishing whoever it was to the devil.

It was Yoshiko. She bowed very humbly. “Please forgive the interruption,” she said, creeping in on tentative feet, her voice toneless, her eyes lowered. Taking a deep, shuddering breath, she raised her eyes to Akitada and burst into speech. “I regret deeply having caused trouble for you and Tamako. Thinking of you as only my elder brother, I am afraid I forgot my duty to you as the head of my family. Akiko and Tamako have both reminded me that since I am unmarried, my first allegiance must always be to my family. I promise to accept your decisions for my future and to remain here as long as it pleases you.” She took another deep breath and reached into her sleeve. With trembling fingers she extended a letter to him. “If you please, this is for Kojiro. You can read it. It explains why I cannot marry him. Will you give it to him?”

Akitada stared at the oblong of elegant paper as if it were red-hot. He had triumphed over her willfulness, had forced her to break her word to Kojiro, but victory tasted as bitter as the ashes in the cold brazier. Yet he could not reverse his judgment. The man in prison was simply not an acceptable husband for his sister. He hesitated so long that Yoshiko’s extended hand began to shake and the letter slipped from her fingers. He caught it before it fell and put it in his sleeve.

“Yes. Of course,” he said thickly. “I… I am very sorry, Yoshiko. He knows already, for I told him. I wish things were different. You must see—”

She bowed without a word and left his room.

Akitada took the letter from his sleeve. It was not sealed. The thin mulberry paper showed the brush strokes on the inside. Yoshiko’s brush strokes were elegant and fluid, the hand of a woman of grace and culture. How little he really knew about his sister! A memory came into his head, of how he had offered to help her marry the man her mother had rejected! A foolish promise made out of love for the little sister who had years earlier brought him and Tamako together. Sickened, he laid the letter on his desk and rose to pace the floor.

Suddenly the room felt too close. It seemed to be pressing in on him, worsening his headache. He opened the shutters and walked down into the garden. The snow had melted, and he could see the shapes of the fish moving sluggishly beneath the surface of the small pond. As he leaned down to scoop a handful of dead leaves from the surface, the carp rose to his hand. Sorry that he had no food for them, he let them probe his fingers with gentle inquisitive mouths. Their touch resembled caresses. Had his father ever stood like this, alone and alienated from those around him?

When he returned to his study, his head still aching, he found Tora and Genba waiting. Caught up in his private thoughts, he did not notice right away that they sat as far away from each other as possible.

“We came to report, sir,” announced Tora stiffly.

“Oh, yes, the actors. Did you find them?”

“Yes, sir,” they answered in unison. Genba added, “They use a riverside training hall to practice. I was lucky enough to meet the lady proprietor in one of the restaurants.”

Tora made an impolite noise. “Never mind that obnoxious moon cake of a female! She knows nothing, but one of Uemon’s girls has promised to meet me tonight.”Tora smiled, stroking his mustache. “I’ll try to get the goods on their lead actor Danjuro. He’s a very suspicious character.”

Akitada’s eyes had moved from one to the other, trying to make sense of their words. Slowly he realized that something was wrong. They pointedly avoided looking at each other. Tora and Genba had always been on the easiest, friendliest terms with each other. What could have happened? He saw Tora looking at him expectantly and tried to recall his words. “Er, what do you mean, ‘suspicious’?”

Tora gave a succinct account of events as they led up to and followed his clash with Danjuro, skipping only over his stick-fighting ordeal and the cuddle in the alley. “So you see,” he summed up, “they all turned into clams when I tried to ask questions. And all because he thought I was a constable. Which naturally made me think he’s got something to hide.”

Akitada stared at him. “He thought you were a constable? Whatever gave him that idea?”

Tora reddened. “Can’t imagine. Must’ve been something I said.”

“What?” Akitada persisted.

“Well, he was giving himself airs about being the great Danjuro and told me that I was some lowlife who had insulted his lady wife.”

Genba muttered, “Which naturally he had.”

“Shut up, you,” snarled Tora. “You weren’t there. You were too busy ogling that fat cow to keep your mind on work.”

Genba glared. “I found the place first. And I get results without getting into fights and quarrels and abusing every poor girl in sight.”

Akitada had enough. “Stop this ridiculous bickering this instant! You can settle your differences later. What facts have either of you found out that links these people to the murder of Mrs. Nagaoka?”

They shook their heads.

“Nothing at all?”

“Well,” said Tora, “they were at the temple, and Danjuro is afraid of the police. Surely that—”

Akitada snapped, “You wasted my time for that? Actors do not have to be involved in a murder to fear the police.”

“Hah,” cried Tora triumphantly. “That’s exactly what I told the fellow! With my experience as an investigator, I told him, I know better than to believe actors and acrobats are law-abiding citizens. Nine out of ten times they’re nothing but thieves and harlots.”

Genba growled, “That’s a lie! And you’re a fool to give yourself away like that! Of course they wouldn’t talk to you after that. I’ve lived longer than you and met more entertainers. They don’t like the police because they’re harassed by them. Most of them are as decent as you and me. No, more decent than you, for most of them would never look down on a man just because he’s only a peasant or a sandal maker. Miss Plumblossom didn’t look down on you for being a deserter. She knew that the minute you opened your big mouth and told her you used to be a soldier like that fellow who sent you there. Only a low-class person mocks his fellow beings, and Miss Plumblossom is not a low-class person.”

Tora sneered. “Because she once slept with some fat bastard with a title? So have half the sluts in the Willow Quarter. Besides, the woman probably lies. Look at her! Who’d want to sleep with that? She’s as big as a bear and as bald as an egg. A man would be afraid she’d smother him if she got on top for the rain and the clouds.”