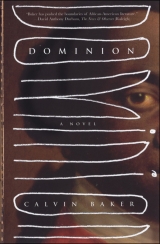

Текст книги "Dominion"

Автор книги: Calvin Baker

Жанр:

Историческая проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

two

The two men sat across from each other with the fire burning low behind them, looking at one another only tentatively. Although they touched often, it was by accident and caused them both some small embarrassment at first, until they grew used to it. Breaking the center chain was very simple. Purchase did this with a strong chisel and a good sharp whack from one of the hammers on a workbench in the barn. The bracelets, though, were another matter, and he was forced to work at them a long time with the smallest tools in his possession.

It was an admirable lock, and when he finally deciphered its clenching mechanism he would feel some small sympathy for his defeated adversary, for its maker had designed that lock with great care and deep insight and intended it to hold until whosoever had mastery of the key released it, but not before.

“How is that?” Purchase asked, pausing in his work to get a better hold on one of the shackles.

Ware massaged his raw flesh beneath the iron and answered, “Not bad. But I have lived with them awhile and am not the best judge.”

“Do you want me to wait so you can catch your breath?” Purchase asked, for he could see how the skin under the handcuff had been almost completely removed and what pain Ware must be in, despite shrugging it off.

“No. Better to go ahead and have done with it.”

Purchase resumed work, trying not to aggravate the skin under the irons, which was orange with rust around the wounds where the metal had contacted his blood. As he watched the stoicism with which Ware bore this pain and intrusion, Purchase felt a tremendous respect for the other man and his private travails.

Ware, for his part, looked at Purchase, and how deliberate he was with what was undeniably an unpleasant and rough business, and his affection for the younger man took hold as for a brother raised under the same roof, and even if they were very different men, they were bound together then nonetheless.

They went on like this, with unspoken tenderness for each other, as they shared a singular understanding until the lock finally revealed itself and opened. Nor when it was done did they thank or comfort each other, but took it each in stride as roles that might easily be reversed.

When the irons were finally off, Ware plunged his hands up to the elbow in a vat of water, washing the filth and dried blood from them. As he did this, Merian and Sanne came into the barn. Sanne carried with her a parcel of clean rags, which she had cut into bandages. When Ware took his hands from the water, she dried them and began to dress his raw wrists in the cotton.

Merian surveyed this scene and did not speak, but he was exceedingly proud of all his family. This, he thought, far surpassed any birthday he had ever celebrated before, even that original year of freedom when he was still in Virginia and first gave himself one, knowing not when he was actually born. He went carousing that year with friends until the celebration turned some unmarked corner and he was left very sore off from celebrating. He figured then it was because he had not done it before and so was not used to it, but soon learned that that was the nature of joy – a flying that could also turn full around if you took it out of sensible range.

He thought this year he had achieved perfect balance.

When Sanne finished dressing Ware’s wounds, they all returned to the main house, where Sanne had Adelia bring out food from the kitchen for Ware, which he devoured at first in a rush, but soon slowed down, seemingly full. When he had his fill of meats he took a very little bit of pudding and a half glass of cider to wash it all down.

“Are you feeling better?” Purchase asked.

“Do you want anything else?” Sanne wanted to know.

“I’m fine, I’m fine,” he answered them. “A whole heap better than before.”

“What else—” Sanne began, but Merian intervened.

“There’s plenty of time for getting acquainted. I think Ware might like to rest right now.”

Merian led him to an empty room above the kitchen and asked whether there was anything else he needed to pass the night in peace. The new arrival replied there was not, and very soon after Merian left the room.

Magnus, as he himself preferred to be called, looked around in the dark, staring into the edges and corners of the unfamiliar chamber, trying to grow used to the climate indoors again and to figure what sort of course he had charted – not knowing whether he would be received here or not, or why exactly he chose to come to this place rather than great Philadelphia, or even as far off as Boston, anyplace where he might blend in with the general population instead of stopping where he had. He wondered still whether the law might catch up with him – and if they had been pursuing him at that very moment they surely would have, for he scarcely finished the thought before falling asleep from tiredness.

After showing Ware the room Merian went to his own bed, where Sanne lay awake waiting for him. “How is he?” she asked when he entered.

“Fine as might be expected,” Merian answered.

“And you?”

“It’s a great day for me, Sanne. I never on earth thought I would live to see it. Thank you.”

“Well, what happens now? He just shows up a grown man, very likely wanted by the authorities, and you take him in?”

“We will see, Sanne.”

“What about her? Where is she?”

“He didn’t say, and I haven’t asked him yet,” Merian said. In truth, though, he knew what had most likely happened. The boy would have never left Ruth if she was still alive, not if he had suffered everything long enough to become a full-grown man and hadn’t left before that. “There will be plenty of time for questions.”

“Don’t you want to know?”

“Good night, Sanne.”

“And I’m supposed to just stand back, whatever happens.”

“Good night, wife.”

“Good night, husband.”

Merian woke the next day before the rest of the house stirred and went first thing to town, where he met with Content but did not tell him straightaway of the new arrival.

“If a man needed to get papers, Content,” he asked, “where would he go?”

“Depends on what he needed them to say.”

“That he was legitimate.”

“Legitimate what?”

“Legitimate free before the law.”

“Are they for you?”

“In a way.”

“Everybody knows you and knows who you are.”

Seeing no other avenue Merian confessed to the new situation on his place and slid a guinea across the table. “Can you take care of it for me?”

Content nodded that he could but asked Merian why he hadn’t come out and told him the thing to begin with. “It would be a lot simpler that way, Merian.”

“Don’t give me your lectures, Content,” Merian said. “I don’t see that it’s all so complicated now.”

“It isn’t,” Content answered. “It just would have been simpler the other way.” Content went to the door, locked the tavern, and had Merian come with him to his office in back. There, he took out a sheet of very fine writing paper, an ink pot, and his quill. He asked Merian again for the name of his son and began to write a letter stating that the bearer was a free man. When he finished, Merian asked him to read what he had written and, satisfied, expressed to Content his deep gratitude.

“You would do the same for me,” his friend answered him, pushing the coin back at him.

“Well, you and Dorthea ought to come out and meet him soon. Maybe this Sunday,” Merian said, as he stood to leave.

“We just might. But why not give everything awhile to get to normal out there first,” Content replied.

Merian tipped his hat to his friend and took his leave. No longer able to sit a horse as he used to, he climbed into his carriage and rode the seven miles back out to the farm, remembering his own first days of freedom, and his own fresh beginning in this strange new country, though he was not a fugitive as his boy was.

Sanne had given Adelia instructions to let Magnus sleep as long as he wanted and to see that he had whatever he required as soon as he stirred. When he finally did awaken, she went immediately to see to him. Being unaccustomed to service, he could not even think what a person might need brought to him first thing in the morning other than another parcel of sleep. “No,” he said, rubbing his eyes, “but I might like a spot of breakfast if that’s no trouble.”

When he went downstairs, she directed him to the dining room where the family ate, not knowing what his position in the house was and deciding to err on the side of generosity, as Sanne had always told her to do with their guests.

When he sat down she asked what he would like, and he responded that he wouldn’t mind some milk and biscuits. She then brought out to the table a breakfast of eggs and bacon, as well as what he had asked her for. He ate everything and seemed satisfied, but when still more biscuits and milk were put before him he ate the biscuits in a flurry of surprisingly tidy activity, then drained his glass of milk with one turn up to his mouth. The girl asked whether he would like more and he said yes. She filled his glass again and watched as the milk disappeared, and another glass after it, until he had drained nearly an entire pailful.

When it was reported to Sanne later how he had consumed an entire cow’s morning offering, she said that the girl should find out whether he required any special preparation for it, or if it was fine as brought to the table. Magnus told her any way he could get it was fine with him, and proceeded that first week to consume milk at a more prodigious rate than anyone would have thought possible.

Merian entered the dining room, just as Ware – as he would always insist on calling him – was finishing his breakfast, and asked after his sleep.

“It was very good, sir,” Ware answered, but did not tell him either on that occasion or any other that he preferred to be called Magnus and, in fact, did not remember ever being called Ware to begin with. None of this mattered to Merian, who had given him the name in the first place.

“Is it great yet, though?” Merian asked. “I want you to let me know when it gets to be great.”

Magnus looked at him but did not know what he meant. “I’m sorry?”

“I want to know when your sleep start to feel different. After you wake before first light and realize you can sleep all the day and won’t nobody say nothing. Then again when you realize you still got to get up around first light if you want anything from the day. The first time you sleep a night knowing the day before you and every one after that is yours. I want you to tell me when it starts to feel great to you.”

Magnus smiled ruefully, unable to imagine that such a moment might ever come or that such an idea was anything but an old man’s fanciful remembering of his own past. “Well, they might still come after me.”

“No, they won’t,” Merian said. “Nobody is after you. And if they were they surely won’t look this far from where you started.”

“I don’t put it past them,” Magnus said. “Sorel hate to see anything get out from his control. That’s why he wouldn’t let my mama buy us out in the first place, on account of that would be one more thing in the world, besides the sun and what-all, that he didn’t have say-so over.”

Merian nodded and said nothing, not wanting to interrupt the other once he had started talking – for fear he might never tell what it was he had to say. He did allow himself a question, though. “How is your mama?”

Magnus looked at Merian, and it was hard to tell just then whether there was not hatred in his eyes for the man who had given him life and was providing him shelter. Whatever it was passed quickly, and his face sloped toward sadness when he replied, “She passed on.”

Merian was sadder than he had thought he would be when he first suspected it to be the case, and sadder than anyone would have ever been able to tell him he would be to hear the tragedy of a woman he had known so long ago. He withheld his emotion from Magnus, for it was something he found he did not understand entirely, and that was not a pleasant sensation or knowledge for a man his age to discover about his own inner life: that his heart it was still very cunning.

He was pleased, though, at the way Ware had put it, thinking that is exactly what Ruth would have done, as if she planned it out long ago.

“When?” he asked.

“This November past.”

“I see. How did she go?”

“Her blood. It turned sweet.”

Merian knew this to mean she had sugar in the blood, which was common in older people, so that they could never satisfy the craving for sweets but were pitched into distemper immediately upon having them. He also knew it was said to be caused by a love that had been thwarted or never satisfied in youth. But he was happy to know she had died in old age, for she would have been nearly fifty years old, which he reckoned was as much time as was allotted most. His own days he had grown greedy and less sensible about, counting them as his getting-back time. When he first found freedom he had not been that way, but he was not always a stranger and foe to bitterness in his later years. He figured if he could get back another twenty or so, he would be just even.

“She go peaceful?”

“Peaceful enough.”

“You know, your mother, she was something else,” Merian said, for he had not marked her death and wished to remember her now that she was present before his memory’s eye.

“I know what she was like,” Magnus said sharply, with the same flash of intensity about the mouth and eyes that had appeared there before.

“I remember when I first laid eyes on her,” Merian continued. “Both her and her mother came home with Hannah Sorel’s father one day, and he installed the mother as cook. Ruth was just a little girl who didn’t even speak English yet – no more than hello, and besides that nothing but pure Congo, or whatever it was in the port she was first from. You could tell she was quick, though, because she picked up better English than most people born to it by the end of her first year. That’s just what it seemed. It was even more striking because her mother never learned it at all, beyond the few words she needed to do her job. Then the old man come to find out she spoke schoolmaster’s Dutch on top of that.

“The original house there was called Colonus and was fairly small, so the two of them shared a room just across the hall from me, and I would see both of them all the time. At first Ruth was so little that didn’t nobody pay her any mind aside from, Well, she sure is one fast study with English speaking.

“I had never given her any more mind than anybody else anyway, but one day, after I came in from working, she was in the hall playing with a puppet she had found to amuse herself with, and she looked up at me as I was going into my room and asked, ‘Where Jasper mama?’

“That was the first thing she said to me, and the first time I even knew she knew my name. I just smiled at her – she couldn’t have been no more than eight or nine – and went on to my room. But I was aware of her from then on and, like I said, she was something far out of the usual.”

The two men were silent then, thinking about Ruth. Magnus also thought of Merian as real flesh and bone for the first time since arriving, after nothing but having heard of him for so long. Merian’s open affection for his mother made the younger man more trusting as well.

For Merian it was the first time he had talked about Ruth since the last time he saw her, and it did him good to speak about her. He would have taken Magnus into his home even if he wasn’t his son but only as Ruth’s boy, which, in truth, is how he saw him.

“You don’t remember me, do you?”

“No more than you do something out of a dream,” Magnus admitted, then worried he might have sounded too hard, “In my mind, yes, but I know or think I know it’s just something I been told. The same way you and Mama say they used to call me Ware.”

“Wasn’t used to call, it was named,” Merian said. “Tell me how you came to get away?”

“No different than anybody else,” Magnus said.

Merian nodded. “Here,” he said, holding out to him the papers Content had written up, which testified that their bearer was his own proprietor. “If somebody aim to do something anyway, they won’t be much good, I imagine,” Merian said. “Then again, if somebody aim to do something, you deal with that the way you must. Things haven’t turned out as bad here as they are in Virginia and down the coast. It ain’t what it is in some other places,” he allowed himself optimistically. “There’s a few free African families around here, so it ain’t so strange a sight for people, and they let you go about your business same as any other man. So what you can expect, if this is where you decide you want to be, is that everybody will act toward you the way you act toward yourself. I can’t tell you what way that should be. I don’t know, but the way I would think about it for myself, if I was in your shoes, is: I started in one place and now I’m in another and aim to be all right there. Simple as that. No different from anybody else in these parts.”

“Is that simple?” Magnus asked

“Anyway, it says you’re free, and if you ever need it there it is.”

Magnus took the papers without comment and looked at them. He was touched by the gesture, but it was holding the paper that made it all real to him, and he did not care if they were legitimate or only fakes worked up to fool constables and sheriffs. What they said was the truth and very real – he was a man free of any other’s hold, and the sole foreman of his soul and being besides the Almighty. That was real as sunshine, and it would never be different. Even if he acted before Merian as if he had carried the papers himself the whole while and only dropped them in the road, he was very much affected.

Merian stood to leave and give Ware the day for himself to do whatever he thought fit. He moved by then like a man who was at ease with himself and who he was in the world. It would be a great many years before Magnus, as he was called, gained the same assurance, but once he did he moved with much the same bearing as his father.

Merian, as he left the room, knew Sanne would raise the devil about it, but for him there was no choice but that the young man, if he wanted, was welcome to stay on at Stonehouses.

three

His terror that second night, when he realized his condition, was abject and complete. He was not normally a sensitive man, but his teeth chattered against each other and his legs locked at the knees as he thought about what challenges lay before him. His manufactured freedom papers were clutched to his breast, making real all that had changed since he arrived there, still he was unmoored by this new status, not knowing whether he would prove master of the thousand strange contests it would pose for his every fiber.

After he had stayed there six days, Merian suggested that work might be the best thing to set his mind and body right again. Magnus agreed to try it, and as he worked out in the fields the next morning, alongside Merian, the older man asked again how he was faring.

“Everyone here treats me fine,” Magnus answered.

“That’s not what I mean,” Merian said. “You will know it when it happens.” He walked away then, leaving Magnus to puzzle just what he did mean.

That night, when he tried to find sleep, Magnus instead found himself disoriented and dizzy to the point of losing his dinner in the chamber pot. As he told Merian the next day, all he felt was that he was in a different place, and he could not stop thinking about Sorel’s Hundred and all he had known there.

“Do you know the story of that place?” Merian asked him then, sitting down to the midday meal.

“Just what I witnessed,” Magnus replied. “I didn’t know there was any story about it to know.”

“You never knew about the old man?”

“He never affected me.”

“Well, he came over here from England – it must have been a full hundred years ago now – and when he bought that land there was nothing at all around there, or anywhere else in all of Virginia. Even so, he thought to name his new property, and the name he thought to call it by, as you well know, was Colonus.

“He would stand out on the porch, after the house grew to a certain size, and stare at all that virgin country around him, with no idea what lay beyond the other side of the river, and get the most forlorn look on his face. He would turn then and say, to anyone who happened to be in hearing distance, ‘See how Edenic it all is.’ That was his word. ‘We are in exile, but only to be purified. If we let ourselves be cleansed without despoiling it, we will be allowed home again.’

“Then, not too long after the time Ruth and her mother came on the place, he started one day to call the old woman Antigone for no good reason. ‘What are we having for dinner this fine evening, Antigone?’ Or, ‘How does the weather agree with you this afternoon, Antigone?’ He claimed that if his wife had agreed to it that is what he would have named Hannah. ‘I can’t think of any better name for a daughter than that,’ he said.

“Nobody paid it much mind at first. Some men rename a slave at the drop of a hat, like a name is nothing more than a plaything. We just thought it a little peculiar, because he was not that way. When time came for Hannah to marry that Sorel fellow, he gave them some land out on his property to build a house and sent me off with them.

“It must have been the night before we were set to leave, and I was going into the house when he called me out there and told me to sit with him. Now that wasn’t very strange either, as he always had somebody to sit out with him after his wife died. What was strange was when he started talking that night, and wanted to tell me it seemed like everything he knew, starting with where the name of his house came from.

“‘Once, long ago, there lived a great king, and those are precious few, who committed two gross and unforgivable crimes, and when they had made him poor as a beggar for it, his people’s gods let it be known that Colonus was the place that would receive him in his old age.’

“When he finished telling me that I could see how very old he had grown, and I thought perhaps he was trying to remember the rest of his story, but he just looked at me and said, ‘It is terrible to be loved by God. Most cannot endure it, Jasper. But name all thy houses Colonus and all thy daughters Antigone, and thou shall never know sorrow.’

“That nearly brought tears to my eyes, to see how scared he was out there on his place; and that it would always be strange to him, even though it was his house. His advice, though, seemed sound as any I ever had. ‘Name all your houses Colonus and all your daughters Antigone, and you will never know sorrow.’”

That night when he went to bed, Magnus lay awake for the same long time as before, staring at the beams of the ceiling in his room and thinking of the last months. But instead of fearing what trial could possibly come next, he saw the good fortune he had had and the strength of the way he had acquitted himself. It felt then as if a great pressure was lifted up from him. He began to see that strength was as much a part of him as the fear he had been carrying since he ran from Virginia and had nearly been consumed by on the journey to Stonehouses, when he spent every day in hiding, waiting for nightfall so he could move on again. He began then to laugh, not altogether maniacally, but he had a good roar at all of it, and when he finished he was in tears. He fell asleep quite peaceful, and the next morning before Merian asked him he could say for himself, “It is good now.”

Merian was pleased when Magnus announced that he had finally put his fear aside. “It is a special day when that happens,” he told his sons, as Purchase left for his shop and he and Magnus went on to the fields. “It is like becoming a man all over again, when you come to know you’re alive but will eventually die and so start to celebrate that. Everything changes. You start winning the struggle, because it is your own.”

Magnus did not feel anything so profound as all that had happened to him, but he told Merian he would take him at his word, as they went to work the fields with the hired men.

The previous days Magnus had worked lethargically, barely keeping up with the slowest man out there, but that afternoon when he worked he produced handsomely, thinking he owed Merian something for all he had given to him, and the only way he could repay him was with good labor. He was not invested in that land, but he worked as though it meant something to him, and as the days passed he found he was beginning to grow attached to the people of Stonehouses.

Still, he did not sleep as well as he was accustomed to. At the end of his first week, when he was finally able to drift off for more than an hour or two, he had a strange dream that was very haunting and disturbing to him. In it he pursued a woman continuously but never caught up with her. He would run faster and faster, but she would always manage to elude him, until he grew frustrated and could not remember why he chased her in the first place. “Go on, you old witch,” he called out in the dream. “I don’t want you no way.”

She laughed at him when he said this and began taunting him. “Even if you did catch me, you still couldn’t get what you want.”

“I don’t want nothing from you,” he yelled at her again, then added, as if she were an animal he could command, “Pass on.”

“Oh, yes, you do,” she countered, raising her skirts up so that he could see all her private parts.

“Man give the meat,

Man give the gravy,

But woman give the milk

And woman give the babies.”

She laughed and dropped her skirt.

“Get away from me, you evil thing,” he called out. She continued laughing at him and ran off again. Despite himself he started to chase after her, even though he understood by then he would never catch up.

He awoke frustrated and understood from the dream that he was meant never to have children. This in itself did not play at his emotions, because he had never been overly drawn to children in the first place and so could not see any shame in not having them. As for women, he had known several at Sorel’s Hundred and the surrounding plantations, but never one whom he would have thought to call a wife. For to tell the truth he could not see the great pleasure in being so intimate with anyone and sharing all your thoughts and time. When he did take a woman, it was because nature could not be suppressed, or when he found one pleasant and thought to spend a season or so in her company – but not longer than that, for it began to weary him. He had no need for children and marriage but preferred his own solitude and thought, when there was the luxury for it, which was but very seldom for family men. That was why the dream disturbed him even more, because he did not think it revealed anything true but was only a deep taunting, and he worried someone had put a root spell on him to make him want what he did not.

After dinner the following day, Magnus was still trying to puzzle out the dream when Purchase asked him whether he would not like to go for some amusement.

“What is there at this hour?”

“I thought you might fancy a game of cards.”

“I don’t have money, but I’ll join you for company if you don’t mind.”

Magnus was not generally one for drinking and the concomitant sins, but he appreciated the offer from Purchase, and thought it might do him well to go out in the air. The two brothers went to the stable then, where they saddled horses and went off in search of entertainment.

The town where Purchase took Magnus was not Berkeley, though. Rather, they rode some five miles in the opposite direction to a small building set off in the woods with nothing else around it. Inside men and women of all stripes and countries milled around, and it was easy for Magnus to see what kind of place he had been brought to, even if he had never been to one before. It was also immediately plain that Purchase spent a great deal of time here, for the proprietor seemed to know him well.

The two brothers ordered drinks from the bar and sat alone with each other, not speaking very much but watching the room in silence. When two men sitting at a card table went off with a pair of the harlots, who had procured their attention beyond what the cards could, a place at the gaming table was free for the first time.

“Would you care to play?” Purchase asked.

“I don’t have money.”

“It is my invitation.”

They sat down with the four already present: a Creole and an Indian, who didn’t seem to know either each other or anyone else there. In addition there was an Englishman and an African woman, who seemed to be partners of some sort or other. When they sat, the woman began the deal, but neither the Creole nor the Indian had very good cards and soon put down their hands. Purchase proceeded to bet with abandon, studying the African woman very carefully, as the Englishman made friendly talk with Magnus. When there were as many coins stacked on the table as he had ever seen, Magnus had sense to put down his cards and watch the other players, knowing that the monies he had already lost were not his but Purchase’s.

Purchase, though, did not seem to care about the coins and continued to put more into the stack in the center of the table, until the Englishman also withdrew and there was only Purchase and the woman left in the game.

By now the men who had sat there earlier were finished with their business and took seats at the bar to watch the card game unfold. “She’ll have his very skin before long,” one of the men said, looking at the cards on the table. At this Purchase cut his eyes menacingly and pulled a pistol from his belt. “Not before I’ve had yours if you keep flapping,” he answered, leaving the gun on the table pointed at the other man. The man who had been threatened was quiet after that, as much from fear of Purchase as the fact that the gun was made of unmixed gold. “It will put a golden bullet in you too,” Purchase said, looking steadily at his cards.

Magnus could tell very little about who had the better hand from the cards that showed on the table, but when the next one was revealed, he saw Purchase’s face slump and the woman begin to glitter. “It’s all right, Sugarloaf,” she said to him. “If you lose I’ll let you stay the night with me in my room.” The Englishman who had been her partner was not pleased to hear her talk so saucily, but he held his tongue, waiting for the last card to be turned over.