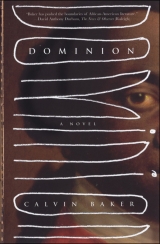

Текст книги "Dominion"

Автор книги: Calvin Baker

Жанр:

Историческая проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

When he finished, a great seal marked the center of the garden where Sanne still planted vegetables and herbs for the house. Now the movement of hours and seasons would be marked there as well, no longer a crude thing measured out in plantings and the metronome of the harvest, or the length of his shadow as the sun rode the back of his labors. For he had installed a sundial at Stonehouses, and it was more than mere decoration; he had brought time and chronology onto his property and into his possession.

What he measured that night, though, was less time than the sum of his dealings in his early days, which he did to appraise how much he had been gaining or losing. What he counted was zero parents, equal siblings, two masters and one mistress (depending on the count), an untold number of voyages, three houses built, two languages learned (though only one remembered), a solid handful of dependable friends, two male children, and two wives.

Of the future he knew not, and tried not to give much care, knowing only that he could not foresee it, but that things would pass in their time and work either for good or ill, depending on other devices.

These were the reckonings of Jasper Merian, after a half score of seasons had passed at Stonehouses, in the ancient days of Columbia, in one of those districts named for Carol Rex, before the nameless Indian battles, in the beginning, second immemorial age, in America.

II. age of fire

one

He is a forger of metal with no interest in the ground except its hidden ores and nothing of the plow except the strength and sharpness of its blade. He stands bare-chested from the waist up and, you can see, he is black as pig iron, or molten just after it is quenched. All except his eyes, which are light as wheatcorn. They belong to no one anybody around here has ever seen except he himself, and it comes down that he was not born with them but that they turned so from the intensity of his gaze into the furnace. He seems blind standing there – mute. Preachers will come one day to lay their hands on him, to release whatever has taken possession of those orbs, and women as well, who hope to know what lies behind them.

He keeps his stare fixed to heaven just now, as a cluster of white comets passes over the sky like angels, before turning fiery bright and speeding toward the lower reaches of the divine universe, right to the illuminated edge of this world, where they become blue-lined and red centered as God’s own heart worked in a blast furnace, before burning out and disappearing somewhere in the forestlands below.

He marks the spot well, etching in his mind the exact position in the mountains where the specks of light were last seen, then saddles his horse and sets off in discovery of the fallen bit of sky.

* * *

He journeyed three days and two hundred miles through the woods, without food or water for either man or horse. The trip, so says the lore of that country, would have taken a mere two days at the clip he rode and the animal flesh he made it upon, but the horse did fall of thirst in the last thirty miles and the man would not abandon it but carried him the rest of the way. This much was not true. The people of that country are well-known liars, though, especially as regards their history – making everything reflect well on themselves and region, but castigating all that might betray any secret weakness or want.

He arrived at the place he had marked, deep in an uncharted desolation of black pines and walked through their shadow nearly blinded, so little light penetrated those branches to reach the earthen floor. For what he searched, though, he did not need light but could find it even in the bosom of the darkest cave with his eyes bound. He sought as much by his nose as his eyes. When he smelled the odor of iron he knew his hunt was nearly complete, and he kept on until he saw the first dark rock, two fists in size, with a blue scrim from Heaven all around it. He touched the grooved surface and found it still cool as the roof of Heaven itself. He picked it up, placed it in his bag, and went on, until he had collected them all like a goose hen shepherding her flock. The bag weighed near a hundred pounds when he finished, as he lifted it up like a hay bale over his head. He went back then to the exhausted horse, whom he led at a gingerly pace, no matter how much he desired to be back home with his newfound treasure.

He knew the value of the rocks from the first, but not yet what he would make with them. That night as he rested it was revealed to him in a dream, and he rose and woke the horse, and the two of them began to fly toward home.

When he arrived back in town it was morning on the clock but not yet in the world, and he went on to his workshop, where he barred tight the door. The oven was still warm from the day before, but not hot as he needed it, and he spent hours stoking it back up to its maximum hotness. By the time he judged the furnace to be ready it was dawn, and one of the apprentices knocked at the door. He warned him off, to be left alone with his labor. The others came soon after, but he no longer bothered responding to their knocks and whistles, because he had started the rocks and watched them steadily without moving. When they were melted down he separated out the impurities, which were miraculous few, then fired the metal again. It was pure steel, like nothing the earth produces. When it was ready to be molded, he took it to his anvil and began working it into form with all the passion of force he possessed, raising and lowering the hammer onto the fired rock until it began to have shape and meaning beyond heat and mere metal. The sweat on his brow poured from his concentrated thought as much as from the furnace, but both commingled forms of perspiration evaporated almost instantaneously. He felt dry there in his cocoon of work, but to an outsider looking on he seemed to be covered in a cloud of steam.

After he had beaten a rough shape, he added to it a thin strip from another of the treated rocks, then hammered them until they were fused as hand and arm. The sound of his hammering, a familiar noise in the town, rang out that morning with a clarity and intensity that made passersby stop on the sidewalk to listen as he worked. Each time he drew the steel from the fire the metal screeched as it was being taken away, as two solids or else two similar elements crossing each other. Indeed, men who were later cut by it invariably described both the blade and the resultant sensation as a deep, mineral scalding.

Satisfied, he quenched it all in oil and left it to cool. In time he removed the blade and studied his effort, then fired portions of it again at various temperatures, hammering away the minuscule flaws and imperfections but also strengthening the metal a thousandfold more. He repeated the cooling, this time slackening the heat in water that had been mixed with certain liquids from his workbench.

He finished it on the second morning and quenched the whole thing in the vast vat of rainwater at the center of the room. He then took a stone to file and sharpen the edge, but found it was already dangerous to touch. He tested the edge and the tensile strength and was deeply satisfied. When one of the assistants knocked at the door this time he unbarred it and allowed the other man to enter.

He had worked until daylight pulled his head up to the horizon, just as the morning star, Venus, disappeared under the summit of the mountains, and he held the sword by its hilt up to the sun to see clearly what had been created in his furnace. It was perfect. Or nearly so.

When Charlton, the young assistant who was in charge of keeping the fires going, entered that morning, the first thing he noticed was the motif radiating out from the center of the sword, like patterns on Damascus steel, as it rested there on Purchase’s bench. These were not ordinary etched formations, though. People lucky enough to view it over the years all claimed they saw different things there, but even the wisest men and women could only see what they already knew. The majority saw nothing at all. What Purchase and his assistant both saw in the metal, as it cooled from its own creation, neither would confess to the other, for it was the entire world and future of the not-yet-conquered continent.

First was Auriga, called the Charioteer, who was the son of Hephaestus. There were then the instruments: Caelum, known as the Sculptor’s Chisel; Pyxis, the Compass; Sextens and Octans; and Norma as well. Great Fornax adorned an edge, as did Scutum and Horologium. Andromeda did burn brightly, and Ara, that most ancient altar, was there like a jeweled inlay in the metal itself. The celestial birds were present in pairs, Tucana and Aquila, the Eagle; Corvus and great Phoenix, though this was the only thing that might be called a blemish on the blade, as it was the same purple color of that creature in life, and was in fact the strongest metal, standing hard at the tip.

Delphinus played with other lighthearted beasts. Ophiuchus was present with his snakes, and Draco, the Dragon, appeared to turn, as it does in the night sky. Old Boötes drove the Bears as e’er he will – until the polestar turns away.

He saw Adam and Eve and their children, whom he did recognize, but hundreds of other people he did not. He saw in fact whole peoples who seemed strange to him and so could not make out their actions, only the ones he had already heard tell of. But everywhere on it he saw hope.

Down, not far from the base of the sword, Purchase Merian saw a man who was undoubtedly his father, Jasper; then himself. There were other figures as well near to them, but when these two appeared he nearly dropped the metal, for while the others were all strangers or only distantly known, these two stood so forcefully and lifelike he recognized that it was work even beyond what he could create and knew he held what had been blessed by God.

Besides his own hidden history he also saw a face that was clear and knew it was another close to him, though he did not recognize the man. He next saw the history of the country, from the explorers Cabot, Columbus, Balboa, Magellan, and Raleigh in their armadas first sailing, and the king’s chartering each of the colonies one by one. He saw as well fantastic inventions that he could not decipher from the more mythic things that adorned the blade. Had he an interest, he could have counted and named the great artists and scientists of the land and even its immortal bards. Of the philosophers there were not a great many, but its generals were numerous and mighty.

He also saw wars. He saw them first in what he recognized as the African and European lands, and he saw the Indian conflicts, ending with that race sent on a great trek out of their countries. Nearer he saw a war between Englishmen and another people who seemed much like them. Deeper down the blade he saw war again in Europe, that conflict then spilling off and onto all known parts of the globe. He also saw wars with the strange races he did not recognize and could not name, but that his countrymen did fight with them.

Next he counted men he did not know but could tell were to be the great leaders of the colonies, and of them were every race of men, including some he had not seen before and could not recognize. His eye did stop and go back, though, when he realized how close was the first of the mighty wars imprinted on the sword, and this he surmised was the reason for it being called into being.

When he could see no more, as the motif faded at a point and would not reveal its mysteries, he bade Charlton to hold it and feel its faultlessness, but the instrument was too heavy for the boy. One by one the rest of the workers entered the shop that day and marveled at what Purchase had created in his sequestered fever, but none could lift it, nor could any decipher the legend that ran down the center of the blade.

The sharpness, though, was evident to all. One man touched a solid iron bar to it, which was split evenly in two. The same was true for paper, hair, and even rock. Nor did the blade dull. When he asked that they try to break it, they all balked, not wanting to harm anything so lovingly crafted. In fact none would approach until Purchase offered a reward for whoever could break that steel. Each man tried it then, but none of them could succeed. For Purchase had made a perfect sword, which he told all who would listen was the only need it had for existence, though he knew by then it would eventually be part of an altogether different and very sad business.

Defeated in their efforts to break the blade, the other men retired, each speaking in awe of it – most of all the master smith who had been first to teach Purchase about fallen metals. He then spent the rest of that day creating a scabbard for the weapon. Although the scabbard was itself a fine item of worthy craftsmanship, and even beauty, it was quite plain compared to the sword. Nor did Purchase see any reason it should be any other way. He wrapped the entire bundle in a piece of handsome fabric, then swaddled it again in coarse burlap to protect it. When he had finished, he bade an assistant bring his horse around.

When the boy appeared with the animal it was already nearing darkness, and Purchase boarded it in one graceful motion, holding the package in his hands. He set out briskly for Stonehouses, where he was expected.

He arrived just as the shadow across the sundial out front spread into general communion with the shadows around it, and the thumbnail of a sun, which had held up just long enough for him to say he was there before sundown, vanished.

He stabled his horse, rubbing it down a little before entering the house through the kitchen, where Sanne’s great oven was filled with foods. Before he even opened the door, he could feel the warmth from the other side of the wood and smell that his mother had been cooking all day. Inside he found Adelia, the girl who helped Sanne with the house chores, stirring a large pot as he greeted her.

“They were waiting for you to eat,” she said, as he made his way to the dining room. There he found his parents, as well as Content and Dorthea, several of his father’s friends, and their immediate neighbors – except Rudolph Stanton, who never mingled – all gathered to celebrate Merian’s birthday.

Purchase first greeted his mother, then all their guests, as his father watched from the chair where he sat. Finally he went to his elder.

“Since when is sundown half past eight?” Jasper asked, looking at a watch he had bought some years before. “You know how we appreciate punctuality.”

“You have my profuse apologies, Papa.”

Purchase knew his father’s moods by now, as well as how best to avoid them, but tonight he found occasion for good cheer, seeing that he was not intent on punishing him for his tardiness. The two men clasped and he bid his father a happy birthday and good health. Adelia then came out and Sanne announced dinner to be ready.

The guests sat down at a table of warm cherry wood, which worked on a scheme of folding and expanding sections that, when let out to its full length, was big enough to accommodate all the guests comfortably. The table was expanded that evening the entire length of the room and laid with hot dishes of venison, beef roast, ham, turkey, duck, partridge, potatoes, yams, green peas, and warm bread. For dessert there was pudding, apple pie, and cobbler.

Afterward the cider and wine continued to flow at the table, with everyone drinking and enjoying themselves tremendously. Tea and coffee were served at the end, after they sang in that most comfortable hall to Merian’s health and grand hospitality.

When everyone had satisfied himself with food and drink, and they had cheered their host sufficient enough for a king, they began to bestow gifts upon Merian to commemorate this day of joy and feasting, for he had been on the land then some twenty-odd years, and could say he was a man in old age. The exact number he knew not, but that it was around fifty. Stonehouses was known by then across the county, and his years and prosperity there had surpassed even his own expectations. True, he was frustrated in the desire to keep expanding his lands, but he had done well, bringing wealth enough to his house, and counted his time now in blocks and cycles of years instead of a single calendar turn. He was happy with what he had wrought and been blessed with.

His only living sorrow was in his son Purchase, who went steadily in his own direction, and that never closer to Stonehouses and the hearth but farther away.

First Content and Dorthea presented him with a cask of the best brandy sold in the colonies, and Merian was much pleased. Then there came a French hunting pistol from the chandler, who over the years he had grown, if not fond of, at least able to bear on friendly terms. “It’ll not backfire on me, will it, Pete?” he asked, to gales of laughter from all present who had ever had dealings with the man. He was then given a hat by Sanne, that was very dear, and he was a man at ease and good comfort.

When he thought he had received all his presents, he smiled and lifted his glass to the assembly. He did not begrudge his son not giving him anything, as such notions are not held in spite among members of the same family. No he was not sorrowed.

Purchase, however, came forth then with his present and placed it before Merian, who smiled with abundance and gratitude even before opening it.

When everyone saw the size of the package from Purchase, they all pressed near to watch as Merian undid the wrapping. After the cloth flew away the entire room held its breath as they looked on the scabbard, for it was beautiful in itself. Merian closed his hand around the sword’s hilt and drew it forth. Purchase himself was apprehensive, remembering that no man in the workshop could lift it, but Merian pulled it forth quite handsomely, as if he had been handling swords his entire life.

Everyone in the room looked at the metal when it came forth among them, and the wondrous flash that danced in the light, and each of them let out the breaths they had been holding, as if pining for something or someone. Jasper himself looked at it and saw his entire history written on the blade: first were two people he could not make out fully but knew instinctively to be his mother and father. He saw next the Sorels, and he saw Ruth, and he saw Ware, called Magnus, though both of them were, to his mind, abstractions. Even Ruth was not as he would have her be but much receded from his mind’s eye – so that he saw very little of her when he tried to look there, though he did try sometimes. On the sword she was bright and perfect, and he began thinking again of those lines that had nearly tied him down all those years ago on the road out from Virginia.

He saw the gods of a strange people, as well as the same Adam and Eve that Purchase had viewed. There was so much there that, as he read it all, he allowed himself a rare moment and wept, bedazzled both by the sword and that his son had thought so lovingly of him.

His chiefest pride was in knowing that Purchase had made it, for everyone could see it was of a craftsmanship hardly seen, either in the colonies or, said one present who had been there, in Europe. For the sword itself, he was a farmer and sometime carpenter and housewright, with no pretensions to anything else in the world, besides that he was lord of Stonehouses. He was a man of peace with no need of the blade. Nonetheless, this one did take on a place of utmost honor in his home, and he embraced Purchase again. For he was so happy his son could do such things and that it might mean he intended to do all right as a man in general.

All the men present then tried one by one to lift the sword and found they could but only stare at it, resting there on Merian’s table. This was well and good, for if anyone could have moved that magnificent gift, even the most honest among them would not have hesitated to steal it.

Sanne kissed Purchase for doing so grand a thing for his father, and she too beamed with pride at her son’s ability to turn rock into something so wondrous with nothing but his skill and the furnace.

After the gifts had been bestowed, they drank another toast as night grew real, and it was soon time for the guests to depart. When their friends had bidden good-bye and were safely on the road again, only the three Merians and Adelia were left in the house. There was then a knock at the door. As Adelia was in the kitchen, Purchase went to answer, to see whether it was one of the guests returning for some forgotten trifle, a latecomer, or one come for another reason entirely.

When he opened the door he saw there a very tall man who seemed vaguely familiar – for he had seen him in the sword – although he had never met him before in life.

”I’m looking for Jasper Merian,” the man said, holding his road-beaten hat down over his hands.

“Who should I tell him is calling?” Purchase asked, wondering that one who looked as lowly as the fellow at their door should have come to the front and not gone around to the rear of the house. “What is thy name?”

“Tell him it is someone from Sorel’s Hundred.”

Purchase nodded and went back inside to his father.

“There is someone at the door who says he’s from somewhere called Sorel’s Hundred and claims to have business with you,” Purchase announced to his father, after reentering the dining hall. “Didn’t seem to mind that it’s well past normal visiting time.”

Merian excused himself and stood to go to the door, as his wife and son milled there waiting to see who this late arrival could be. When Merian returned, he held the other man with great affection and introduced him to the two in the room. “I’d like both of you to meet someone very dear to me, who I have not seen in a great many years,” the old man said, presenting the stranger to his family. “His name is Ware, though he is also called Magnus, and he is my son. You can see that, because he is punctual.

“Purchase,” he said, leading Ware over, “this is your brother, even if you never knew you had one.”

This was not entirely true. Sanne had told him on a couple of occasions, late at night when the two happened to meet up in the kitchen or else were otherwise awake when the rest of the house was quiet, that his father had whole secret lives she knew but little of, and one of them included another wife and child. This, though, was first proof to Purchase of his father’s life before them. Still, he went to Magnus and embraced him as bidden, and the affection between them was very natural.

Ware, called Magnus, stood there in the center of the great room and received his brother’s embrace. He would have returned it but could not hug him back, because his hands they were still shackled.