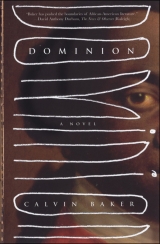

Текст книги "Dominion"

Автор книги: Calvin Baker

Жанр:

Историческая проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

five

The house grew and the farm grew and Ruth Potter bore the yoke and burden of domesticity – both in the field and on the road – and Sanne and Merian began to thrive and feel at ease in the clearing that was the boundary line of creation. In the corner of the room nearest the door the belly of the stove grew; and in the fields maize, which would fill it with meal in the winter months, reached ever skyward.

At trading that year Merian acquired a cow that was not too badly used, a pig for the slaughter, and several chickens, which would give them eggs. He also bought sundry items for the house and farm, including a large tin tub, shoes for both husband and wife, a dress for Sanne and a peck of apples for Ruth Potter. When the accounts were said and figured, he owed no one, and still had monies left for the first time and did not want for anything.

From their private garden, Sanne pulled tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, okra, yam, pear, various berries, greens, onions, and other herbs. Merian saved from the harvest a separate lot of America corn for seeding in the spring, tobacco for his own personal consumption, and the hay he had planted in anticipation of acquiring livestock. Sanne prepared preserves of the berries and pears and helped her husband in digging a root cellar at the side of their house to store their other surplus.

As the harvest came to a close, Merian and Ruth Potter went to the mill with the maize they would need for the year to have it ground into flour. When they returned, Merian noticed the house had grown hotter than any day before, even during the height of the southern summer, and he could not determine what the reason was until he saw the little stove his wife had built was fully fired and glowed, waiting only for something to give its heat and warmth to. She provided it with a pan of bread dough made from the new flour, and a pie made of berries she had set aside. The house filled with the smell of baking bread and sweets, and Merian thought he had never in his life had it as good, though his back ached as much as he could remember.

Still, he knew this was his own farm and labor given for his sustenance and his new wife’s, a thing which none but the most rotten man could begrudge. They basked that night in comfort from their toil, and neither thought of any of the other rooms, in times recent or far distant, in the houses and halls of their memories, they had inhabited before.

By the time the caravans that headed west each year started out that season, the Merians were already well ensconced in their winter home, which was a full three weeks earlier than he had been able to ready it in the past. The snows arrived earlier that year as well, and when a knock came to their door one morning, during a sudden storm, Merian left bed reluctantly to open it for the stranded traveler who greeted him.

“I have lost a wheel,” the man said, as snow blew over the threshold and into the house.

While in the past he would barely have opened the door, let alone offered his assistance, his sense of peace made Merian eager to help, and he went off with the stranger in the snow to see if they could repair the carriage before the storm grew too foul.

It was as he walked home with the stranger and his team, after helping to right the overturned coach but not repair the wheel, which needed the attention of a smith, that he saw smoke from a fire not his own, which looked as if it rose from a built-up chimney instead of the bare ground of the forest. He thought then that he no longer lived at the edge of oblivion but had pushed its claim from his doorstep. He also envisioned how much easier the road would be to travel than when he walked it the first time, as parts of it were now graded. He thought then for the first time he might be able to keep his vow of the first year and return to Virginia someday soon for a visit.

He gave these things reign over his imagination as the dual aches of nostalgia and guilt seized him. One for the first family he had known and now missed, and the other for the wife to whom he owed his presence and loyalty.

As they waited out the storm in his house, he asked the stranger where he was headed and where he was coming from. The man answered only in half riddles but told him the trip had gone well so far, as the roads had been without hostility. When the storm let up several hours later, Merian continued to question the traveler, as they went into the village and even still as the smith turned the wheel on his lathe to realign the warped rim. When he finally escorted the man back to his carriage, he still had only a dim notion of who he was but reasoned that was the way it would remain.

Riding home in the snow-shadowed forest he looked around himself to ensure that no one else was on the road who might see his tortured thought. Instead of going into the house directly when he arrived even with his door, he went on a bit farther into the night, as if testing the road’s disposition toward him.

The stranger on their ride through the dark woods had inspired in him a feeling of great dread, as well as hope, that manifested itself now in the brooding trip he took back and forth along the road, thinking of his previous existence. “There is a great change coming to these precincts,” the man had preached, as they searched for the carriage in the darkness. “It will not make itself visible for years yet, but prepare thyself, for when it does it will be as if a hood has been lifted off the eyes of the world.”

“What hood is that?” asked Merian.

“It is the great darkness that prevents men from seeing the natural state of us all is in eclipse and shadow, and we had better not ask too much how such a life came to exist, but why any did. That is the hood that the preachers and politicians use to fool us ordinary folk. They tell you they have the postal address to Providence, but I tell you that you and I have a channel to the same divinity as the Bishop of Canterbury or the baby Christ, and you do not need permission for access. What they want is to assume your agency in this, the progress of your own salvation, and add it to the number of other souls they have hoodwinked, until they have amassed an authority to rival that of Lord John himself. No, brother, we must all be self-governed on this journey and keep any who wants it from getting control of this vessel, like some popish Argonaut, which he would then steer only toward his own destination and neither yours nor mine nor God’s.”

Merian went silent to hear this blasphemy and struggled to get the iron fastened around the stranger’s wheel. “What kind of preacher are you?” Merian asked at last, standing up. “Every other one of you I ever heard said the only plan for any of us is already mapped out by God.”

“No preacher at all but a poor pilgrim.”

He asked nothing else to be explained that night.

When he turned to leave, the man pressed a small coin of solid gold into his hand, which had embossed upon it a seal he had never seen before. “Now, there – there is something with materiality,” the man said in a conspiratorial whisper, though there was no one else on the road. “Remember our conversation, brother, and mark it when it comes around to you again.”

In his heart, which was superstitious and had not thrown off all the old tales he had learned in his boyhood, Merian began to tremble and look around himself as he paced the greedy road.

If it is oblivion that is our state, what indeed keeps anything from disappearing just as easily? he asked himself. This in its turn caused a great sadness to visit him that night, as he thought on things he had not visited in a very long time, and that indeed he thought perhaps best now forgotten.

When he returned to the house, Sanne sat up in bed waiting and asked why it had taken him so long.

“The wheel was worse off than I suspected,” he said.

“I see. And the traveler?”

“He is back on his way, but he was a strange one.”

“How so?”

“He was all talk of signs and claimed he had found a new way of measuring time’s progress.”

“You know what kind of talk all that is, don’t you?”

Merian was not pious, as his wife was, but thought he knew what she made of it all. He was happy, though, to have the talk turn in a different direction than the pathways of his worries. “Now Sanne, he was just somebody who was stranded and needed help.”

“This road is tarnished by all sorts,” she said sternly. “Who knows what all we’re likely to see out here before the end of it all?”

When he went out for wood that winter he found he had fallen into the habit of staring down the road whenever he happened to cross it, appraising its straightness and thinking how it went all the way back to Virginia in one form or other. He could not help but daydream of the other terminus. It was his current end, though, that always found and reclaimed him before he ever gathered the nerve to set back out toward the other.

As the spring came, and the ice thawed from the lake, he began to prepare his fields. On one of those mornings when thrush song was loud enough to cover the horrendous creak of melting ice, he looked out to the road and saw a new figure headed directly toward him. He kept at his work until the stranger stood in front of him. When he looked up from the shadow that covered the ground, he saw it was one he knew from long years before.

The two men clasped like kinsmen, and Merian invited the new arrival into the house, where his wife prepared for them a meal. When they had finished eating the two old friends began to reminisce and tell each other of former times and still other friends not forgotten.

As they grew comfortable, Merian had his friend, Chiron, wait while he went out of the house and into the root cellar. He returned with a jar of corn whiskey, which he had made in the tin tub he bought at the end of the previous season, and handed the jar to his guest.

“A drink,” was all the new arrival said as the hot liquid burned its way down his throat.

“It is the first batch,” Merian said, “but I could not imagine a better occasion for it. Tell me, what has brought you all this way?”

“Same as what brought you,” replied Chiron, who had a reputation as a seer back where they came from.

“How far you going?”

“I do not know.”

“You could stay on awhile.”

It was settled as simply as that, even after so long a separation, as each of them knew it was what he owed to the other man as a tithe to their shared past and common fate.

When Sanne asked about their relationship, Merian answered that they were cousins and did not elaborate on how.

They did not speak, however, about everyone they knew from the past, being content to enjoy each other’s company, and silence, and the occasional jar of corn whiskey. When Merian did ask once after one of their mutual acquaintances who had gone unmentioned, Chiron invoked the unspoken rule that had governed all of their discussions about the past until then. “Things always getting separated from their roots,” he said. “When a man grows up in one place and leaves, he goes off part of the original and part of something new. The original don’t always acknowledge the little offshoots, and all of them don’t always acknowledge the master copy, because they need to get on with being separate and new and sometimes so different it don’t make sense to talk about them at all anymore, other than gossip.”

In the mornings the two men went out into the fields and worked until midday, then returned home together, where they shared supper. The new man acknowledged this abundance of hospitality by working as hard in the sowing of Merian’s fields as he would have if they were his own. One morning, though, late in his visit, when the crows were in full commotion, he paused to read his friend’s fortune in their pattern, for he was learned and well-practiced in auspicating from the flight of birds. “You will profit twice more,” was all he said, as he stood from the place where he had sat to concentrate. Merian took the words as a mysterious gift to ponder and hope for, but he did not ask for further explanation, as he knew that was not how such things operated.

The arrangement continued well between them until late in the spring, when Chiron began to show signs of restlessness. As they worked outside one day, Merian asked him whether he wouldn’t consider staying on longer.

“There is a nice spot over that way where you could put up a house of your own.”

“I appreciate it, but I think it best to keep to the road a little longer,” Chiron replied, without looking up from his work.

“Well, it is there if you decide you want it,” Merian said, returning to his own work, as he was not one to argue with a grown man what his own best interest was.

With Chiron that year he had already planted twice as many acres as the season before and hoped to improve on that by yet a few lots more. Without his friend, Merian knew when harvest came there would only be him and Sanne to work the land, so he stopped his ambitions there where his hand might reach by its own power alone.

His mind, though, did not stop dreaming of increasing his till, and he began to experiment with a small batch of rice seed he bought from the dry-goods merchant, who claimed it had made men rich throughout the Caribbean. Chiron nodded when he saw them, and helped Merian to set up the patch, as he had some memory of the way the stuff was cultivated.

By early July, however, the plants were dry and yellow with no hope of growing further, even with Chiron’s nursing. Merian knew then the seeds were bad, and cursed the merchant for selling him them, swearing that would be the last time he did business with the so-called chandler.

“He has robbed me of my time and labor from two seasons,” he cursed, when he realized the plants were hopeless. “The first I spent saving to buy his rubbish and the second I spent trying to get them to grow.”

Sanne tried to console him. “It is no guarantee that a thing will grow only because it was planted.”

“There’s no chance of it at all if the thing is infernal,” Merian countered gloomily. He spent then long hours that night thinking of ways to recoup from the unreliable merchant, if not to cheat him of something as precious.

By morning his anger had departed and he could admit to himself that if nothing else was lost it would still be a better year than the one before. He devoted more time toward convincing Chiron to stay on, though, telling him that there was little to nothing in the country beyond them.

“Good,” he was answered, “because that’s what I aim to find. I’ve spent about enough days working and getting nowhere to know that nothing is a fine place for a man with a certain kind of head to be.”

“What kind is that?”

Chiron did not answer the question, saying only, “I’m going to go over there and think about all me and you and the Virginia folk been through and see if it doesn’t mean something more than that, like bird patterns against the sky.”

“What good can it mean to be bonded or else a hermit, with nothing but rags keeping him from the harm of cold and heat?” Merian asked.

“All of that is just passing,” Chiron said, in the old country way, and it was not his own way of reasoning but Merian could not argue against it.

When the crop was weeded, Chiron came and told him he was leaving, and did not care to be reminded that the caravans westward did not depart for several weeks still.

“Where I am headed I can’t imagine much caravanning.”

Merian paid him his wages with silver and added to it the coin that had been pressed on him many months earlier by the stranger he met that winter. He found all again beside the hearthstone next morning and nothing else gone from the storeroom but a little food and the bearskin.

So he had two visits that year and both of them religious in their own way. Nor would they be the last visits either, from seers, strangers, or holy men on the property. Nor were such the only ones to come to the house in those early years.

six

In the round heat of the summer months Sanne found herself beginning to grow heavy, and Merian realized there would be another mouth, and in time other hands, on the land. In optimism he began to expand the house, which he had first built in the old African style with a square foundation of twelve on either side. To this initial square he added a second, first placing in the foundation certain herbs said to be propitious and other provisions.

After laying the groundwork himself, he saddled Ruth Potter for the trip into town, intent on hiring someone to help with raising the walls. On the trip that year he noticed the village center seemed to be growing steadily outward. Where stands of wild trees stood before were now farms and storehouses, some of which, though newer and still modest, were already larger than his own. In all, things had changed so much over the previous year that Ruth Potter barely recognized her way, either to the general store or to Content’s inn, and offered up resistance as being in a strange land when they entered the town center.

“Still riding that mule?” Content asked, when Merian stopped by the tavern for his customary drink.

“She ain’t no worse off for it.”

“Seems like you’re doing well enough to get yourself a horse.”

“Next you’ll be trying to sell me on a carriage and livery.”

“It would be an improvement over that mule.”

“We can’t all be such country dandies as you, Content.”

“Can’t all get about on mules, either.”

“Do you know where I can find a man to hire? I need to make some improvements to the farm.”

“What is it you need?”

“Add a room.”

“Now that is fancy.”

“I can’t help it.”

When Merian told his friend the reason for the addition, Content nodded and refilled his glass, then called to Dorthea to share in the good news.

They drank a toast to Sanne, after which Merian followed his friend’s directions to a new tavern on the other side of the square, where the small road crew was said to take lunch.

When he walked in, he found the crew was nothing more than two brothers who had hired themselves out for the summer, being without land of their own.

“Would you like another job?” he asked them.

They answered that they were disinclined to work at all after their present job, work not being their preferred vocation.

“What is it you would rather be doing?” he asked.

“Just about anything,” the elder brother answered. “Work is not for us.”

“Then why did you take this job?”

“To eat,” the younger brother replied.

“You will still have to eat when you’re done.”

“But this one will feed us until the end of summer.”

He did not press beyond this, and when he left he did not berate them as hostile, for he could see they were short of wits. He but hoped his own children would not turn out so.

With Sanne growing heavier each day, he spent the rest of the summer as he had his first on the property, in grueling solitary work that lasted from first until final light. Mornings he woke and tended his fields; then, in the evening, began construction on the new building and cellar. As the warm days grew shorter, he began to despair he would not finish the task before the weather came down from the mountains.

By the first days of September it was nearly time to harvest his crops as well. The maize was as high as the archer’s bow over Old Cape, and the tobacco leaves were two full hand spans across. Sanne’s garden was also prospering, and they looked forward to reaping as much as in the last three years combined. He went to sleep nights that month thinking of his cellars bursting with the year’s increase, and his pockets overladen with money from the produce he would sell at market. How he would enjoy these rewards from his labors and reinvest the surplus well back in his fields.

The land, being free and fickle, though, conspired with the weather in mid-month against him, when a violent storm began to lash the house as they slept in the coolness of the old building. Merian awoke to the full force of the gale whipping the boards and joints of his house and the violent rains already under his door.

When Sanne woke she found her husband standing in the doorway cradling his head in his hands. “Are you going to stand and hide while it takes the whole season away from us?” she asked, as he stared out at the storm.

With an enormous effort he gathered himself and marched out into the rain to begin harvesting maize from the soggy plants, trailing a muddy sack behind his bent form as he went. In the house Sanne lit her oven, and when each sack was filled he would haul it to the house and unload it near the door. She then took and arranged the ears in stacks for drying in the heat of the kitchen, as he went back into the storm for the rest of their production.

They worked at it through the darkness, but in the morning the rains still slashed down in an onslaught that flooded the fields. Merian, exhausted, threw himself onto the earthen floor in defeat at about ten that morning, unable to work at all anymore.

“Are you quitting?” Sanne asked, as his weight oozed agreeably into the mud in front of the door.

“Let the devil have it,” he said, refusing to rise again.

“I did not know I had married a lazy man,” she told him, taking the sack up where he had left it, and going off into the rain to save what was left of their harvest. Seeing her go to fulfill the contract that he himself could not caused him an abiding sense of shame. He nursed this emotion but did not move from the floor.

It was only when he saw her pregnant form struggle to bring the first full sack to the door that he rose and went off to help.

“I am just a man, Sanne,” he said, taking the sack over his raw shoulders and setting out again. She looked at him then and was filled with pity. Her children, she swore, as he dragged the sack behind them in the feeble morning light and she looked at his mud-streaked face and the tatters of his shirt clinging to his frame, would be greater than this.

When they reached the door of the hut, she stopped short at the threshold, sensing disaster. “You don’t smell that?” she shrieked when she figured out what it was.

He did then, but he had not before. The maize that was outermost in the pile had taken on too much fire and was charred down half its length. Both looked at the burnt husk of their efforts, not speaking either to the other.

“We’ll have to throw it all out,” she lamented finally.

“It might still be good for feed,” he told her.

“Not even the pigs,” she answered.

“We will try and see.”

Nor was that the end of the disaster. The rains went on another five days, and when they were done, he was left with little else besides his despair. When he took what remained to market, he was paid a third for his labors that year of what he had the one before, and the merchant told him to be happy he was having that. “The markets are depressed for even prime crops,” he said, “and your own is nearly rotten.” Merian took what he was given and boiled with rage that he should have so little for his work and so little to say over his fate. But he had no other recourse.

He went on to the dry-goods shop, where he bought that year almost the same inventory as the one before, adding to it the nails he would need to finish work on his building, but there would be no new tub for liquor and no new shoes for himself.

He returned to his farm at the end of that day so woebegone he did not bother to unhitch Ruth Potter from the crude wagon she hauled. Sanne went out to the back of the house and performed this task for him, unloading the wagon as well, feeling the same pity for her husband she had the night he lost his crop but not afraid as she had been.

When he started the next day, however, Merian showed no sign of his defeat as he went to work finishing the outer part of the new building. As he sat on a beam, nailing roofing shingles to the top of the structure, he looked out over his property and possession and called to Sanne inside the house.

“Sanne, what is it I used to tell you I was building out here?’

“Utopia,” she said, heavily making her way to him to see exactly what it was he wanted.

“Well, I am still building it,” he said defiantly, “and no one is going to break me in that.”

“Stop your foolish talk,” she reprimanded him. “You’ll tempt God or else worse.”

He hammered away and said nothing more to his wife that day, but in his heart he was as intent as he had been that first day on the land. He nodded to her in the muggy summer light and drove another nail into the crossbeam.

The roof went up on the new building just before the first snows fell that year, but the structure itself sat empty as the root cellar beneath it. There were no extras that year and no need of the additional space. For the interior of the building he had run out of funds to continue construction. When Sanne’s waters broke, just after the turn of the new year, she left their shared bed nonetheless and went into the other house, where she had instructed Merian to build her a set of furniture of her own design. When she disappeared into the other dwelling, he was not permitted to go in, and neither could he go for help, there being no midwife and him being afraid to leave her alone for the time it would take to go to town for Dorthea.

Merian paced in the old house, opening the door from time to time to go roam around out-of-doors. From the other room he could hear an occasional groan that caused him to stand still wherever he was at the time. A great shock of fear would pass through him during those moments, heavy with the wailing agony that emanated from the other room. As the night wore on, the frequency and severity of her groans increased, until he found himself pressed with his back against the wall between the two rooms in paralysis. After another of these noises he knew he would not be able to bear it any longer and called in to her. “I’m going to go fetch Dorthea.”

From the other room Sanne screamed back at him. “Don’t you dare leave me out here in the middle of creation”—she added, “just because you’re scared of a birthing.”

Merian walked out of the house and all the way to the road with worry, before turning back to the house, trying to figure out what he was supposed to do, either leave her for help or stay there helplessly while she cried out in pain. Finally he made his way back to the other house and pushed at the door. It was fastened from the inside, and he was forced to shove his shoulder into it with his entire might until it budged but only the smallest bit. Through the crack he could barely make out her form but saw that she stood in the middle of the room, holding on to the halfborn violently.

He thought then, that this was how she escaped her prior marriage childless, by killing them off as they came into the world. He yelled at her to stop as he rammed his frame into the door again.

The rough-hewn door was swollen with dampness and cleaved to its position. Merian threw himself into it again with greater and greater force, until the wood began to creak and splinter. Still Sanne said nothing to him nor made any motion to let him into the room; rather, she continued on in her task and the sounds of pain she had emitted before.

Finally he rammed the door with his foot and succeeded in making it give way. He entered the dark room and rushed toward his wife, as his eyes adjusted to the lack of light. When he was upon her he saw that she held the newborn creature with all the gore of birth still attached. She looked up at him with an implacable face.

“He came first by the feet,” she said, telling him to get her a towel. “What is all the commotion you are keeping up?”

He said nothing, ashamed of his former suspicions.

She took the child then and moved sorely to her side, where she reached a basin of water and began to clean it. When she had finished, and he could distinguish the baby’s human shape, she held it out to him. He, for his own reasons, looked on the creature but did not move to receive it.

* * *

For days after the birth she stayed in the other room with the newly repaired door still barred and forbade him entrance. She sat then with her child and talked to him and sang to him the songs that had been sung to her when she was small, but for the father she gave little thought except when he came around to bring or retrieve something at the door.

In all the two of them, mother and son, were sequestered nearly a fortnight in the other house, and Merian began growing used to their absence. When they finally did emerge, he was at work mending the chicken coop and did not see them until he returned to the house later in the day, when he entered the room to find it hot as the oven could make instead of cool as he liked to keep it. Sanne sat in her chair by the little window cradling the boy and, when she saw her husband, held his son out to him. Merian looked at the child a second time but did not take him in his hands.

“Don’t you want to hold your boy, Jasper?” she asked. “What is the matter?”

He said nothing but went over to the fire to get his lunch, his hands trembling as he poured the soup he had prepared days earlier into a bowl.

“Well, have you thought about what you want to call him?” Sanne asked, as Merian took a bit of the watery broth and looked over at the child’s hovering eyes.

“I thought you might of named him already,” he answered her.

Sanne did not respond, as he sopped at the bowl with a piece of hard bread and stared straight ahead of himself. When he finished he stood up and went back to his work outside, leaving the two of them alone as they were used to being.

When he returned at dusk Sanne had baked new bread and prepared their dinner. Merian, still sulking, did not take his accustomed seat but avoided the common table.

Seeing that he was committed to his act, Sanne sat down and ate alone. Merian left her to the table and entertained himself with a pack of playing cards he had acquired. When the boy started to cry Merian cut his eyes between mother and infant, seemingly annoyed with both of them for disturbing his peace.